What will their level of agriculture and fishing be like? Because if they are more advanced (for lack of a better word) than OTL at the time, it may prompt a greater amount of settlement and exchange in response.

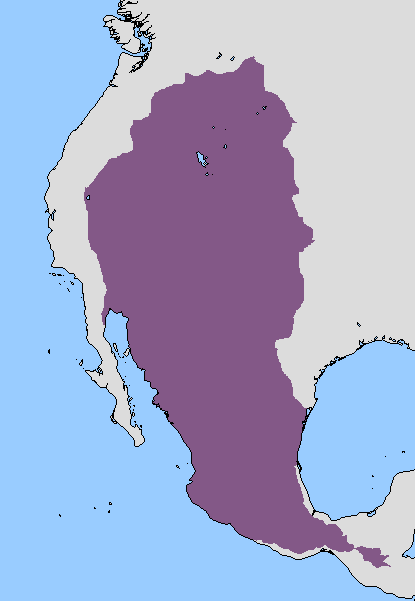

Newfoundland's the pertinent area here, I think, since it's where Leif and his Norse first landed and made contact with the natives. The nearest major population center to *Newfoundland ITTL as of ca. 1000 CE is hundreds of miles away in *Nova Scotia (which is nearer to the Northeast Columbian cultural area, which will probably start taking off between 800 and 900 CE). I imagine the *Nova Scotians have little compulsion to sail north, but they must make contact with the people living in *Newfoundland on occasion.

That said, the contact probably isn't frequent or particularly fruitful. Newfoundland has very poor soil, and its agriculture, even in modern times, has been more or less purely supplementary in nature. The fishing is good, but there likely aren't any major innovations in that craft which would have made it northward to Newfoundland at this date.

I do concede that the people the Norse make intermittent contact with here must by necessity be different from OTL, as the Beothuk probably would not have moved across the strait from Labrador as they did IOTL, and may well not exist as a distinct group at all. But whatever group lives there will not have anything more to entice the Norse to stay than the Beothuk did IOTL. The story in Labrador (Markland) is very similar, and Baffin Island (probably Helluland) is very sparsely-populated indeed.