Huehuecoyotl

Monthly Donor

Northern *New Mexico, ca. 10,500 BCE

The beast was tall and ungainly-looking - he wondered if perhaps its kind had been deer until stretched out by the hands of the creator. Atop a long neck sat a grossly large head, the beast’s dark, beady eyes turned away from the human as it browsed among the fresh shoots of a low-lying tree. Fat, padded feet, hard nails on the tips, mashed the rather less interesting grasses underfoot, a small tail flicking at the flies accompanying the creature.

Even in his father’s time, these long-deer had been common in the Lands of the Juniper, but increasingly their numbers dwindled, drawing away to the highlands of the great mountains and the distant south. The hunter considered it an omen of great fortune that an animal bearing so much good meat had wandered into his hunting grounds. Licking his lips and squinting against the light of the rising sun, he readied his atlatl – and let fly.

The crude spear sailed through the air, and here something changed. Perhaps the sunlight had worsened the hunter’s aim by a hair. Perhaps the long-deer’s eyes turned to a different leaf or shoot. Perhaps a slight twitch of the hand or an unnoticeable buffet of the air had altered the spear’s course. Whatever tiny alteration had taken place, the spear narrowly missed the animal.

The weapon crashed through the thickets past the heretofore-browsing long-deer, creating a great racket and spooking the animal. With a terrified bleat, it wheeled, charging off into the juniper forest, and was gone.

Smacking his forehead and cursing his stupidity, the hunter went to retrieve his spear, deciding that the elusive long-deer was not a lucky omen after all.

And so, a single animal, who in our own timeline would have perished at the spear’s point, escaped to the company of his fellows in the nearby highlands. The young male’s genes passed into the gene pool of this previously-dwindling species of North American camelid, affecting the population just enough within a few short generations to pass on his speed and hardiness to his progeny.

Hemiauchenia macrocephala survived by a hair, and the world would be changed forever.

A Camelid Odyssey

40 Million Years of Evolution

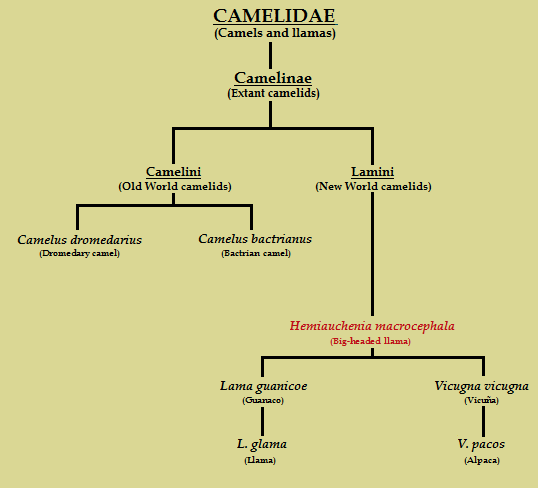

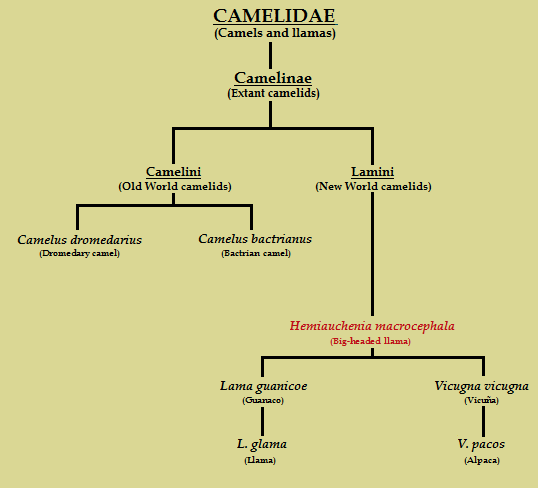

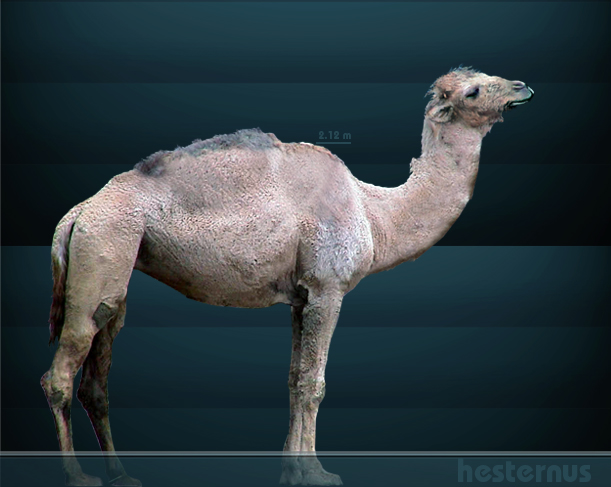

A family tree of the living members of the family Camelidae. Hemiauchenia macrocephala, which is extinct in our timeline, is placed on the tree in red above its probable descendants, today's South American camelids.

40 Million Years of Evolution

A family tree of the living members of the family Camelidae. Hemiauchenia macrocephala, which is extinct in our timeline, is placed on the tree in red above its probable descendants, today's South American camelids.

The camelid family is a remarkable group of animals. Belonging to the order Artiodactyla (that is, the even-toed ungulates), Camelidae is the sole surviving representative of the suborder Tylopoda. Though today its only relations are (very distantly) pigs, and ruminants like cattle and deer, the tylopods once bore a diversity of forms such as the anoplotheres and the somewhat less obscure oreodonts. All we have in our own timeline today to attest to this once-great diversity are the six extant species of camelids which represent this unique clade of hooved mammals.

Camelids are distinguished by their long necks and legs, their unique dentition (their canines and premolars are almost like tusks), and their lack of hooves - modern camelids all have padded feet with a pair of toenails (thus Tylopoda, 'padded feet'). Camelids by and large are found in arid environments of any temperature, from Andean mountains and deserts to the cold steppes of Central Asia. In the past, fossil camelids even thrived as far north as the Arctic Circle, proving the hardiness of this family and its adaptability to many different climates. The earliest known representative of Camelidae is the tiny, deer-like Protylopus, which lived in the Eocene, 45 million years ago. While Protylopus had four toes rather than two, and appears to have had hooves on its feet (unlike any living camelid), otherwise it already exemplifies the basic, camelid body plan.

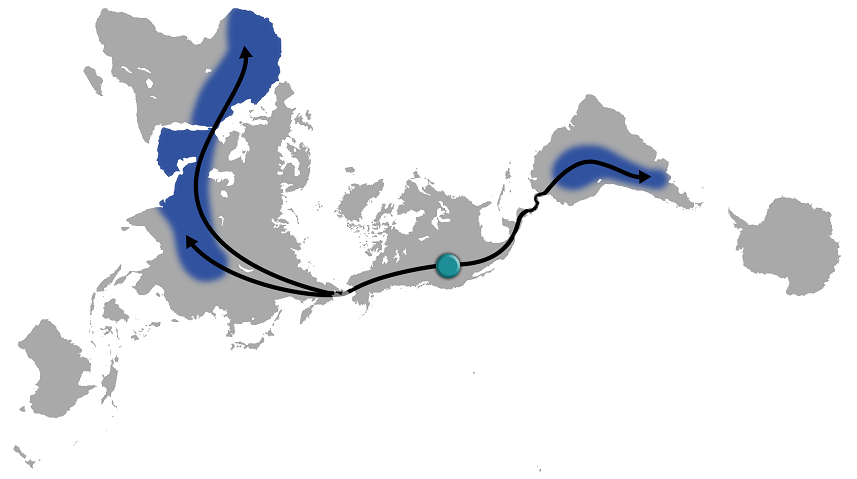

Protylopus petersoni

The camelids carried on in modest success, diversifying in form and occupying most of the large mammal browsing niches of North America, but never spreading outside of the continent. Nonetheless, from California to Tennessee and from Canada to Mexico, the camelids spread across the continent, and persisted through every epoch of the Cenozoic Era from the Eocene onward. The camelids would have their heyday during the Pliocene when North America and South America met at Panama for the first time since the age of the dinosaurs. This momentous event has been termed the Great American Interchange, and began around 3 million years ago. Large mammal species (and large birds in at least one case) migrated over the new land bridge, seeing the introduction of armadillos, ground sloths, and saber-toothed cats amongst others to North America, and the horse, elephant, tapir, and (most importantly to our purposes) camelids, to South America. At about the same time, the camel branch of the family crossed over into Eurasia for the first time via the Bering Land Bridge in Alaska, soon siring the lineages that would become today's dromedary and Bactrian camels.

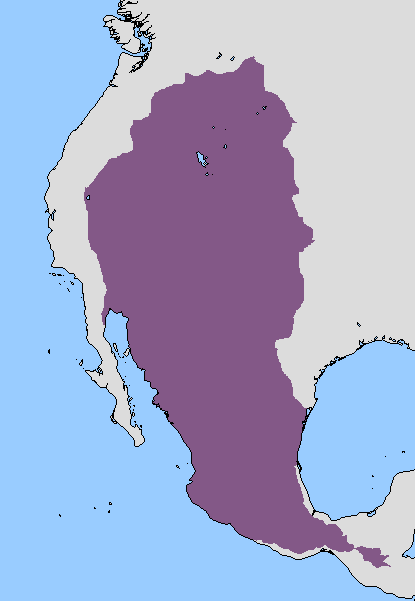

The dot in western North America represents the area in which the camelids originated.

It was only when the growing human diaspora invaded the continent in the last 30,000 years that their ongoing success was threatened - by the end of the last glaciation, the camelids of North America were very nearly extinct, soon to be relegated to the same fate as their oreodont and anoplothere cousins before them.

But perhaps, if a hunter had missed his target...

The Uurung

Hemiauchenia macrocephala, the Quintessential Columbian Camelid

From "The Uurung, A Natural History" by Addison Shorely, Oxford Press

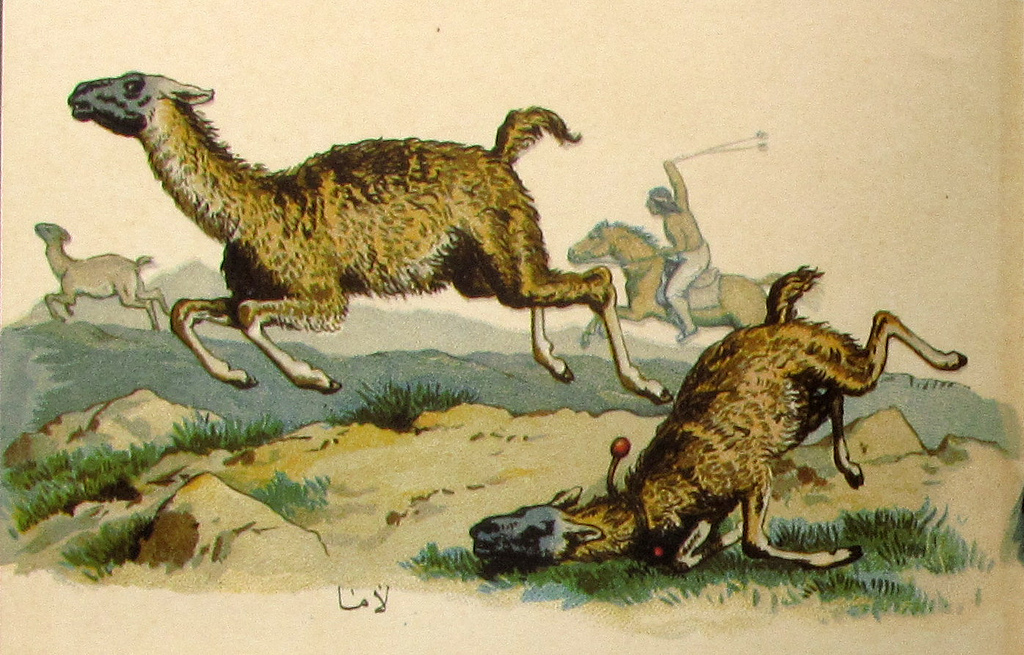

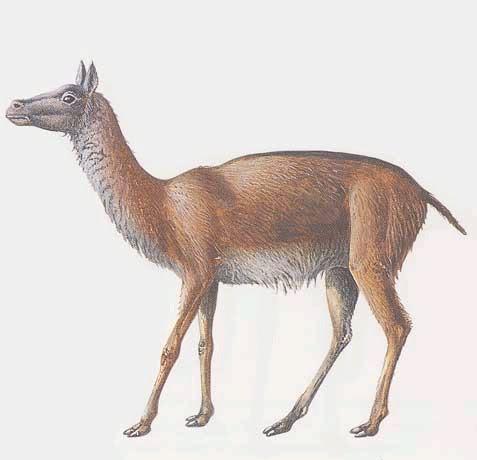

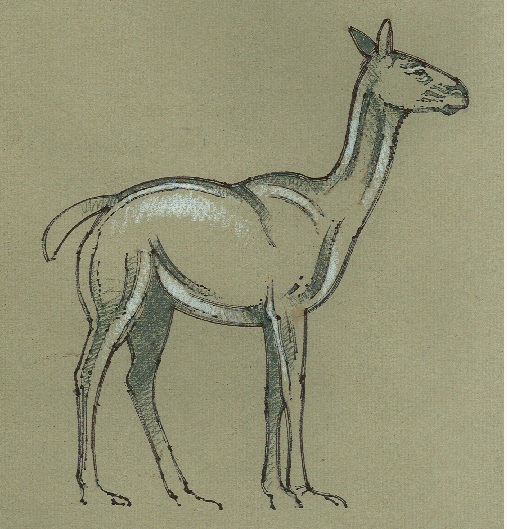

Hemiauchenia macrocephala in its wild form (compare with this image of the South American llama.)

Evolutionary History

Hemiauchenia macrocephala, the Quintessential Columbian Camelid

From "The Uurung, A Natural History" by Addison Shorely, Oxford Press

Hemiauchenia macrocephala in its wild form (compare with this image of the South American llama.)

Evolutionary History

Consider, for a moment, Hemiauchenia macrocephala, the taxon from which all modern Hesperidian [American][1] camelids are descended. It's hard to imagine Columbia [North America] without its teeming herds of domesticated uurung, but it could very easily have not been the case. Genetic evidence shows that the Columbian population of the genus passed through a dangerous genetic bottleneck about 12,500 years ago, and that there may have been as few as only a few hundred Hemiauchenia across the whole of that vast continent.

Just what rescued Hemiauchenia from the same fate that befell their cousin, Camelops, is unknown, as the same extinction event claimed almost all the megafauna of the continent at the end of the last Ice Age. It seems to have been a happy accident that this remarkable animal rebounded following this nadir, giving rise to the splendid variety of Columbian breeds we see today.

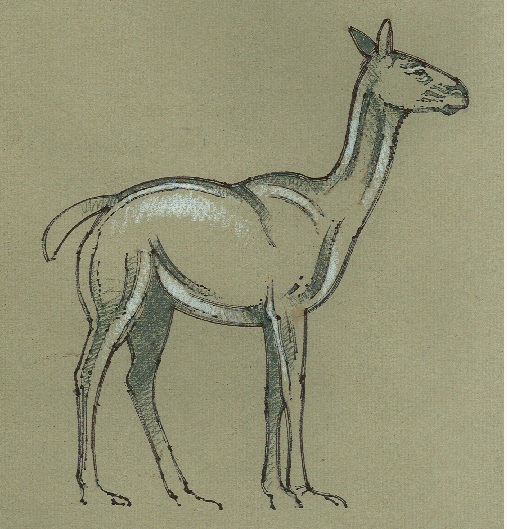

Camelops hesternus, the Columbian camel.

The genus, once it recovered, branched out rapidly, claiming the niches left behind by the extinct Columbian horses and bison[2]. They would soon make the jump across the desert to highland Isthmocolumbia [Meso- and Central America] and north along the length of the Alinta [Rocky] Mountains. From here the species diverged into two distinct wild subspecies: in Isthmocolumbia, the larger and more robust paixaay (H. m. macrocephala) arose, and in Petsiroò [a country in the *American Southwest], the smaller and more gracile breed traditionally called simply the uurung (H. m. petsiroensis) arose. As the name of the latter came to be used as a general term for all wild and feral members of Hemiauchenia, the Petsiroan variety has come to be instead called the true or Petsiroan uurung.

Description

Although the two subspecies of wild uurung share a number of differences in appearance, it is plain to see that they are both members of the same species. Both, like all camelids, have slender necks, long legs, and padded feet. As with all living lamines, the uurung are smaller than any Eurasian camels, but stand much taller than their Madeiran [South American] fellows. The wild male paixaay stands between 7.7 and 8.2 feet (2.34 - 2.50 meters) at the crown of its head (females are a head shorter), and even the comparatively smaller true uurung stands at between 6.5 and 7.1 feet. (1.98 - 2.16 meters). The former weighs in at an average of 670 lbs (304 kg), the latter a scant 510 lbs (231 kg).

Uurung have proportionately longer legs and larger heads than the Madeiran glama [the llama]. These strange proportions, like those of some African antelopes, allow both varieties of uurung to rear up onto their hind legs for a time to reach higher vegetation. In terms of dietary habits, uurung of both kinds have broad tastes in vegetation, owing to their far reach and well-varied dentition. These allow the animals to browse or graze as the situation demands. Uurung will prefer low-lying leaves and shoots, and abrasive grasses, if given the choice.

Uurung pelage resembles that of most other camelids in texture, providing soft, lanolin-free wool when grown to the right length and shorn. Paixaay fur is short, a signature of its adaptations to arid, semi-tropical savanna and desert, while the coats of true uurung are longer and shaggier. Paixaay fur ranges in color from a dark brown to a sandy, almost blond tan, while true uurungs come in brown, white, black, and any shade or combination thereof.

Unlike most other mammals, but as is the case with all camelids, uurung are induced ovulators, and their females do not experience heat or estrus every year. Almost without exception, the dam will give birth to a single cria [juvenile lamine], and will care for the young uurung for a year or two, when the juvenile reaches sexual maturity. A paixaay cria weighs around 56 lbs (25.4 kg) at birth, and that of a true uurung about 43 lbs (19.5 kg).

Uurung of all varieties are social animals. A group of paixaay will range anywhere from a single breeding pair up to a herd of over 20 animals, and true uurung herds can grow even larger. It is a rare occurrence to find an uurung of either type solitary. There is a strict pecking order within the uurung herd, with a single dominant male or breeding pair leading a number of females.

The social lifestyle, wide dietary range, and great adaptability of the camelids have seen their domestication in every continent on which they are found. In Columbia, it would see its domestication on two separate occasions.

Domestication

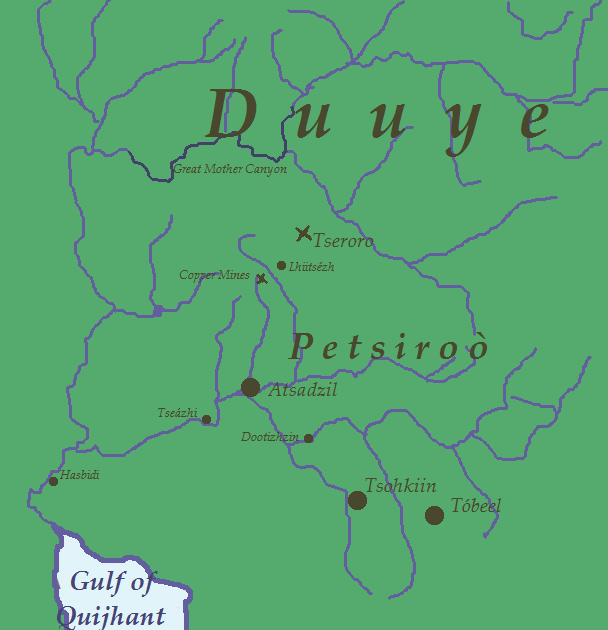

Since its survival by a hair's breadth at the close of the Pleistocene, the uurung's population had been slowly recovering, and by 5500 BCE had recovered to the levels of the Ice Age. Certainly human hunting of the animals had continued in this period, but it was only at this time that human societies began to take a serious interest in harvesting uurung meat.

Even fairly early in the Archaic Period, the wild true uurung (Hemiauchenia macrocephala petsiroensis) was prized for both its meat and its wool. Its fluffy pelage, while not yet as long or as thick as that of some of its domesticated descendants or its cousin the alpaca, was still useful to the people of the mountains and the foothills of the Alinta Mountains. Even in the lowlands and deserts, so hot during the day, the nights at certain times of year could be fairly cold. It was common practice, every two years or so, to drive herds of the animals into funnel-shaped corrals or mountain gorges, cut off their fur, and then set them free to be shorn again another day.

To a lesser extent, hunters sought out the preferred grazing places of the uurung, taking care to slaughter only as many as they needed to eat, and leaving the rest to keep the population growing. By 4000 BCE, semi-nomadic settlements had gained the habit of settling down near these areas of high uurung population density, and soon it became common practice to capture and tame crias to be raised close to home, ultimately to be slaughtered once they reached adulthood. Another 500 years or so passed until entire small herds were being tamed in this fashion, and true domestication of the uurung began in earnest.

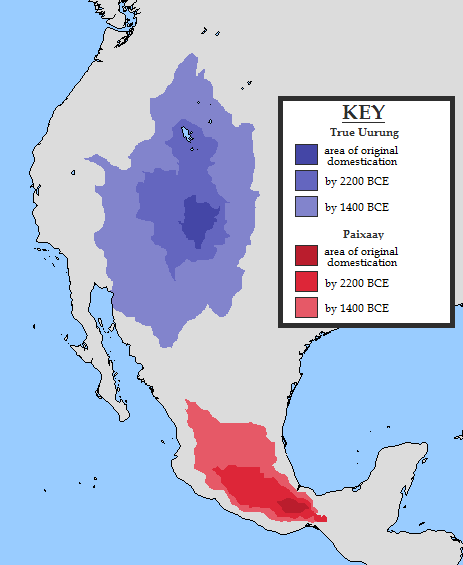

It is thus around 3500 BCE that the uurung was domesticated in Columbia for the first time, roughly in the same period as the camel in Arabia and the glama in Madeira. In the chilly mountains and foothills of the Duuye [Colorado Plateau], human settlements blossomed into a new period of growth as corrals of domesticated uurung sprung up all around the highlands. Due in part to the climate, which was hospitable for the animals, and due to the displacement of hunter-gatherer groups by the increasingly more populous uurung-herders, the range of uurung domestication spread rapidly up the length of the Alinta Mountains. By 2200 BCE, domesticated uurung were grazing near the shores of the Great Bitter Lake [Great Salt Lake], and by 1400 BCE had reached the Tuuwayan deserts[3] and the eastern end of the Nehwian Mountains [Sierra Nevada].

Interestingly enough, a fluke of ecology would give the first uurung-herders of Petsiroò an unexpected tag-along.

Part of the population growth of the uurung after the end of the Ice Age was owed to the extinction of almost all of the large carnivores that preyed on the uurung, such as the American lion and Smilodon. Although crias could still fall victim to surprise attacks from mountain lions, jaguars[4], or wolves, adult uurung no longer had any natural enemies. Most Columbian predators soon learned to avoid uurung herds, as an angered adult uurung is fully capable of killing even the most persistent of carnivores, owing to its considerable size.

Another large ungulate was found in the true uurung's range - the bighorn sheep, Ovis canadiensis canadiensis. Although not terribly flighty, and somewhat social animals, bighorn sheep (who share the same genus as the mouflon, the ancestor of the Eurasian sheep) have a fairly poorly-crystallized social hierarchy. Every mating season, competing males assert their dominance in their famous head-butting matches, but there is no such thing in a bighorn herd as a dominant male. If it weren't for the species' unique relationship with the uurung, this obstacle may very well have prevented the domestication of the sheep in Columbia.

While sporting a formidable rack of horns, the bighorn sheep is small enough not to enjoy the same lack of serious predators as the uurung. Bighorn lambs are especially vulnerable, but even adult rams aren't entirely immune. Bighorn sheep herds have since learned to stick near uurung herds, often intermingling directly during the wetter seasons when food is at its most plentiful. Thus, when domesticated herds of uurung began to make their home in or near human settlements, the sheep, who had begun to treat the camelids almost as leaders of the herd, followed after them.

By 1400 BCE, the Columbian sheep joined the uurung as the second large, mammalian domesticate of Columbia, and the third (or fourth) of Hesperidia.

Past the Tuuwaya Desert again, domestication came more slowly. The need to harvest uurung meat didn't arise as early as it did in Petsiroò, as Nuuyoo [Mexico in the Mesoamerican sense - that is, sans Yucatan] had a well-established set of crops which fed its population with general reliability. In fact, it was these crops that would ultimately lead to the independent domestication of the uurung in Nuuyoo, as the abundant new plant matter in the fields of the region proved appealing to juvenile paixaay. Although initially it was more common simply to kill the intrusive uurung for their meat, later on a process of capturing and taming similar to that in Petsiroò would catch on. By around 3000 BCE, a half of a millennium after the true uurung, the paixaay joined its cousin among the ranks of Columbian domesticates.

Domestication of the paixaay spread more slowly, but by 1400 BCE, it had spread into all but the most humid areas of Nuuyoo, and was expanding in the direction of the Tuuwaya. Here, as trade routes converged and the two breeds of uurung met, the future of Hemiauchenia and Columbian society would change forever...

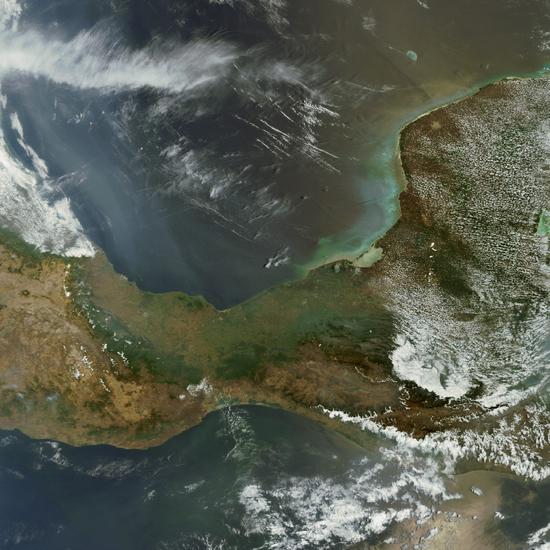

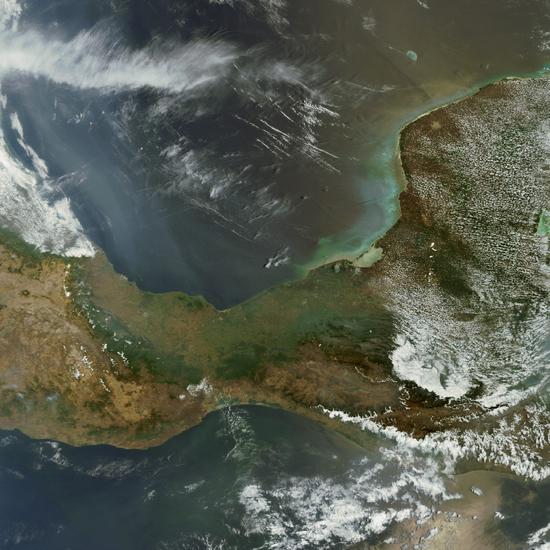

The spread of the twin breeds of domesticated uurung, as of 1400 BCE at the beginning of the Great Columbian Synthesis.

Lands of Bronze and Fire

An American Domestication Timeline

--------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] - Rather than being identified as a true pair of continents (e.g., "The Americas" or "America") ITTL, they can be grouped instead as Hesperidia, the lands of the Western Hemisphere. This is largely synonymous with the "New World".

[2] - By the time of European contact, the American bison will have gone the way of its big-horned, Ice Age cousins and be driven to extinction, displaced from its grazing lands by vast uurung herds. It's Eurasian cousin, the wisent, will survive it - but whether it survives to the present itself remains to be seen.

[3] - This is a slightly nuanced term. It refers collectively to the Sonoran, Chihuahan, and other north Mexican deserts, as well as any non-desertine areas which happen to fall between Oasis- and Mesoamerica. Tuuwaya will be very important later on.

[4] - Owing to the survival of the uurung (and a couple other megafauna species whom we will meet later), the jaguar enjoys a much larger range in western North America. The California condor will likewise enjoy better luck ITTL.

I don't want to rehash stuff which others have already written on extensively, or to busy myself with things hardly affected by the POD, so here's some "out-of-class" reading for you:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_Mesoamerica

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peopling_of_the_Americas

Neither of these should be significantly different ITTL

The First Cradle

The Formative Period in Naizaa

From "Two Cradles: New Revelations of the Origins of Civilization in Columbia" by Otis van Hoek, Nova Vizcaya University Press, 2006

The Formative Period in Naizaa

From "Two Cradles: New Revelations of the Origins of Civilization in Columbia" by Otis van Hoek, Nova Vizcaya University Press, 2006

Anthropologists have often opined that it is in areas of great climatic variation that complex cultures first develop, and the region of Naizaa would seem to lend this idea credence. A thin but mountainous strip of land separating the Atlantic and Panthalassic [Pacific] Oceans, the Isthmus of Naizaa bears a staggering number of microclimates amongst its misty mountains. Shaded valleys knock elbows with the Gulf coast's humid jungles, while the Panthalassic coast tends to be cooler and more arid. Highland plateaus and the trailing end of the Nava [Sierra Madre] ranges dominate much of the landscape, interrupted by the narrowest point of the Isthmus itself. Here, trade winds blow from the Gulf to the Panthalassic, spawning disastrous mountain-gap winds, with hurricane-like effects on the region. Despite the often unstable climate, it was here that Columbia would, for the first time, attain three monumental accomplishments - the development of agriculture, the domestication of large mammals, and the birth of civilizations.

It was not, however, in those mountains, but in the humid lowlands along the Gulf coast that the continent's first city would be born. First uncovered in 1961, the original name of the ancient city (settled perhaps around 1750 BCE) is long since lost. Now it bears a name from the language of the later Otopa - "Manaj Babil". Though today only the faded outlines of foundations and an earthen mound give any indication that Manaj Babil ever existed, decades of study will ensure that it will be forever remembered as the oldest city of the continent - at least until an older one emerges from the jungles to claim its lofty title. Despite its recent archaeological importance, the site is threatened by encroaching urban development, a symptom of the endemic obstacle presented by growing human populations to the study of Nuuyoo's ancient past.

A few middens on the perimeter of the site show that precious jade and chalcedony from the distant highlands of Qu'umark [Guatemala] were rare and popular commodities at Manaj Babil, hinting at the distant and complex trade relations which already were springing up throughout the region. This and the site's stone buildings show that Manaj Babil likely had a political elite, capable of organizing civic projects, and forming networks of trade. For better or for worse, social stratification was born. Here there were not yet any large, domesticated mammals (save for man's eternal companion, the dog), and though game such as deer and moco [turkey] must have made up a significant portion of the diet, analysis of preserved containers among the ruins shows that maize, beans, and squash made up the bulk of it.

In spite of its surely eternal importance to Columbian archaeology, Manaj Babil itself seems only to have been occupied for about a century or two before being abandoned, perhaps choked out by growing jungles or outcompeted by the first centres of the Otopa culture[1] growing further to the east.

For centuries imagined as one of two sisters from which all Columbian civilization arose, like some sort of latter-day Babylonia, the mythical role of the Otopa as a mother culture has since faded as the importance of Manaj Babil and other early sites came to light. Nonetheless, a great many cultural innovations passed on to later Isthmocolumbia (and of course elsewhere later on) were pioneered in the ancestral Otopa lowlands. Where no writing exists from Manaj Babil or other Archaic sites, when the central Otopa site at Oote Nanav[2] arose with the dawn of the Formative Period its walls almost immediately began to speak. This early Otopa script has yet to be deciphered in any meaningful way, but would seem to represent the point from which written language would be transmitted to later societies of the continent. Likewise, numerous artistic-devotional themes (the jaguar, the feathered serpent, etc.) can first be found carved into the walls of Oote Nanav's temples.

The site appears to first have been occupied by 1600 BCE, the first middens of pottery from the farming communities there forming most of the original layers of archaeological finds. Stingray barbs and conch shells are also common, owing to the site's closeness to the coast. The city grew quickly, and by 1500 BCE, when other Otopan cities were coming into their own throughout the Isthmus' lowlands, the site was dominated by pyramids and temples, as well as the domed Observatory on the acropolis. We mustn't be fooled by 17th-century imaginings of the ancient Otopa as peaceable astronomers, despite the detailed diagrams of the movement of the planets that they left behind in their observatories. As other Otopa centers sprung up in the surrounding region, conflict surely erupted at times over territory and resources - at least one site, south of Oote Nanav, seems to have been destroyed violently by fire.

As the early Otopa culture reached its florescence, the highlands southwest of Oote Nanav where maize was first mastered experienced the rise of their own complex societies. The uurung, which fared so poorly in Otopa lands, flourished here in the highlands and on the drier, Panthalassic side of the Isthmus. This country, since dubbed the Nivdavaya after the people who live there, thus was soon home to its own cities, sprouting up among the fertile valleys; by 1500 BCE, the first Nivdavay civilization was born.[3] Individual towns and cities occupied their own hills or valleys, supported by terraced farms and great paddocks of uurung, generally remaining independantly-minded and separate from one another politically. This aloofness and sense of individuality, some would allege, has remained a distinguishing feature of the Nivdavay all the way up to the present, but soon one town would gain primacy and promise an end to this first, greatly fragmented period in their history.

In a valley among the Nava peaks[4], the city of Tsung'oo, today the longest continuously-occupied city of Hesperidia, rose around 1460 BCE. Owing to its commanding position, central location, and fine farming land, Tsung'oo quickly grew to dominate the region, establishing vassalship over many of the smaller Nivdavay sites. Interaction between the Nivdavay and Otopa was frequent, and often violent. The population of the Nivdavaya tended to grow more quickly than that of the lowlands, probably owing to the plentiful meat harvested from the domesticated uurung of the highlands. Even as Otopa culture enjoyed its height in the early 15th Century BCE, sites near the foothills were being encroached upon by Nivdavay herders and warbands. By the time that Oote Nanav and the other major sites realized that they were being edged out, it was probably too late to tip the scales against the Nivdavay advance...

--------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] - A Mixe-Zoquean people; OTL's Mokaya, Olmec, or possibly both.

[2] - On the Coatzacoalcos, near the foothills of the Tuxtla mountains; near San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan.

[3] - The Nivdavay are none other than the Mixtecs.

[4] - The Valley of Oaxaca, to be exact.

A few more differences from the last time around - as well as a different and more logical order to these early updates. Any thoughts or comments so far?

Last edited: