Chapter Twenty

The Battle of Trevilian Station

From “The Battle of Trevilian Station” by Eppa H. Taylor

LSU 1987

“General Anderson vigorously disagreed with General McLaws decision to defend Trevilian Station. Three Union Corps would be on them in the morning (Couch, Smith and Von Steinwehr), with one more close behind (Reynolds). McLaws intended to stand at the Station with three divisions, or twelve brigades in total. McLaws had the seniority however, and Hood agreed to stand on the defensive. Anderson gathered his troops about him at Trevilian Station and sent an urgent message to General Longstreet…”

From “A Thunderbolt on the Battlefield – the Battles of Philip Kearny: Volume III” by Professor Kearny Bowes

MacArthur University Press 1962

“Kearny had attached himself to Couch’s Corps which advanced down the Virginia Central Railroad with Newton in front, and Casey behind. Kearny was closely co-ordinating with Baldy Smith who was advancing along the Charlottesville Road. Rodman’s division led with Slocum and Stoneman in column following down the road.

Von Steinwehr had also pressed on in Hood’s wake and was fortuitously nearby on the Green Spring Road, with the division of the now wary Julius Stahel in front, followed by Schimmelfennig and Devens columns. Stahel’s earlier experience at Hunter’s Landing meant that he was quick to form his men into line that morning at the first sound of gunfire…”

From “The Battle of Trevilian Station” by Eppa H. Taylor

LSU 1987

McLaws had deployed his division forward, with Semmes covering Charlottesville Road behind Poore’s Creek, Cobb and Kershaw astride the Railroad, and Barksdale on the right flank behind Hickory Creek.

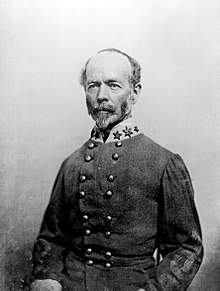

General Barksdale leads his troops to their new position

Hood had deployed his two brigades of Law and Wofford on either side of the Green Spring Road to welcome the IX Corps. Anderson had lent Hood Wright’s Brigade which Hood kept in reserve at the junction of the Charlottesville and Green Spring Roads.

Anderson had only three further brigades “in reserve” at Trevilian Station. He had deployed Mahone near the Poindexter Farm on the Fredericksburg Road to warn of any attempt to flank the station. Featherston’s Brigade was far in the rear at the crossroads of the Nunn’s Creek and Gordonsville Roads. “Needless to say General Anderson expected us to be flanked and the roads in our rear cut at anytime” (General Cadmus M. Wilcox)…

From “A Thunderbolt on the Battlefield – the Battles of Philip Kearny: Volume III” by Professor Kearny Bowes

MacArthur University Press 1962

“It was General John Newton who opened the battle that morning. He deployed his division with two brigades in front, and one in rear and went at Cobb and Kershaw’s brigades. General Kearny was concerned that General Couch had let Newton go in before Casey’s Division had come up. Couch reported that Casey had “a touch of the slows” that morning. He was not to be the only one…

Kearny had Couch pull Newton back and wait for Casey to deploy his brigades in two lines of two. When both divisions went in, Kearny was pleased with the results. Cobb and Kershaw were being pushed back. Casey complained that flanking fire (from Barksdale’s troops behind the stream) was decimating his flanking regiments. Kearny’s response was blunt “Stop complaining about their fire General and just damn well attack them”…

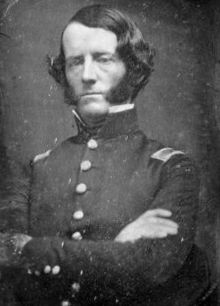

On the flank at Poore’s Creek the Rebel General Semmes was finding out how Quakers fight. Rodman had dismounted that morning at first light and crept down to the creek bank himself to establish that it was not much of an impediment to infantry. Afterwards he took his time to get all three of his brigades in line before launching an enveloping attack on Semmes. General William “Baldy” Smith, VI Corps commander, rode with him in the attack.

General Rodman thoroughly scouted his division's route

“I have never met a soldier with less thirst for military distinction, and with as little taste or predilection for military life yet he has risen by merit alone to the high rank he now holds… Patient, laborious, courageous, wholly devoted to his duties and influenced by deep religious convictions. It was a rare pleasure to have such a subordinate”.

Semmes brigade melted under the assault, and with his rout McLaws’ line was flanked. In a short time Rodman regrouped and hit Cobb’s flank as he tried to withdraw. The bulk of Cobb’s brigade would join Semmes at the rear of Rodman’s division on the way to a northern prison camp…

Kershaw and Barksdale were led from disaster by McLaws back towards the station…

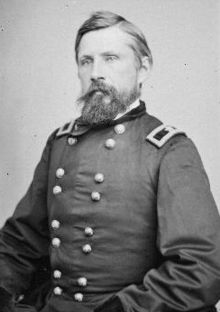

At little later that morning Stahel’s line ran into Hood’s. Von Steinwehr would permit Stahel’s troops to engage in a vigorous firefight, all be it at a “

respectful distance” while he brought up Schimmelfennig’s leading brigades on Stahel’s right. Von Steinwehr was always “

cool, collected and judicious” according to Kearny “

I need not be concerned for the 11th in his hands”…Eventually Hood was forced to pull his men back, to the other side of a clearing south of Trevilian Station. Into the gap Anderson placed Wright on the left, next to Hood’s brigades, and Armistead on the right…

Major General Adolph Wilhelm August Friedrich, Baron von Steinwehr

North of Trevilian Station McLaws had formed a new line of Kershaw, Barksdale and Wilcox. The new confederate position was in many ways two lines, parallel facing north west, with Armistead joining them in the middle as he faced southwest towards Stahel’s advance. Anderson likened the line to “

an stretched S or a lightening bolt”…

Kearny now had operational control of the three corps. The attack on McLaws section would consist of, from left to right Casey, Newton and Rodman, with Slocum in reserve. Stoneman had yet to bring up his division. Stahel prepared to assault Armistead…

From “The Battle of Trevilian Station” by Eppa H. Taylor

LSU 1987

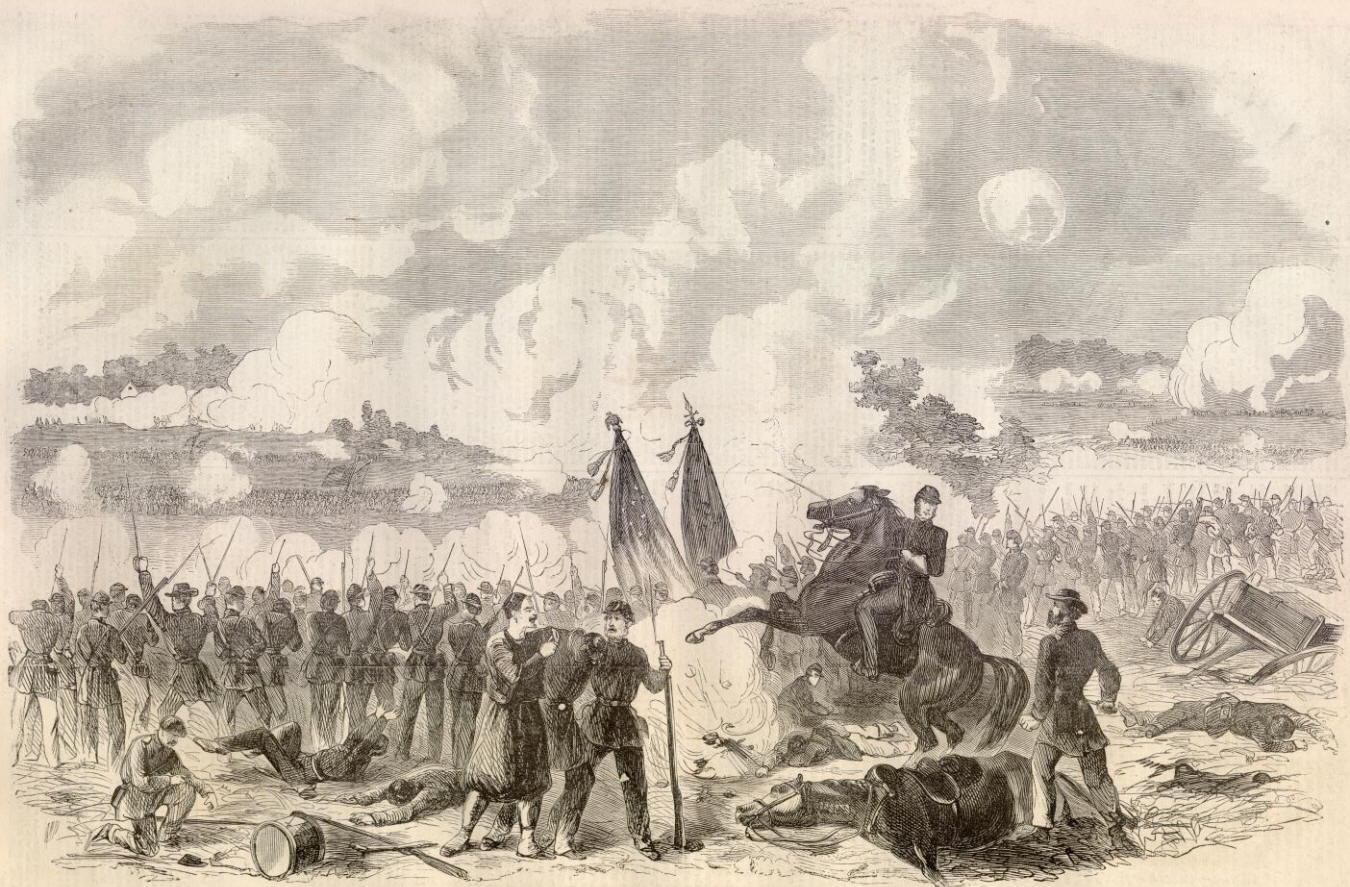

“It is unclear whether Kearny or Von Steinwehr stumbled in launching Stahel’s attack. It was to take place across 150 yards of open ground with the brigades of Wofford, Law and Kershaw on the flank... Stahel’s troops were cut down by the score. That was not enough for the aggressive Hood who sent Wofford and Law to the attack to ensure the route of Stahel’s brigades.

Stahel's Division are in over their heads in Hayfield Clearing

Rodman on the right flank of his own attack saw the collapse and warned his superior. Smith quickly grabbed Slocum’s leading brigades and lead them into the storm now raging before Trevilian Station. He was quickly joined by Von Steinwehr with Devens’ leading brigades, while Schimmelfennig assaulted Hood’s flank…

There were simply too many Union troops on the field. Kearny had a full division in reserve. Yet when Anderson summoned his remaining brigades only the distant Featherston marched to his relief. Mahone had himself been attacked on the Fredericksburg Road by more Union troops and had summoned Pryor to assist him. The ominous sound of gunfire could be heard in the lulls at Poindexter Farm. Anderson firmly believed another Union force has attempting to cut their line of retreat…

From “A Thunderbolt on the Battlefield – the Battles of Philip Kearny: Volume III” by Professor Kearny Bowes

MacArthur University Press 1962

“Kearny had deployed Pleasanton’s brigades of Averell and Gregg to raise hell in the rebel rear. It was working as Pleasanton held down two brigades sorely needed by McLaws and Anderson at the Station…”

From “The Battle of Trevilian Station” by Eppa H. Taylor

LSU 1987

“As Kershaw was driven back, Armistead’s flank was exposed to Rodman’s and Slocum’s attack. Anderson was pleading with McLaws to order a withdrawal. It was not forthcoming. Anderson sent word to Mahone – withdraw to Netherland Tavern. He then rode over to General Hood. Hood concurred, it was time to go…

Anderson gathered the artillery and sent it back down the road beyond Netherland Tavern and East Crossing, to the far side of a great clearing around the Gordonsville Road and the Railroad. It was to deploy in line, but only where it could retreat at speed.

Anderson then informed McLaws that he was pulling his troops out. Hood would cover the withdrawal by making another assault on the clearing before Trevilian Station, against the “Dutchmen” with his two brigades and Wright... An engagement of this kind was in direct breach of General Longstreet’s orders and could result in disaster for the corps. McLaws gave in…

From “A Thunderbolt on the Battlefield – the Battles of Philip Kearny: Volume III” by Professor Kearny Bowes

MacArthur University Press 1962

“Having thrown back the last desperate assault of Hood’s Division, General Kearny organised the pursuit of the fleeing rebels. Again Casey and Newton led, under Couch, with Rodman and Schimmelfennig in close support. Couch ran straight into the Rebel line of batteries. They did fearful execution…

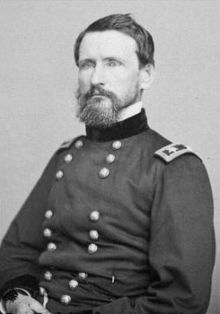

Couch's divisions stand in the face of heavy artillery fire

General Kearny turned to General Smith and Rodman “

Gentlemen lets us ride to that knoll so that we may draw fire from the boys of 4th Corps”. The three generals calmly sat on the knoll for 10 minutes while shot and shell descended on them. Two of Kearny’s staff and Rodman’s chief of staff were killed. Several mounted officers around the three were injured. Baldy Smith was grazed by a small fragment on his scalp. “

Why sir you will have a grand scar to show the ladies and it will have done your hairline no harm at all” Kearny joked. All three generals laughed.”

From “The Army of the Potomac in Their Own Words” edited by Horace Weldon

Greeley Publishing 1907

“I saw the Kearny and Baldy Smith and Rodman roaring with laughter while sat ahorse in the worst storm of bullet and shell on the field. I am convinced our generals are clean mad!” (Private Samuel M. Cooper)

From “The Battle of Trevilian Station” by Eppa H. Taylor

LSU 1987

“In the narrows between two creeks just north west of the Nunn’s Creek and Gordonsville Crossroads, McLaws blocked the Union advance with four brigades – Armistead, Wright, Featherston and Pryor, while Hood and Anderson marched of with the remaining six organised brigades (and the remains of Semmes and Cobb's brigades) and most of the artillery. McLaws insisted on commanding the rearguard. He intended to hold till nightfall and then withdraw….

Anderson waited expectantly the next morning, as Longstreet arrived after a dangerous overnight ride through contested country. Armistead marched in first, reporting that Kearny had maintained the assault throughout the night and eventually the tiny Confederate line had been routed. Pryor and Wright would also march in with the remains of their brigades, which were little enough. McLaws and Featherston did not. They had both been captured…”