Chapter Twenty Six

There's No South in Europe

Part I

From “The Rudderless Ship – The Confederate Diplomacy in the Civil War” by Aldous Morrow

Buffalo 1983

“Davis left foreign policy to others in government and, rather than developing an aggressive diplomatic effort, tended to expect events to accomplish diplomatic objectives. The President was committed to the notion that cotton would secure recognition and legitimacy from the powers of Europe. The men Davis selected as his successive secretaries of state and emissaries to Europe were chosen for political and personal reasons – not for their diplomatic potential. This was due, in part, to the belief that cotton and battle victories could accomplish the Confederate objectives with little help from Confederate diplomats…”

From “Great Britain and the American Civil War” 2 vols by Elijah Adams

New York 1925

“Even before the war, British Prime Minister Viscount Palmerston, urged a policy of neutrality. His international concerns were centered in Europe where he had to watch both Napoleon III’s ambitions in Europe and Bismarck’s rise in Germany. During the Civil War, British reactions to American events were shaped by past British policies and their own national interests, both strategically and economically. In the Western Hemisphere, as relations with the United States improved, Britain had become cautious about confronting the United States over issues in Central America. As a naval power, Britain had a long record of insisting that neutral nations abide by its blockades, a perspective that led from the earliest days of the war to de facto support for the Union blockade and frustration in the South…

Viscount Palmerston, British Prime Minister

Diplomatic observers were suspicious of British motives. The Russian Minister in Washington Eduard de Stoeckl noted, “The Cabinet of London is watching attentively the internal dissensions of the Union and awaits the result with an impatience which it has difficulty in disguising.” De Stoeckl advised his government that Britain would recognize the Confederate States at its earliest opportunity. Cassius Clay, the United States Minister in Russia, stated, “I saw at a glance where the feeling of England was. They hoped for our ruin! They are jealous of our power. They care neither for the South nor the North. They hate both”…

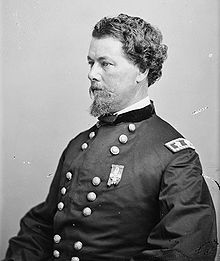

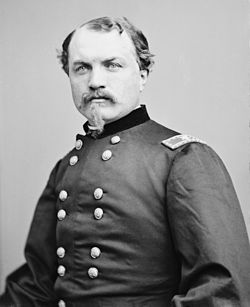

Eduard de Stoeckl and Cassius Clay

From “The Ghost of Wilberforce – British Anti-Slavery Sentiment and the Civil War” by Sir Reginald Elton-Duff

Pimlico 1923

“Slavery was repugnant to the moral sensibilities of most people in Britain. But up to the end of 1862, the immediate end of slavery was not an issue in the war and in fact, some Union states (Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland, Missouri, and Delaware) still allowed slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation, by making the end of slavery an objective of the war, had caused British intervention on the side of the South to be politically unappetizing…”

From “Great Britain and the American Civil War” 2 vols by Elijah Adams

New York 1925

“Earl Russell had given Mason no encouragement whatever, but after news of the Battle of the Rappahannock (reported as a Confederate victory over the Union Army of Virginia) reached London in early September, Palmerston agreed to a cabinet meeting at which Palmerston and Russell would ask approval of the mediation proposal. The revised reports, filling out Philip Kearny’s role in the battle, now portraying it as a stalemate caused Russell and Palmerston to conclude not to bring the plan before the cabinet...”

From “The Ghost of Wilberforce – British Anti-Slavery Sentiment and the Civil War” by Sir Reginald Elton-Duff

Pimlico 1923

“The British working class population, most notably the British cotton workers suffering the Lancashire Cotton Famine, remained consistently opposed to the Confederacy. A resolution of support was passed by the inhabitants of Manchester, and sent to Lincoln. His letter of reply, sent in January 1863, has become famous:

"... I know and deeply deplore the sufferings which the working people of Manchester and in all Europe are called to endure in this crisis. It has been often and studiously represented that the attempt to overthrow this Government which was built on the foundation of human rights, and to substitute for it one which should rest exclusively on the basis of slavery, was unlikely to obtain the favour of Europe. Through the action of disloyal citizens, the working people of Europe have been subjected to a severe trial for the purpose of forcing their sanction to that attempt. Under the circumstances I cannot but regard your decisive utterances on the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country. It is indeed an energetic and re-inspiring assurance of the inherent truth and of the ultimate and universal triumph of justice, humanity and freedom. I hail this interchange of sentiments, therefore, as an augury that, whatever else may happen, whatever misfortune may befall your country or my own, the peace and friendship which now exists between the two nations will be, as it shall be my desire to make them, perpetual"…

Lincoln became a hero amongst British working men with progressive views. His portrait, often alongside that of Garibaldi, adorned many parlour walls.”

From “The Rudderless Ship – The Confederate Diplomacy in the Civil War” by Aldous Morrow

Buffalo 1983

“Throughout the early years of the war, British foreign secretary Lord Russell and Napoleon III, and, to a lesser extent, British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, explored the risks and advantages of recognition of the Confederacy, or at least of offering a mediation. Recognition meant certain war with the United States, loss of American grain, loss of exports to the United States, loss of investments in American securities, potential loss of Canada and other North American colonies, higher taxes and a threat to the British merchant marine with little to gain in return. Many party leaders and the general public wanted no war with such high costs and meager benefits. Recognition was initially considered following the first reports of the Battle of the Rappahannock when the British government was preparing to mediate in the conflict, but the subsequent Union victories in the Rapidan Campaign and at the Battle of Ashland coupled with Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation caused the government to back away…

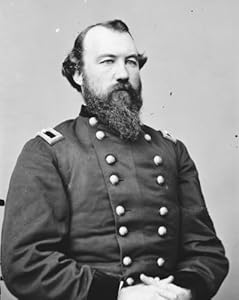

Earl Russell, British Foreign Secretary

In a further error during 1863, the Confederacy expelled all foreign consuls (all of them British or French diplomats) for advising their subjects to refuse to serve in combat against the U.S., further reducing the powers willingness to assist it.”

From “The Ghost of Wilberforce – British Anti-Slavery Sentiment and the Civil War” by Sir Reginald Elton-Duff

Pimlico 1923

“Both national governments [Britain and France] initially underestimated the power of the Emancipation Proclamation in bringing an end to slavery. Granted, the decree lacked the moral fibre demanded by the abolitionists and other anti-slavery activists. And it is true that the proclamation temporarily heightened the demand for intervention by appalling many British (and French) with its impetus to slave rebellions. But as Lincoln observed, and as the Duke of Argyll, John Bright, and Richard Cobden concurred in Parliament, the proclamation would inspire Union victory in the war and necessarily lead to the death of slavery. By early October 1862, the Morning Star in London declared that the Emancipation Proclamation marked "a gigantic stride in the paths of Christian and civilized progress . . . the great fact of the war—the turning point in the history of the American Commonwealth—an act only second in courage and probable results to the Declaration of Independence." Increasing numbers of workers joined in the praise, condemning slavery as a violation of freedom and hailing the president's recognition of human rights. To workers in London, Lincoln sent a note in early February 1863 declaring the war a test of "whether a government, established on the principles of human freedom, can be maintained against an effort to build one upon the exclusive foundation of human bondage”…

From “And The Doors Remained Closed” by Elise Van Der Horst

Berkeley 2007

“Like a thunderbolt from the heavens news of the execution of General David Hunter arrived in London. But while in New York, Washington and St. Louis the death of Hunter was the headline, in London it was the execution of 35 “unarmed negro sappers” (Morning Herald) that drove the story…

“It is inconceivable in any civilised society that unarmed workers can be put to death for the crime of ditching digging in service of the wrong side!” thundered Cobden at one anti-Confederacy rally in Manchester…

The Times, which had previously leaned towards the South was particularly scathing of the executions. “A people not worthy of a nation” ran one editorial. Public opinion, which had been divided between the Union and Confederacy until then, notably hardened against the Confederacy…”

From “Great Britain and the American Civil War” 2 vols by Elijah Adams

New York 1925

“Both Palmerston and Russell modified their position by recommending an armistice proposal rather than mediation. A cease-fire, they argued, might provide time for both antagonists to reconsider the wisdom of their policies; yet they also realized that an armistice without workable peace terms might lead only to a break in the action that allowed both sides to reload and fight anew. Secretary for War George Cornewall Lewis opposed any form of intervention, insisting that neither North nor South would consider reconciliation. What compromise could there be between Union restoration and Confederate independence? Furthermore Gladstone noted that the actions of the Confederate Government in promulgating Orders endorsing the execution of slaves and former slaves had put it “beyond of the pale” in the eyes of the majority of Britons of all classes…

Sir George Cornewall Lewis, Secretary of War

and prime mover in enforcing Britain's neutrality

Consequently, the British cabinet met for two days in September, vigorously debating the steps it should take in light of developments. Russell argued for intervention on a humanitarian basis, and Gladstone graphically described the horrible nature of the American war and called on England as a civilized nation to take steps to prevent its prolongation. Lewis had circulated a 15,000-word memorandum to his colleagues, warning that the interventionist powers had no viable peace terms and that an involvement would promote southern independence and guarantee war with the Union. However as the South had not yet established its claim to independence, England must remain neutral, and most importantly enforce that neutrality. Its laws were being ignored by Confederate agents. That contempt for the British rule of law must be firmly dealt with.

Lewis outlined a number of steps that the cabinet were to endorse:

1. Confederate agents in Britain should face the full power of the Foreign Enlistments Act which had been largely observed in the breach to date;

2. The Royal Navy should ensure Britain’s Caribbean Territories were not used by Blockade runners of any nationality; and

3. The neutrality of British North America should also be strictly observed and steps taken to expel the agents of foreign powers bent on disrespecting its borders and neutrality i.e. Confederate agents…

From the autumn of 1863 the British cabinet finally turned its back on any possibility of recognising the Confederacy as it was currently constituted…