Chapter 1: The Scottish King of England

From The Union of Crowns by Robert William Johnson

“It was in January of 1603 when Queen Elizabeth, first of her name, had first developed a bad cold and had been advised by her physicians and her chief astrologer, Dr. Dee to move from Whitehall to Richmond – one of her more warmer palaces, out of fear for her degrading health. Once there she seems to have refused all sorts of medicine, fearing that they would exacerbate her situation, and as the Earl of Northumberland informed King James VI in Scotland, her physicians were concluding among themselves that ‘if this continues, she must fall into a distemper, not a frenzy rather a period of dullness and lethargy.’

Queen Elizabeth I of England

The deaths on the 25th of February, of the Countess of Nottingham, the Queen’s closest female confidante served to compound her illness as grief took hold and while all of Scotland stirred in happy anticipation of her demise, the Queen merely sat down reclining on floor cushions refusing Robert Cecil’s instructions and pleas to take to her bed. ‘Little man.’ She had told him it seems. ‘The word must is not to be used on princesses.’ She was 69, plagued with fever, worn by worldly cares and frustrations and most assuredly dying – so that even she was forced to at least accede to the demands and pleas of her secretary. Then, in the hectic hours of 24th of March, 1603, as the Queen’s labored breaths slackened even further, worrying the Royal Council even further, Father Weston, a Catholic Priest who had been imprisoned at that time in the infamous Tower of London, noted how ‘a strange silence has descended upon London…….not a bell rang out, not a bugle sounded at all, frightening even the most patient of men.’ Her council was in attendance, and at frantic request of both the council and Cecil, the Queen finally accepted James VI as her successor as Monarch and Sovereign of England, after years of holding her mind about the topic.

Sir Robert Cecil.

At Richmond Palace, leaving at dawn that day, Sir Robert Carey was informed by the Royal Council that he was to move north to the Scottish Kingdom to inform James VI that he was now going to succeed his cousin as Monarch of England. Carey covered 162 miles before he slept that night at Doncaster. Next day further relays of horses, all carefully prepared in advance guaranteed that he covered another round of 136 miles along the ill kept and ill maintained track known as the Great Northern Road which connected London and Edinburgh. After another night at Widdrington in Northumberland, which was his own home, the saddle weary traveler marched north in the last leg of his exhausting yet fast and breakneck journey. He was in Edinburgh by the next evening and though the King was newly gone to bed, the messenger was hurriedly conveyed to the Royal Bedchamber after the Royal Seal of England was shown. There, said Carey, ‘I kneeled by him and saluted him by his title of England, Scotland, France and Ireland.’ In response to which James VI gave Carey his hand to kiss and bade him welcome to the northern kingdom.

James VI had dwelt upon the potential difficulty of the fact that his succession wouldn’t be clear cut neither would it be clean, and as a result the idea of invading the northern English marches to press his claim to the country was still a tangible fear and as a result, the Abbot of Holyrood the next day, was urgently dispatched to take the possession of Berwick, the gateway to the south as it was called back then, as his English councilors pressed the new King to make haste for plans for James VI’s transfer to London were complete.

Summoning those nobles who could be contacted in the time available, he placed the government in the hands of his Scottish council and confirmed the custody of his children to those already entrusted with them. Likewise, his heir, Prince Henry, was offered words of wisdom upon his new status as successor to the throne of England. ‘Let not this news make you proud or insolent,’ James informed the boy, ‘for a king’s son and heir was ye before, and no more are ye yet. The augmentation that is hereby like to fall unto you is but in cares and heavy burdens; be therefore merry but not insolent.’ Queen Anne, meanwhile, being pregnant, was to follow the king when convenient, though this would not be long, for she miscarried soon afterwards in the wake of a violent quarrel with the Earl of Mar’s mother, once again involving the custody of her eldest son – whereupon James finally relented and allowed the boy to be handed over to her at Holyrood House prior to their joining him in London.

James I and VI of England and Scotland.

Before his triumphant journey to England however, James VI had other things to attend to as well. On Sunday, the 3rd of April, he had to attend the High Kirk of St. Giles in Edinburgh to deliver a speech in which he asked his subjects to continue in ‘obedience to him and agreement amongst themselves’. There was a public promise too, that he would return to Scotland every three years, and a further suggestion that his subjects should take to heart upon his departure since had had already settled the matters of Kirk and Kingdom. All that remained after that address to his subjects was the plea to the council for monetary resources, since he barely had sufficient funds to get him past the old border, and a series of meetings with both English and Scottish officials and a mounting flood of suitors already seeking lavish rewards and promises forced the council’s hand in giving James VI the money he required. In the first category, Sir Thomas Lake, Cecil’s secretary, who was sent north to report the King’s thoughts as he became acquainted with English affairs and businesses, and the Dean of Canterbury who was hastily dispatched to ascertain James VI’s plans for the Church of England. To the second belonged a teeming self seeking thong of lower nobility. ‘There is much posting that way.’ Wrote John Chamberlain, a contemporary recorder of the public and private gossip of the time. ‘And many run thither of their own errand, as if it were nothing else but first come first served, or that preferment were a goal to be got by footmanship.’

In the event, James’s progress south might well have dazzled many a more phlegmatic mind than his, since it was one unbroken tale of rejoicing, praise and adulation. Entering Berwick on the 6th of April in the company of a throng of Border chieftains, he was greeted by the loudest salute of cannon fire in any soldier’s memory and presented with a purse of gold by the town’s Recorder. His arrival, after all, represented nothing less than the end of an era on the Anglo-Scottish border. In effect, a frontier which had been the source of bitter and continual dispute over nearly a millennia had been finally transformed by nothing more than an accident of birth, and no outcome of James’s kingship before or after would be of such long-term significance. That a King of Scotland, attended by the wardens of the Marches from both sides of the Border, should enter Berwick peacefully amid cries of approval was almost inconceivable – and yet it was now a reality for the onlookers whose forebears’ lives had been so disrupted and dominated by reprisal raids and outright warfare between both sides of the now former border, by all rights.

Widdrington Castle, Newcastle.

The new King continued his march south, not allowing the growing rain to dampen his spirits as many thought it would. He stopped in Northumberland at Sir Robert Carey’s Widdrington Castle, Newcastle on his way to York where he attended the local nobility and sermons and bishops as he continued his triumphant march to the south. On the 14th of April, James VI reached York by which point he was already extremely impressed by his new kingdom. The vast abundance of countryside, the richness of English land compared to Scotland’s rugged and barren territories and even the quaint little villages that he passed was much in contrast to Scotland, delighting the new English monarch.

On his way to London, James VI continued to entertain nobility and commoners of high rank with his entourage. Queen Elizabeth I had controlled the stem of giving away titles, such that of Knighthood with ever growing presence, yet James VI gave away knighthoods and titles of chivalry as he pleased with his entourage. During the entire reign of the Virgin Queen, only 878 knighthoods were given out to the country, whilst James VI’s entire march from the Scottish border to London saw around 906 knighthoods given out by the new King. It was a quite careless gifting of titles to people who did nothing but flatter their new monarch, however it did allow James VI to gain some amount of prestige and popularity among the high ranking commoners, who benefitted most from the knighthoods. James VI was most definitely giving away knighthoods because he was happy and flattered, of that there is no higher doubt, and however we cannot solely identify his reasons of giving away titles so frivolously as simply being flattered. New research into historical figures have analyzed and have come to believe that James VI was trying to imitate the cult of personality that Elizabeth I had built around herself by gaining some modicum of early popularity in his new kingdom.

Londoners dying of plague.

But what should have been the climax of the entire trip down to London, was met with an anti-climactic end. London, the capital of England and said to be the flower of the British Isles, was ridden with plague and the death toll in the city remained somewhere between 500 to 800 dropping dead every day. As a result, the entry of King James VI of Scotland, soon to be King James I of England and VI of Scotland, was delayed until the next season, spring, as the royal entourage hovered around London, accompanied by around 500 to 1000 citizens of the outskirts of London. The new Prince of Wales, Prince Henry was sent off to Norfolk so that he would not catch the potential plague that was indiscriminate in its attack against humanity, whether they be commoners, peasants, nobles or royalty.

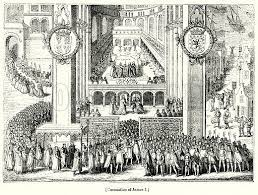

The Coronation of James I/VI

Even so, as the plague in London claimed the lives of around 30,000 Londoners, the coronation that occurred on the 25th of July, 1603, the feast of St. James the Great, was held in its normal grandeur and splendor, as citizens of London, many of whom had forgotten how a coronation looked like due to Elizabeth I’s long reign, came out in droves, despite the plague, to watch the coronation from the streets of the capital city.

By the time that James I/VI set out of London alongside his queen to go on a tour of the Southern Counties and Shires after the coronation period, the signs that the honeymoon period of James I/VI was coming to an end already beckoned the new monarch. The fact that James had already spent around 10,000 pounds on his journey to the south and had literally given away another 14,000 pounds in lavish gifts to nobles and oligarchs compounded with the fact that Elizabeth I’s massive funeral required 17,000 pounds to complete made the Royal Council and some members of the English Parliament grumble behind James I/VI’s back. The 400,000 pounds that stood in debt due to the previous Irish campaigns and attacks on the continent also compounded the financial situation of England. Robert Cecil wrote anxiously on the 18th of August, to the Earl of Shrewbury writing, ‘Our new sovereign, is going to spend nearly 100,000 pounds a year on his new mansion, which won’t even cost 50,000 in the worst of monetary days. Now think what the country feels and so much for that. The King must be reined in from these lavish spending.’

Some flaws of James I/VI’s characters also began to come up as the new King settled down in his new Kingdom. Some petitioners in Northampton who wanted to see their new king and petition him to act against some local corrupt clergymen who were exploiting the people, James I/VI had the surprised petitioners hauled up and rebuked for their manners, which was deemed to be little less than treason. James wasn’t inclined to play to the crowds either. Upon his entry to the capital after his southern tour, historian Thomas Wilson writes that the people started to miss the affability of their now dead queen, as the new King was much harder to speak with in the capital. James didn’t like to be looked on, that much was obvious by this point. Sir John Oglander also writes in his memoirs that, ‘Some people had come to the cathedral during our visit to see His Royal Person. Then, when His Majesty heard the news, he cried out in Scottish, ‘Gods Wounds! I will put down by breeches and they shall also see my arse!’”

Sir John Oglander

Yet if James’s improvidence and ineffability and disaffection to some of his Kingly duties were already emerging, other facets of his personality remained and continued to create a favorable first impression among many in the government and the country. The clergymen that the petitioners had asked to be investigated were in fact investigated and charged with corruption and exploitation and the facile and witty as well as oratory skills of James I/VI impressed many such as Sir Thomas Lake and Sir Roger Wilbraham. Even the critical and displeased eye of Sir Francis Bacon, who was displeased to have a Scottish man on the English throne, remained generally positive of the new King during his first meeting with the new King in Broxbourne. Foreign Ambassadors such as the Venetians, Tuscans and Neapolitans sang praises of James I/VI in their letters back to Venice, Florence and Naples.

Many liked the boyish attitude that James showed, seemingly a new breath of air for the formal and dreary courts of early modern Europe, however whilst this allowed the new king to create a new rapport among the people and nobility as well as the parliament, it also crossed the lines of decorum sometimes and embarrassed the king behind his back. For instance, when his favorite Sir Philip Herbert, whom he had created the Earl of Montgomery, married Lady Susan de Vere, who was also liked by the new King, in Whitehall in early 1604, the Scotsman was overcome with boyish high spirits and gave the new bride scores of gifts. He also wrote to Sir Dudley Carleton, ‘If Sir Philip won’t have her and was unmarried, I would keep her myself.’ It was a fatherly comment and an endearing one at that as it seems that Susan de Vere and James did have a father daughter like relationship with one another, but many doubted the light heartedness of the comment when heard through third and fourth hand sources, and began to spread rumors.

Susan Herbert nee De Vere, the Countess of Montgomery

Yet the adulation with which many Englishmen looked upon their new monarch, fake as it may have been on many occasions, perplexed the new king and definitely made James I/VI crave for more. In Scotland, the Lords and Nobles of the Highlands and the Clans could openly and frankly dispute words with their monarch and even sometimes usurp His power, however in England, courtly intrigues made such frankness impossible, and those who disagreed with their monarch spoke about it through twisting words, not speaking against their king directly. However James I/VI was also suspicious of his new realm and knew the inherent differences between the Scottish and English parliaments and knew that he would have to tread lightly between the two to make sure that he could consolidate his hold on both sides of his new realm. Sir Robert Cecil, the Secretary of the State of England under Elizabeth I was kept in his position and James I/VI very reluctantly under the influence of the new Earl of Montgomery and Earl of Shrewsbury, as well as Sir Thomas Lake, decided to take a small tutorship from his Secretary of State to understand the niceties of the English state that he would have to learn. James I/VI was definitely averse to the smaller niceties of kingly business, as his reluctance to meet commoners shows, however he was neither a fool nor a man who was out of the so called loop. As a result, together with Robert Cecil, Sir Thomas Lake and the two aforementioned earls, alongside other prominent members of English society, such as Sir Adam Newton (who despite being Scottish knew about English Laws quite extensively), and Sir Robert Carr (future Earl of Somerset), began to tutor the new English monarch on English Law and how to act in coordination between the Royal Prerogative and the Parliament of England, which placed subtle limits to royal power rather than the blunt limits placed in Scotland. [1]

Sir Adam Newton and Sir Robert Carr.

By and large, James I/VI would leave behind a mixed legacy, as many things he did were excellent and good for the nation and many things he did sparked controversy as well, however the tutorship that he took from the Englishmen undoubtedly aided in his endeavor of the fact that he is generally well regarded today in the British Isles.

***

[1] – Our Primary PoD. James I/VI was asked to be tutored in English law and niceties but was avoided otl, something that was taken up ittl, making James VI more aware of the situation in England around him rather than the somewhat clueless monarch that he was otl.

***

From The Union of Crowns by Robert William Johnson

“It was in January of 1603 when Queen Elizabeth, first of her name, had first developed a bad cold and had been advised by her physicians and her chief astrologer, Dr. Dee to move from Whitehall to Richmond – one of her more warmer palaces, out of fear for her degrading health. Once there she seems to have refused all sorts of medicine, fearing that they would exacerbate her situation, and as the Earl of Northumberland informed King James VI in Scotland, her physicians were concluding among themselves that ‘if this continues, she must fall into a distemper, not a frenzy rather a period of dullness and lethargy.’

Queen Elizabeth I of England

The deaths on the 25th of February, of the Countess of Nottingham, the Queen’s closest female confidante served to compound her illness as grief took hold and while all of Scotland stirred in happy anticipation of her demise, the Queen merely sat down reclining on floor cushions refusing Robert Cecil’s instructions and pleas to take to her bed. ‘Little man.’ She had told him it seems. ‘The word must is not to be used on princesses.’ She was 69, plagued with fever, worn by worldly cares and frustrations and most assuredly dying – so that even she was forced to at least accede to the demands and pleas of her secretary. Then, in the hectic hours of 24th of March, 1603, as the Queen’s labored breaths slackened even further, worrying the Royal Council even further, Father Weston, a Catholic Priest who had been imprisoned at that time in the infamous Tower of London, noted how ‘a strange silence has descended upon London…….not a bell rang out, not a bugle sounded at all, frightening even the most patient of men.’ Her council was in attendance, and at frantic request of both the council and Cecil, the Queen finally accepted James VI as her successor as Monarch and Sovereign of England, after years of holding her mind about the topic.

Sir Robert Cecil.

At Richmond Palace, leaving at dawn that day, Sir Robert Carey was informed by the Royal Council that he was to move north to the Scottish Kingdom to inform James VI that he was now going to succeed his cousin as Monarch of England. Carey covered 162 miles before he slept that night at Doncaster. Next day further relays of horses, all carefully prepared in advance guaranteed that he covered another round of 136 miles along the ill kept and ill maintained track known as the Great Northern Road which connected London and Edinburgh. After another night at Widdrington in Northumberland, which was his own home, the saddle weary traveler marched north in the last leg of his exhausting yet fast and breakneck journey. He was in Edinburgh by the next evening and though the King was newly gone to bed, the messenger was hurriedly conveyed to the Royal Bedchamber after the Royal Seal of England was shown. There, said Carey, ‘I kneeled by him and saluted him by his title of England, Scotland, France and Ireland.’ In response to which James VI gave Carey his hand to kiss and bade him welcome to the northern kingdom.

James VI had dwelt upon the potential difficulty of the fact that his succession wouldn’t be clear cut neither would it be clean, and as a result the idea of invading the northern English marches to press his claim to the country was still a tangible fear and as a result, the Abbot of Holyrood the next day, was urgently dispatched to take the possession of Berwick, the gateway to the south as it was called back then, as his English councilors pressed the new King to make haste for plans for James VI’s transfer to London were complete.

Summoning those nobles who could be contacted in the time available, he placed the government in the hands of his Scottish council and confirmed the custody of his children to those already entrusted with them. Likewise, his heir, Prince Henry, was offered words of wisdom upon his new status as successor to the throne of England. ‘Let not this news make you proud or insolent,’ James informed the boy, ‘for a king’s son and heir was ye before, and no more are ye yet. The augmentation that is hereby like to fall unto you is but in cares and heavy burdens; be therefore merry but not insolent.’ Queen Anne, meanwhile, being pregnant, was to follow the king when convenient, though this would not be long, for she miscarried soon afterwards in the wake of a violent quarrel with the Earl of Mar’s mother, once again involving the custody of her eldest son – whereupon James finally relented and allowed the boy to be handed over to her at Holyrood House prior to their joining him in London.

James I and VI of England and Scotland.

Before his triumphant journey to England however, James VI had other things to attend to as well. On Sunday, the 3rd of April, he had to attend the High Kirk of St. Giles in Edinburgh to deliver a speech in which he asked his subjects to continue in ‘obedience to him and agreement amongst themselves’. There was a public promise too, that he would return to Scotland every three years, and a further suggestion that his subjects should take to heart upon his departure since had had already settled the matters of Kirk and Kingdom. All that remained after that address to his subjects was the plea to the council for monetary resources, since he barely had sufficient funds to get him past the old border, and a series of meetings with both English and Scottish officials and a mounting flood of suitors already seeking lavish rewards and promises forced the council’s hand in giving James VI the money he required. In the first category, Sir Thomas Lake, Cecil’s secretary, who was sent north to report the King’s thoughts as he became acquainted with English affairs and businesses, and the Dean of Canterbury who was hastily dispatched to ascertain James VI’s plans for the Church of England. To the second belonged a teeming self seeking thong of lower nobility. ‘There is much posting that way.’ Wrote John Chamberlain, a contemporary recorder of the public and private gossip of the time. ‘And many run thither of their own errand, as if it were nothing else but first come first served, or that preferment were a goal to be got by footmanship.’

In the event, James’s progress south might well have dazzled many a more phlegmatic mind than his, since it was one unbroken tale of rejoicing, praise and adulation. Entering Berwick on the 6th of April in the company of a throng of Border chieftains, he was greeted by the loudest salute of cannon fire in any soldier’s memory and presented with a purse of gold by the town’s Recorder. His arrival, after all, represented nothing less than the end of an era on the Anglo-Scottish border. In effect, a frontier which had been the source of bitter and continual dispute over nearly a millennia had been finally transformed by nothing more than an accident of birth, and no outcome of James’s kingship before or after would be of such long-term significance. That a King of Scotland, attended by the wardens of the Marches from both sides of the Border, should enter Berwick peacefully amid cries of approval was almost inconceivable – and yet it was now a reality for the onlookers whose forebears’ lives had been so disrupted and dominated by reprisal raids and outright warfare between both sides of the now former border, by all rights.

Widdrington Castle, Newcastle.

The new King continued his march south, not allowing the growing rain to dampen his spirits as many thought it would. He stopped in Northumberland at Sir Robert Carey’s Widdrington Castle, Newcastle on his way to York where he attended the local nobility and sermons and bishops as he continued his triumphant march to the south. On the 14th of April, James VI reached York by which point he was already extremely impressed by his new kingdom. The vast abundance of countryside, the richness of English land compared to Scotland’s rugged and barren territories and even the quaint little villages that he passed was much in contrast to Scotland, delighting the new English monarch.

On his way to London, James VI continued to entertain nobility and commoners of high rank with his entourage. Queen Elizabeth I had controlled the stem of giving away titles, such that of Knighthood with ever growing presence, yet James VI gave away knighthoods and titles of chivalry as he pleased with his entourage. During the entire reign of the Virgin Queen, only 878 knighthoods were given out to the country, whilst James VI’s entire march from the Scottish border to London saw around 906 knighthoods given out by the new King. It was a quite careless gifting of titles to people who did nothing but flatter their new monarch, however it did allow James VI to gain some amount of prestige and popularity among the high ranking commoners, who benefitted most from the knighthoods. James VI was most definitely giving away knighthoods because he was happy and flattered, of that there is no higher doubt, and however we cannot solely identify his reasons of giving away titles so frivolously as simply being flattered. New research into historical figures have analyzed and have come to believe that James VI was trying to imitate the cult of personality that Elizabeth I had built around herself by gaining some modicum of early popularity in his new kingdom.

Londoners dying of plague.

But what should have been the climax of the entire trip down to London, was met with an anti-climactic end. London, the capital of England and said to be the flower of the British Isles, was ridden with plague and the death toll in the city remained somewhere between 500 to 800 dropping dead every day. As a result, the entry of King James VI of Scotland, soon to be King James I of England and VI of Scotland, was delayed until the next season, spring, as the royal entourage hovered around London, accompanied by around 500 to 1000 citizens of the outskirts of London. The new Prince of Wales, Prince Henry was sent off to Norfolk so that he would not catch the potential plague that was indiscriminate in its attack against humanity, whether they be commoners, peasants, nobles or royalty.

The Coronation of James I/VI

Even so, as the plague in London claimed the lives of around 30,000 Londoners, the coronation that occurred on the 25th of July, 1603, the feast of St. James the Great, was held in its normal grandeur and splendor, as citizens of London, many of whom had forgotten how a coronation looked like due to Elizabeth I’s long reign, came out in droves, despite the plague, to watch the coronation from the streets of the capital city.

By the time that James I/VI set out of London alongside his queen to go on a tour of the Southern Counties and Shires after the coronation period, the signs that the honeymoon period of James I/VI was coming to an end already beckoned the new monarch. The fact that James had already spent around 10,000 pounds on his journey to the south and had literally given away another 14,000 pounds in lavish gifts to nobles and oligarchs compounded with the fact that Elizabeth I’s massive funeral required 17,000 pounds to complete made the Royal Council and some members of the English Parliament grumble behind James I/VI’s back. The 400,000 pounds that stood in debt due to the previous Irish campaigns and attacks on the continent also compounded the financial situation of England. Robert Cecil wrote anxiously on the 18th of August, to the Earl of Shrewbury writing, ‘Our new sovereign, is going to spend nearly 100,000 pounds a year on his new mansion, which won’t even cost 50,000 in the worst of monetary days. Now think what the country feels and so much for that. The King must be reined in from these lavish spending.’

Some flaws of James I/VI’s characters also began to come up as the new King settled down in his new Kingdom. Some petitioners in Northampton who wanted to see their new king and petition him to act against some local corrupt clergymen who were exploiting the people, James I/VI had the surprised petitioners hauled up and rebuked for their manners, which was deemed to be little less than treason. James wasn’t inclined to play to the crowds either. Upon his entry to the capital after his southern tour, historian Thomas Wilson writes that the people started to miss the affability of their now dead queen, as the new King was much harder to speak with in the capital. James didn’t like to be looked on, that much was obvious by this point. Sir John Oglander also writes in his memoirs that, ‘Some people had come to the cathedral during our visit to see His Royal Person. Then, when His Majesty heard the news, he cried out in Scottish, ‘Gods Wounds! I will put down by breeches and they shall also see my arse!’”

Sir John Oglander

Yet if James’s improvidence and ineffability and disaffection to some of his Kingly duties were already emerging, other facets of his personality remained and continued to create a favorable first impression among many in the government and the country. The clergymen that the petitioners had asked to be investigated were in fact investigated and charged with corruption and exploitation and the facile and witty as well as oratory skills of James I/VI impressed many such as Sir Thomas Lake and Sir Roger Wilbraham. Even the critical and displeased eye of Sir Francis Bacon, who was displeased to have a Scottish man on the English throne, remained generally positive of the new King during his first meeting with the new King in Broxbourne. Foreign Ambassadors such as the Venetians, Tuscans and Neapolitans sang praises of James I/VI in their letters back to Venice, Florence and Naples.

Many liked the boyish attitude that James showed, seemingly a new breath of air for the formal and dreary courts of early modern Europe, however whilst this allowed the new king to create a new rapport among the people and nobility as well as the parliament, it also crossed the lines of decorum sometimes and embarrassed the king behind his back. For instance, when his favorite Sir Philip Herbert, whom he had created the Earl of Montgomery, married Lady Susan de Vere, who was also liked by the new King, in Whitehall in early 1604, the Scotsman was overcome with boyish high spirits and gave the new bride scores of gifts. He also wrote to Sir Dudley Carleton, ‘If Sir Philip won’t have her and was unmarried, I would keep her myself.’ It was a fatherly comment and an endearing one at that as it seems that Susan de Vere and James did have a father daughter like relationship with one another, but many doubted the light heartedness of the comment when heard through third and fourth hand sources, and began to spread rumors.

Susan Herbert nee De Vere, the Countess of Montgomery

Yet the adulation with which many Englishmen looked upon their new monarch, fake as it may have been on many occasions, perplexed the new king and definitely made James I/VI crave for more. In Scotland, the Lords and Nobles of the Highlands and the Clans could openly and frankly dispute words with their monarch and even sometimes usurp His power, however in England, courtly intrigues made such frankness impossible, and those who disagreed with their monarch spoke about it through twisting words, not speaking against their king directly. However James I/VI was also suspicious of his new realm and knew the inherent differences between the Scottish and English parliaments and knew that he would have to tread lightly between the two to make sure that he could consolidate his hold on both sides of his new realm. Sir Robert Cecil, the Secretary of the State of England under Elizabeth I was kept in his position and James I/VI very reluctantly under the influence of the new Earl of Montgomery and Earl of Shrewsbury, as well as Sir Thomas Lake, decided to take a small tutorship from his Secretary of State to understand the niceties of the English state that he would have to learn. James I/VI was definitely averse to the smaller niceties of kingly business, as his reluctance to meet commoners shows, however he was neither a fool nor a man who was out of the so called loop. As a result, together with Robert Cecil, Sir Thomas Lake and the two aforementioned earls, alongside other prominent members of English society, such as Sir Adam Newton (who despite being Scottish knew about English Laws quite extensively), and Sir Robert Carr (future Earl of Somerset), began to tutor the new English monarch on English Law and how to act in coordination between the Royal Prerogative and the Parliament of England, which placed subtle limits to royal power rather than the blunt limits placed in Scotland. [1]

Sir Adam Newton and Sir Robert Carr.

By and large, James I/VI would leave behind a mixed legacy, as many things he did were excellent and good for the nation and many things he did sparked controversy as well, however the tutorship that he took from the Englishmen undoubtedly aided in his endeavor of the fact that he is generally well regarded today in the British Isles.

***

[1] – Our Primary PoD. James I/VI was asked to be tutored in English law and niceties but was avoided otl, something that was taken up ittl, making James VI more aware of the situation in England around him rather than the somewhat clueless monarch that he was otl.

***