thank you!I really like the story so far and how you explain things, also I like how you introduce the various characters and explain their positions and actions.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Union of Crowns: A Timeline

- Thread starter Sarthak

- Start date

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formed over 100 years early? (200 for ‘and Ireland’)? And the potential for a truly united British Isles without a rebellious Ireland and diverging Scotland?

Sign me up! Rule Britannia!

Sign me up! Rule Britannia!

Well yes, there is a chance, that the Gaelic nobles survive ittl. James was amenable to them iotl before the 1607 flight and rebellionThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formed over 100 years early? (200 for ‘and Ireland’)? And the potential for a truly united British Isles without a rebellious Ireland and diverging Scotland?

Sign me up! Rule Britannia!

I love the union jack, but it'd be fresh and original to see another flag used by the British instead.I hope they keep the scottisch dominated flag, much more original.

I hope they keep the scottisch dominated flag, much more original.

The flag is going to be very different ittl however.I love the union jack, but it'd be fresh and original to see another flag used by the British instead.

Thank you!Good to see you back I can’t wait to see where you go with this TL.

Chapter 3: The Unifier and the Religious King.

Chapter 3: The Unifier and the Religious King.

From The Union of Crowns by Robert William Johnson

“Perhaps the greatest challenge that James would have in his reign would be the issue of religion. England was a religiously divided country. It had thankfully been able to stave off religious conflict of the scale that had happened in France and the Holy Roman Empire, however that didn’t mean that conflict was not burgeoning in the English kingdom. The discrimination against the Catholic Irish, the persecution of the Catholics, and the religious schisms between the various protestant factions of the country was threatening, quietly and subtly which made the threat even greater, of tearing the nation apart. Catholics, Puritans, Dissenters, Lutherans, Anglicans, all inhabited England and all were in competition against one another for more power and influence in the Parliament and the Royal Court.

John Knox.

James inherently distrusted the Presbyterian nature of the Scottish Reformation, which basically outlawed the bishops and had reduced them to a position that was largely extremely ceremonial and had diminished the power of the monarchy over the church, and to James, he didn’t believe there was a point in being the head of the church if he didn’t have power over it. He was enchanted by the Episcopalian traditions of the English Church and the sovereignty and power that the monarch had over the church in England, and wanted to imitate that in Scotland. However both James and his Scottish advisors knew that, creating a totally Episcopalian Church in Scotland in the Kirk was nigh impossible and would have been only possible during the early stages of the Scottish Reformation, if Knox’s views had been different, but venturing on If’s and but’s wasn’t going to be James I’s policy. He needed action. And even though he disregarded the basic functioning of the government, leaving the day to day running of the country to the parliament and the Royal Council, he dedicated his full attention to the intention of uniting the Church of England and Church of Scotland.

a painting of the most prominent signers of the Millenary Petition.

Puritans would prove to be the very first problem that James would have to tackle, and it would prove to be the entry point for James during his early attempts to unite the Church’s. Throughout 1603, Puritan priests and ministers had collected multiple signatures for a petition to James I to hear their theocratic views and to enact several reforms in the Church of England that the Puritans believed that was necessary if Catholicism was to be eradicated on the English nation. The Millenary Petition was signed by around 1,000 people before it was brought to the attention of James. James, who was learned in the arts of theology and was interested in theological debates, decided to hear the Puritans and on January 17, the Hampton Court Conference took place in Hampton Court, where many high ranking Puritans assembled before the King to plead their case for Puritanism.

There, the Puritans handed James their demands for reforms. They demanded the abolition of:-

The members of the conference argued that they were in opposition to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Archbishop John Whitgift’s policy that clergy would have to subscribe to the Book of Common Prayer and the use of vestments. Many puritans argued that the only literature that would be subscribed would be the 39 Articles and the Royal Supremacy. The Petition also argued in favor of removing episcopacy and settling down for a Presbyterian system of church governance.

John Whitgift

Thankfully for the Puritans, Moderates such as John Knewstub and Laurence Chaderton among the Puritans, knew that their new monarch distrusted the Presbyterian system of church governance, and while the petition’s writing had not been modified, during the debate and the conference, Chaderton and Knewstub instead argued that while Bishops could be kept, there needed to be checks and balances to their powers, in the same manner such as the General Assembly of the Kirk in Scotland. James had been initially angered by the idea of creating a true Presbyterian church in England, when he read through the petition and had almost exploded, Chaderton and Knewstub had managed to avail the King, and the King agreed to moderate reforms and to continue hosting theological debates between the Puritans and the Church of England officials. Of the 7 reforms demanded by the Puritans, James agreed to 2. The requirement that Clergymen had to wear surplice was abolished, and was made optional, and the custom of clergymen being forced to live in the Church building was also abolished. These demands were the least controversial of the ones asked of James, and while Whitgift had opposed the two abolitions, the other comprising factions of the Church of England were in favor, as despite the distrust between Anglicans and Puritans, there was still an atmosphere of cooperation between the two.

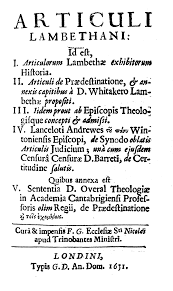

A 1611 version of the Lambeth Articles.

Similarly James was also involved with the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Whitgift in creating the basis for a unified Scottish and English churches. The most important of these acts was the re-introduction of the Lambeth Articles, which had been annulled by Queen Elizabeth I in a fit of anger during 1596. The Lambeth Articles were basically a series of nine doctrinal statements, which were quite similar to Calvinist doctrines, and were drafted and designed by William Whitaker, Humphrey Tundal, the Dean of Ely, and Whitgift himself. The Articles were assigned and signed by Whitgift, Richard Fletcher, the bishop of London, Richard Vaughan, Bishop Elect of Bangor and others as well. And while the articles were extremely similar to Calvinism, they were modified to make them suitable and acceptable for the anti-Calvinists as well. The Lambeth Articles, weren’t new laws, but were defined to be an explanation of already existing laws within the Realm. James who saw the similarities of English Calvinism and Scottish Calvinism through the articles, decided to bring it up once again, and the day after the Hampton Conferences, the Lambeth Articles were once again re-submitted to Cambridge University, this time under the auspices of Royal patronage, rather than the failed attempt of 1595.

The articles, basically declared the following:-

The similarities between the Scottish doctrines were striking in these articles, and James intended to use it to his full advantage. The articles would pass, however unfortunately, Whitgift would not live to see his articles passed in the Synod of Cambridge University, as he died on February 8, 1604. By Royal Grit, James I/VI appointed Richard Vaughan as the new Archbishop of Canterbury to succeed Whitgift in affairs of the Church of England.

Richard Vaughan

The appointment of Vaughan as the Archbishop of Canterbury was perhaps a coup from the Scottish King of England. Vaughan was a moderate and a candidate who was amenable to every faction. [1] As the Bishop of London, his position in the Church of England was unassailable and as a result, he was accepted as the new Archbishop of Canterbury. Politicians in the Parliament did blanch at the appointment of Vaughan however. Vaughan was one of the few people in the Kingdom of Ireland who was capable of speaking Welsh publically and not being prosecuted for it. He was from a Welsh family and spoke Welsh as fluently as he did English. This was largely in part due to his own involvement in the Welsh Bishoprics which preserved the usage of Welsh as their working language. James who came from Scotland and had scores of advisors and men from the Highlands and the Orkneys, who spoke barely any Scots at all, was more than fine with an Archbishop who spoke Welsh. The unassailable position of Vaughan, coupled with his support in the Church of England forced the politicians and Members of Parliament to withdraw their protest at his ascension to the post.

Together with Vaughan and other moderate Puritans and Calvinists, as well as moderate theologians from Scotland, James began to work on his first great theological project. The York Confession of Faith was to be first drafted in York, England on June 1604, to be a confession of the Church of England and a standard of the Church of Scotland. This was a massive undertaking, and while many in Scotland and England opposed this move, many in the Church of England, who supported more consolidation, the Puritans, who supported the supremacy of the royalty, and the Calvinists who supported the supremacy of faith, supported the move of creating a final confessional oath towards the Faith of the country and the people. By this point we can determine that James had moved past his ideas of total episcopacy and was now moving towards what many call a hybrid between episcopacy and Presbyterian systems of governance in the churches of England and Scotland. The Confession of the Faith was to be a systematic exposition of Anglican and Calvinist theology, influenced by Puritanism and Dissenters to a degree. It included common doctrines to other Christian doctrines such as the Trinity and Jesus’s sacrificial death and resurrection, and it contains many doctrines specific to Protestantism as well, such as the Sola Scriptura and the Sola Fide. While Puritanism made no major influence on the work, several hidden and subtle degrees of work in the Confession, such as the minimalistic concept of worship in the Church, had clear Puritan imprints on them.

A painting of a debate between Scottish and English theologians about the Confession of Faith of York.

While the Confession of York would not be ready until late 1605, early 1606, the work and process began in 1604 together with James and Vaaughan.

***

From The Anglo-Spanish Wars: A History by Roland Hill

“After months of negotiations between London and Valladolid, the English and Spaniards were starting to creep closer to a final peace settlement between the two countries. Juan de Tassis was responsible for defusing a lot of tension and was a capable diplomat and represented Spanish interests well, though remaining flexible on English demands. At the end of 1603, the Constable of Castile, arrived into Belgium in Spanish Netherlands to conclude a treaty with England if one could negotiated. With the Constable still waiting in Belgium, a Spanish Habsburg delegation arrived in London on the 19th of May, 1604, and in return an English negotiating team was appointed by Parliament and James I. Under the auspices of both, Robert Cecil, Charles Blount (the 1st Earl of Devonshire), Thomas Sackville (The 1st Earl of Dorset), Henry Howard (the 1st Earl of Northampton), and Charles Howard (the 1st Earl of Nottingham) formed the English delegation to the treaty negotiations, whilst the Spaniards had Juan Fernandez de Velasco, the 5th Duke of Frias, and the Constable of Castile, and Juan de Tassis, as the main negotiating body of the Spanish. They were joined by Charles de Ligne, Jean Richardot and Louis Verreyken as the delegations of the Spanish Netherlands.

Juan Fernandez de Velasco, the 5th Duke of Frias, and the Constable of Castile

The Treaty of London (1604) led to the Spanish renouncing their intentions of restoring the Catholic Church in England and recognized the Protestant Church of England. In return the English swore to end wartime disruption to the Spanish trans-Atlantic shipping and colonial expansion, which had been a key feature of the Anglo-Spanish War that was coming to a close. The English Channel was opened to Spanish shipping and the English withdrew from their intervention in the Dutch Revolt. Ships of both countries were allowed to use the mainland sea ports of the other country for refit, shelter or provisions, with even fleets of less than 8 ships not having to ask for permission. This was a benefit to the English economy as English maritime trade with Spain and its vast empire exploded, which enriched the country, however it was a detriment to the Dutch, as it allowed the Spanish to have a vast network of small interdicting fleets based in and around of English sea ports.

The English and Spanish delegations during the Treaty of London 1604.

The treaty essentially restored the status quo antebellum between London and Valladolid. For the Spanish public, the treaty was extremely popular. Repeated English disruption of the silver trade had nearly bankrupted Spain and the country was war wary after two decades of continuous war with the English. For the English, the reaction was mixed to the treaty. Many believed that England was giving up their natural Protestant Dutch allies to the popish Spaniards, and the popularity of James I plummeted by a good amount after the treaty as many believed that the peace was a humiliating one. The English government however, hailed the peace as a massive diplomatic feat. The English were also tethering on bankruptcy after the combined war with Spain and the Nine Years War in Ireland and the peace allowed the English to gain much needed diplomatic and economic breathing room. James I’s prestige and popularity in the government grew as result.

It was at this point that James I/VI of England and Scotland began to officially begin campaigning, for the lack of a better term, for the unification of Scotland and England into one country known as the Kingdom of Great Britain. Parliament in England, who still liked James VI/I due to his recent education in English Law and the popular treaty, had to subtly tell the monarch that he couldn’t commit himself to calling himself as the King of Great Britain, as that would flout English Law and the Magna Carter. James I accepted this in England, however in Scotland, his official dispatches became signed as King James VI of Scotland and I of Great Britain. Sir Thomas Hamilton, the 1st Earl of Haddington and the Lord Advocate of Scotland, and an extremely able administrator, who was also by and large a supporter of union between Edinburgh and London, raised a personally styled flag that would eventually become the flag of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1613. Haddington, personally seen as the ablest administrator and diplomat that Scotland had to offer at the time, was invited by James I/VI to England so that he could argue the case in front of the English Parliament.

The flag that Haddington raised would eventually become the Flag of Great Britain.

The English Parliament was deeply worried about a political union with Scotland. The normal economic concerns were there, however there were also concerns that the entirety of the English Law and Magna Carter would be abolished due to the union of another country with England on a level term and that in such a situation, the so-called Scottish absolutism would be enforceable in England. Of course James I was far from an absolutist, however the image of the Stuarts, despite James I’s growing popularity, was not at all good in England. Haddington took up this quite uphill battle and he came to London on August 27th, 1604.

Parliament was convened a week later and the members of the parliament began hearing Haddington’s case for the union. Haddington’s argument came from a position of strength and based its argument on the fact that unity would make the security of the countries much more guaranteed and would make the economic position of the isles grow stronger. Haddington had come prepared as well. He drew historical examples, showing the result of the unification of England and the unification of England and Wales as examples of consolidation being good for the overall power of the state. He also pointed towards the recent examples, such as the union of England and Ireland, which had undoubtedly strengthened England, and the union between Castile and Aragon, which had virtually given birth to the Spanish Empire as everyone knew it. The growing free border between Scotland and England had also allowed the economies of both nations to increase at a rate never seen before, and trading macroeconomic trends started to rise favorable to both countries and Haddington brought data to back up his statements. These were all hard facts that every MP, grudgingly had to admit were true. However the issue of English Law, and Absolutism remained. It was here that James I and Haddington pulled out their ace. James I had been studying English Law for the past full year thoroughly and knew that its deposition would be impossible in English society. As a result, he settled for a simple but effective idea. Compromise. He pointed out to Parliament that even Scotland was unwilling to go into union without the preservation of the Scots Law, and yet they were very pro-union. As a result, he declared that by Royal Writ, English Law and the Magna Carter would be retained in the case of union between England and Scotland.

Sir Thomas Hamilton, the 1st Earl of Haddington and Lord Advocate of Scotland.

This was the first time that the English Parliament was swayed slightly in favour of union. Despite the fact that the 1604 Haddington Conference as it came to be known, did not lead to union, it became the very first foundation for the Acts of the Union in 1612. Debates would certainly take up the entirety of Scotland and England’s political time between the upcoming nine years.”

---

[1] – He was a moderate Anglican/Calvinist Syncretic, and was favorable to moderate Puritanism and was liked by all factions in the Church of England.

From The Union of Crowns by Robert William Johnson

“Perhaps the greatest challenge that James would have in his reign would be the issue of religion. England was a religiously divided country. It had thankfully been able to stave off religious conflict of the scale that had happened in France and the Holy Roman Empire, however that didn’t mean that conflict was not burgeoning in the English kingdom. The discrimination against the Catholic Irish, the persecution of the Catholics, and the religious schisms between the various protestant factions of the country was threatening, quietly and subtly which made the threat even greater, of tearing the nation apart. Catholics, Puritans, Dissenters, Lutherans, Anglicans, all inhabited England and all were in competition against one another for more power and influence in the Parliament and the Royal Court.

John Knox.

James inherently distrusted the Presbyterian nature of the Scottish Reformation, which basically outlawed the bishops and had reduced them to a position that was largely extremely ceremonial and had diminished the power of the monarchy over the church, and to James, he didn’t believe there was a point in being the head of the church if he didn’t have power over it. He was enchanted by the Episcopalian traditions of the English Church and the sovereignty and power that the monarch had over the church in England, and wanted to imitate that in Scotland. However both James and his Scottish advisors knew that, creating a totally Episcopalian Church in Scotland in the Kirk was nigh impossible and would have been only possible during the early stages of the Scottish Reformation, if Knox’s views had been different, but venturing on If’s and but’s wasn’t going to be James I’s policy. He needed action. And even though he disregarded the basic functioning of the government, leaving the day to day running of the country to the parliament and the Royal Council, he dedicated his full attention to the intention of uniting the Church of England and Church of Scotland.

a painting of the most prominent signers of the Millenary Petition.

Puritans would prove to be the very first problem that James would have to tackle, and it would prove to be the entry point for James during his early attempts to unite the Church’s. Throughout 1603, Puritan priests and ministers had collected multiple signatures for a petition to James I to hear their theocratic views and to enact several reforms in the Church of England that the Puritans believed that was necessary if Catholicism was to be eradicated on the English nation. The Millenary Petition was signed by around 1,000 people before it was brought to the attention of James. James, who was learned in the arts of theology and was interested in theological debates, decided to hear the Puritans and on January 17, the Hampton Court Conference took place in Hampton Court, where many high ranking Puritans assembled before the King to plead their case for Puritanism.

There, the Puritans handed James their demands for reforms. They demanded the abolition of:-

The usage of the sign of the cross during baptism

The rite of confirmation

The performance of baptism by midwives

The exchanging of rings between spouses during a marriage ceremony.

The ceremonious bowing at the name of Jesus during worship.

The requirement that clergy wear the surplice.

The custom of clergymen being forced to live inside the church building.

The members of the conference argued that they were in opposition to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Archbishop John Whitgift’s policy that clergy would have to subscribe to the Book of Common Prayer and the use of vestments. Many puritans argued that the only literature that would be subscribed would be the 39 Articles and the Royal Supremacy. The Petition also argued in favor of removing episcopacy and settling down for a Presbyterian system of church governance.

John Whitgift

Thankfully for the Puritans, Moderates such as John Knewstub and Laurence Chaderton among the Puritans, knew that their new monarch distrusted the Presbyterian system of church governance, and while the petition’s writing had not been modified, during the debate and the conference, Chaderton and Knewstub instead argued that while Bishops could be kept, there needed to be checks and balances to their powers, in the same manner such as the General Assembly of the Kirk in Scotland. James had been initially angered by the idea of creating a true Presbyterian church in England, when he read through the petition and had almost exploded, Chaderton and Knewstub had managed to avail the King, and the King agreed to moderate reforms and to continue hosting theological debates between the Puritans and the Church of England officials. Of the 7 reforms demanded by the Puritans, James agreed to 2. The requirement that Clergymen had to wear surplice was abolished, and was made optional, and the custom of clergymen being forced to live in the Church building was also abolished. These demands were the least controversial of the ones asked of James, and while Whitgift had opposed the two abolitions, the other comprising factions of the Church of England were in favor, as despite the distrust between Anglicans and Puritans, there was still an atmosphere of cooperation between the two.

A 1611 version of the Lambeth Articles.

Similarly James was also involved with the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Whitgift in creating the basis for a unified Scottish and English churches. The most important of these acts was the re-introduction of the Lambeth Articles, which had been annulled by Queen Elizabeth I in a fit of anger during 1596. The Lambeth Articles were basically a series of nine doctrinal statements, which were quite similar to Calvinist doctrines, and were drafted and designed by William Whitaker, Humphrey Tundal, the Dean of Ely, and Whitgift himself. The Articles were assigned and signed by Whitgift, Richard Fletcher, the bishop of London, Richard Vaughan, Bishop Elect of Bangor and others as well. And while the articles were extremely similar to Calvinism, they were modified to make them suitable and acceptable for the anti-Calvinists as well. The Lambeth Articles, weren’t new laws, but were defined to be an explanation of already existing laws within the Realm. James who saw the similarities of English Calvinism and Scottish Calvinism through the articles, decided to bring it up once again, and the day after the Hampton Conferences, the Lambeth Articles were once again re-submitted to Cambridge University, this time under the auspices of Royal patronage, rather than the failed attempt of 1595.

The articles, basically declared the following:-

The eternal election of some to lie, and reprobation of others to death

The moving cause of predestination to life is not the foreknowledge of faith and good works, but only the good pleasure of God.

The number of the elect is unalterably fixed.

Those who are not predestined to life shall necessarily be damned for their sins.

The true faith of the elect never fails finally nor totally.

A true believer, or one furnished with justifying faith, has a full assurance and certainty of remission and everlasting salvation in Christ.

Saving grace is not communicated to all men.

No man can come to the Son unless the Father shall draw him, but all men are drawn by the Father.

It is not in every one’s will and power to be saved.

The similarities between the Scottish doctrines were striking in these articles, and James intended to use it to his full advantage. The articles would pass, however unfortunately, Whitgift would not live to see his articles passed in the Synod of Cambridge University, as he died on February 8, 1604. By Royal Grit, James I/VI appointed Richard Vaughan as the new Archbishop of Canterbury to succeed Whitgift in affairs of the Church of England.

Richard Vaughan

The appointment of Vaughan as the Archbishop of Canterbury was perhaps a coup from the Scottish King of England. Vaughan was a moderate and a candidate who was amenable to every faction. [1] As the Bishop of London, his position in the Church of England was unassailable and as a result, he was accepted as the new Archbishop of Canterbury. Politicians in the Parliament did blanch at the appointment of Vaughan however. Vaughan was one of the few people in the Kingdom of Ireland who was capable of speaking Welsh publically and not being prosecuted for it. He was from a Welsh family and spoke Welsh as fluently as he did English. This was largely in part due to his own involvement in the Welsh Bishoprics which preserved the usage of Welsh as their working language. James who came from Scotland and had scores of advisors and men from the Highlands and the Orkneys, who spoke barely any Scots at all, was more than fine with an Archbishop who spoke Welsh. The unassailable position of Vaughan, coupled with his support in the Church of England forced the politicians and Members of Parliament to withdraw their protest at his ascension to the post.

Together with Vaughan and other moderate Puritans and Calvinists, as well as moderate theologians from Scotland, James began to work on his first great theological project. The York Confession of Faith was to be first drafted in York, England on June 1604, to be a confession of the Church of England and a standard of the Church of Scotland. This was a massive undertaking, and while many in Scotland and England opposed this move, many in the Church of England, who supported more consolidation, the Puritans, who supported the supremacy of the royalty, and the Calvinists who supported the supremacy of faith, supported the move of creating a final confessional oath towards the Faith of the country and the people. By this point we can determine that James had moved past his ideas of total episcopacy and was now moving towards what many call a hybrid between episcopacy and Presbyterian systems of governance in the churches of England and Scotland. The Confession of the Faith was to be a systematic exposition of Anglican and Calvinist theology, influenced by Puritanism and Dissenters to a degree. It included common doctrines to other Christian doctrines such as the Trinity and Jesus’s sacrificial death and resurrection, and it contains many doctrines specific to Protestantism as well, such as the Sola Scriptura and the Sola Fide. While Puritanism made no major influence on the work, several hidden and subtle degrees of work in the Confession, such as the minimalistic concept of worship in the Church, had clear Puritan imprints on them.

A painting of a debate between Scottish and English theologians about the Confession of Faith of York.

While the Confession of York would not be ready until late 1605, early 1606, the work and process began in 1604 together with James and Vaaughan.

***

From The Anglo-Spanish Wars: A History by Roland Hill

“After months of negotiations between London and Valladolid, the English and Spaniards were starting to creep closer to a final peace settlement between the two countries. Juan de Tassis was responsible for defusing a lot of tension and was a capable diplomat and represented Spanish interests well, though remaining flexible on English demands. At the end of 1603, the Constable of Castile, arrived into Belgium in Spanish Netherlands to conclude a treaty with England if one could negotiated. With the Constable still waiting in Belgium, a Spanish Habsburg delegation arrived in London on the 19th of May, 1604, and in return an English negotiating team was appointed by Parliament and James I. Under the auspices of both, Robert Cecil, Charles Blount (the 1st Earl of Devonshire), Thomas Sackville (The 1st Earl of Dorset), Henry Howard (the 1st Earl of Northampton), and Charles Howard (the 1st Earl of Nottingham) formed the English delegation to the treaty negotiations, whilst the Spaniards had Juan Fernandez de Velasco, the 5th Duke of Frias, and the Constable of Castile, and Juan de Tassis, as the main negotiating body of the Spanish. They were joined by Charles de Ligne, Jean Richardot and Louis Verreyken as the delegations of the Spanish Netherlands.

Juan Fernandez de Velasco, the 5th Duke of Frias, and the Constable of Castile

The Treaty of London (1604) led to the Spanish renouncing their intentions of restoring the Catholic Church in England and recognized the Protestant Church of England. In return the English swore to end wartime disruption to the Spanish trans-Atlantic shipping and colonial expansion, which had been a key feature of the Anglo-Spanish War that was coming to a close. The English Channel was opened to Spanish shipping and the English withdrew from their intervention in the Dutch Revolt. Ships of both countries were allowed to use the mainland sea ports of the other country for refit, shelter or provisions, with even fleets of less than 8 ships not having to ask for permission. This was a benefit to the English economy as English maritime trade with Spain and its vast empire exploded, which enriched the country, however it was a detriment to the Dutch, as it allowed the Spanish to have a vast network of small interdicting fleets based in and around of English sea ports.

The English and Spanish delegations during the Treaty of London 1604.

The treaty essentially restored the status quo antebellum between London and Valladolid. For the Spanish public, the treaty was extremely popular. Repeated English disruption of the silver trade had nearly bankrupted Spain and the country was war wary after two decades of continuous war with the English. For the English, the reaction was mixed to the treaty. Many believed that England was giving up their natural Protestant Dutch allies to the popish Spaniards, and the popularity of James I plummeted by a good amount after the treaty as many believed that the peace was a humiliating one. The English government however, hailed the peace as a massive diplomatic feat. The English were also tethering on bankruptcy after the combined war with Spain and the Nine Years War in Ireland and the peace allowed the English to gain much needed diplomatic and economic breathing room. James I’s prestige and popularity in the government grew as result.

It was at this point that James I/VI of England and Scotland began to officially begin campaigning, for the lack of a better term, for the unification of Scotland and England into one country known as the Kingdom of Great Britain. Parliament in England, who still liked James VI/I due to his recent education in English Law and the popular treaty, had to subtly tell the monarch that he couldn’t commit himself to calling himself as the King of Great Britain, as that would flout English Law and the Magna Carter. James I accepted this in England, however in Scotland, his official dispatches became signed as King James VI of Scotland and I of Great Britain. Sir Thomas Hamilton, the 1st Earl of Haddington and the Lord Advocate of Scotland, and an extremely able administrator, who was also by and large a supporter of union between Edinburgh and London, raised a personally styled flag that would eventually become the flag of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1613. Haddington, personally seen as the ablest administrator and diplomat that Scotland had to offer at the time, was invited by James I/VI to England so that he could argue the case in front of the English Parliament.

The flag that Haddington raised would eventually become the Flag of Great Britain.

The English Parliament was deeply worried about a political union with Scotland. The normal economic concerns were there, however there were also concerns that the entirety of the English Law and Magna Carter would be abolished due to the union of another country with England on a level term and that in such a situation, the so-called Scottish absolutism would be enforceable in England. Of course James I was far from an absolutist, however the image of the Stuarts, despite James I’s growing popularity, was not at all good in England. Haddington took up this quite uphill battle and he came to London on August 27th, 1604.

Parliament was convened a week later and the members of the parliament began hearing Haddington’s case for the union. Haddington’s argument came from a position of strength and based its argument on the fact that unity would make the security of the countries much more guaranteed and would make the economic position of the isles grow stronger. Haddington had come prepared as well. He drew historical examples, showing the result of the unification of England and the unification of England and Wales as examples of consolidation being good for the overall power of the state. He also pointed towards the recent examples, such as the union of England and Ireland, which had undoubtedly strengthened England, and the union between Castile and Aragon, which had virtually given birth to the Spanish Empire as everyone knew it. The growing free border between Scotland and England had also allowed the economies of both nations to increase at a rate never seen before, and trading macroeconomic trends started to rise favorable to both countries and Haddington brought data to back up his statements. These were all hard facts that every MP, grudgingly had to admit were true. However the issue of English Law, and Absolutism remained. It was here that James I and Haddington pulled out their ace. James I had been studying English Law for the past full year thoroughly and knew that its deposition would be impossible in English society. As a result, he settled for a simple but effective idea. Compromise. He pointed out to Parliament that even Scotland was unwilling to go into union without the preservation of the Scots Law, and yet they were very pro-union. As a result, he declared that by Royal Writ, English Law and the Magna Carter would be retained in the case of union between England and Scotland.

Sir Thomas Hamilton, the 1st Earl of Haddington and Lord Advocate of Scotland.

This was the first time that the English Parliament was swayed slightly in favour of union. Despite the fact that the 1604 Haddington Conference as it came to be known, did not lead to union, it became the very first foundation for the Acts of the Union in 1612. Debates would certainly take up the entirety of Scotland and England’s political time between the upcoming nine years.”

---

[1] – He was a moderate Anglican/Calvinist Syncretic, and was favorable to moderate Puritanism and was liked by all factions in the Church of England.

Very interesting how the church will impact politics going forward, also really love how you show that the in will be a hard fought process politically and that it will take a long time to be finalized and accepted

thank you! Indeed, political processes such as national union do take a lot of time to succeed.Very interesting how the church will impact politics going forward, also really love how you show that the in will be a hard fought process politically and that it will take a long time to be finalized and accepted

Thank you! Hope i measure up!Nice TL so far. Am watching this with anticipation.

I gotta say, the Haddington flag is one heck of a confusing flag for Great Britain ttl

Yeah I don’t think it looks good. I think the Scottish dominated flag originally posted is betterI gotta say, the Haddington flag is one heck of a confusing flag for Great Britain ttl

I gotta say, the Haddington flag is one heck of a confusing flag for Great Britain ttl

It was actually a preliminary flag that was made by Haddington OTL, except instead of the welsh dragon, the welsh cross was placed in the middle. It served the basis of Cromwell's flag. Before 1649 all attempts to unite Britain had this flag thrown around, but the Cromwell using the flag kind of killed the idea after 1660.Yeah I don’t think it looks good. I think the Scottish dominated flag originally posted is better

Huh, interesting!It was actually a preliminary flag that was made by Haddington OTL, except instead of the welsh dragon, the welsh cross was placed in the middle. It served the basis of Cromwell's flag. Before 1649 all attempts to unite Britain had this flag thrown around, but the Cromwell using the flag kind of killed the idea after 1660.

I guess you could say that !Huh, interesting!I guess Cromwell did one good thing OTL after all hahaha

See, THAT is some interesting stuff!Also just going to have to point out by this point that this alternate gbr will be involved in the continents religious wars unlike otl where they remained aloof.

Share: