You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Union of Crowns: A Timeline

- Thread starter Sarthak

- Start date

The problem is that all Eng-Scot-Ireland flags are pretty horrible, and even worse if Wales is integrated. I'm semi-convinced it's not possible to integrate all 3 or 4 flags together like that, I've never seen one that did it successfully. It might be better to go with a design that isn't just a mash-up, but is fresh and merely uses the same coolours or something. Not sure what that would be though.

Also, in this timeline ScotNats (should they exist, this is before nationalism was invented) will not be able to pretend that union was forced on them as some sort of dastardly English plot like they do OTL. It's a Scottish King doing most of the work, and the Scottish Parliament is more in favour of it than the English one.

Also, in this timeline ScotNats (should they exist, this is before nationalism was invented) will not be able to pretend that union was forced on them as some sort of dastardly English plot like they do OTL. It's a Scottish King doing most of the work, and the Scottish Parliament is more in favour of it than the English one.

Or the protectorate jack could also work

I don't know enough about the history of St David's cross but I know that instead of the english invented satire a cross pattee could be used for its association with st patrickprotectorate flag minus sigil isn't bad imo:

View attachment 655884

replacing 2nd english flag with welsh dragon:

View attachment 655885

and replacing irish and welsh symbols with crosses to match england and scotland (does have the problem of those crosses not being symbols for those countries in that time period):

View attachment 655889

Well they won't all survive, but a good portion of them will. And yes them surviving will lead to a massive butterfly barrage on Irish history. The Protestant Ascendancy is going to be heavily sidelined ittl.The survival of the native Irish nobility will have huge ramifications since one of the main driving factors behind Irish discontent with the union is the fact that they were relegated to a second class citizen status in their own country with the anglo-scottish protestant ascendancy.

A surviving Irish nobility is a massive deal, after all there's a reason why the flight of the earls is such a culturally significantly event in Irish history.

Perhaps vary it slightly by using the Scottish blue on the field and making the Irish shield larger?yeah the more i think about it, i think the otl Protectorate Flag would be best.

Chapter 5: The Inevitable Backlash

The Union of Crowns

Chapter 5: The Inevitable Backlash

***

From The Great Matches of Europe by Philip de Klerk

“The negotiations between England and Brandenburg for a marriage alliance continued, and after some time, negotiations began to break through. English diplomats led by Sir James Walter in Brandenburg began to plan for a proper betrothal proposal to the Brandenburg Nobility and Royal Family, as well the heir to the electorate, John Sigismund, who was also the father of Maria Eleonora, the intended and sought after.

The English King, James I/VI wanted to make sure that he had a Protestant match for his eldest two, Henry and Elizabeth, whilst he searched for a domestic and or catholic match for his younger children, Charles, the Duke of York and the newly born Mary Stuart, who was only 1 by the time the English diplomats had managed to break through with the Brandenburgers in Berlin.

Joachim Frederick, the Elector of Brandenburg

Joachim Frederick, the Elector of Brandenburg was also keen for an alliance with England, one of the chief leading Protestant monarchies in Europe, and as the relations between the Catholic South in the Holy Roman Empire and the Protestant north in the Holy Roman Empire continued to deteriorate with every new event in the empire, Joachim Frederick knew that he needed to have diplomatic failsaves in and outside of the Germanies as well. And England provided this opportunity to the man.

On April 8, 1606, Joachim Frederick, after months of negotiations and bargaining finally agreed to betrothe Maria Eleonora, his granddaughter to Prince Henry Frederick of England. The two were soon betrothed in absentia during the month of April, 1606, and it was negotiated that Maria Eleonora would be transferred to the English court in the year of 1612, and then marry Prince Henry Frederick in 1615. The marriage would be a mixed marriage. Prince Henry, who would later become Henry I of Great Britain, and Maria Eleonora were in love with one another, and two deeply pined for each other and loved each other dearly, however politicking took up much of Henry’s time, and Maria’s mental illness, which had never been stable to say the least, interfered with the couple’s life in the future. Nonetheless, the two had a fruitful life with one another, and the two would go on to have five children, of whom three would survive into adulthood and continue the line of the family.”

***

From The Union of Crowns by Robert William Johnson

“On May 18, 1606, after much haggling and much negotiating, the English Parliament finally agreed to open negotiations with the Scottish Parliament regarding the unification of the currencies of England and Scotland, abolishing the Scots Pound and the English Pound to form the British Pound.

Many economic factors came into play as the Scottish and English Lords and Parliamentarians, as well as the respective treasuries began to look into matters of rate and exchange. This time in Scottish Economic History was significant, not only the quantitative expansion of traditional textiles of the country, but also due to the rise of extractive industries, which made the issue of currency swapping all the more harder in Scotland. Under the goodwill of the crown and the English, several significant steps had been made to force the pace of technical change and diversify the range of products being produced in the Scottish Kingdom. The communication of technical knowledge and immigration of skilled craftsmen from Ireland and England allowed the country to have an innovationist class, and several mines in the country started to employ more and more English merchants to become their agents across the markets of England and the continent.

a scottish farm in the 1600s

The English economy was too growing at an astonishing rate, despite some of its revenue problems. Historians have found enterprising farmers such as Robert Loder of Harwell in Berkshire, and Henry Best of Elmswell in Yorkshire who had entrepreneurial skills necessary to bring about changes in farming techniques to increase both food production and farm and agricultural profits as well. There is little doubt that under the combined pressure of a rapidly growing population and the development of food markets across the channel in the Low Countries, English farming had made astonishing strides under the early rule of the Stuarts adopting new crops and techniques, most notably new fodder crops that enabled more animals to be kept alive during winter and so ensuring a stable supply of fertilizers and by extending the area under cultivation, most notably by the reclamation of several expanses of marshlands in Eastern England under the vast engineering skills of talented engineers like Giles Vermuyden (Vermuyden was a Dutch engineer involved in land reclamation against the sea and his guild was appointed by the treasury for reclamation in East Anglia).

With the opening of Scottish markets without the barrier of a hard border, the English wool industry boomed as well, and English wool became one of Scotland’s most valued commodities. All of these economic advancements, partially of which was due to the personal union between London and Edinburgh, the issue of uniting the English and Scottish currencies became all the more complex and harder. However, led by able economists such as Tobias Gentleman and Thomas Mun, the English and Scottish Parliaments formed the ‘Anglo-Scottish Economic Committee’ which was dedicated to uniting the currencies and fixing the economies of the two countries together.

Ludovic Stewart, the 2nd Duke of Lennox

Ludovic Stewart, the 2nd Duke of Lennox, the Lord High Commissioner of the Scottish Parliament, who was a trusted manager and administrator to James I/VI, became involved from the Scottish side, and Sir Francis Bacon led the charge of actually getting the currency changed.

On October 29, 1606, the Great British Pound was established in Scotland and England, and replaced the English Pound and Scots Pound. It was deemed that 2 English Pounds would be equal to 1 Great British Pound whereas 10 Scots Pound would be equal to 1 Great British Pound. Using this, new coins and banknotes were issued from both Scotland and England regarding the new currency. The government of both Scotland and England designated the year 1620 as the last year until which the Scots Pound and English Pound would be valid, and have a time period of nearly one and a half decade for the peoples of their respective countries to exchange their savings for the new currency.

Economic reforms were made both in England and Scotland as well. Both the Royal Navy of England and the Scottish Royal Navy began to coordinate the amount of merchant shipping that the two built to increase the efficiency of British trade with another in the isles, and both the Scottish and English antiquated revenue systems were updated and reformed, along Habsburg and French lines, both of whom had better and more efficient economic systems during the time. The Antiquated Scottish and English Book of Rates, which used 1567 and 1560 rates respectively, were old and backwards and not up to date with early modern inflationary rates. As a result, they were updated, and the new rates allowed both Edinburgh and London to levy moderately higher custom dues on rates that allowed them to levy higher revenues from their respective nations.

The monetary union between England and Scotland, also increased the project of uniting the English and Scottish Kingdoms. All that was really left was the project of uniting the English and Scottish Churches as the next step forward for uniting the two countries once and for all.

There was only one problem. The name of the united church of Britain, and who would be the head of the church (other than the monarch of course). The name issue was solved quickly when James VI/I by Royal Writ named the Church as the Church of Britain and the Britannic Communion. However the issue of which Church official, the Archbishop of Canterbury or the Moderate of the Kirk, becoming the Monarch’s appointed representative in the newly forming Church remained an issue. Obviously, the Scots wanted the Moderator of the Kirk to become the Leader of the new Church and the English wanted the Archbishop of Canterbury to fulfil that role. Puritans and Protestants in Ireland also wanted the Archbishop of Armagh, their Primate, to be involved and made important during the religious confirmation.

Richard Vaughan

As such there was an issue. Where would the primate of the Church of Britain be? In Scotland? In England? In Ireland? The answer was not a single of those aforementioned countries. Richard Vaughan, the Archbishop of Canterbury, ever the wily and cunning compromiser, decided that neither of the constituent countries under the personal union were suited to hold the primate, as choosing one would simply alienate the other. Vaughan thus chose a peculiar area for the Primate of the Church of Britain. The Lordship of Mann was chosen by Vaughan to be the seat of the Primate. He argued that it was in the center of all three nations looking for union and as such represented an equidistant from all, which would treat all three equally. The new Moderator of the Kirk, James Law also settled the issue about the Kirk vs Canterbury issue. Since the Presbyterian and Episcopal systems of England and Scotland had been virtually mixed together in the York Confession of the Faith, he deemed that for the system to be truly decentralized, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Archbishop of Armagh and the Moderator of the Kirk would all be subservient to the Archbishop of Mann who would be the overall head of the Primate of the Church of Britain. Since the decentralized system of the Britannic Communion meant that a general assembly of bishops were required, the Primates of Scotland, England and Ireland would also remained autonomous within their own constituent kingdoms.

However of course, this settlement did disgruntle several people in the three kingdoms. Already discontent at the notion of union with their age old enemy, three ambitious lords of Scotland, who had already been scheming since 1604 to rebel, used the pretext of the Britannic Communion to rebel in June 9, 1606. George Gordon, the 1st Marquess of Huntly, John Gordon, the 13th Earl of Sutherland and Patrick Stewart, the 2nd Earl of Orkney all rebelled against James VI/I imploring him to stop his unification methods and to restore the status quo. Thus began the Highlander War.”

***

From Anglo-British Colonialism in the Early Modern Era by Robert MacMillan

“On December 28, 1605, the North American Company was founded as an English Joint-Stock Company by James I of England. It was to be a company of Knights, Merchants and Adventurers, and planters from the cities of Bristol, Exeter and Plymouth. It’s basic and inherent purpose was to establish settlements on the coast of North America, between 35 to 45 Degrees of northern latitude within 100 miles of the Seaboard. The merchants who were involved in the establishment of the company also agreed to finance the settler’s trips in return for repayment of their expenses plus interest out of profits made.

George Calvert

The main power behind the project was George Calvert who was made 1st Baron Baltimore in 1605. Calvert came from a long line of Anglo-Flemish nobility in England that had settled down there after the 100 Years War and though the Yorkshire Branch of the Calverts, from which Baltimore hailed, was a very minor noble family, they still had the basic perks that came from being a part of the nobility during this time. He was extremely linked with Robert Cecil, the Secretary of the State under Elizabeth I and James I of England. In 1604, Cecil was rewarded the title of Earl of Salibsury and Lord High Treasurer and became a member of the English Privy Council as well. As Cecil rose, so did Calvert and by late 1604 he had garnered the attention of the new Scottish King of England. Calvert’s Foreign Languages, legal training and discretion made him an invaluable ally for Robert Cecil as well as the King as well.

Working in the court to improve his standing, Calvert exploited his influence by bribing nobles, extending favors, and accumulating a small amount of influential offices, honors and sinecures. Finally as the question of colonialism raged on in the English court, after a meeting with the King in Oxford in June 1605, he convinced the King that a proper colonial project was required if England was to compete with the domains of Philip III which stretched all across the Americas in the Western Hemisphere.

The question of settlement was disputed as many did not know where a proper settlement could be made. Too far south and the English would be straying into Spanish territory and going far too north and the English would be entering French colonial lands, both of which could spark a colonial war for which England had neither time nor the money nor the resources. As a result, a middle ground was chosen and the Chesepian Bay [1] area was chosen as the perfect landing spot for an English colonial expedition.

On January 17, the first group of explorers under the command of Calvert and Captain Christopher Newport left Dover with around 140 people aboard the HMS Discovery, HMS Godspeed, HMS Susan Constant to the eastern coast of the Americas. After 122 days of sailing across the seas, the three ships finally reached the eastern seaboard of the Americas and began moving up north into the Chesepian Bay before they landed. Calvert named the area that they had landed upon and the subsequent settlement that formed as Anneville [2] after the current queen of England on May 27, 1606.

Flag of the Colony of Virginia, where Anneville was first found.

Soon enough the small ~150 settlers and sailors of the small region that they had settled down in came into contact with the Susquehannock Tribe and the Lenape Tribe. Both of the two native American tribes had been in contact with Europeans, mainly some Dutch traders in the north and French settlers in Acadian regions to the north, where they were in contact with French traders. Whilst many of this Native American groups would both be friend and enemies in the future, for the time being, the two sides met with one another, and using rudimentary signs with one another, they traded with one another, with the English trading wine and tobacco for pelts and other foodstuff that were desperately needed. Thus began the story of the first permanent settlement of the English and British colonizers in the New World.”

***

From The Gaelic Highlands: The War Against Union by Robert MacLeod

“The idea of union with England, whilst widely popular in most parts of the Scottish and Irish community during the early 1600s under the reign of James I of England, it wasn’t universally well received and the attempts to unite the Church of Scotland and the Church of England were all rather fractious for the dissenting nobles. Ever since early 1604, Patrick Stewart, the 2nd Earl of Orkney, a vicious and ruthless man had intrigued with the Scottish nobles hoping to make sure that the Scottish nobles of the Highlands revolted against the union. He also made gains in Ireland, where former Crown allies such as Cahir O’Doherty and Richard Burke, the 4th Earl of Clanricarde, were angered by the survival of the rebel Gaelic Lords after the 9 Years War, since they were promised their lands that they now could not receive under the auspices of the Royal Government.

Patrick Stewart, the 2nd Earl of Orkney

By late 1604, he had gathered his core group of hardline and radical anti-unionists, made up of himself, George Gordon and John Gordon, the 1st Marquess of Huntly and 13th Earl of Sutherland respectively, Cahir O’Doherty and Richard Burke and all planned to rebel against the government of James VI/I when the time was right. Secretly building up their feudal levies, and preparing themselves for an inevitable show of force against the English and Scottish governments, the rebels had a definite goal in mind. Their goal was to attrition the forces sent against them as much as possible to force the King to come to terms with them after the treasury started to run dry. In this they hoped they would be successful. In this manner, they began to prepare themselves.

However in mid-1606 news arrived about the Britannic Communion being passed in the Kirk and the Church of England, and as a result, this was the perfect casus belli for the rebels to use against the central government. On June 9, 1606, they rebelled against the Crown declaring their intention to stop the incoming union, with the use of force if necessary.

The levies were collected by the rebels and then gathered up by the lords, and they began to take up arms against the government. The first to attack was Cahir O’Doherty in Tyrconnell against the English government. Lord Tyrone, once rebel turned loyalist raised his own local army with the support of Lord Mountjoy and marched against O’Doherty. Tyrone had raised around 7,000 men at arms against the 5,000 men that O’Doherty had managed to raise and Tyrone entered hostile territory on June 31, 1606 intent on proving his loyalty to the throne and crown and proving his commitment to the unionist cause. Once O’Doherty found out that Tyrone was coming with a larger army, he began to retreat deeper into his own territory and began to conduct a scorched earth policy as he retreated. However this backfired on O’Doherty as the public opinion in the region quickly turned against him due to this policy. Haggled by starving peasants not wanting to be subject to the scorched earth policy, Tyrone caught up against the rebel troops at Pettigo Plateau.

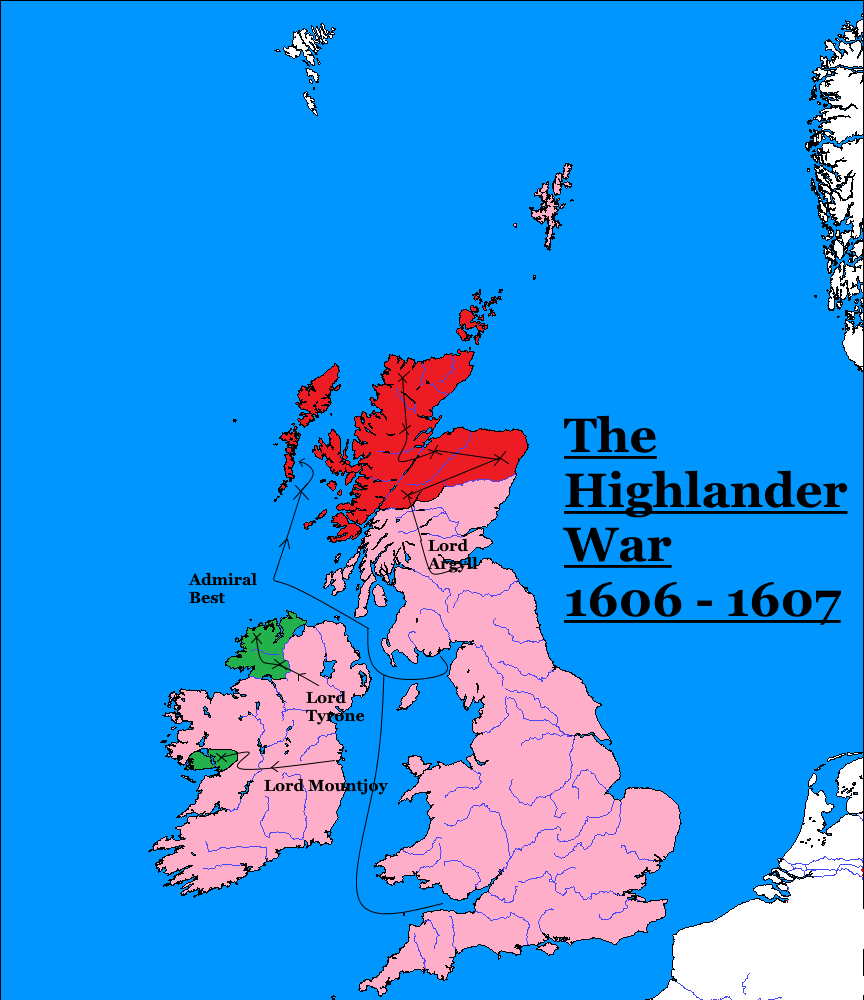

The red lands are held by Highlander rebels and Green lands are held by Irish rebels during the Highlander War.

Fighting through the marshlands, Lord Tyrone and his experience in unsymmetrical and symmetrical warfare won out and at the Battle of Pettigo Plateau, Lord Tyrone defeated O’Doherty and forced the man to flee further into his territory. After resting his troops and re-gathering his forces, Lord Tyrone went on the march again, this time intent on forcing O’Doherty into a decisive battle and catching him.

Near Lough Akkibon, Lord Tyrone caught up with O’Doherty and forced O’Doherty into open battle against the army led by Tyrone. At first O’Doherty and his men managed to defeat the forces of tyrone and pushed them back against the lake, however after regrouping his forces, Tyrone led a cavalry charge against the flanks of O’Doherty’s men and the rebels began to break rank, and general chaos ensued in which O’Doherty was caught by an unsuspecting cavalry trooper, who didn’t recognize the rebel and pushed a sword through his abdomen, killing the rebel leader. During the ending hours of the battle, his body was found, and their spirit broken, the rebels broke rank and fled the battle. The Battle of Losett on the 16th of August, 1606 defeated a part of the rebellion that had been ongoing since two to three months prior in the Tyrconnell region.

Meanwhile in Dublin, Lord Mountjoy had gathered Irish men at arms and the Royal Garrisons in the Pale and had begun to march against Burke. After force marching his troops for two and a half months straight, Lord Mountjoy and his 10,000 men entered hostile territory on Burke’s land. Burke’s policy was to conduct hit and run raids on the enemy, before leaving, to take advantage of his home terrain, however Mountjoy, who was rather accustomed to this kind of strategy from the 9 Years War began to conduct a wide pincer movement throughout Clanricarde region, forcing Burke to seek battle against his choice.

On August 29, 1606, he chose to field an army of around 9,000 rebels against Mountjoy's 8,000 men at the fields of Bothar Nua. Burke however committed a fatal mistake. His men had the River Corrib to their backs, and when the Crown forces began to push against his forces, his men began to drown in the river, as they tried to retreat. The loyalist garrison from Galway also sallied out from the city ad conducted hit and run raids on their flanks, and the rebels began to buckle under the pressure of a two-pronged assault. The next day, having suffered heavy casualties, Burke surrendered his remaining 8,000 men to Mountjoy ending the Battle of Bothar Nua.

The rebellion in Ireland was for all intents and purposes over, and the Crown turned its attention to the Scottish Highlands, where the main show was going on.

By August, both sides in the British mainland had gathered up their forces up to sufficient levels and the Anglo-Scots had placed an army of around 14,000 men under the command of Archibald Campbell, the 7th Earl of Argyll. Meanwhile John Gordon, the 13th Earl of Sutherland commanded the majority of the Highlander forces. On August 8th, 1606, Argyll entered rebel controlled territory and engaged the enemy at the Battle of Fearnan.

Unfortunately for Argyll, his campaign did not begin with a good sign, and Sutherland had hid the majority of his forces in the nearby Tay Forest Park, and this allowed him to conduct a massive flanking maneuver on the Anglo-Scottish force, and routed them. The Battle of Fearnan thus ended in an Anglo-Scottish defeat and the rebels tried to push their advantage. However on August 27, 1606, Argyll had managed to stabilize his army and after receiving some reinforcements from Edinburgh, he decided to conduct a wide attack on Cairngorms area. He marched his army to the northeast, feeding off the sparsely populating, but naturally rich areas of this area, and marched through the thick mountains and lands to reach the lowland areas near Aberdeen. There, on November 18, he caught the rebels who had followed them at the Battle of Inverurie.

The march across Cairngorms had exhausted the Anglo-Scottish Army and they were initially beaten back by the rebels, fighting on their home territory, however after the loyalist Aberdeen garrison broke out of the city and reinforced the Anglo-Scots, Argyll came back out again to offer battle and using a pincer movement through the gaps in the rebel lines, he managed to push the rebels out, inflicting heavy casualties against Sutherland’s forces.

Being pushed back, the rebels had no real choice but to abandon Huntly, and the Anglo-Scottish forces took the town on the 29th of November, 1606. After this both the rebels and the Crown rested up and wintered for the winter of 1606 and 1607. Several skirmishers and sallying attacks did happen and were conducted against the other, but by and large, a major confrontation did not happen and the frontlines generally remained the same.

On January 31, 1607, Argyll decided to move again, and he began marching the 11,000 men he had left with him against the Gordons who had made camp at Tomatin. In what became the biggest battle of the Highlander War, Argyll crept up his 11,000 men against the 10,000 rebels the Gordons had gathered. Argyll did not seek open battle however, and he knew he had to break the rebels thoroughly, and that could not be achieved through battle.

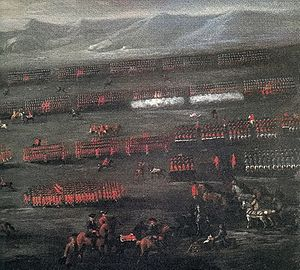

The Battle of Tomatin

When the enemy camp was sleeping, having been lulled into a false sense of security after Argyll retreated in a diversion, on the night of February 28, 1607, the Anglo-Scottish army fell upon the surprised and half asleep rebel camp, slaughtering as they went, basically destroying any fighting power the rebels had left. The 13th Earl of Sutherland and the Marquess of Huntly were both killed in the attack and were slain by the common soldiers under the command of Argyll.

Two more small battles took place at Gorstan and Archfary, however these were small clashes and in both occasions, the Lowland Scottish troops dealt with the Highlanders with brutal efficiency. The only remaining problem that was left was that of Orkney, with his sizeable fleet, he was still a problem and a thorn on the Anglo-Scots in his base in the islands.

English Admiral Sir Thomas Best was given 2 Galleons and 10 Galleys from the Royal Navy and Scottish Navy and asked to defeat the 12 Galley strong fleet that Orkney had gathered up in the past two and a half years. Best sailed to the north and passing the Irish Channel, he made his way into the Northern Atlantic, where he intended to fight. Off the Sound of Barra he caught the fleet commanded personally by the 2nd Earl of Orkney.

In the ensuing naval battle, Best beat the Orkney fleet, using a mass ramming attack the moment he saw the enemy fleet and the English galleys tore through the enemy galleys using the sheer weight of momentum to push the enemy fleet back. The Galleons and their powerful firepower also forced the Orkney fleet to turn back, and return back. It was a small naval battle compared to what was going on between the Spaniards and Dutch, however it was the first English naval battle in quite some time, and as such was celebrated throughout England. With the Orkney fleet obsolete, the Gaelic Clan Lords of Orkney conducted a coup against the 2nd Earl of Orkney on April 27, 1607, and sued for peace, handing the Earl to the Crown. On July 4, 1607, the Peace of Dundee was signed ending the Highlander War. The remaining alive rebels, like Orkney and Burke were not afforded the same leniency as the Gaelic Lords of Ireland had in 1603. They were tried and summarily executed, their titles reverting back to the crown.

The Highlander War also had an interesting effect on the ongoing scheme of uniting the nations. In Scotland, the Lowlander opinion turned decisively in favor of unification as the hated catholic Highlanders had rebelled against the idea, and in Ireland, the Catholics such as Lord Tyrone and Lord Tyrconnell had reaffirmed their loyalty through trial of combat. Their proposals of a proper union were finally being properly discussed after that. In England, the benefit of Irish and Scottish manpower, as seen in the war was shown for its full effectiveness, and local Scottish and Irish commanders and Lord Tyrone and Lord Argyll showed that their talent would be off massive use as well. Ironically the Highlander War which started to stop union, only succeeded in accelerating it.”

***

[1] – Chesapeake Bay ittl. Using one of the earlier names.

[2] – Otl Baltimore

Chapter 5: The Inevitable Backlash

***

From The Great Matches of Europe by Philip de Klerk

“The negotiations between England and Brandenburg for a marriage alliance continued, and after some time, negotiations began to break through. English diplomats led by Sir James Walter in Brandenburg began to plan for a proper betrothal proposal to the Brandenburg Nobility and Royal Family, as well the heir to the electorate, John Sigismund, who was also the father of Maria Eleonora, the intended and sought after.

The English King, James I/VI wanted to make sure that he had a Protestant match for his eldest two, Henry and Elizabeth, whilst he searched for a domestic and or catholic match for his younger children, Charles, the Duke of York and the newly born Mary Stuart, who was only 1 by the time the English diplomats had managed to break through with the Brandenburgers in Berlin.

Joachim Frederick, the Elector of Brandenburg

Joachim Frederick, the Elector of Brandenburg was also keen for an alliance with England, one of the chief leading Protestant monarchies in Europe, and as the relations between the Catholic South in the Holy Roman Empire and the Protestant north in the Holy Roman Empire continued to deteriorate with every new event in the empire, Joachim Frederick knew that he needed to have diplomatic failsaves in and outside of the Germanies as well. And England provided this opportunity to the man.

On April 8, 1606, Joachim Frederick, after months of negotiations and bargaining finally agreed to betrothe Maria Eleonora, his granddaughter to Prince Henry Frederick of England. The two were soon betrothed in absentia during the month of April, 1606, and it was negotiated that Maria Eleonora would be transferred to the English court in the year of 1612, and then marry Prince Henry Frederick in 1615. The marriage would be a mixed marriage. Prince Henry, who would later become Henry I of Great Britain, and Maria Eleonora were in love with one another, and two deeply pined for each other and loved each other dearly, however politicking took up much of Henry’s time, and Maria’s mental illness, which had never been stable to say the least, interfered with the couple’s life in the future. Nonetheless, the two had a fruitful life with one another, and the two would go on to have five children, of whom three would survive into adulthood and continue the line of the family.”

***

From The Union of Crowns by Robert William Johnson

“On May 18, 1606, after much haggling and much negotiating, the English Parliament finally agreed to open negotiations with the Scottish Parliament regarding the unification of the currencies of England and Scotland, abolishing the Scots Pound and the English Pound to form the British Pound.

Many economic factors came into play as the Scottish and English Lords and Parliamentarians, as well as the respective treasuries began to look into matters of rate and exchange. This time in Scottish Economic History was significant, not only the quantitative expansion of traditional textiles of the country, but also due to the rise of extractive industries, which made the issue of currency swapping all the more harder in Scotland. Under the goodwill of the crown and the English, several significant steps had been made to force the pace of technical change and diversify the range of products being produced in the Scottish Kingdom. The communication of technical knowledge and immigration of skilled craftsmen from Ireland and England allowed the country to have an innovationist class, and several mines in the country started to employ more and more English merchants to become their agents across the markets of England and the continent.

a scottish farm in the 1600s

The English economy was too growing at an astonishing rate, despite some of its revenue problems. Historians have found enterprising farmers such as Robert Loder of Harwell in Berkshire, and Henry Best of Elmswell in Yorkshire who had entrepreneurial skills necessary to bring about changes in farming techniques to increase both food production and farm and agricultural profits as well. There is little doubt that under the combined pressure of a rapidly growing population and the development of food markets across the channel in the Low Countries, English farming had made astonishing strides under the early rule of the Stuarts adopting new crops and techniques, most notably new fodder crops that enabled more animals to be kept alive during winter and so ensuring a stable supply of fertilizers and by extending the area under cultivation, most notably by the reclamation of several expanses of marshlands in Eastern England under the vast engineering skills of talented engineers like Giles Vermuyden (Vermuyden was a Dutch engineer involved in land reclamation against the sea and his guild was appointed by the treasury for reclamation in East Anglia).

With the opening of Scottish markets without the barrier of a hard border, the English wool industry boomed as well, and English wool became one of Scotland’s most valued commodities. All of these economic advancements, partially of which was due to the personal union between London and Edinburgh, the issue of uniting the English and Scottish currencies became all the more complex and harder. However, led by able economists such as Tobias Gentleman and Thomas Mun, the English and Scottish Parliaments formed the ‘Anglo-Scottish Economic Committee’ which was dedicated to uniting the currencies and fixing the economies of the two countries together.

Ludovic Stewart, the 2nd Duke of Lennox

Ludovic Stewart, the 2nd Duke of Lennox, the Lord High Commissioner of the Scottish Parliament, who was a trusted manager and administrator to James I/VI, became involved from the Scottish side, and Sir Francis Bacon led the charge of actually getting the currency changed.

On October 29, 1606, the Great British Pound was established in Scotland and England, and replaced the English Pound and Scots Pound. It was deemed that 2 English Pounds would be equal to 1 Great British Pound whereas 10 Scots Pound would be equal to 1 Great British Pound. Using this, new coins and banknotes were issued from both Scotland and England regarding the new currency. The government of both Scotland and England designated the year 1620 as the last year until which the Scots Pound and English Pound would be valid, and have a time period of nearly one and a half decade for the peoples of their respective countries to exchange their savings for the new currency.

Economic reforms were made both in England and Scotland as well. Both the Royal Navy of England and the Scottish Royal Navy began to coordinate the amount of merchant shipping that the two built to increase the efficiency of British trade with another in the isles, and both the Scottish and English antiquated revenue systems were updated and reformed, along Habsburg and French lines, both of whom had better and more efficient economic systems during the time. The Antiquated Scottish and English Book of Rates, which used 1567 and 1560 rates respectively, were old and backwards and not up to date with early modern inflationary rates. As a result, they were updated, and the new rates allowed both Edinburgh and London to levy moderately higher custom dues on rates that allowed them to levy higher revenues from their respective nations.

The monetary union between England and Scotland, also increased the project of uniting the English and Scottish Kingdoms. All that was really left was the project of uniting the English and Scottish Churches as the next step forward for uniting the two countries once and for all.

There was only one problem. The name of the united church of Britain, and who would be the head of the church (other than the monarch of course). The name issue was solved quickly when James VI/I by Royal Writ named the Church as the Church of Britain and the Britannic Communion. However the issue of which Church official, the Archbishop of Canterbury or the Moderate of the Kirk, becoming the Monarch’s appointed representative in the newly forming Church remained an issue. Obviously, the Scots wanted the Moderator of the Kirk to become the Leader of the new Church and the English wanted the Archbishop of Canterbury to fulfil that role. Puritans and Protestants in Ireland also wanted the Archbishop of Armagh, their Primate, to be involved and made important during the religious confirmation.

Richard Vaughan

As such there was an issue. Where would the primate of the Church of Britain be? In Scotland? In England? In Ireland? The answer was not a single of those aforementioned countries. Richard Vaughan, the Archbishop of Canterbury, ever the wily and cunning compromiser, decided that neither of the constituent countries under the personal union were suited to hold the primate, as choosing one would simply alienate the other. Vaughan thus chose a peculiar area for the Primate of the Church of Britain. The Lordship of Mann was chosen by Vaughan to be the seat of the Primate. He argued that it was in the center of all three nations looking for union and as such represented an equidistant from all, which would treat all three equally. The new Moderator of the Kirk, James Law also settled the issue about the Kirk vs Canterbury issue. Since the Presbyterian and Episcopal systems of England and Scotland had been virtually mixed together in the York Confession of the Faith, he deemed that for the system to be truly decentralized, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Archbishop of Armagh and the Moderator of the Kirk would all be subservient to the Archbishop of Mann who would be the overall head of the Primate of the Church of Britain. Since the decentralized system of the Britannic Communion meant that a general assembly of bishops were required, the Primates of Scotland, England and Ireland would also remained autonomous within their own constituent kingdoms.

However of course, this settlement did disgruntle several people in the three kingdoms. Already discontent at the notion of union with their age old enemy, three ambitious lords of Scotland, who had already been scheming since 1604 to rebel, used the pretext of the Britannic Communion to rebel in June 9, 1606. George Gordon, the 1st Marquess of Huntly, John Gordon, the 13th Earl of Sutherland and Patrick Stewart, the 2nd Earl of Orkney all rebelled against James VI/I imploring him to stop his unification methods and to restore the status quo. Thus began the Highlander War.”

***

From Anglo-British Colonialism in the Early Modern Era by Robert MacMillan

“On December 28, 1605, the North American Company was founded as an English Joint-Stock Company by James I of England. It was to be a company of Knights, Merchants and Adventurers, and planters from the cities of Bristol, Exeter and Plymouth. It’s basic and inherent purpose was to establish settlements on the coast of North America, between 35 to 45 Degrees of northern latitude within 100 miles of the Seaboard. The merchants who were involved in the establishment of the company also agreed to finance the settler’s trips in return for repayment of their expenses plus interest out of profits made.

George Calvert

The main power behind the project was George Calvert who was made 1st Baron Baltimore in 1605. Calvert came from a long line of Anglo-Flemish nobility in England that had settled down there after the 100 Years War and though the Yorkshire Branch of the Calverts, from which Baltimore hailed, was a very minor noble family, they still had the basic perks that came from being a part of the nobility during this time. He was extremely linked with Robert Cecil, the Secretary of the State under Elizabeth I and James I of England. In 1604, Cecil was rewarded the title of Earl of Salibsury and Lord High Treasurer and became a member of the English Privy Council as well. As Cecil rose, so did Calvert and by late 1604 he had garnered the attention of the new Scottish King of England. Calvert’s Foreign Languages, legal training and discretion made him an invaluable ally for Robert Cecil as well as the King as well.

Working in the court to improve his standing, Calvert exploited his influence by bribing nobles, extending favors, and accumulating a small amount of influential offices, honors and sinecures. Finally as the question of colonialism raged on in the English court, after a meeting with the King in Oxford in June 1605, he convinced the King that a proper colonial project was required if England was to compete with the domains of Philip III which stretched all across the Americas in the Western Hemisphere.

The question of settlement was disputed as many did not know where a proper settlement could be made. Too far south and the English would be straying into Spanish territory and going far too north and the English would be entering French colonial lands, both of which could spark a colonial war for which England had neither time nor the money nor the resources. As a result, a middle ground was chosen and the Chesepian Bay [1] area was chosen as the perfect landing spot for an English colonial expedition.

On January 17, the first group of explorers under the command of Calvert and Captain Christopher Newport left Dover with around 140 people aboard the HMS Discovery, HMS Godspeed, HMS Susan Constant to the eastern coast of the Americas. After 122 days of sailing across the seas, the three ships finally reached the eastern seaboard of the Americas and began moving up north into the Chesepian Bay before they landed. Calvert named the area that they had landed upon and the subsequent settlement that formed as Anneville [2] after the current queen of England on May 27, 1606.

Flag of the Colony of Virginia, where Anneville was first found.

Soon enough the small ~150 settlers and sailors of the small region that they had settled down in came into contact with the Susquehannock Tribe and the Lenape Tribe. Both of the two native American tribes had been in contact with Europeans, mainly some Dutch traders in the north and French settlers in Acadian regions to the north, where they were in contact with French traders. Whilst many of this Native American groups would both be friend and enemies in the future, for the time being, the two sides met with one another, and using rudimentary signs with one another, they traded with one another, with the English trading wine and tobacco for pelts and other foodstuff that were desperately needed. Thus began the story of the first permanent settlement of the English and British colonizers in the New World.”

***

From The Gaelic Highlands: The War Against Union by Robert MacLeod

“The idea of union with England, whilst widely popular in most parts of the Scottish and Irish community during the early 1600s under the reign of James I of England, it wasn’t universally well received and the attempts to unite the Church of Scotland and the Church of England were all rather fractious for the dissenting nobles. Ever since early 1604, Patrick Stewart, the 2nd Earl of Orkney, a vicious and ruthless man had intrigued with the Scottish nobles hoping to make sure that the Scottish nobles of the Highlands revolted against the union. He also made gains in Ireland, where former Crown allies such as Cahir O’Doherty and Richard Burke, the 4th Earl of Clanricarde, were angered by the survival of the rebel Gaelic Lords after the 9 Years War, since they were promised their lands that they now could not receive under the auspices of the Royal Government.

Patrick Stewart, the 2nd Earl of Orkney

By late 1604, he had gathered his core group of hardline and radical anti-unionists, made up of himself, George Gordon and John Gordon, the 1st Marquess of Huntly and 13th Earl of Sutherland respectively, Cahir O’Doherty and Richard Burke and all planned to rebel against the government of James VI/I when the time was right. Secretly building up their feudal levies, and preparing themselves for an inevitable show of force against the English and Scottish governments, the rebels had a definite goal in mind. Their goal was to attrition the forces sent against them as much as possible to force the King to come to terms with them after the treasury started to run dry. In this they hoped they would be successful. In this manner, they began to prepare themselves.

However in mid-1606 news arrived about the Britannic Communion being passed in the Kirk and the Church of England, and as a result, this was the perfect casus belli for the rebels to use against the central government. On June 9, 1606, they rebelled against the Crown declaring their intention to stop the incoming union, with the use of force if necessary.

The levies were collected by the rebels and then gathered up by the lords, and they began to take up arms against the government. The first to attack was Cahir O’Doherty in Tyrconnell against the English government. Lord Tyrone, once rebel turned loyalist raised his own local army with the support of Lord Mountjoy and marched against O’Doherty. Tyrone had raised around 7,000 men at arms against the 5,000 men that O’Doherty had managed to raise and Tyrone entered hostile territory on June 31, 1606 intent on proving his loyalty to the throne and crown and proving his commitment to the unionist cause. Once O’Doherty found out that Tyrone was coming with a larger army, he began to retreat deeper into his own territory and began to conduct a scorched earth policy as he retreated. However this backfired on O’Doherty as the public opinion in the region quickly turned against him due to this policy. Haggled by starving peasants not wanting to be subject to the scorched earth policy, Tyrone caught up against the rebel troops at Pettigo Plateau.

The red lands are held by Highlander rebels and Green lands are held by Irish rebels during the Highlander War.

Fighting through the marshlands, Lord Tyrone and his experience in unsymmetrical and symmetrical warfare won out and at the Battle of Pettigo Plateau, Lord Tyrone defeated O’Doherty and forced the man to flee further into his territory. After resting his troops and re-gathering his forces, Lord Tyrone went on the march again, this time intent on forcing O’Doherty into a decisive battle and catching him.

Near Lough Akkibon, Lord Tyrone caught up with O’Doherty and forced O’Doherty into open battle against the army led by Tyrone. At first O’Doherty and his men managed to defeat the forces of tyrone and pushed them back against the lake, however after regrouping his forces, Tyrone led a cavalry charge against the flanks of O’Doherty’s men and the rebels began to break rank, and general chaos ensued in which O’Doherty was caught by an unsuspecting cavalry trooper, who didn’t recognize the rebel and pushed a sword through his abdomen, killing the rebel leader. During the ending hours of the battle, his body was found, and their spirit broken, the rebels broke rank and fled the battle. The Battle of Losett on the 16th of August, 1606 defeated a part of the rebellion that had been ongoing since two to three months prior in the Tyrconnell region.

Meanwhile in Dublin, Lord Mountjoy had gathered Irish men at arms and the Royal Garrisons in the Pale and had begun to march against Burke. After force marching his troops for two and a half months straight, Lord Mountjoy and his 10,000 men entered hostile territory on Burke’s land. Burke’s policy was to conduct hit and run raids on the enemy, before leaving, to take advantage of his home terrain, however Mountjoy, who was rather accustomed to this kind of strategy from the 9 Years War began to conduct a wide pincer movement throughout Clanricarde region, forcing Burke to seek battle against his choice.

On August 29, 1606, he chose to field an army of around 9,000 rebels against Mountjoy's 8,000 men at the fields of Bothar Nua. Burke however committed a fatal mistake. His men had the River Corrib to their backs, and when the Crown forces began to push against his forces, his men began to drown in the river, as they tried to retreat. The loyalist garrison from Galway also sallied out from the city ad conducted hit and run raids on their flanks, and the rebels began to buckle under the pressure of a two-pronged assault. The next day, having suffered heavy casualties, Burke surrendered his remaining 8,000 men to Mountjoy ending the Battle of Bothar Nua.

The rebellion in Ireland was for all intents and purposes over, and the Crown turned its attention to the Scottish Highlands, where the main show was going on.

By August, both sides in the British mainland had gathered up their forces up to sufficient levels and the Anglo-Scots had placed an army of around 14,000 men under the command of Archibald Campbell, the 7th Earl of Argyll. Meanwhile John Gordon, the 13th Earl of Sutherland commanded the majority of the Highlander forces. On August 8th, 1606, Argyll entered rebel controlled territory and engaged the enemy at the Battle of Fearnan.

Unfortunately for Argyll, his campaign did not begin with a good sign, and Sutherland had hid the majority of his forces in the nearby Tay Forest Park, and this allowed him to conduct a massive flanking maneuver on the Anglo-Scottish force, and routed them. The Battle of Fearnan thus ended in an Anglo-Scottish defeat and the rebels tried to push their advantage. However on August 27, 1606, Argyll had managed to stabilize his army and after receiving some reinforcements from Edinburgh, he decided to conduct a wide attack on Cairngorms area. He marched his army to the northeast, feeding off the sparsely populating, but naturally rich areas of this area, and marched through the thick mountains and lands to reach the lowland areas near Aberdeen. There, on November 18, he caught the rebels who had followed them at the Battle of Inverurie.

The march across Cairngorms had exhausted the Anglo-Scottish Army and they were initially beaten back by the rebels, fighting on their home territory, however after the loyalist Aberdeen garrison broke out of the city and reinforced the Anglo-Scots, Argyll came back out again to offer battle and using a pincer movement through the gaps in the rebel lines, he managed to push the rebels out, inflicting heavy casualties against Sutherland’s forces.

Being pushed back, the rebels had no real choice but to abandon Huntly, and the Anglo-Scottish forces took the town on the 29th of November, 1606. After this both the rebels and the Crown rested up and wintered for the winter of 1606 and 1607. Several skirmishers and sallying attacks did happen and were conducted against the other, but by and large, a major confrontation did not happen and the frontlines generally remained the same.

On January 31, 1607, Argyll decided to move again, and he began marching the 11,000 men he had left with him against the Gordons who had made camp at Tomatin. In what became the biggest battle of the Highlander War, Argyll crept up his 11,000 men against the 10,000 rebels the Gordons had gathered. Argyll did not seek open battle however, and he knew he had to break the rebels thoroughly, and that could not be achieved through battle.

The Battle of Tomatin

When the enemy camp was sleeping, having been lulled into a false sense of security after Argyll retreated in a diversion, on the night of February 28, 1607, the Anglo-Scottish army fell upon the surprised and half asleep rebel camp, slaughtering as they went, basically destroying any fighting power the rebels had left. The 13th Earl of Sutherland and the Marquess of Huntly were both killed in the attack and were slain by the common soldiers under the command of Argyll.

Two more small battles took place at Gorstan and Archfary, however these were small clashes and in both occasions, the Lowland Scottish troops dealt with the Highlanders with brutal efficiency. The only remaining problem that was left was that of Orkney, with his sizeable fleet, he was still a problem and a thorn on the Anglo-Scots in his base in the islands.

English Admiral Sir Thomas Best was given 2 Galleons and 10 Galleys from the Royal Navy and Scottish Navy and asked to defeat the 12 Galley strong fleet that Orkney had gathered up in the past two and a half years. Best sailed to the north and passing the Irish Channel, he made his way into the Northern Atlantic, where he intended to fight. Off the Sound of Barra he caught the fleet commanded personally by the 2nd Earl of Orkney.

In the ensuing naval battle, Best beat the Orkney fleet, using a mass ramming attack the moment he saw the enemy fleet and the English galleys tore through the enemy galleys using the sheer weight of momentum to push the enemy fleet back. The Galleons and their powerful firepower also forced the Orkney fleet to turn back, and return back. It was a small naval battle compared to what was going on between the Spaniards and Dutch, however it was the first English naval battle in quite some time, and as such was celebrated throughout England. With the Orkney fleet obsolete, the Gaelic Clan Lords of Orkney conducted a coup against the 2nd Earl of Orkney on April 27, 1607, and sued for peace, handing the Earl to the Crown. On July 4, 1607, the Peace of Dundee was signed ending the Highlander War. The remaining alive rebels, like Orkney and Burke were not afforded the same leniency as the Gaelic Lords of Ireland had in 1603. They were tried and summarily executed, their titles reverting back to the crown.

The Highlander War also had an interesting effect on the ongoing scheme of uniting the nations. In Scotland, the Lowlander opinion turned decisively in favor of unification as the hated catholic Highlanders had rebelled against the idea, and in Ireland, the Catholics such as Lord Tyrone and Lord Tyrconnell had reaffirmed their loyalty through trial of combat. Their proposals of a proper union were finally being properly discussed after that. In England, the benefit of Irish and Scottish manpower, as seen in the war was shown for its full effectiveness, and local Scottish and Irish commanders and Lord Tyrone and Lord Argyll showed that their talent would be off massive use as well. Ironically the Highlander War which started to stop union, only succeeded in accelerating it.”

***

[1] – Chesapeake Bay ittl. Using one of the earlier names.

[2] – Otl Baltimore

Deleted member 147978

What will the Parliament of the new union would look like?

I would like to see the ins and outs of it.

I would like to see the ins and outs of it.

Really great, hopefully all of the major and mid level rebel leaders are in a ditch or hanged because if not thats a problem waiting to happen.

Also it will be very interesting how the careers of the victorious lord Argyll and Tyrone will develop after their victory.

Also it will be very interesting how the careers of the victorious lord Argyll and Tyrone will develop after their victory.

They will be described when the appropriate chapter ones don't worryWhat will the Parliament of the new union would look like?

I would like to see the ins and outs of it.

Argyll and Tyrone in particular are going to be interesting because Europe is in the brink of explodingReally great, hopefully all of the major and mid level rebel leaders are in a ditch or hanged because if not thats a problem waiting to happen.

Also it will be very interesting how the careers of the victorious lord Argyll and Tyrone will develop after their victory.

I thought the English and Scottish Fleets of the time would mainly be made up of all gun Race Built Galleons or regular Galleons I say this mainly because I can’t see Galleys surviving all that well in the North Sea or more relatively sheltered Irish sea or any stretch of the Atlantic they will get torn to piece. The only place you really see them in this time period is in the Baltic under the control of the kingdoms there.

I hope no devolved Parliament for Scotland and Ireland.

Also ‘Henry I’ of Great Britain? Not Henry IX? So this time they’re resetting the numbers to further signify the new kingdom?

Also ‘Henry I’ of Great Britain? Not Henry IX? So this time they’re resetting the numbers to further signify the new kingdom?

Last edited:

the galleys were there, but england and Scotland did build a small number of galleys.I thought the English and Scottish Fleets of the time would mainly be made up of all gun Race Built Galleons or regular Galleons I say this mainly because I can’t see Galleys surviving all that well in the North Sea or more relatively sheltered Irish sea or any stretch of the Atlantic they will get torn to piece. The only place you really see them in this time period is in the Baltic under the control of the kingdoms there.

Yes, the Regnal Numbers are reset after the unionI hope no developed Parliament for Scotland and Ireland.

Also ‘Henry I’ of Great Britain? Not Henry IX? So this time they’re resetting the numbers to further signify the new kingdom?

Yes that’s good. It shows that Great Britain and Ireland is a new kingdom not England masquerading as Britain.Yes, the Regnal Numbers are reset after the union

Also I think devolved Scottish and Irish Parliaments are not good and should be avoided.

Share: