You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Isaac's Empire 2.0

- Thread starter Basileus Giorgios

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 53 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The Court at Constantinople in 1327 Chapter Twenty Six: Rulers in Threes Chapter Twenty Seven: Springtime of the Devil An Ethnographic Survey of Rhōmanía in 1330: Part One An Ethnographic Survey of Rhōmanía in 1330: Part Two An Ethnographic Survey of Rhōmanía in 1330: Part Three Europe in 1330 Chapter Twenty Nine: Glory and DeathNice update BG.

Well, a lot of it is thanks to you.

Good update, BG!

Cheers!

Wow great update.Please don't tell me that there will be a long wait for the next part.Because this battle will be epic.

Who knows. I'm afraid I've not yet even begun to write, but perhaps that could change at some point. You'll have to wait and see along with me.

Wait....JURCHEN HORDE!?!

Yup!

I think the nomads will have trouble crossing the Bosporus. Unless they turn around and go back through Anatolia, the Caucuses, the Ukraine and south through the Balkans and try their luck there.

Well, that's what happened in the second Mongol attack of IE 1.0. I may follow that sort of pattern. I may not. You will have to wait and see!

So it begins...

Aye.

Great update, BG. Can't wait to see how the Jusen will go about their attack on the Queen of Cities.

Thanks!

So, the Jurchens are going to be TTL's Mongols?

Anyway, nice update. Can't wait to see how the Romans face this new threat.

Hmmm. The Jurchens are going to fill the space the Mongols did vis a vis the ERE in 2.0, sure, but they're not going to enjoy the same absolute domination that the Mongols of OTL and 1.0 did. After all, they've not conquered China. If anything, the role they're playing is probably at this stage more akin to that of OTL's Seljuk Turks, subduing Muslims and Christians alike.

Buwahahahahahahahahaha.

Ha

Let's see how this goes for Constantinople.

You will see! Why so amusin'?

FDW

Banned

Well, a lot of it is thanks to you.

Yet at the same time, I couldn't hold my end of the bargain as far as background goes. At least I still have an opportunity to try and make it right.

Yet at the same time, I couldn't hold my end of the bargain as far as background goes. At least I still have an opportunity to try and make it right.

Indeed, no rush. Saepe Fidelis has written a piece on Germany in the twelfth century which will be published soon, so I'm far from averse to going "back in time", as it were, to take a look at the history of peoples. I'm happy to wait for your history of the Jurchens!

Any other comments from folks on the main update?

FDW

Banned

Indeed, no rush. Saepe Fidelis has written a piece on Germany in the twelfth century which will be published soon, so I'm far from averse to going "back in time", as it were, to take a look at the history of peoples. I'm happy to wait for your history of the Jurchens!

Any other comments from folks on the main update?

Not just the Jurchens, I'm going to try my hand at the rest of "China" too.

Not just the Jurchens, I'm going to try my hand at the rest of "China" too.

I look forward to it!

Saepe Fidelis' update on the development of IE's Germany in the twelfth century will be posted tonight: keep an eye out!

FDW

Banned

I look forward to it!

Yeah, my hope is to create an "China" with an eye towards the theme you were running with in IE 1.0: A world more connected to and knowledgeable about it's past. Getting rid of the Mongols makes this much this easier, as does a number of other things I'm doing.

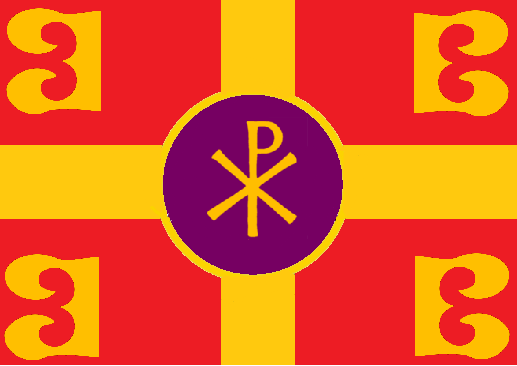

Basileus Giorgos I hope you don't mind I recreated the flag from your original thread.

The German reaction to defeat, 1090-98

That Other Empire

Slightly later than promised, here's my update on developments north of the Alps, where the pseudo-Emperor Henry licks his wounds....

The Diet of Hamburg called in 1090 would be like no other called in Germany. After six years of civil war, the once-deposed, now triumphant Emperor Henry summoned those magnates who, unlike his hapless rival Ekbert, were not already resident in Hamburg, in the Archbishop’s dungeons [1]. Some four hundred nobles and princes of the Church arrived by Michaelmas, knowing full well that the Diet to come would be an ordeal for all. War had left the Empire bereft of leadership; huge swathes of Germany had fallen into lawlessness as even the last vestiges of governance were stripped away during the final months of the war which saw Henry’s Franconian armies burn a swathe through rebellious Saxony before triumphing at Wolfburg. In war, as in all things, to the victor go the spoils and some men arriving on the banks of the Elbe might have felt optimistic; Frederick von Staufen was one of these men. Having sworn Swabia to Henry’s banner in 1087 he was not only one of the first to rebel against Ekbert but also one of Henry’s most consistent supporters. Then there were those like Welf V, a nineteen year-old come into his inheritance too soon after the assassination of his father at the height of the war. His father, another Welf, had supported Henry during his first reign yet had quickly turned to Ekbert’s side after the disaster of Genoa. [2] He came to the Diet having loyally supported the Emperor, but he could not have helped but felt apprehensive given his father’s act of betrayal.

The Diet opened on the Feast of Saint Michael itself [3] with a grand feast in the Archbishop’s hall. Bedecked in the pageantry of the Salian dynasty, wine and ale flowed abundantly, while the guests were served the bounty of the North Sea off of platters of silver. At the High Table itself, the Archbishop himself held the high seat while the Emperor sat to his right. The two talked much together and occasionally with those around them, the Emperor with his son and the Archbishop to Benno of Osnabruck, his erstwhile ally in Church politics. When they retired for the night, some of the guests might have felt relieved. Perhaps this wouldn’t be so bad after all; the Emperor was known for his bouts of fury, yes, but also his swift return to calm. Perhaps he would pursue a modest course after all. Perhaps he would make his peace with them. Other guests, who knew Henry better, knew never to second guess him, and never to underestimate his thirst for revenge.

The Diet of Hamburg lasted three weeks and began with the trial of Ekbert and his ‘rebels’ whom Henry wanted rid of. Presided over by the Emperor himself, the trials would end with the execution of two Dukes, a Margrave, nine Counts, scores of knights and finally the beheading of Ekbert himself, whose pleas for trial by combat were met with a haughty and typically Henrician response, stating that he had already had his trial by arms, and had been found lacking in the eyes of God and man. Henry’s purge of the German aristocracy was followed by a climactic meeting with the assembled nobles who survived his vengeance. Having just seen their compatriots butchered en masse on the cold winter’s morning of the 2nd October on a gallows erected in front of the Episcopal palace, the scions of the realm were herded into the Great Hall by Henry’s retainers to meet their master.

One can only imagine what they felt when they entered and saw Henry, arrayed in full battle armour, seated on a high throne, sword across his knees with his son, Conrad, seated beside him dressed in a miniature version of his father’s resplendent war harness. He announced to them that their old oaths of fealty would have to be repeated and that as Emperor he would brook no further opposition. No one dared point out to him that he was not, technically, Emperor, nor indeed had he ever been. [4] Huddled as they were beneath a-quite literal-sword of Damocles, they prostrated themselves before the Imperial duo and swore their undying allegiance. Bidding them to rise, Henry’s tone then changed. The destroying angel was now gone, or at least retracted his wings and burning sword, and he removed his helmet and gave his sword to a squire. Standing, he announced to them that the past years had proven to them all that the Empire needed to change. He asked them, the assembled gentes of the Empire, to take him once more as their sovereign, and to acclaim him once more their King. In a shout more desperate than joyful, they acceded, and Henry was once more the unquestioned sovereign of Germany.

But what did this mean? Not ten years ago, in his bitter dispute with Pope, the impertinent Gregory had dismissively addressed the self-declared Emperor as Rex Teutonicus, and in response Henry had addressed him simply as ‘Hildebrand’. Even as late as 1148, when preaching Holy War in Livonia the missionary Bishop Hartwig of Uxhale had would refer to the people of Frankfurt as ‘East Franks’, while the Annolied, the mythic history of the Germanic peoples composed in the Rhineland sometime in the early 12th century had traced the origins of the Bavarians to the Christian kingdom of Armenia, the Saxons to Trojan refugees, and the Swabians to the offspring of a lost Roman legion. If the term ‘German’ was widely understood merely as a derogative at this time, then, what can we say it meant to be ‘King of the Germans’, if anything at all? The answer is, of course, nothing; Henry never referred to himself as such and the closest he came was in the second week of the Diet when he had the nobles acclaim his son Conrad ‘Prince of the Germans’ as a means of associating him on the throne [5]. Later historians argued that this period saw the German peoples throw off the shackles of their Roman heritage, emerge from the shadows cast by Otto the Great and Charlemagne and embrace their essential Teutonic nature. This is a pure fallacy which barely merits a response, other than to say that the 11th century was long before the period where language became a source of identification for most Europeans [6]. The next century would be a testing one for the ideology of Imperial rule and it would only be in the 13th century, when contact with fearsome non-European peoples would lead to the solidification of what might be called a ‘German’ identity. The term now commonly used by historians for this period, of the ‘Holy German Empire’ only attained popular use in the early 13th century with the foundation of the Parisian Church [7]. What, then, was Henry?

Everyone knew that the last day of the Diet was going to be a spectacle. Provisions had been arriving from England, Denmark and Saxony for weeks beforehand; food, wine, ale, clothes, ornaments and all the panoply of royal festivities flowed into the city, funded by the extensive Episcopal treasury. The Feast Day of Saint Quadragesimus seemed a fitting, if obscure, end to the proceedings; no doubt it was chosen by one of Henry’s clerical advisors with this symbolism in mind. [8] On this day, Henry was crowned Emperor of the Latins and the Franks while seated on a throne of oak and gold. Invested with the Sword of the Realm by his son, the Prince of the Germans, and the orb by the Archbishop of Mainz, the crown was placed upon his head, auspiciously, by Archbishop Liemar of Hamburg-Bremen. Cloaked not in the furs or tunics of a northern king but in the purple cloak of a Roman Emperor, anointed by holy oils and having sworn before the assembled elites of the new Empire to protect and defend their rights, he was acclaimed Imperator and Dux, and then carried upon the shoulders of his supporters to receive the acclamation of the people of Hamburg, who had been suitably lubricated with free ale by their beneficent Emperor. [9]

It was undoubtedly a magnificent ceremony, and one whose connotations could not have been avoided. The new symbolic importance of the Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen was unprecedented, due no doubt to the personal support Liemar had given Henry during the civil war. Furthermore, his coronation by a reliable German cleric meant the difficulties he had encountered with Gregory would never be encountered by his heirs. Secondly, there is the problem of the title. Emperor of the Latins and the Franks is an intermediary title. Not quite ‘King of the Romans’ or ‘Emperor of Rome’, yet not quite ‘German Emperor’, as it would evolve into in the mid-13th century. Only six men would bear this title, four of them Salians. However this historical period in Germany is known now by another name, one which was given to it by those sticklers for protocol, the East Romans. Sneering at the pretence of the northern warlord they had sent skulking not six years ago, Henry was not Emperor of the Latins and the Franks but rather the somewhat less cumbersome ‘Emperor in the North.’

In late 1090, Henry seemed to have put the issue of Imperial iconography and legitimacy to rest. He was the new Charlemagne, the new Clovis; he had stepped out from beneath his father’s shadow and forged a new political order with himself and, more importantly, his dynasty, at its centre. However the weeks and months following the coronation would see the real business of governance begin. Laid low by years of war, Germany lay prostrate. Having suffered the rapines of pillaging armies and foreign invaders (the Weser had seen longboats bearing the sigil of Denmark glide down its waters for the first time in centuries), Germany had also lost most of its political elite either to war or to Henry’s fury. Now came the part that so many had been looking forward to. In a Golden Bull issued on the Feast of Saint Stephen, he decreed that the allodial lands of all rebels had reverted to the Imperial fisc, and that he intended to enfeof those he saw fit in those lands he saw becoming of their service and their stature. By this decree Bavaria, Thuringia, Lower and Upper Lorraine and Saxony were all seized by Imperial agents in contravention to centuries of theoretical independence [10]. Swabia remained the allodial possession of Frederick von Staufen, who received an Imperial charter recognising him as its sovereign lord and granting him the status of Duke Palatine, with the right to mint his own coinage and set his own tariffs. It also confirmed the Duchy as the hereditary possession of the Staufen dynasty under Salic Law. The second main beneficiary of this reorganisation was Duke Vratislaus of Bohemia, who received from Henry what he had long been promised: a crown. Enthroned as King Vratislaus of Bohemia and Moravia in 1092, he swore homage and fealty to Henry, who embraced him as a brother and processed with him through the streets of Prague. Despite this closeness, Henry had stipulated that the crown was not heritable, and that on his death Bohemia’s throne would be open to an election by its gentes whose preferred candidate would then be ratified by the Emperor.

Across the rest of the Empire, Henry acted to secure the interests of his own family. Bavaria was given to his son, Conrad, as a heritable title that he would hold separately from the Imperial fisc it was expected he would inherit, ensuring that Emperor or no, he and his descendents would be preeminent nobles. Henry retained the Duchies of Saxony and Franconia for himself, although he partitioned Saxony, ceding all lands east of the Elbe to create seven Marches, each headed by a minor Saxon family which had supported Henry, the chief of whom were the Ascania clan, whose patriarch Otto had been declared Duke of Saxony by Henry in 1087 yet who now settled for the title Margrave of Meissen, the old holding of Ekbert which was now greatly augmented to the north until it touched the River Oder. Finally the Lorraine Duchies were completely overhauled, with Theodric the Valiant, another Hencrician loyalist, made the new Duke of Lorraine whose territories stretched from the North Sea along the left bank of the Rhine. As for young Welf, he was given the lesser reward of the new County of Nordgau, a sliver of land separating Bavaria, Bohemia and Saxony. A respectable prize, it was perhaps more than he had expected, and quite possibly more than his family deserved.

Henry’s dispensation of territories placated ambitious lords with the promise of new conquests in the east while rewarded stalwart supporters with rich, well-established fiefdoms to rule as their own. However, by retaining Saxony and Franconia for himself, Henry had placed himself at the centre of a web of landholdings that made his possessions the political centre of the Empire. The final terms that Henry dictated to his new tenants-in-chief was that the Ducal title was now to be granted as a licence from the Imperial Chancellery, headed in from 1092-1098 by the Archbishop of Mainz. These licenses would be conditional on the payment of tax in either cash or kind and could be revoked for a failure to abide by its terms of service. Henry and his heirs would use the renegotiations of licenses that occurred each generation to augment their own power, reward allies, or place restrictions upon rivals. The succeeding centuries would see these new five Duchies change and eventually disintegrate, yet the land distribution of the 1090s was an unprecedented moment of refounding in German history. The old Stem Duchies which had comprised the Empire were swept away and replaced by a new system in which the Imperial office and dynasty were the foremost powers in the land.

[1] Archbishop Liemar of Hamburg, Bishop of Bremen, had received Henry in 1087 when he was overthrown by the Saxon alliance headed by Ekbert of Meissen. Using his connections within the German church and with the rulers of Scandinavia, Liemar would prove instrumental in restoring the Salian dynasty, and some would argue was the real driving force behind Henry’s Imperial project.

[2] In 1084 Henry had been defeated before the walls of Genoa by a (Greek) Imperial force sent to turn him away from Northern Italy. Bereft of an army and hounded across Lombardy, he arrived back in Germany in the spring of 1085 to find a four-way civil war raging in which he was all but an after-thought.

[3] 29th September. As the traditional end of harvest season, Henry is showing an unusual sensitivity to the needs of agriculture which had been so disrupted by warfare. It is estimated that 10-15% of Germany’s population died during these years, due either to warfare, famine or disease.

[4] Henry had been crowned ‘King of the Romans’ in 1065 when he came of age but this was very different from the Imperial title, which required Papal coronation. It was this ambition which led him into conflict first with Gregory VII and eventually with the Eastern Empire.

[5] Associative kingship was widely practiced at this time, as the rules of dynastic legitimacy were shaky at best. Similar to the Eastern Roman practice of appointing co-Emperors, it would eventually pave the way to full hereditary monarchy. The practice was never taken up in post-Conquest England, where dynastic succession was assumed.

[6] The nature of group identification in this time period is an interesting and complex one. There was a traditional tripartite social system, divided between the servitores, pugnatores and oratores, which Henry himself probably assumed to be true and which Pope Gregory VII had challenged by asserting there were only two classes-the priestly caste and then the lay-people. One can still speak of a common Latin civilisation in this time period, as Latin continued to be the language of learned discourse and of governance for centuries. German as a language only became somewhat standardised in the 16th century while the earliest works that could be described as recognisably ‘English’ date from the 14th century and show strong Scandinavian influences, rather than the strong Romance influences the modern language contains.

[7] Founded in 1197 as a joint venture between England and the Empire, the Parisian Orthodox Church was meant to be a counter-balance to the Uniate Church which, it was felt, was dominated by the Eastern Empire and which did not sufficiently take into account the ‘interests’ of the northern monarchies.

[8] His feast day on the 26th October, Saint Quadragesimus is a little-known sixth century Italian saint known mainly for his raising a man from the dead. The parallel to Henry’s resurrection of the Empire might have been lost on the lay nobility, but certainly not on the ecclesiastical chroniclers.

[9] Henry’s coronation is, in many ways, the epitome of the transition in royal/imperial iconography that occurred at this time. Not only is the issue of investiture addressed, with his Imperial Crown being conferred by a German prelate, rather than by the Pope, but his acceptance of the Sword, notably from his son, has strong martial overtones as well as the obvious dynastic links. The contrast between the Purple and the acclamation by nobles and commons is an interesting one too. Theoretically, the Emperors before Henry had been elected by the seven Stem Duchies, who in turn represented the seven Germanic tribes and all their free peoples. Thus the ceremony of acclamation has strong roots in tribal German customs. The wearing of the Purple is clearly, and self-consciously, Roman, and must have been a demonstration by Henry that he hadn’t quite forgotten his Imperial roots. The lifting of the Emperor on his nobles’ shoulders is a nice synthesis of the two traditions; echoing the raising of a Roman Imperator on his soldier’s shields, it also keeps in with the Germanic tradition of acclamation by the people under arms.

[10] The allodial land of the Stem Duchies was theoretically the ancient tribal lands which were held freely by the common people of that area, held by the Duke in their name as their war leader. The amount of land held in fief in Germany before Henry’s revolution was relatively small, and mostly between nobles, rather than land owned by the crown with which he enfeoffed nobles. Indeed, the nature of elective monarchy provided a strong incentive against such practices, as there was no point in building up a system of patronage centred on the crown when the crown might not be succeeded dynastically. Henry’s reforms have been described as ‘feudalisation’ which, while a crude term with too much romanticist and ideological baggage attached to it, describes the situation in some approximation of accuracy.

Slightly later than promised, here's my update on developments north of the Alps, where the pseudo-Emperor Henry licks his wounds....

The Diet of Hamburg called in 1090 would be like no other called in Germany. After six years of civil war, the once-deposed, now triumphant Emperor Henry summoned those magnates who, unlike his hapless rival Ekbert, were not already resident in Hamburg, in the Archbishop’s dungeons [1]. Some four hundred nobles and princes of the Church arrived by Michaelmas, knowing full well that the Diet to come would be an ordeal for all. War had left the Empire bereft of leadership; huge swathes of Germany had fallen into lawlessness as even the last vestiges of governance were stripped away during the final months of the war which saw Henry’s Franconian armies burn a swathe through rebellious Saxony before triumphing at Wolfburg. In war, as in all things, to the victor go the spoils and some men arriving on the banks of the Elbe might have felt optimistic; Frederick von Staufen was one of these men. Having sworn Swabia to Henry’s banner in 1087 he was not only one of the first to rebel against Ekbert but also one of Henry’s most consistent supporters. Then there were those like Welf V, a nineteen year-old come into his inheritance too soon after the assassination of his father at the height of the war. His father, another Welf, had supported Henry during his first reign yet had quickly turned to Ekbert’s side after the disaster of Genoa. [2] He came to the Diet having loyally supported the Emperor, but he could not have helped but felt apprehensive given his father’s act of betrayal.

The Diet opened on the Feast of Saint Michael itself [3] with a grand feast in the Archbishop’s hall. Bedecked in the pageantry of the Salian dynasty, wine and ale flowed abundantly, while the guests were served the bounty of the North Sea off of platters of silver. At the High Table itself, the Archbishop himself held the high seat while the Emperor sat to his right. The two talked much together and occasionally with those around them, the Emperor with his son and the Archbishop to Benno of Osnabruck, his erstwhile ally in Church politics. When they retired for the night, some of the guests might have felt relieved. Perhaps this wouldn’t be so bad after all; the Emperor was known for his bouts of fury, yes, but also his swift return to calm. Perhaps he would pursue a modest course after all. Perhaps he would make his peace with them. Other guests, who knew Henry better, knew never to second guess him, and never to underestimate his thirst for revenge.

The Diet of Hamburg lasted three weeks and began with the trial of Ekbert and his ‘rebels’ whom Henry wanted rid of. Presided over by the Emperor himself, the trials would end with the execution of two Dukes, a Margrave, nine Counts, scores of knights and finally the beheading of Ekbert himself, whose pleas for trial by combat were met with a haughty and typically Henrician response, stating that he had already had his trial by arms, and had been found lacking in the eyes of God and man. Henry’s purge of the German aristocracy was followed by a climactic meeting with the assembled nobles who survived his vengeance. Having just seen their compatriots butchered en masse on the cold winter’s morning of the 2nd October on a gallows erected in front of the Episcopal palace, the scions of the realm were herded into the Great Hall by Henry’s retainers to meet their master.

One can only imagine what they felt when they entered and saw Henry, arrayed in full battle armour, seated on a high throne, sword across his knees with his son, Conrad, seated beside him dressed in a miniature version of his father’s resplendent war harness. He announced to them that their old oaths of fealty would have to be repeated and that as Emperor he would brook no further opposition. No one dared point out to him that he was not, technically, Emperor, nor indeed had he ever been. [4] Huddled as they were beneath a-quite literal-sword of Damocles, they prostrated themselves before the Imperial duo and swore their undying allegiance. Bidding them to rise, Henry’s tone then changed. The destroying angel was now gone, or at least retracted his wings and burning sword, and he removed his helmet and gave his sword to a squire. Standing, he announced to them that the past years had proven to them all that the Empire needed to change. He asked them, the assembled gentes of the Empire, to take him once more as their sovereign, and to acclaim him once more their King. In a shout more desperate than joyful, they acceded, and Henry was once more the unquestioned sovereign of Germany.

But what did this mean? Not ten years ago, in his bitter dispute with Pope, the impertinent Gregory had dismissively addressed the self-declared Emperor as Rex Teutonicus, and in response Henry had addressed him simply as ‘Hildebrand’. Even as late as 1148, when preaching Holy War in Livonia the missionary Bishop Hartwig of Uxhale had would refer to the people of Frankfurt as ‘East Franks’, while the Annolied, the mythic history of the Germanic peoples composed in the Rhineland sometime in the early 12th century had traced the origins of the Bavarians to the Christian kingdom of Armenia, the Saxons to Trojan refugees, and the Swabians to the offspring of a lost Roman legion. If the term ‘German’ was widely understood merely as a derogative at this time, then, what can we say it meant to be ‘King of the Germans’, if anything at all? The answer is, of course, nothing; Henry never referred to himself as such and the closest he came was in the second week of the Diet when he had the nobles acclaim his son Conrad ‘Prince of the Germans’ as a means of associating him on the throne [5]. Later historians argued that this period saw the German peoples throw off the shackles of their Roman heritage, emerge from the shadows cast by Otto the Great and Charlemagne and embrace their essential Teutonic nature. This is a pure fallacy which barely merits a response, other than to say that the 11th century was long before the period where language became a source of identification for most Europeans [6]. The next century would be a testing one for the ideology of Imperial rule and it would only be in the 13th century, when contact with fearsome non-European peoples would lead to the solidification of what might be called a ‘German’ identity. The term now commonly used by historians for this period, of the ‘Holy German Empire’ only attained popular use in the early 13th century with the foundation of the Parisian Church [7]. What, then, was Henry?

Everyone knew that the last day of the Diet was going to be a spectacle. Provisions had been arriving from England, Denmark and Saxony for weeks beforehand; food, wine, ale, clothes, ornaments and all the panoply of royal festivities flowed into the city, funded by the extensive Episcopal treasury. The Feast Day of Saint Quadragesimus seemed a fitting, if obscure, end to the proceedings; no doubt it was chosen by one of Henry’s clerical advisors with this symbolism in mind. [8] On this day, Henry was crowned Emperor of the Latins and the Franks while seated on a throne of oak and gold. Invested with the Sword of the Realm by his son, the Prince of the Germans, and the orb by the Archbishop of Mainz, the crown was placed upon his head, auspiciously, by Archbishop Liemar of Hamburg-Bremen. Cloaked not in the furs or tunics of a northern king but in the purple cloak of a Roman Emperor, anointed by holy oils and having sworn before the assembled elites of the new Empire to protect and defend their rights, he was acclaimed Imperator and Dux, and then carried upon the shoulders of his supporters to receive the acclamation of the people of Hamburg, who had been suitably lubricated with free ale by their beneficent Emperor. [9]

It was undoubtedly a magnificent ceremony, and one whose connotations could not have been avoided. The new symbolic importance of the Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen was unprecedented, due no doubt to the personal support Liemar had given Henry during the civil war. Furthermore, his coronation by a reliable German cleric meant the difficulties he had encountered with Gregory would never be encountered by his heirs. Secondly, there is the problem of the title. Emperor of the Latins and the Franks is an intermediary title. Not quite ‘King of the Romans’ or ‘Emperor of Rome’, yet not quite ‘German Emperor’, as it would evolve into in the mid-13th century. Only six men would bear this title, four of them Salians. However this historical period in Germany is known now by another name, one which was given to it by those sticklers for protocol, the East Romans. Sneering at the pretence of the northern warlord they had sent skulking not six years ago, Henry was not Emperor of the Latins and the Franks but rather the somewhat less cumbersome ‘Emperor in the North.’

In late 1090, Henry seemed to have put the issue of Imperial iconography and legitimacy to rest. He was the new Charlemagne, the new Clovis; he had stepped out from beneath his father’s shadow and forged a new political order with himself and, more importantly, his dynasty, at its centre. However the weeks and months following the coronation would see the real business of governance begin. Laid low by years of war, Germany lay prostrate. Having suffered the rapines of pillaging armies and foreign invaders (the Weser had seen longboats bearing the sigil of Denmark glide down its waters for the first time in centuries), Germany had also lost most of its political elite either to war or to Henry’s fury. Now came the part that so many had been looking forward to. In a Golden Bull issued on the Feast of Saint Stephen, he decreed that the allodial lands of all rebels had reverted to the Imperial fisc, and that he intended to enfeof those he saw fit in those lands he saw becoming of their service and their stature. By this decree Bavaria, Thuringia, Lower and Upper Lorraine and Saxony were all seized by Imperial agents in contravention to centuries of theoretical independence [10]. Swabia remained the allodial possession of Frederick von Staufen, who received an Imperial charter recognising him as its sovereign lord and granting him the status of Duke Palatine, with the right to mint his own coinage and set his own tariffs. It also confirmed the Duchy as the hereditary possession of the Staufen dynasty under Salic Law. The second main beneficiary of this reorganisation was Duke Vratislaus of Bohemia, who received from Henry what he had long been promised: a crown. Enthroned as King Vratislaus of Bohemia and Moravia in 1092, he swore homage and fealty to Henry, who embraced him as a brother and processed with him through the streets of Prague. Despite this closeness, Henry had stipulated that the crown was not heritable, and that on his death Bohemia’s throne would be open to an election by its gentes whose preferred candidate would then be ratified by the Emperor.

Across the rest of the Empire, Henry acted to secure the interests of his own family. Bavaria was given to his son, Conrad, as a heritable title that he would hold separately from the Imperial fisc it was expected he would inherit, ensuring that Emperor or no, he and his descendents would be preeminent nobles. Henry retained the Duchies of Saxony and Franconia for himself, although he partitioned Saxony, ceding all lands east of the Elbe to create seven Marches, each headed by a minor Saxon family which had supported Henry, the chief of whom were the Ascania clan, whose patriarch Otto had been declared Duke of Saxony by Henry in 1087 yet who now settled for the title Margrave of Meissen, the old holding of Ekbert which was now greatly augmented to the north until it touched the River Oder. Finally the Lorraine Duchies were completely overhauled, with Theodric the Valiant, another Hencrician loyalist, made the new Duke of Lorraine whose territories stretched from the North Sea along the left bank of the Rhine. As for young Welf, he was given the lesser reward of the new County of Nordgau, a sliver of land separating Bavaria, Bohemia and Saxony. A respectable prize, it was perhaps more than he had expected, and quite possibly more than his family deserved.

Henry’s dispensation of territories placated ambitious lords with the promise of new conquests in the east while rewarded stalwart supporters with rich, well-established fiefdoms to rule as their own. However, by retaining Saxony and Franconia for himself, Henry had placed himself at the centre of a web of landholdings that made his possessions the political centre of the Empire. The final terms that Henry dictated to his new tenants-in-chief was that the Ducal title was now to be granted as a licence from the Imperial Chancellery, headed in from 1092-1098 by the Archbishop of Mainz. These licenses would be conditional on the payment of tax in either cash or kind and could be revoked for a failure to abide by its terms of service. Henry and his heirs would use the renegotiations of licenses that occurred each generation to augment their own power, reward allies, or place restrictions upon rivals. The succeeding centuries would see these new five Duchies change and eventually disintegrate, yet the land distribution of the 1090s was an unprecedented moment of refounding in German history. The old Stem Duchies which had comprised the Empire were swept away and replaced by a new system in which the Imperial office and dynasty were the foremost powers in the land.

[1] Archbishop Liemar of Hamburg, Bishop of Bremen, had received Henry in 1087 when he was overthrown by the Saxon alliance headed by Ekbert of Meissen. Using his connections within the German church and with the rulers of Scandinavia, Liemar would prove instrumental in restoring the Salian dynasty, and some would argue was the real driving force behind Henry’s Imperial project.

[2] In 1084 Henry had been defeated before the walls of Genoa by a (Greek) Imperial force sent to turn him away from Northern Italy. Bereft of an army and hounded across Lombardy, he arrived back in Germany in the spring of 1085 to find a four-way civil war raging in which he was all but an after-thought.

[3] 29th September. As the traditional end of harvest season, Henry is showing an unusual sensitivity to the needs of agriculture which had been so disrupted by warfare. It is estimated that 10-15% of Germany’s population died during these years, due either to warfare, famine or disease.

[4] Henry had been crowned ‘King of the Romans’ in 1065 when he came of age but this was very different from the Imperial title, which required Papal coronation. It was this ambition which led him into conflict first with Gregory VII and eventually with the Eastern Empire.

[5] Associative kingship was widely practiced at this time, as the rules of dynastic legitimacy were shaky at best. Similar to the Eastern Roman practice of appointing co-Emperors, it would eventually pave the way to full hereditary monarchy. The practice was never taken up in post-Conquest England, where dynastic succession was assumed.

[6] The nature of group identification in this time period is an interesting and complex one. There was a traditional tripartite social system, divided between the servitores, pugnatores and oratores, which Henry himself probably assumed to be true and which Pope Gregory VII had challenged by asserting there were only two classes-the priestly caste and then the lay-people. One can still speak of a common Latin civilisation in this time period, as Latin continued to be the language of learned discourse and of governance for centuries. German as a language only became somewhat standardised in the 16th century while the earliest works that could be described as recognisably ‘English’ date from the 14th century and show strong Scandinavian influences, rather than the strong Romance influences the modern language contains.

[7] Founded in 1197 as a joint venture between England and the Empire, the Parisian Orthodox Church was meant to be a counter-balance to the Uniate Church which, it was felt, was dominated by the Eastern Empire and which did not sufficiently take into account the ‘interests’ of the northern monarchies.

[8] His feast day on the 26th October, Saint Quadragesimus is a little-known sixth century Italian saint known mainly for his raising a man from the dead. The parallel to Henry’s resurrection of the Empire might have been lost on the lay nobility, but certainly not on the ecclesiastical chroniclers.

[9] Henry’s coronation is, in many ways, the epitome of the transition in royal/imperial iconography that occurred at this time. Not only is the issue of investiture addressed, with his Imperial Crown being conferred by a German prelate, rather than by the Pope, but his acceptance of the Sword, notably from his son, has strong martial overtones as well as the obvious dynastic links. The contrast between the Purple and the acclamation by nobles and commons is an interesting one too. Theoretically, the Emperors before Henry had been elected by the seven Stem Duchies, who in turn represented the seven Germanic tribes and all their free peoples. Thus the ceremony of acclamation has strong roots in tribal German customs. The wearing of the Purple is clearly, and self-consciously, Roman, and must have been a demonstration by Henry that he hadn’t quite forgotten his Imperial roots. The lifting of the Emperor on his nobles’ shoulders is a nice synthesis of the two traditions; echoing the raising of a Roman Imperator on his soldier’s shields, it also keeps in with the Germanic tradition of acclamation by the people under arms.

[10] The allodial land of the Stem Duchies was theoretically the ancient tribal lands which were held freely by the common people of that area, held by the Duke in their name as their war leader. The amount of land held in fief in Germany before Henry’s revolution was relatively small, and mostly between nobles, rather than land owned by the crown with which he enfeoffed nobles. Indeed, the nature of elective monarchy provided a strong incentive against such practices, as there was no point in building up a system of patronage centred on the crown when the crown might not be succeeded dynastically. Henry’s reforms have been described as ‘feudalisation’ which, while a crude term with too much romanticist and ideological baggage attached to it, describes the situation in some approximation of accuracy.

Basileus Giorgos I hope you don't mind I recreated the flag from your original thread.

Not at all: thanks!

Slightly later than promised, here's my update on developments north of the Alps, where the pseudo-Emperor Henry licks his wounds....

Very nice, SF. I look forward to hearing more from you on the development of what will become the Holy German Empire as the TL progresses. What did others think of this piece?

This is an excellent thread! Finally caught up, and now I can't wait for the next update!

Thank you!

I do have a couple questions, since it appears that the Jurchens will be invading through Anatolia (to go north and have to punch through Georgia does not seem logical), what is the state of the Byzantine Army? Are they in any shape to give battle?

Hmmm, I'd need to consult my Byzantine army Bible (ie John Haldon's book) on the matter, but that's in London and I'm in Lancashire. So, you'll have to wait a week or so for a definitive answer.

For now, I'd say the paper strength of the army available to the government of George I is probably something approaching 150,000 men, on top of which you can add perhaps another ten to fifteen thousand for the armed retainers of the great nobles. That 150,000 is made up of the professional field troops, the Tagmata, the old garrison troops, the Themata, and the local militia of the notionally independent Italian city states.

That's paper strength: the realistic assessment is going to be considerably less than that. The Themata are now largely worthless in most provinces, fulfilling a role more akin to a local police force, and they are not mobile. In the Armenian frontier provinces they're a little more formidable thanks to the activities of Smbat of Syunik in the previous generation, but even there they're decaying. So, George shouldn't expect more than token support from these men.

The main field armies of East and West, under the control of the Domestikos tēs Dyseōs for the Balkans and the Domestikos tēs Anatolēs for Syria and the upper Euphrates probably comprise around thirty thousand men each. Both are at more or less full strength due to years of peace on both fronts by 1229, but they have something of a dearth of experienced commanders thanks to a combination of peace and Eirene executing most of her best generals in their prime twenty years previously. Probably the Empire's single best field commander is Rōmanos "the Bastard", a castrated son of one of Eirene's Nafpliotid cousins, but Rōmanos' low social standing means he has little more than grudging respect from the rest of the imperial establishment. He's certainly not popular with the Basileus for his sins of being both a Nafpliotid and a considerably better battlefield commander than George is.

Health warning is that this is subject to review when I get John Haldon's book to refer to.

This sort of exposition on an aspect of the Empire was quite fun, I found. If anyone else has any questions about aspects of the pre-Jurchen invasion Empire they'd like me to discuss, please ask away!

Thank you!

As a Basileus once said:

"Less thanking, more updating!

I've got some new ideas that I'll be pinging by you later BG.

I look forward to them!

As a Basileus once said:

"Less thanking, more updating!"

But updates are hard.

I am currently writing a short story written from the perspective of one Alexander Kantakouzenos, set in the reign of Eirene. I hope to publish it here this evening, so watch out!

Threadmarks

View all 53 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The Court at Constantinople in 1327 Chapter Twenty Six: Rulers in Threes Chapter Twenty Seven: Springtime of the Devil An Ethnographic Survey of Rhōmanía in 1330: Part One An Ethnographic Survey of Rhōmanía in 1330: Part Two An Ethnographic Survey of Rhōmanía in 1330: Part Three Europe in 1330 Chapter Twenty Nine: Glory and Death

Share: