Conquest of Space (1940s-2020s)

So, about humankind's TTL reach into outer space. To sum it up, imagine where we would be today with forty more years of active space conquest in the belly, as in For All Mankind tv series.

Reaction by the Entente is at first dispersed, with the UK, France and various Commonwealth nations, and also the US (Robert Goddard), delving into a scattered research effort. However, soon enough, the various research projects within the Commonwealth are unified under British leadership, followed later by expansion of the agreement with a research cooperation agreement with France (minding such agreements were also motivated by the objective of sharing costs, both expanding global funding available and decreasing burden on individual members, thus allowing to outfund and outresearch the German industrial and scientific research sector).

Despite nominal allied status, Russia has been locked out of the cooperation over increasing geopolitical frictions pertaining to the development of colonial emancipation movements and Russian support of them (when New Socialism unconsciously or not furthers old Russian imperialist dreams under guise of anti colonialism).

Prompted by repeated humiliations at the hands of the German space sector, efforts by a kind of "Entente Space Agency"(recycling acronyms is good for the environment ) eventually give fruit. In the 1970s, using superior quality computer technology, the Entente program overtakes the German program for the first time, managing first to deploy and assemble in orbit semi permanently/permanently inhabited space stations in Earth orbit and Earth-Moon Lagrange points. In sheer volume of efforts, ESA was also able to set up the first permanently inhabited Moon base, while the German Moon Base has been slow to expand and has been only hosting astronauts on a semi permanent basis, in a symptom of increasing difficulties by Germany to sustain financially and industrially its effort in the Space Race .

) eventually give fruit. In the 1970s, using superior quality computer technology, the Entente program overtakes the German program for the first time, managing first to deploy and assemble in orbit semi permanently/permanently inhabited space stations in Earth orbit and Earth-Moon Lagrange points. In sheer volume of efforts, ESA was also able to set up the first permanently inhabited Moon base, while the German Moon Base has been slow to expand and has been only hosting astronauts on a semi permanent basis, in a symptom of increasing difficulties by Germany to sustain financially and industrially its effort in the Space Race .

(Credit: For All Mankind 'jamestown base). Just imagine British and French flags picturing prominently above their international partners'

(Credit: For all mankind)

While the Entente space program is blossoming, the German one seemingly collapsed. Political pressure to not be outdone and humiliated led to a mission being scrambled by the IIIrd Reich shortly after the ESA launched its own, only to end in disaster. As later revealed by delving into declassified archives, a faulty hardware and a string of technical malfunctions in life support and/or engines doomed the German mission; though incidents of the kind had already happened before in Earth orbit or between it and the Moon, proximity to Earth had allowed to limit the scope of them as rescue on site or landing back on Earth or on the Moon near bases remained an option. But on a path to Mars, dozens of millions of kilometers away from Earth, no rescue was possible. The German crew, doomed by a failing life support, would commit suicide. Though the exact circumstances of the disaster were dissimulated, the scope of it could hardly be since the whole enterprise had been widely publicized.

It would not be untill the ESA came to its own conclusion of the disaster that had happened, witnessing the German spacecraft pass Mars orbit without any deceleration and continuing its way further towards external solar system, that the Propaganda Ministry would be caught in midst of the worst public relations disaster of its history. For many within the IIIrd Reich, caught by the Counter Culture movement despite state repression, Radio Free Germany or the BBC, listened in secret since illegal, were considered way more reliable information sources than the outlets of the Propaganda Ministry. And as nobody realled bought into brief claims the mission was bound to Jupiter, or the Asteroid belt, admission of an accident was unavoidable.

It would be another five years and two launch windows before the Germans would be able to launch a successfull mission to Mars, making this time a meticulous show of testing and preparation to avoid a repeat, but that would be the swan song of the Nazi space program.

In the hindsight, the Mars Disaster would be considered as one of the triggers in a series of events that led years later to the German revolution and the overthrow of the Nazi regime in Germany. The tragic loss of life, instead of being seen as the heroic sacrifice the Reich presented it to be, was seen as the ultimate price of the regime hubris and disregard for human life value. As such, the German astronauts' death crystallized all the criticisms against the Nazi leadership and turned an already widespread counter culture movement into a political contestation, contributing to the revival of anarcho-syndicalism and the emergence of the Second Circle of Kreisau.

It wouldn't be until the late 2010s that the German space program, having slipped into a semi comatose state after the Revolution, taking a new breath, would effectively return to Mars on its own, independent. Up so far, the newly democratic regime in Germany has relied on cooperation and assistance from the ESA to help supply and maintain its base on the Moon, eventually dropping its own space stations in Earth orbit and Lagrange points to join an International Space Station program with the ESA and renting ESA space facilities for other ventures. On Mars too though, it would join the International Mars Base initiative, but would otherwise focus its efforts into the exploration of the Asteroid belt and its potential for mining, yearning for the potential financial benefits of it.

Meanwhile, German efforts at reviving the Berlin Pact era multinational "cooperation" in the space race, actually nothing more than Germany extorting contributions without any meaningful input or influence, had quickly faltered through out of either indifference or hostility from its former partners.

Though almost twenty years of continuous presence in orbital and Lagrangian space stations and permanent moon bases has guaranteed the political and financial perennity of these enterprises, the continuation of the Mars program looked for a time in trouble. The German Mars disaster and the collapse of Nazi Germany had removed the prime motor of the space race from the equation, and with the ESA under increasing budgetary pressure from its member states, immediate plans for a permanent base on Mars are shelved for the time being, and projects for further manned exploration into the outer system outright cancelled and replaced by unmanned, autonomous probe missions.

For the next 25 years or so, the space program of the ESA would be refocus its efforts on developing its existing missions in Earth-Moon orbits and on the Moon itself, furthering scientific research, and further expanding its commercial activities like TV, internet, GPS and meteo satellites; other areas of interests would involve experiments often with practical and potential exploitable for economic purpose such as micro gravity metalurgy and medical research, satellite waste disposal or helium-3 mining on the Moon. At the same time, it witnessed on its tracks the emergence of private companies as an increasingly influential actor of the space sector.

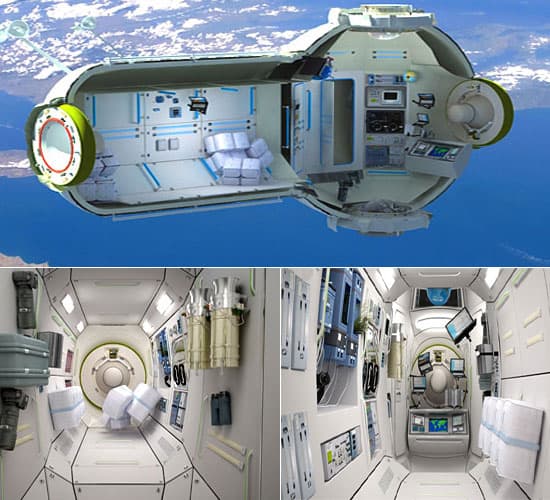

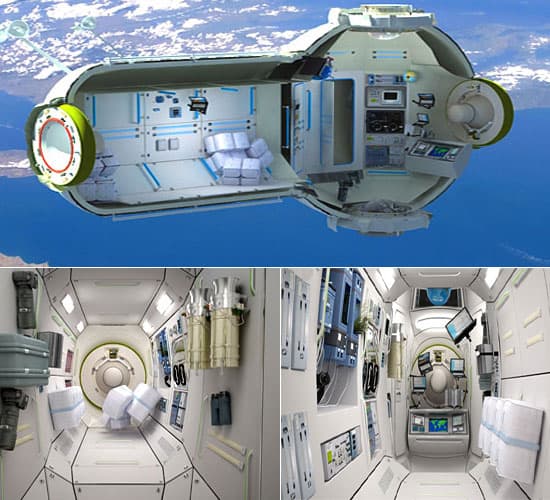

Largely building upon technologies developed, tested and proven by ESA, companies across the World, often set up by ambitious billionaires, some aiming at propping up space tourism with multi million pounds Earth or circumunar orbit week long flights or even stays at "space hotels" (either in the form of refurbished space stations, purpose built ones or even rented space in the Moon bases) for a couple hundred millions; in a more limited and more affordable fashion, suborbital flights were also pursued. But the Holy Grail soon became Asteroid Mining and enticed many investors.

Got a couple dozen million pounds to spend, look up...

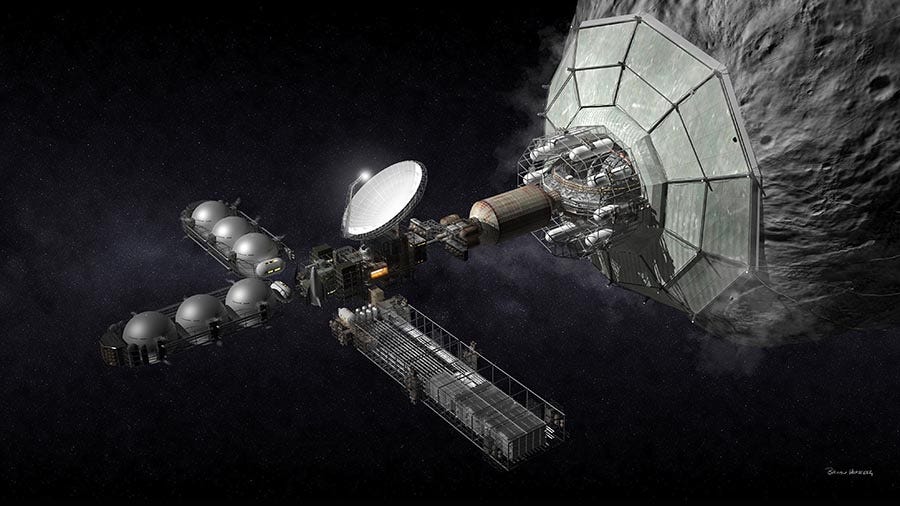

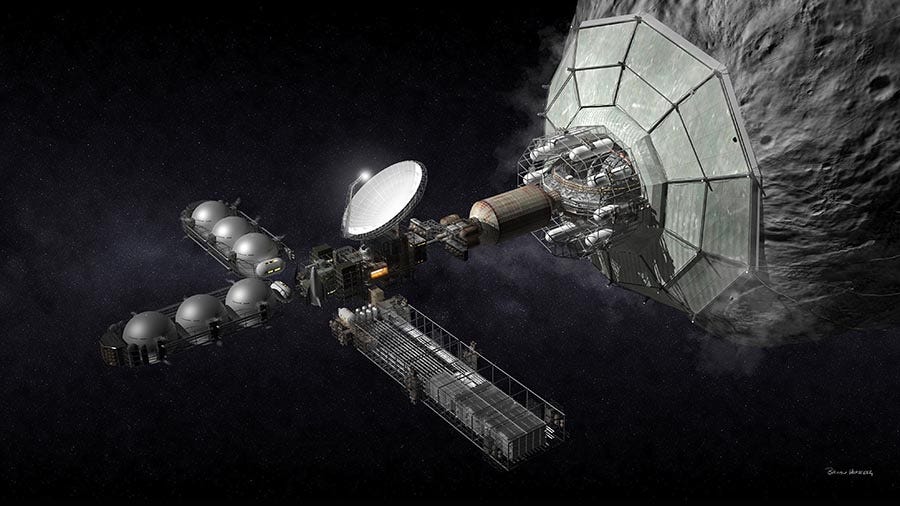

Imagine a test mining project by a public-private partnership in the 2010s

But underneath this apparent commercial venture, the main prize and main pride of the ESA, in conjunction with other space agencies after the model was set by the International Space Station (ISS) and the International Moon Base (IMB), was the resumption of efforts on Mars.

Strictly speaking, the ESA has never totally abandonned manned missions to Mars, but while initial plans had envisioned regular missions to happen, at the pace of one expedition per launch window, not a few had been cancelled and these expeditions have become rather irregular, fluctuating according to the politics of the day and its mood. Exploration was instead relegated to a largely robotic, autonomous effort, with manned missions being decided and programmed when scientific discoveries of great importance and often mediatic importance were considered, such as when a manned mission was launched to investigate presence of water and life on Mars in the 2000s, or when a mission was launched to explore the grandiose setting of Valles Marineris and test blimp probes, along other Martian UAV probes.

ESA's reimagined Mars program began in the second half of the 2010s by setting regular mission, launching expeditions at each orbital window, a flurry of activity never seen since the 1980s, each with the purpose of laying the groundwork for the establishment of a permanent base, taking turns at watching over the construction of the base modules, the reception of heavy (by space transplanetary standards) construction equipment (including the prime use of 3d concrete printing machines experimented on the IMB in the previous decade), their installation and maintainance, and the proper set up of key infrastructure as nuclear fission powered thermoelectric generator for a steady source of energy or the water ice mining fores and other facilities for water and fuel production, aside of a few scientific experiment side projects.

The first permanent Mars inhabitants would come to the base in the mid 2020s. At this time, ESA has also begun building a space station in Martian orbit to handle the increasing traffic and orbit to surface transshipment, to achieve further efficiency and disminish the costs of Martian missions, crucially planning for a fuel depot which would be supplied by production facilities at the surface and would potentially act, like on Moon orbit, as a gateway for exploration further away into the outer solar system, into the gas giants, from the suspected underground oceans of Europa to the liquid methane and ammionac lakes of Titan, with manned missions envisioned as soon as the 2040s.

Yet, because it is perceived as so difficult a task and ignored, they become the unavowed target of both China's and Germany's efforts. While China was seeking to make its name in an already crowded and well cut field and Germany was seeking to prove to itself and to the world it was capable once more of a grandiose feat, both were in their own way looking for a mean to achieve renown and fame by achieving the impossible. While a certainly ambitious objective, in practical terms, it translated by these two nations combined instigating the most exploration missions to these planets, in terms of landing probes and sending satellites to study from orbit, always in the perspective of gathering intelligence for potential manned missions and testing technologies that would be used. These efforts would ultimately justify Germany and China place in the Odyssey Initiative.

After the International Mars Base and the Mars Space Station, the Odyssey Initiative had begun to take shape in the early 2020s when, after many had only dreamed of it, the idea of making a round trip of several years across the solar system, from a flyby of the sun to the outskirts of the Kuiper belt aboard the biggest space ship ever assembled in orbit ever, was endorsed by major figures of the private sector, followed soon by heads of national space agencies and finally governments one after the other. Yet, the Odyssey Initiative remained largely at the planning stage while inter governmental discussions and negotiations unfolded. One of these negotiations had Germany and China, for their current lead in the way of near sun exploration, included to organize and plan the peri solar portion of the planned expedition, meant to take place in twenty years, in the late 2040s.

(Credit: Space Odyssey, BBC 2004) Concept of interplanetary circumsolar spaceship

Returning to the Earth system, private pushed development matured into full fledge space tourism, though still restricted to multi millionaires and billionaires who were the only ones able to afford the tickets for stays on the Moon. That said, a small but steady trend of disminishing fares related to suborbital and low orbit space hotels took root by the early 2020s, leading to the production of several reality TV shows featuring celebrities in space, and even more popular yearly nationwide contests and lotteries for places aboards space stations.

(Credit: Space Cadets tv show) This time around, it might be for real

The craze around this onstart of semi democratization of the space is fueled to new highs when the news eventually breaks out that a child birth happens on the International Moon Base, the first ever human birth recorded out of Earth, a craze that wasn't actually entirely foreign to the launch of the Odyssey Initiative.

EDIT: Summary.

- Opening (1940s-1970s)

My reasoning has always been that a space race where you got the Nazis on one side and the Allies on the other, this being without either Americans or Soviets looting Germany of its brains during the last months of the war to supply their own research programs, would plausibly and likely be way more at Germany's advantage than it was at the Soviets' in the same comparable time frame.

Hence having Nazis on the Moon first.

Reaction by the Entente is at first dispersed, with the UK, France and various Commonwealth nations, and also the US (Robert Goddard), delving into a scattered research effort. However, soon enough, the various research projects within the Commonwealth are unified under British leadership, followed later by expansion of the agreement with a research cooperation agreement with France (minding such agreements were also motivated by the objective of sharing costs, both expanding global funding available and decreasing burden on individual members, thus allowing to outfund and outresearch the German industrial and scientific research sector).

Despite nominal allied status, Russia has been locked out of the cooperation over increasing geopolitical frictions pertaining to the development of colonial emancipation movements and Russian support of them (when New Socialism unconsciously or not furthers old Russian imperialist dreams under guise of anti colonialism).

Prompted by repeated humiliations at the hands of the German space sector, efforts by a kind of "Entente Space Agency"(recycling acronyms is good for the environment

(Credit: For All Mankind 'jamestown base). Just imagine British and French flags picturing prominently above their international partners'

- The German Mars Disaster

Applying the logics of OTL cold war more or less undisturbed, would have necessarily called a further escalation of the space race unlike OTL. The projects for Mars were around in the 1960s and 1970s already, and I think I can argue that the Soviets' utter failure to even follow up on the American landing doomed any prospect of going on Mars anytime soon, which could have happened as soon as the 1980s I figure (and some TLs around the forum all gravitate towards this time period).

(Credit: For all mankind)

While the Entente space program is blossoming, the German one seemingly collapsed. Political pressure to not be outdone and humiliated led to a mission being scrambled by the IIIrd Reich shortly after the ESA launched its own, only to end in disaster. As later revealed by delving into declassified archives, a faulty hardware and a string of technical malfunctions in life support and/or engines doomed the German mission; though incidents of the kind had already happened before in Earth orbit or between it and the Moon, proximity to Earth had allowed to limit the scope of them as rescue on site or landing back on Earth or on the Moon near bases remained an option. But on a path to Mars, dozens of millions of kilometers away from Earth, no rescue was possible. The German crew, doomed by a failing life support, would commit suicide. Though the exact circumstances of the disaster were dissimulated, the scope of it could hardly be since the whole enterprise had been widely publicized.

Going through the draft, I went on thinking a disaster befalling on the Germans was not only plausible but by the sheer implications of it, could be a major era defining event.

More than a few accidents of various gravity happened IOTL in space conquest, but these were rather close to home, and impact could be limited, and somewhat dissimulated if needed. The major parallel I had in mind though was the rescue of the Apollo 13 mission. If something like that had happened on the way to Mars, the picture would have been way darker. Like a submarine sinking below crushing depth during WW2 I imagine, in a cold, silent, solitary, oppressive, inescapable death. When I think of it, the miracle was that all Apollo crews going to the Moon went back safe.

It would not be untill the ESA came to its own conclusion of the disaster that had happened, witnessing the German spacecraft pass Mars orbit without any deceleration and continuing its way further towards external solar system, that the Propaganda Ministry would be caught in midst of the worst public relations disaster of its history. For many within the IIIrd Reich, caught by the Counter Culture movement despite state repression, Radio Free Germany or the BBC, listened in secret since illegal, were considered way more reliable information sources than the outlets of the Propaganda Ministry. And as nobody realled bought into brief claims the mission was bound to Jupiter, or the Asteroid belt, admission of an accident was unavoidable.

It would be another five years and two launch windows before the Germans would be able to launch a successfull mission to Mars, making this time a meticulous show of testing and preparation to avoid a repeat, but that would be the swan song of the Nazi space program.

As I explained before in the TL, my view is that German scientific success was much relying on the back of generations that had grown and studied in the pre Nazi period, and that the intellectually sterile environment of a Nazi led education system would have very possibly spelled the death of that edge. So that's basically there is noone to take up the mantle of von Braun and cie. Add to it the financial and industrial pressure of maintaining the competition with an alliance of nations that have pooled their resources to overpower Germany's lead and have plenty of young and briliant scientists working for them.

In the hindsight, the Mars Disaster would be considered as one of the triggers in a series of events that led years later to the German revolution and the overthrow of the Nazi regime in Germany. The tragic loss of life, instead of being seen as the heroic sacrifice the Reich presented it to be, was seen as the ultimate price of the regime hubris and disregard for human life value. As such, the German astronauts' death crystallized all the criticisms against the Nazi leadership and turned an already widespread counter culture movement into a political contestation, contributing to the revival of anarcho-syndicalism and the emergence of the Second Circle of Kreisau.

Considering the stakes and the publicity to the race, we can safely imagine that noone in Germany will miss about what's going on. That would be like Caucescu famous disaster of a televised speech in 1989, broadcast to millions by state television, that got him discredited and led to his sudden fall. Not decisive in my thinking of the IIIrd Reich collapse, but a contributing and aggravating factor certainly.

It wouldn't be until the late 2010s that the German space program, having slipped into a semi comatose state after the Revolution, taking a new breath, would effectively return to Mars on its own, independent. Up so far, the newly democratic regime in Germany has relied on cooperation and assistance from the ESA to help supply and maintain its base on the Moon, eventually dropping its own space stations in Earth orbit and Lagrange points to join an International Space Station program with the ESA and renting ESA space facilities for other ventures. On Mars too though, it would join the International Mars Base initiative, but would otherwise focus its efforts into the exploration of the Asteroid belt and its potential for mining, yearning for the potential financial benefits of it.

Meanwhile, German efforts at reviving the Berlin Pact era multinational "cooperation" in the space race, actually nothing more than Germany extorting contributions without any meaningful input or influence, had quickly faltered through out of either indifference or hostility from its former partners.

- Consolidation and privatization (1990s-2000s)

Though almost twenty years of continuous presence in orbital and Lagrangian space stations and permanent moon bases has guaranteed the political and financial perennity of these enterprises, the continuation of the Mars program looked for a time in trouble. The German Mars disaster and the collapse of Nazi Germany had removed the prime motor of the space race from the equation, and with the ESA under increasing budgetary pressure from its member states, immediate plans for a permanent base on Mars are shelved for the time being, and projects for further manned exploration into the outer system outright cancelled and replaced by unmanned, autonomous probe missions.

Mars should be less seen as an end than as a mean, ie when you think about the amount of effort to put into such a venture, assuming we already got to the Moon in the meantime and set up space stations too, by the time you actually get to Mars, even if only a few times to show the flag, which is more or less the idea I had in the draft after German failure, the infrastructure developed behind this effort back in Earth orbit and on the Moon is already too large to just subside at the least change of public space policy. Going to Mars is what makes presence in the space stations and on the Moon lasting.

In my scenario, that is by the mid 1980s, rough guess. That means thirty to forty years from today...

Meanwhile IOTL, after the end of the Apollo missions, that was basically lip service with space stations to show the flag from time to time, and we are barely getting back on the road to the Moon, minding all the tech and infrastructure we lost on the way (we had Saturn V rockets back then, but we are kind of starting it all over again). So again, imagine where humankind would be with forty more years of space conquest in the belly, without any discontinuation, without having to start it all over again... forty years more.

For the next 25 years or so, the space program of the ESA would be refocus its efforts on developing its existing missions in Earth-Moon orbits and on the Moon itself, furthering scientific research, and further expanding its commercial activities like TV, internet, GPS and meteo satellites; other areas of interests would involve experiments often with practical and potential exploitable for economic purpose such as micro gravity metalurgy and medical research, satellite waste disposal or helium-3 mining on the Moon. At the same time, it witnessed on its tracks the emergence of private companies as an increasingly influential actor of the space sector.

Largely building upon technologies developed, tested and proven by ESA, companies across the World, often set up by ambitious billionaires, some aiming at propping up space tourism with multi million pounds Earth or circumunar orbit week long flights or even stays at "space hotels" (either in the form of refurbished space stations, purpose built ones or even rented space in the Moon bases) for a couple hundred millions; in a more limited and more affordable fashion, suborbital flights were also pursued. But the Holy Grail soon became Asteroid Mining and enticed many investors.

As of pet projects of bilionaires, there is the obvious examples of today with Space X, but like in the nuclear sector, the private industry is basically ripping the fruits of decades of public investment that allow them to surge on a field with a relatively well developed technology at hand and requiring "relatively" little effort to push further (I say relatively because r&d costs remain quite high, but when in comparison with the cold war programs that brought Sputnik and Apollo missions, you can think they are not so high actually). And with the Mars mission, that's even more true.

Asteroid mining comes into my thinking since, technically, it's easier to get to and off an asteroid than it would be to Mars, because there is almost no gravity to free yourself from to get on the return trip, so the load of a mission, and thus its cost, are considerably reduced. And the mineral wealth of asteroids would be potentially enough to make it profitable with plenty of abundant minerals that are less so on Earth, like when the only surviving ship of Magellan, out of 5, returned to Spain its cargo full of spices and able to refund the expeditions with a large profit. At least, that's what I read often about this sector.

That we are not at this point yet is that asteroids are way less glamorous than the Moon or Mars, and that we have still a lot of knowledge and infrastructure to recover from this cut in the space race I wrote of above. In comparison ITTL, by the 2010s, when the private sector really kicks in, the existing support infrastructure and technology for such ventures is even more developed and way closer at hand than it is to us IOTL.

Got a couple dozen million pounds to spend, look up...

- Mars again (2010s-2020s)

Imagine a test mining project by a public-private partnership in the 2010s

But underneath this apparent commercial venture, the main prize and main pride of the ESA, in conjunction with other space agencies after the model was set by the International Space Station (ISS) and the International Moon Base (IMB), was the resumption of efforts on Mars.

Strictly speaking, the ESA has never totally abandonned manned missions to Mars, but while initial plans had envisioned regular missions to happen, at the pace of one expedition per launch window, not a few had been cancelled and these expeditions have become rather irregular, fluctuating according to the politics of the day and its mood. Exploration was instead relegated to a largely robotic, autonomous effort, with manned missions being decided and programmed when scientific discoveries of great importance and often mediatic importance were considered, such as when a manned mission was launched to investigate presence of water and life on Mars in the 2000s, or when a mission was launched to explore the grandiose setting of Valles Marineris and test blimp probes, along other Martian UAV probes.

ESA's reimagined Mars program began in the second half of the 2010s by setting regular mission, launching expeditions at each orbital window, a flurry of activity never seen since the 1980s, each with the purpose of laying the groundwork for the establishment of a permanent base, taking turns at watching over the construction of the base modules, the reception of heavy (by space transplanetary standards) construction equipment (including the prime use of 3d concrete printing machines experimented on the IMB in the previous decade), their installation and maintainance, and the proper set up of key infrastructure as nuclear fission powered thermoelectric generator for a steady source of energy or the water ice mining fores and other facilities for water and fuel production, aside of a few scientific experiment side projects.

The first permanent Mars inhabitants would come to the base in the mid 2020s. At this time, ESA has also begun building a space station in Martian orbit to handle the increasing traffic and orbit to surface transshipment, to achieve further efficiency and disminish the costs of Martian missions, crucially planning for a fuel depot which would be supplied by production facilities at the surface and would potentially act, like on Moon orbit, as a gateway for exploration further away into the outer solar system, into the gas giants, from the suspected underground oceans of Europa to the liquid methane and ammionac lakes of Titan, with manned missions envisioned as soon as the 2040s.

- Outward (2020s ...)

Yet, because it is perceived as so difficult a task and ignored, they become the unavowed target of both China's and Germany's efforts. While China was seeking to make its name in an already crowded and well cut field and Germany was seeking to prove to itself and to the world it was capable once more of a grandiose feat, both were in their own way looking for a mean to achieve renown and fame by achieving the impossible. While a certainly ambitious objective, in practical terms, it translated by these two nations combined instigating the most exploration missions to these planets, in terms of landing probes and sending satellites to study from orbit, always in the perspective of gathering intelligence for potential manned missions and testing technologies that would be used. These efforts would ultimately justify Germany and China place in the Odyssey Initiative.

After the International Mars Base and the Mars Space Station, the Odyssey Initiative had begun to take shape in the early 2020s when, after many had only dreamed of it, the idea of making a round trip of several years across the solar system, from a flyby of the sun to the outskirts of the Kuiper belt aboard the biggest space ship ever assembled in orbit ever, was endorsed by major figures of the private sector, followed soon by heads of national space agencies and finally governments one after the other. Yet, the Odyssey Initiative remained largely at the planning stage while inter governmental discussions and negotiations unfolded. One of these negotiations had Germany and China, for their current lead in the way of near sun exploration, included to organize and plan the peri solar portion of the planned expedition, meant to take place in twenty years, in the late 2040s.

(Credit: Space Odyssey, BBC 2004) Concept of interplanetary circumsolar spaceship

Returning to the Earth system, private pushed development matured into full fledge space tourism, though still restricted to multi millionaires and billionaires who were the only ones able to afford the tickets for stays on the Moon. That said, a small but steady trend of disminishing fares related to suborbital and low orbit space hotels took root by the early 2020s, leading to the production of several reality TV shows featuring celebrities in space, and even more popular yearly nationwide contests and lotteries for places aboards space stations.

(Credit: Space Cadets tv show) This time around, it might be for real

The craze around this onstart of semi democratization of the space is fueled to new highs when the news eventually breaks out that a child birth happens on the International Moon Base, the first ever human birth recorded out of Earth, a craze that wasn't actually entirely foreign to the launch of the Odyssey Initiative.

And for babies, well, how can I avoid that? That is going to happen at some point. But it's pretty much certain the baby won't grow up on the Moon though and will be repatriated as soon as possible to grow up on good old 9.81 m/s2 Earth gravity acceleration and be monitored as he grows by very affectionate uncles and aunts in clean white coats...

EDIT: Summary.

Late 1950s : Nazi Germany puts first satellite in orbit.

Early 1960s : Nazi Germany puts first man in space, first extravehicular sortie.

Mid 1960s : Nazi Germany puts first man on the Moon.

Late 1960s : The British land on the Moon. Under pressure not to be outdone again by Germany, the UK and France set up a joint space program to share resources and speed up research and development. They are soon joined by other Commonwealth and pro Entente countries.

1970s : Entente is first at setting a permanent Moon base, and at setting space stations in Earth orbit, progressively overtaking Germany in the space race.

Early 1980s : Entente is the first to put astronauts on Mars. The precipitated German mission launched at the same time ends in a catastrophic accident, all crew being lost.

1990s : After the German failure on Mars, the space race ends on an Entente victory. Budgets are cut and exploration projects shelved. Activity is focused back to commercial development and exploitation of Earth orbit. Permanent presence and research efforts are only maintained at the permanent IMB (International Moon Base) and ISS (ATL International Space Station), with Martian exploration entrusted to probes and rovers.

2000s : This decade is marked by ever increasing involvement of private companies in the space sector, first in partnership with public agencies, then autonomously, pursuing development of autonomous space launch capabilities and space tourism (suborbital flight, space hotels). Space hype booms when a TV show with planetary following, sends private citizens, turned astronauts after winning a contest, to the space (or Moon base).

Late 2000s : Riding on the renewed space hype, plans for manned exploration are dusted off, and construction begins on a space station/fuel depot in Moon-Earth Lagrange L1 point

2010s : Manned missions to Mars resume on a regular basis, working to establish a permanent base on Mars' surface and a space station in its orbit.

Late 2010s : First manned mission to an asteroid (Phobos or Deimos perhaps), in a private-public partnership, to test asteroid mining technology.

2020s : First permanent residents on Mars base. Space tourism explodes as fares begin to decrease. Beginning of the Odyssey Initiative.

Last edited: