------------------

Part 19: Death of an Empire, (Re) Birth of Another

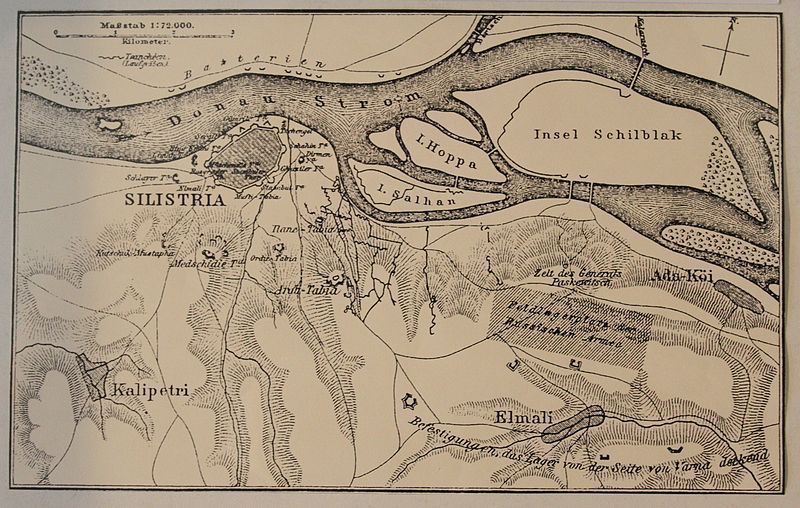

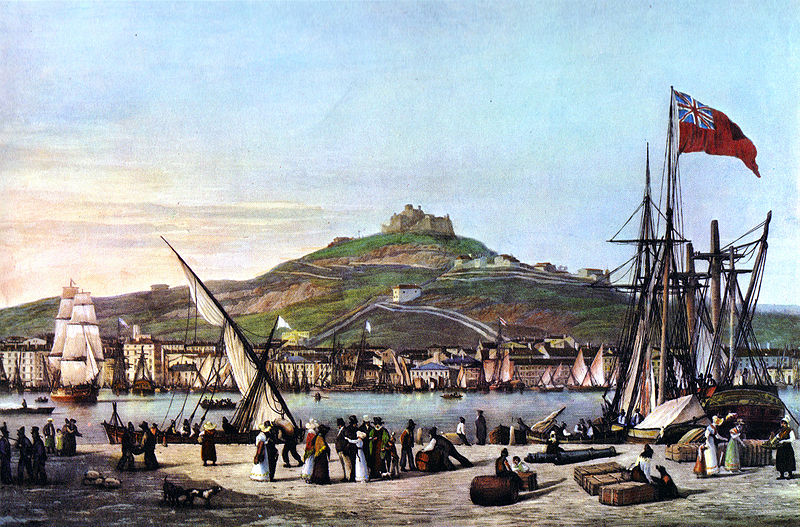

While Napoleon's invasion of Spain is usually seen as the catalyst which started the independence of its colonies, it can be argued that this process began in Argentina almost two years earlier, in June 1806. Since Spain and France were still allies at this point in time, the government of Great Britain attempted to conquer the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, one of the Spanish Crown's most distant colonies. Bereft of reinforcements from the mother country due to the calamitous defeat suffered by the Spanish navy at the Battle of Trafalgar, the local viceroy, Rafael de Sobremonte, had to make do with the few troops at his disposal, and he, believing the British were planning to attack Montevideo, sent most of those troops to reinforce its defenses. This proved to be a costly mistake, for when the British landed on the outskirts of Buenos Aires on June 25, Sobremonte had no choice but to flee to Córdoba, hundreds of kilometers inland, without a fight.

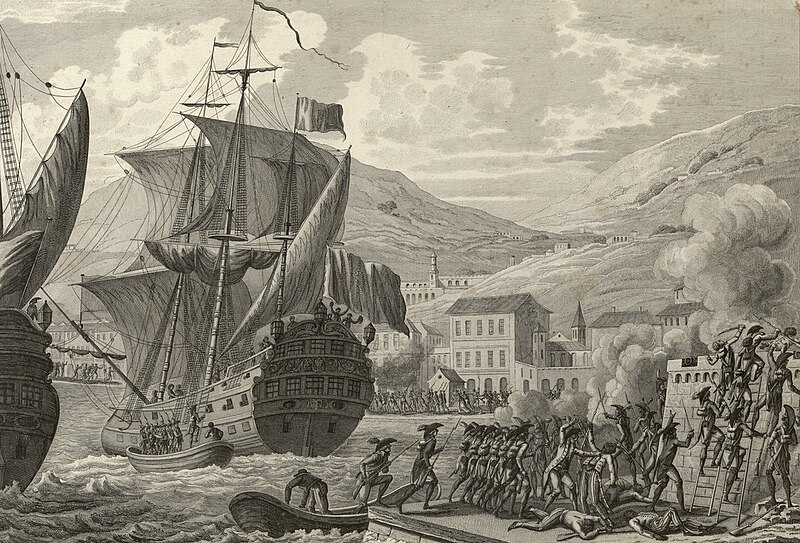

Despite their initial victory, however, the invaders' control of Buenos Aires was short lived. The other major cities of the River Plate were still under Spanish control, providing points from which a counterattack could be launched, while in Buenos Aires itself many locals were displeased with the British occupation. One of these people was Martín de Álzaga, a merchant of Basque descent who, like many of his fellow peninsulares, made a fortune through Spain's monopoly of trade with Buenos Aires, a monopoly the British administration had broken. While he and other like-minded people plotted a rebellion against their occupiers, an army of 1.200 men under the command of Santiago de Liniers was assembled in Montevideo, ready to liberate the viceregal capital once preparations were complete. Liniers' troops approached Buenos Aires on August 4 1806, and they, together with Álzaga's forces, slowly retook the city after days of vicious street fighting. The British commander, William Beresford, capitulated on August 14, and his troops were forced to give up their regimental colours - a great stain on their record (1).

The invaders weren't the only ones humiliated by the campaign's outcome. Rafael de Sobremonte's flight from Buenos Aires was seen as an act of cowardice by the capital's populace, even though he was following a protocol set decades before - indeed, he was actually preparing his own campaign to liberate it, but Liniers got there first. Thus, the porteños (inhabitants of Buenos Aires) decided to demote him from the post of viceroy and install Liniers in his place without waiting for the Spanish Crown's approval, a truly unprecedented action. With the possibility of a second British invasion looming, Liniers' first act as viceroy was to organize and arm a militia of local criollos, the Legión Patricia ("Patricians' Legion"), which would later become the Argentine Army's first regiment. Martín de Álzaga, also hailed a hero, was made mayor of Buenos Aires, and he, together with Liniers, began to strengthen its defenses, ordering the construction of trenches and other fortifications.

Santiago de Liniers and Martín de Álzaga, leaders of the resistance to the British invasions of the River Plate.

The circumstances surrounding their alliance, and its eventual dissolution, sealed the end of Spanish rule in the region.

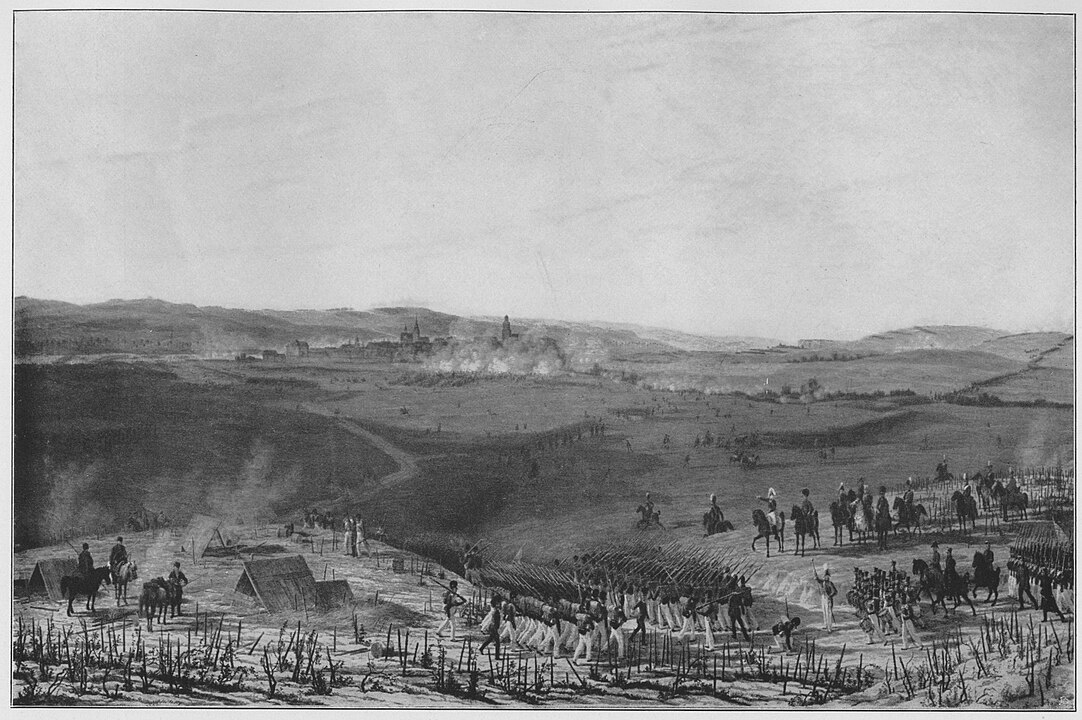

Their worries were well founded: on February 3 1807, a British force several times larger than the one vanquished at Buenos Aires attacked Montevideo, and stormed it before the defenders could get reinforcements. After a few months, during which they consolidated their control over this critical port, the invaders marched against Buenos Aires in early July. Several days of brutal urban fighting ensued, in which the porteño civilians aided their compatriots by doing things such as pouring boiling water and oil on advancing British soldiers from the windows of their homes. In the end, the invaders, weakened by desertions and low morale stemming from their lack of progress, had to not only abort their attempt to capture Buenos Aires, but evacuate Montevideo as well. The people of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata accomplished something truly remarkable: they defeated a powerful foreign army numbering many thousands of men, and they did so without any help from their colonial overlord.

The first seeds of Argentine independence were sown.

As time went by, the joy of defeating the British without anyone's help was replaced by an atmosphere of growing unease among Buenos Aires' movers and shakers, as the implications of their feat began to be felt. The criollos, always eager for more autonomy and power (as in other Spanish colonies), now had a battle-hardened military force of their own, while the peninsulares were absolutely terrified of it. The wartime alliance between Liniers and Álzaga cooled, with the criollos rallying behind the former and the peninsulares the latter. It was a a political environment ripe for intrigue, and it became even more so once news of the Dos de Mayo Uprising and the Abdications of Bayonne reached the shores of the Río de la Plata on August 1808.

These news were especially damaging for Liniers, since he was of French birth (his original name was Jacques de Liniers, before he changed it to his far more famous Spanish name). Despite issuing a statement in which he rejected Joseph Bonaparte's claim to the Spanish crown, similar to other acts done by fellow colonial rulers elsewhere, rumors spread that he was secretly planning otherwise. The governor of Montevideo, Francisco Javier de Elío, publicly challenged Liniers' authority by summoning a junta, without waiting for his approval, on September 21 (2). This development was watched closely by Martín de Álzaga and other prominent peninsulares in Buenos Aires, who, not unlike those in New Spain, sought to do away with Liniers and put someone more pliable to their interests. The criollos, on their part, still saw the viceroy as an ally, but they too were eager to shake up the status quo.

The situation became even more heated once word of the coup attempt in New Spain, and its consequences for the Europeans there, reached the ears of the porteños. The peninsulares' ongoing conspiracy radicalized - at first they intended to force Liniers to resign to give their takeover a veneer of legality, but now they wished to depose him outright, no matter the consequences (3). Some of the more ambitious criollos, increasingly frustrated with the viceroy's refusal to heed their repeated calls for the election of a junta, were busy plotting as well (4). Only dimly aware of each other's movements, both groups unwittingly picked the same date in which to put their plans in motion: January 1 1809.

A group of pro-independence criollos holding a secret meeting.

The fateful day came, and the peninsulares were the first to act: troops belonging to three regiments loyal to their cause, all made up of Spaniards, converged on Buenos Aires' main square (then called Plaza Victoria, later renamed Plaza de Enero (5)) shortly after sunrise. Once gathered, they advanced upon the fort that served as the viceroy's official residence, overpowering the guards and forcing Liniers to resign at gunpoint. Not long after, the cabildo (city council) of Buenos Aires, a stronghold of Álzaga's allies, issued a statement declaring the post of viceroy was vacant, and claiming to itself the authority to elect a substitute to serve on an interim basis. This news threw the Platine capital's criollos into a panic, and their most radical members, the military forces at their disposal bolstered by moderates fearing the peninsulares' imminent crackdown, launched their own uprising hours earlier than planned.

The alzaguistas, who expected to spend the rest of the day arresting their opponents and therefore cement their victory without a fight, were completely blindsided by the sudden appearance of the Legión Patricia's battle-hardened veterans, led by Cornelio Saavedra, on the streets. Backed by a substantial part of the populace, enraged by the news of Liniers' overthrow, the Patricios fought their way to the main square and entered the Fort of Buenos Aires, freeing the viceroy before his captors could deport him. The battle had radicalized the situation even further, however, and by the time the guns fell silent the crowds that had gathered on the Plaza Victoria were chanting the same slogan over and over: "¡Junta queremos!" ("We want a junta!" (6)).

Undoubtedly intimidated by the mob, and warned by Saavedra that any attempt to suppress it would lead to a mutiny, Liniers attempted to salvage whatever political power he could by calling a cabildo abierto (citizens' assembly), which was to convene on January 2. His ultimate intention was to buy time by letting the criollos, still rife with internal divisions, bicker among themselves on what to do while he and his allies came up with a plan to retake control of the situation.

The cabildo abierto convened on schedule, but it did so under an atmosphere so thick with tension it could be cut with a knife. The crowds from yesterday returned, their frenzied cheers replaced with an anxious silence as they waited for news, while within the cabildo itself armed guards were present in every session, ostensibly to maintain order but really to ensure the criollo party got its way in the negotiations to come. But not even the presence of these metaphorical swords of Damocles was enough for the cabildo's 251 members to reach a consensus on their first day of work: most agreed that the best course of action would be to create a junta, but what said junta would look like was a much thornier subject. The moderates, led by Saavedra and hoping to follow the example set by New Spain, argued a hypothetical junta ought to be presided by Liniers. Another, more radical faction, represented by men such as Mariano Moreno, Manuel Belgrano and Juan José Castelli, replied that the viceroy's very reticence on summoning a junta in the first place proved he could not be trusted with such a vital position - he had to be removed as well. A third group, made up of more conservative criollos and the few Europeans allowed to take part in the cabildo, said that, with the immediate threat posed by Álzaga and the peninsular regiments dealt with, all they had to do now was wait for further instructions from the Supreme Central Junta in Seville.

Ultimately, the only concrete measure the cabildo's members could agree on during their first day was a written statement reaffirming their loyalty to king Ferdinand VII. As they wasted precious time discussing minute details among themselves, just as Liniers had hoped, the viceroy sent a issued of messages to his closest allies not just in Buenos Aires itself, but more distant places as well. One particularly important message was to be sent to the province of Córdoba, instructing the authorities there to raise an army and march on Buenos Aires before the situation in the capital spiraled into an all out revolution (7). Little did he know, however, that the secretary he tasked with dispatching this letter was, in fact, a criollo sympathizer, who sent it to a completely different destination. It wouldn't be until early in the morning of January 3, hours before sunrise, that Liniers realized his mistake: his sleep was interrupted by armed men sent to arrest him.

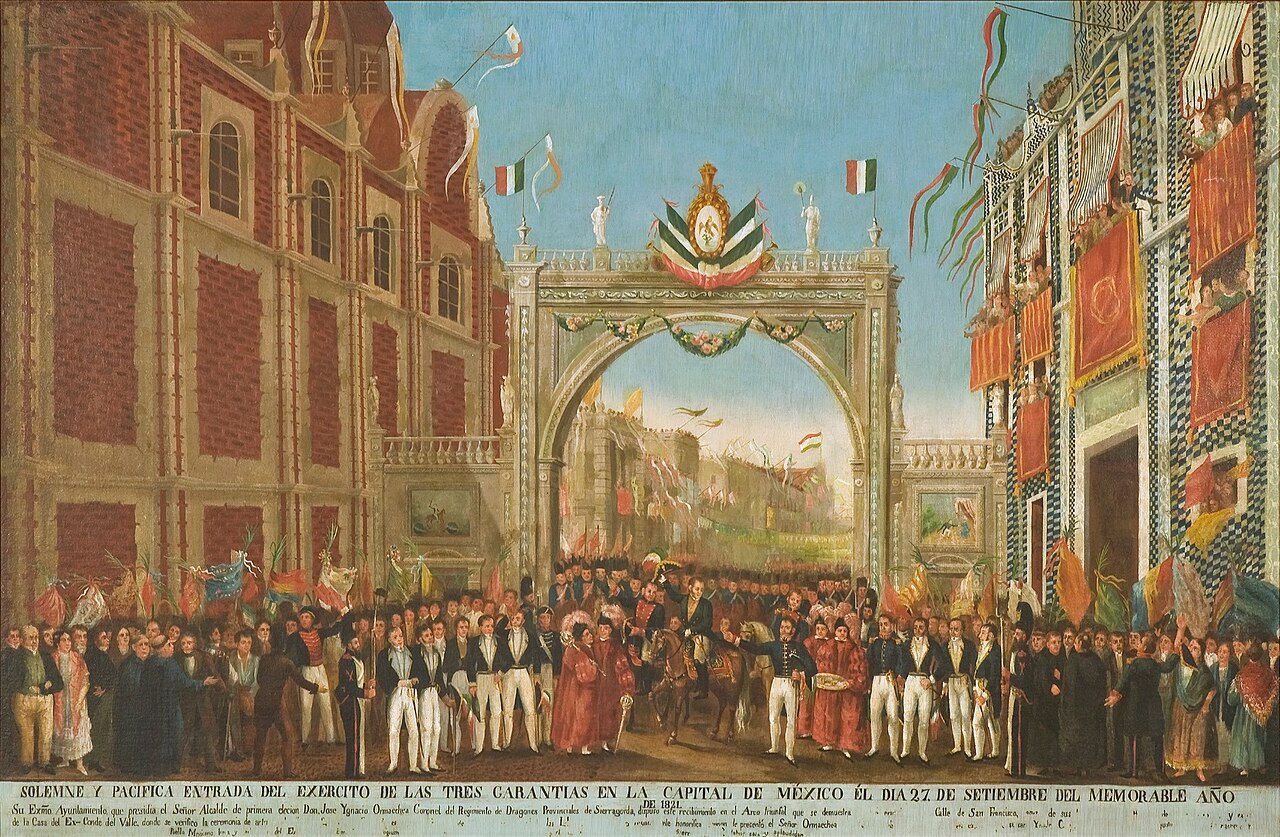

The January Revolution had begun.

With Liniers' treachery revealed, the cabildo abierto's second session was nothing like the first one: the radicals, joined by their moderate colleagues and vindicated on their belief not to trust him, passed a resolution declaring that Liniers was to be removed from the post of viceroy, effective immediately, and his deportation to Spain (8). With the elephant in the room out of the way, the next task was to deliberate on who would form the junta meant to govern in his place, a process which took several hours. In the end, the junta's composition was a compromise between the two main criollo factions: Saavedra, a moderate, was elected president, while Moreno became secretary of War and Government. The exact scenario Liniers sought to prevent became reality, and the conservatives could do nothing except watch helplessly.

The cabildo abierto voting on Liniers' dismissal and the junta meant to replace him.

The first priority of the Provisional Governing Junta of the Provinces of the Río de la Plata, as the revolutionary government named itself, was to cement the power it claimed to have over not only Buenos Aires, but all corners of the viceroyalty it claimed to represent. Messengers were dispatched to negotiate the allegiance of various cities and provinces to the revolutionary cause, while an army under Francisco Ortiz de Ocampo was sent to Córdoba to nip any potential royalist counterattacks from that direction in the bud. By February 1809 the situation had stabilized: most of the viceroyalty had pledged its allegiance to the revolutionaries, except for the province of Paraguay and, most troublingly, the Banda Oriental, still governed by Francisco Javier de Elío. This was a major thorn in the junta's side, since although Elío didn't have enough troops at his disposal to march on Buenos Aires, Montevideo provided a base from which the Spanish navy could launch devastating raids all over the River Plate.

Still, the Banda Oriental was rife with separatist sentiment, as shown by the successive victories scored by José Artigas, the revolutionary cause's main leader in the region, over the royalists. The local government's tax raises to fund its war against Buenos Aires were highly unpopular in the countryside, and Artigas' support snowballed until, by May 1809, Elío's authority was restricted to Montevideo itself. The revolutionaries' momentum stalled, however, since not only did Montevideo boast formidable defenses, which were strengthened after the British invasion, but the royalists' control of the sea made any siege worthless. Thus, Artigas' troops were forced to settle down for a very long siege (9).

The situation in Paraguay couldn't be more different, which made the events there all the more memorable. The population there was solidly behind the royalists, less due to genuine loyalty to the Spanish Crown and more out of a desire to become independent from Buenos Aires' authority. The revolutionary government sent an army of roughly 1.000 men under Manuel Belgrano, one of the governing junta's voting members, to subdue the province. After months of marching and enacting various administrative measures on the lands they crossed, Belgrano's army crossed the Paraná River at Campichuelo on May 17 1809, defeating a small Spanish force in the process. The rebels then marched towards Asunción, passing through several deserted villages along the way - a far cry from the reception they expected from the Paraguayan people.

It wouldn't be until June 20, more than a month later, that they came face to face with another enemy army, at Paraguarí. This was a much more formidable force than the one beaten at Campichuelo: 1.000 Spaniards, reinforced by 3.500 Paraguayans. With his men outnumbered by more than four to one, Belgrano attempted to parlay with his fellow South Americans against the Europeans, but these talks broke down once the Paraguayans made it clear they'd either have their current master or none at all. Despite the huge odds facing his army, Belgrano ordered a frontal attack on the morning of June 21, either putting faith in his troops' fervor or hoping to catch the royalists by surprise.

It was a success of almost unimaginable proportions. The royalists, not expecting to be attacked by an enemy they outnumbered by such a large margin, were completely surprised by the sight of rebel soldiers charging against their positions. Belgrano ordered for every soldier available to be sent into the fight, and the royalists' confusion gave way to panic as their attempts to regroup were hampered by the rebels' incessant hammer blows (10). By the time the Battle of Paraguarí ended, the royalist army had been scattered, and the Spanish governor of Paraguay, Bernardo de Velasco, was taken prisoner. The path to Asunción was open, and the press in Buenos Aires went haywire once it learned of the feat accomplished by Belgrano's army. But even these news, and the political aftermath of it (Belgrano was an ally of Mariano Moreno), would be pushed aside by another series of events which took place much further north: the revolution had spread to Peru.

Spain's southernmost colonies prior to the wars of independence. Upper Peru's provinces are in various shades of pink.

The source can be seen here.

The first Peruvian city to rise up against the Spanish was Chuquisaca, seat of the Real Audiencia of Charcas. The judges of the Audiencia, following the same rhetoric first used by Melchor de Talamantes and other separatists in New Spain (popular soverignty in the absence of the king), deposed the local governor and established a junta on May 25 1809. In Potosí, a city of great importance due to its silver mines, an attempt by intendant Francisco de Paula Sanz to prevent a mutiny by criollo officers backfired horribly, and he was forced to flee (11). La Paz followed suit not long after, with a junta led by colonel Pedro Murillo, and soon all of Upper Peru was up in arms against the Spanish. These rebels, who lacked a central authority for the time being (their rebellions were all separate, rather than part of a grander conspiracy), knew they needed all the help they could get if they were to survive the inevitable royalist counterattack. Thus, while they worked with one another to create an unified government and army as fast as possible, they also sent messengers to Buenos Aires. Unfortunately, the long distances, bad roads and difficult terrain along the way meant it would take a long time for their call for help to reach its destination, and even longer for reinforcements to arrive.

The rebels didn't know it yet, but the royalists, despite being practically next door, were not as strong as they feared. The viceroy of Peru, José Fernando de Abascal y Sousa, had a lot to deal with in his plate - besides the rebellion in Upper Peru, there were reports of varying levels of unrest elsewhere, particularly in Tacna, as well as an ongoing revolution in Quito (12). He was, as a result constantly bombarded with requests for help from several regions, many of them out of his jurisdiction, which made it difficult for him to focus his energy on a single area. Thus, it wouldn't be until September 1809, more than four months after the first spark of revolution set Upper Peru ablaze, that he managed to assemble an army of some 5.000 men (which would later grow to 7.000 after extra reinforcements, mainly native militias), led by José Manuel de Goyeneche.

Much time had passed by this point, more than enough for Buenos Aires to receive and answer the Peruvians' call for help. The army the Provisional Governing Junta sent to occupy Córdoba, still led by general Ocampo, was ordered to march northward with all due haste, and they reached their destination just in time to face the imminent royalist offensive (13). The combined Argentine and Peruvian armies had 8.500 troops in total, many of them hastily trained and poorly armed levies, and faced Goyeneche's forces near the town of Guaqui, just south of Lake Titicaca, on September 29 1809. The Battle of Guaqui was as costly as it was decisive: it stopped the Spanish advance into Upper Peru, but the rebel forces were so battered they were in no shape to follow up their victory. To make matters worse, it soon became clear the Argentines and Peruvians didn't see eye to eye, even if they had a common enemy.

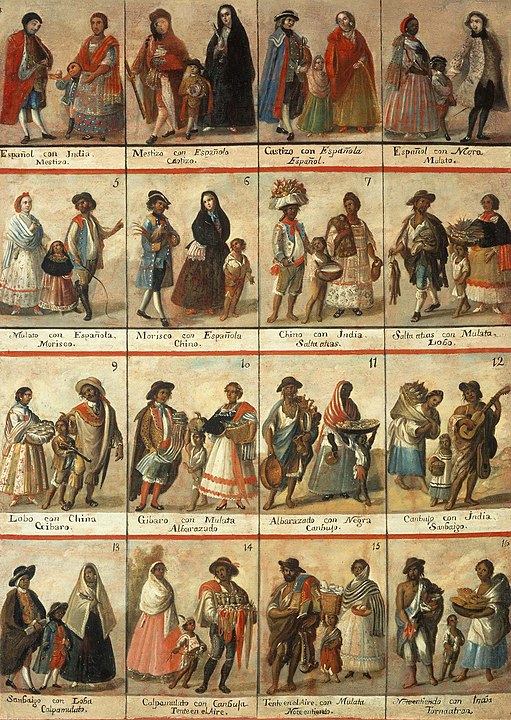

Upper Peru had been a part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata before the January Revolution, and the Provisional Governing Junta was eager to reassert Buenos Aires' rule over it, even if under a new banner, and Ocampo, as its highest local representative, made those intentions known. The Peruvian patriots, now united under La Paz's (and, therefore, Murillo's) leadership, balked at this, since they sought to reunite with the other half of Peru (the two regions had been ruled as one since Inca times, after all) and create a single, independent country capable of standing up to Madrid, Buenos Aires and anyone else (14). There was a racial factor as well: many porteños saw their Peruvian counterparts with disdain, due to their high degree of native ancestry. The latter, on their part, feared the troops of their so-called allies could end their newfound freedom if they became too strong, so they often withheld supplies and weapons from them, worsening the revolutionaries' logistics as a whole.

The war stagnated as a result, with no noticeable changes along the front line besides a rebellion in Tacna that brought said city into the revolutionary fold in June 1810 (15). Battle after battle was fought along the shores of Lake Titicaca, but even when the revolutionaries won they couldn't advance more than a few kilometers at a time - the royalists were just too heavily entrenched. Even then, however, the Spanish position was far from ideal: the stalemate in Peru left viceroy Abascal unable to detach troops from his army to help fellow royalists elsewhere, such as in Chile and New Granada, much to the relief of the pro-independence groups in those regions, at least for the time being (16). The gridlock lasted until April 1812, when truly earth-shattering news came from Spain: Ferdinand VII was back on his rightful throne.

Most important of all, however, was the news that Spain was no longer an absolute monarchy. This was thanks to the work of the Cortes, which, after months of deliberation between its deputies, who ranged from liberals to conservatives and everyone in between, crafted a constitution which, despite establishing Catholicism as the state's official religion and giving several rights to the king, made it clear his power wasn't limitless anymore (17). This was an unacceptable development to Abascal, a hardline supporter of absolutism, who first tried to suppress news of the new constitution and, after failing to do so, refused to apply its provisions in the areas under his control. This approach, though a blatant act of rebellion against the country the viceroy claimed to serve, met little, if any opposition from the officers in the royalist army: most of them were fellow absolutists, their convictions hardened by years of war against people who followed the same ideologies the constitution represented.

By the end of his tenure as viceroy of Peru, Abascal was an independent ruler in all but name.

But even if the army remained loyal, there was no shortage of people, many of whom already dissatisfied with Spanish rule, who saw Abascal's decision as the straw that broke the camel's back. One place where this sentiment was particularly prevalent was the city of Cusco, capital of the Inca Empire before its conquest by the Spanish almost three centuries prior. In the months that followed the arrival of news of the Spanish constitution, and Abascal's reaction to it, four brothers, José, Vicente, Mariano and Juan Angulo, began to plan an uprising, and slowly recruited allies among the members of the cabildo and the city garrison. One of the conspiracy's most important supporters was Mateo Pumacahua, a 72 year old Quechua kuraca (local noble) who, besides being one of the most prominent members of Peru's immense native population, also possessed a wealth of military experience - he played a critical role in the defeat of Túpac Amaru II more than thirty years before, and was recalled from retirement to lead native militias (a crucial component of the royalist forces) against the ongoing Peruvian rebellion. Pumacahua was so trusted by the Spanish authorities, thanks to his record, that he was appointed interim president of the Real Audiencia of Cusco.

Alas, that very trust meant the royalists were caught completely off guard when Cusco rose up against them, on August 9 1812. Troops loyal to the plotters took over the city in a matter of hours, and a junta of three members, Pumacahua the most senior of them, was proclaimed. The old general's call to arms was heeded by at least 20.000 people, the overwhelming majority of them Quechua natives. The symbolism of the colonizers losing control of the heart of the empire they conquered centuries ago was a profound one, and the rebel cusqueño administration followed up this success by sending an army, led by Pumacahua in person, to Arequipa, and dispatching a messenger to La Paz so as to begin talks with the revolutionary government in Upper Peru and its Argentine allies (18).

The revolutionary armies, bristling with tens of thousands of new recruits, began an offensive that swept its way through southern (lower) Peru from mid August onward, and, before Abascal and his subordinates could even begin to react, word reached Lima that yet another huge revolt had broken out behind the front, this time in Huánuco (19). With the war threatening to spill into the central Peruvian highlands, the royalists mounted a desperate attempt to stop the revolutionaries from combining with this latest rebellion at Huamanga, on October 12 1812. It was a crushing defeat, one that robbed the Spanish of their last army of note in Peru. Now there was nothing standing between the combined patriot forces and their ultimate goal: the city of Lima, whose capture was essential if the former colonies were to secure their freedom.

With his rule in Peru collapsing like a house of cards after the defeat at Huamanga, Abascal concluded he had no other option left but to flee. With the seas swarming with the vessels of pro-independence privateers like Thomas Cochrane and William Brown, the viceroy and his entourage had to evacuate Lima over land. Leaving the capital on October 27, Abascal made a beeline northward, towards New Granada, where a powerful Spanish army under Pablo Morillo had scored a series of victories against local pro-independence forces (20). The vanguard of the revolutionary army set off in pursuit, entering Lima just two days later under a surprisingly muted reception from local criollos, who were less than excited at the sight of thousands of armed natives on the streets.

The chase, immortalized in more books and movies than any reasonable person can bother to count, went on for weeks and several hundred kilometers, the pursuers almost catching up to their quarry on several occasions, but, ultimately, Abascal and his retinue were only one stroke of bad luck away from becoming prisoners or worse. And that was exactly what happened to them when they stopped at the city of Cajamarca on November 19. Unaware the commander of the local garrison was in cahoots with the revolutionaries, having been contacted by them a few days prior, Abascal and some of his secretaries went out to meet with him, only to be arrested on the spot. Horsemen from the Argentine contingent of the revolutionary army arrived hours later, followed later still by troops bearing the flags of the cusqueño and Upper Peruvian contingents.

The gig was up.

While the Capitulation of Cajamarca did not mark the end of the war with Spain - Morillo's army still had to be expelled from New Granada - it did seal Peru's independence from its colonial overlord. Celebrations broke out in multiple major cities all over the former Spanish colonies in South America once news of the capitulation reached them, from Caracas to Lima, La Paz, Santiago, Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Much like the liberation of Cusco back in August, Abascal's capture and subsequent surrender was profoundly symbolic to native Peruvians, since the viceroy was apprehended in the same place where Atahualpa, last ruler of the Inca Empire, was captured and later executed by the Spanish. With the war now moving outside of Peru's borders, the time had come to, much like in Mexico and later Argentina, summon a congress to decide the young nation's destiny. The task of organizing the elections for this congress, and governing the country until the deputies convened, was entrusted to a triune junta made up of José de la Mar (a former royalist general), Bernardo de Monteagudo (a lawyer and one of the intellectual leaders of the uprising in Chuquisaca) and, perhaps unsurprisingly, Mateo Pumacahua.

Left to right: José de la Mar, Bernardo de Monteagudo and Mateo Pumacahua, rulers of Peru from November 1812 until May 1813.

And what a task it was: three years of war had left Peru utterly devastated, with tens of thousands of civilians dead or maimed, and hundreds of thousands more forced to flee their homes. Mining and agricultural production ground to a halt, paralyzing the economy and threatening to cause a famine, while the collapse of the administrative structure set up by the Spanish led to a surge of banditry in the countryside. Fortunately, one thing the triumvirate didn't need to worry about was paying the army: Abascal's flight from Lima was made in such a hurry he was forced to leave a fabulous treasure, some estimating to be worth as much as US$208 million in today's money, behind (21). This unexpected gift was nothing short of a godsend to the revolutionary government, since several regiments of their army were on the verge of mutiny, and it also allowed their nascent state to pay off some of the debts it accumulated over the course of the war.

After almost seven months in power, the junta relinquished power to the First National Assembly, made up of 96 deputies, on May 25 1813. The date chosen for this act was no coincidence - it was the fourth anniversary of the rebellion in Chuquisaca, the event that began the Peruvian War of Independence. Still, much like other congresses of its kind, it took only a few sessions for any air of national unity to vanish, replaced by fierce regional and ideological divisions. The deputies from Lima and its surrounding area, many of whom were former royalists, were generally more conservative than those from the interior and Upper Peru, regions which, besides being hotbeds of anti-Spanish sentiment, also had a considerable native population. The main points of contention between the two factions were what form of government Peru should adopt and where the capital should be located.

The limeños, who wished to disturb the status quo as little as possible and thus salvage at least some of their privileges, predictably argued the capital should remain in their city, while many of their opponents, just as eager to have a bigger say in government, defended the idea of transferring Peru's capital to Cusco. The pro-Cusco party also called for the creation of a constitutional monarchy, one headed by a descendant of the Inca emperors, a proposal that had many supporters in the army. The limeños balked at this, ostensibly because they sought to follow the example set by other former Spanish colonies (other than Mexico) and establish a republic, but really because they didn't want to live under a native head of state. Other topics of fierce debate were the extent of the franchise and the continued existence of forced labour practices like the mit'a, a holdover from Inca times.

With the Spanish military ever further away with each defeat it suffered in New Granada, far beyond Peru's northern border, there was no unifying threat to force the First National Assembly to get its act together. The pro-Cusco party had a majority of the seats on paper, but their ranks were rife with internal divisions, with some deputies espousing far more radical proposals than others. A resolution establishing a constitutional monarchy was approved without much hassle, but all that did was shift the conversation to who would be given the crown: two candidates were considered, one of which, Juan Bautista Túpac Amaru, was in his sixties and had no heir, while the other, Dionisio Inca Yupanqui, was a leading advocate of native rights, making him unpalatable to many members of the criollo elite (22). The issue clung to the Assembly's neck like an albatross, and all kicking the can down the road did was worsen tensions between its members.

The First National Assembly.

Soon, the "Inca question" was brought up almost every time the Assembly convened to vote on whatever issue was brought to the table that day, each candidate's leading supporters not wasting a single opportunity to strengthen their cause among the deputies. All they accomplished was poisoning the well even further, with sessions officially devoted to discussing matters as "simple" as taxation devolving into shouting matches and fistfights on a few occasions. One infamous example happened on September 2 1813, when Francisco Antonio de Zela, a deputy from Tacna, attempted to present a bill which, if approved, would incorporate the native militias into the regular army (23). Instead, the bill was snatched from his hands and torn to shreds by another deputy, triggering a general brawl involving some 60 or so congresspeople that lasted for more than half an hour (24). Alas, Zela had a copy of the bill at his disposal just in case, and it was approved, under much tension, several hours later.

The Assembly's antics and purported lack of efficiency earned much frustration and scorn from the public, with crowds of hundreds or even thousands of people supporting this or that proposal congregating outside the main building of Lima's University of San Marcos, the place where the deputies were gathered. They were often met by other crowds who supported different policies, and the army had to step in multiple times, when their clashes escalated into vicious street battles with scores of casualties. Finally, on October 14 1813, a group of pro-Cusco army officers decided enough was enough. Led by the twenty-eight year old captain Agustín Gamarra, a mestizo from Cusco, 18 young officers entered the Assembly's main chamber right as the deputies were about to start debating the issue of the day. They stood on a spot reserved for the general public, seemingly intending to watch the upcoming legislative session unfold, and were immediately ordered to leave. The officers complied without saying a word, but not before scraping their sheathed swords against the floor on their way out (25).

No punishment was ever meted out against them.

The ruido de sables ("noise of sabers"), as this event became known, was a watershed moment in Peruvian history, one almost as important as the Chuquisaca Revolution and the various battles fought during the war of independence. It showed that there was another method with which one could get their way in politics, not through elections and debates, but through military might and all that entailed. Thoroughly intimidated by Gamarra's gesture and how he and his colleagues got away with it, the limeño deputies of the First National Assembly ceased all resistance to the laws proposed by their cusqueño adversaries. The Empire of Peru's first monarch would be Dionisio Inca Yupanqui, who, to the surprise of many, kept his original name instead of adopting a regnal one. All forms of forced labor were abolished, but no administrative body was established to enforce that. The right to vote was restricted to those who owned rural properties past a certain size, ensuring the countryside's political supremacy over the cities. That the capital stayed at Lima was but a fig leaf.

The cusqueño party got almost everything it wanted, but at a cost whose true extent wouldn't manifest itself until much later.

Dionisio Inca Yupanqui, first emperor of Peru. It was he who would have to deal with the eventual fallout of the ruido de sables

.

------------------

Notes:

(1) This is OTL. The colors were stored in the Santo Domingo Convent, in Buenos Aires, and are there to this day.

(2) This is OTL too. The junta was dissolved after the arrival of Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros, who replaced Liniers as viceroy of the Río de la Plata.

(3) IOTL they made a huge demonstration demanding Liniers' resignation instead of deposing him outright, probably to keep a veneer of legality, but this gave Saavedra and other

criollos enough time to fight back.

(4) A consequence of the butterflies born in Mexico.

(5) The

Plaza de Mayo's name commemorates the May Revolution, so if said revolution takes place in January, it only makes sense for it to be called

Plaza de Enero ITTL.

(6) Again, a consequence of the radicalization brought about by the events in Mexico.

(7) Liniers organized a counterrevolution IOTL, so he'd almost certainly try something similar in this scenario.

(8) Liniers' proven treachery, plus the lack of the controversy surrounding his execution, means his reputation will be far more negative ITTL.

(9) Montevideo resisted the Argentine revolutionaries for several years IOTL.

(10) According to what I found the Argentine army's initial assault was actually pretty successful IOTL, but their soldiers began to loot their enemies' supply stores, and their advance lost momentum. This allowed the Spanish and Paraguayans to launch a counterattack and defeat them.

(11) Sanz was able to keep control of Potosí IOTL, and this was a huge setback for the revolutionaries in Chuquisaca and La Paz.

(12) This revolution was suppressed by troops from Peru IOTL. Since Abascal already has his hands full with Upper Peru ITTL, he's forced to leave the

quiteños alone and pray their revolt doesn't spread too far.

(13) Ocampo didn't approve of Liniers' execution, so the junta in Buenos Aires replaced him with Juan José Castelli. Since said execution is butterflied away, he keeps his command.

(14) There were quite a few politicians in Peru and Bolivia who wanted to unite the two countries IOTL, albeit they disagreed on which of those countries should lead said union. It was this disagreement that tore the

Peru-Bolivian Confederation apart after just three years, since the Peruvians refused to live under Bolivian domination.

(15) This revolt broke out in 1811 IOTL, and was repressed.

(16) This means the royalists aren't able to reconquer Chile ITTL.

(17) Almost all of Spain was under French occupation when the Cortes first convened at Cádiz IOTL, so only a few regions could send their representatives. This meant the deputies there were overwhelmingly liberal, as was the constitution they created. Here the Supreme Central Junta doesn't dissolve until the war is won, so when the Cortes' composition is far more conservative compared to OTL. Ferdinand VII still hates the constitution because he's an absolutist jackass, but many people who would otherwise help him abrogate it are willing to give it a shot.

(18) The Cusco rebellion spread rapidly, but it was eventually suppressed IOTL. Pumacahua was executed, as were three of the four Angulo brothers.

(19) This revolt was quickly defeated IOTL.

(20) This is basically OTL, albeit a few years earlier since the French are kicked out of Spain sooner.

(21)

This treasure was meant be transported to Mexico City by sea IOTL, but the crew tasked with doing this went pirate and supposedly buried it in

Cocos Island.

(22) Dionisio served as a deputy in the Cortes of Cádiz IOTL.

(23) Zela led the 1811 Tacna revolt and was imprisoned following its suppression. He never regained his freedom, and eventually died in Panama.

(24) This tidbit was inspired by an incident that happened in Taiwan's parliament a few days ago, where a deputy grabbed some documents and ran away with them.

(25) This bit, meanwhile, was inspired by (and named after)

a similar event that happened in Chile IOTL.