Anyone have any ideas on what a Chinese state that was founded by a Hellenistic conqueror might call itself?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Legacy of the Three Alexanders

- Thread starter DominusNovus

- Start date

The Founding of The Ying Dynasty

Yalishanda, starting in 237 BC, sought to complete his conquest of the Zhou dynasty by defeating the remaining nominal vassal of Zhou, the southern state of Chu. By far the most powerful of the Warring States, Chu had been preparing for the invasion since Yalishanda had begun, 7 years prior. Its defenses had been bolstered all along its border, with impressive fortifications bolstering the impressive natural barrier that was the River Yangtze, protecting the southern of Chu.

Preparing for the invasion, Yalishanda formally deposed the final sovereign of Zhou, Han Wang, and declared a new dynasty, the Ying (鷹) Dynasty, so named after the hawk that symbolized his ancestry. He established his capital at the traditional site of Chengzhou, and held within his control all the formal regalia and insignia of a ruling sovereign of the realm. From this point, he began his assaults on the southern state.

However, the Chu proved far more resilient than their northern neighbors had been. They had certainly been bolstered by refugees of the fallen states, in particular, several leading generals, as well as even entire divisions of the former armies. This was not to say that all chose to flee to the Chu rather than serve under the new regime in the north, but that the number was not insignificant. Further, as the Chu had been prepared for the invasion, they were able to bleed the Ying forces in battle after battle, utilizing the strength of the terrain to their utmost advantage.

Chu continued to prove too large an opponent for Yalishanda's previously unblemished military record, and, after 2 years of inconclusive progress, his support began to diminish in the territories under his control. Revolts broke out across the land, and the next 2 years were spent in crushing those revolts while fending off counter-invasions by Chu, as the southern state sought to capitalize on the opportunity. From 233 BC onward, the relations between Ying and Chu would be marked by nothing so much as a military stalemate.

The time was not entirely marked by war, as philosophy and art flourished under Ying rule. Chu, in its efforts to maintain its borders against the superior numbers and wealth of Ying turned its land more and more towards the Legalist philosophy that had so dominated the former state of Qin. Ying, not constrained by a need to entirely militarize its society, became a patron of all the schools of philosophy in the land, including Legalism, Confucianism, Daoism, Mohism, as well as the countless minor schools. This served not only to attract philosophers to the north, but also to embed in society greater differences among the conquered population than among the conqueror.

The infrastructure of both the Ying in the north and the Chu in the south also saw great improvements, as both states continued to build up their fortifications, as well as the roads and canals within their territories. The economies of both states also blossomed, as the northern states were now under Ying rule and had a unified system of commerce stretching all the way to central Asia. The south also benefited, as despite the belligerency between the two realms, trade never stopped.

Thus, while Yalishanda had begun his life seeking to conquer the world or at least the entirety of the former Zhou state, he spend the last decades bogged down by the administration of his vast realm. He would live on until 221 BC, dying at age 62, never having been able to see his dream to completion.

Yalishanda, starting in 237 BC, sought to complete his conquest of the Zhou dynasty by defeating the remaining nominal vassal of Zhou, the southern state of Chu. By far the most powerful of the Warring States, Chu had been preparing for the invasion since Yalishanda had begun, 7 years prior. Its defenses had been bolstered all along its border, with impressive fortifications bolstering the impressive natural barrier that was the River Yangtze, protecting the southern of Chu.

Preparing for the invasion, Yalishanda formally deposed the final sovereign of Zhou, Han Wang, and declared a new dynasty, the Ying (鷹) Dynasty, so named after the hawk that symbolized his ancestry. He established his capital at the traditional site of Chengzhou, and held within his control all the formal regalia and insignia of a ruling sovereign of the realm. From this point, he began his assaults on the southern state.

However, the Chu proved far more resilient than their northern neighbors had been. They had certainly been bolstered by refugees of the fallen states, in particular, several leading generals, as well as even entire divisions of the former armies. This was not to say that all chose to flee to the Chu rather than serve under the new regime in the north, but that the number was not insignificant. Further, as the Chu had been prepared for the invasion, they were able to bleed the Ying forces in battle after battle, utilizing the strength of the terrain to their utmost advantage.

Chu continued to prove too large an opponent for Yalishanda's previously unblemished military record, and, after 2 years of inconclusive progress, his support began to diminish in the territories under his control. Revolts broke out across the land, and the next 2 years were spent in crushing those revolts while fending off counter-invasions by Chu, as the southern state sought to capitalize on the opportunity. From 233 BC onward, the relations between Ying and Chu would be marked by nothing so much as a military stalemate.

The time was not entirely marked by war, as philosophy and art flourished under Ying rule. Chu, in its efforts to maintain its borders against the superior numbers and wealth of Ying turned its land more and more towards the Legalist philosophy that had so dominated the former state of Qin. Ying, not constrained by a need to entirely militarize its society, became a patron of all the schools of philosophy in the land, including Legalism, Confucianism, Daoism, Mohism, as well as the countless minor schools. This served not only to attract philosophers to the north, but also to embed in society greater differences among the conquered population than among the conqueror.

The infrastructure of both the Ying in the north and the Chu in the south also saw great improvements, as both states continued to build up their fortifications, as well as the roads and canals within their territories. The economies of both states also blossomed, as the northern states were now under Ying rule and had a unified system of commerce stretching all the way to central Asia. The south also benefited, as despite the belligerency between the two realms, trade never stopped.

Thus, while Yalishanda had begun his life seeking to conquer the world or at least the entirety of the former Zhou state, he spend the last decades bogged down by the administration of his vast realm. He would live on until 221 BC, dying at age 62, never having been able to see his dream to completion.

Last edited:

Suceed

I hope this original and very interesting history ...

succeed in being ongoing

I hope this original and very interesting history ...

succeed in being ongoing

I just found this thread and must say that this is wonderful and I hope it's not done yet.

I hope this original and very interesting history ...

succeed in being ongoing

Thanks for the kind words, both of you. I definitely do intend to continue this further. I just have a few minor problems with the next few chapters:

- China and the rest of the far east are rather fanciful already (Yalishanda is loosely based off a fictional character from scifi), so they have to come back down to earth.

- Rome is going to be boring for awhile, sadly. Plenty of internal political instability, but, as far as their military exploits are concerned, its just the gradual pushing back of Gallic and Iberian tribes on the frontier. You know, the stuff that most history books gloss over when covering the Romans.

- India's... India. Far off and exotic, and with lots of hard-to-spell names. But, hey, at least its mostly historical at the moment, so that makes my life easier.

The only real action coming up soon is the two major successor states to Alexander, based in Egypt and Persia. They're going to bump heads, no matter what, and then there's Pyrrhus' little rump empire stretching across a good chunk of the Balkans.

It's Nice

It's Nice to see this interesting story going again.

I will always be interested in reading, good, stories based at least in part on Central Asia, China and combined my interest in the Hellenistic era.

This story is one of the few, really good being developed in the board

It's Nice to see this interesting story going again.

I will always be interested in reading, good, stories based at least in part on Central Asia, China and combined my interest in the Hellenistic era.

This story is one of the few, really good being developed in the board

Consolidations in the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was an unwieldy amalgamation of several different territories and political entities in the years following their victory over Pyrrhus. As the third decade of the century ended, the patchwork of governments was labyrinthine:

First, there was Rome itself and its outlying colonies scattered around the Italian Peninsula. Citizens of Rome, be they residents of the city itself or of the colonies held the highest rights within the commonwealth.

Beyond Rome, the various cities of the Latin League maintained s lower degree of citizenship for their inhabitants. They were tied the most closely to Rome, as evidenced by their right to elect a magistrate from among their own number, annually. The League had expanded significantly since the days in which they had won this right for themselves in the previous century, though genuinely Latin tribes continued to be in the majority. This growth was largely driven by the Romans thenselves, who sought to reward those cities in Italy that had served the Republic most reliably.

Near equal to the Latin League was the status of the Carthaginian Republic within he greater framework that was the Roman Republic of the era. While Carthage nominally held the same political rights that the Latin League as a whole, cultural and ethnic ties gave the Latins precedence. A further distinction was that the Latin League was composed of multiple cities that were equal, while Carthage was the main power amng its territories; all of the magistrates it would send to Rome were required to have served as the highest executive within the Carthaginian system, the Suffet. Though these Punic politicians were generally held in some suspicion, theur comparably high level of experience upon being sent to Rome would gradually earn them respect.

After Carthage were the various Italian allies, who wrre generally denied any polutical representation within Rome's system. However, they were genrally autonomous, with their only obligations to Rome itself usually being military support.

The final piece of the puzzle were the provinces, which numbered four at the time (Sicilia, Corsica Et Sardinia, Africa, and Hispania). These territories were largely subject to the whims the the Republic itself, and were regularly treated as sources of wealth to be mined for the benefit of the state and the governors thst served in their administration.

The Roman Republic was an unwieldy amalgamation of several different territories and political entities in the years following their victory over Pyrrhus. As the third decade of the century ended, the patchwork of governments was labyrinthine:

First, there was Rome itself and its outlying colonies scattered around the Italian Peninsula. Citizens of Rome, be they residents of the city itself or of the colonies held the highest rights within the commonwealth.

Beyond Rome, the various cities of the Latin League maintained s lower degree of citizenship for their inhabitants. They were tied the most closely to Rome, as evidenced by their right to elect a magistrate from among their own number, annually. The League had expanded significantly since the days in which they had won this right for themselves in the previous century, though genuinely Latin tribes continued to be in the majority. This growth was largely driven by the Romans thenselves, who sought to reward those cities in Italy that had served the Republic most reliably.

Near equal to the Latin League was the status of the Carthaginian Republic within he greater framework that was the Roman Republic of the era. While Carthage nominally held the same political rights that the Latin League as a whole, cultural and ethnic ties gave the Latins precedence. A further distinction was that the Latin League was composed of multiple cities that were equal, while Carthage was the main power amng its territories; all of the magistrates it would send to Rome were required to have served as the highest executive within the Carthaginian system, the Suffet. Though these Punic politicians were generally held in some suspicion, theur comparably high level of experience upon being sent to Rome would gradually earn them respect.

After Carthage were the various Italian allies, who wrre generally denied any polutical representation within Rome's system. However, they were genrally autonomous, with their only obligations to Rome itself usually being military support.

The final piece of the puzzle were the provinces, which numbered four at the time (Sicilia, Corsica Et Sardinia, Africa, and Hispania). These territories were largely subject to the whims the the Republic itself, and were regularly treated as sources of wealth to be mined for the benefit of the state and the governors thst served in their administration.

Last edited:

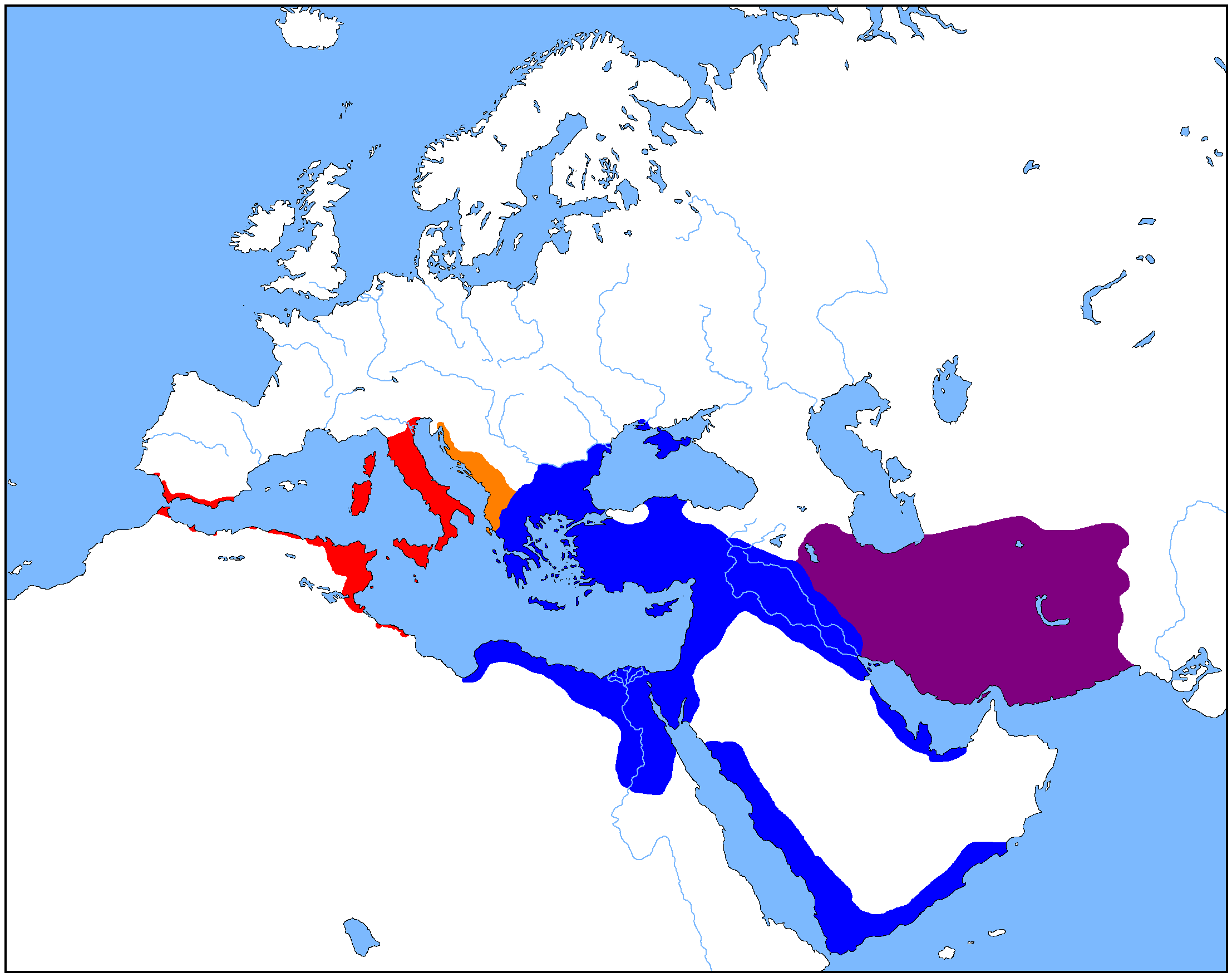

Want a (very) rough draft of a map of the Mediterranean after Pyrrhus' campaigns in Illyria? Of course you do. Take everything other than Roman territory with a grain of salt, but you should get the basic idea.

Hey guys, I'm going to re-do this timeline in the near future. If anyone has any particular suggestions or ideas on what could be done with it, let me know.

It's nice.

It's nice to see you back .

It's nice to see and know that you'll be back with updates on this story.

It's nice to see you back .

It's nice to see and know that you'll be back with updates on this story.

Share: