You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Dead Skunk

- Thread starter Lycaon pictus

- Start date

Juillet Lorrain (4)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

The uprisings in Italy, Poland and Saxony that began in July were widely considered “Bonapartist” by the Seventh Coalition — a claim too many historians have taken at face value. They were nothing of the sort. The writings of the rebel leaders themselves reveal that they did not trust Napoleon, and remembered too well his habit of redrawing the map of Europe to suit his fancy. Still less, however, did they wish to be conscripted into the ranks of his enemies.

Nonetheless, they posed a serious distraction for the Coalition. Austria was forced to send the armies of Frimont and Bianchi into Italy. Russia diverted the corps commanded by General Wurttemberg (not to be confused with the Prince Wurttemberg who served Austria) and the Reserve Cavalry to deal with the Polish rebellion.

And Prussia was on the brink of destruction. The rebellion in Posen began July 9 — the very day the city received word of Velaine — and spread through the countryside and into Upper Silesia, with smaller uprisings in Stargard and Allenstein and ethnic violence in Danzig, Königsberg and Breslau. Meanwhile, Frederick Augustus I took this opportunity to attempt to shake off Prussian control of Saxony.

Frederick William III called for conscripts from Westphalia and the other relatively peaceful western parts of Prussia, and the westerners responded. In Münster, Cologne and the towns of the Ruhr, over a dozen new volunteer regiments were formed. They organized themselves, trained as quickly as they could, were armed… and then they waited. They did not actually mutiny, but they kept finding reasons not to go east where they were urgently needed. In this, they were assisted by the city and provincial governments, who used every trick at their disposal (in one case, “arresting” the officers of a regiment and holding over a hundred soldiers as witnesses) to keep them nearby. The real reason, of course, was that with France still a threat just across the Rhine, they had no intention of abandoning their homes in order to assist the Junkers in suppressing Poles, or of helping to beat down the presumptuous Saxon king. Last year, most of these men hadn’t even been Prussians.

Under normal circumstances, this in itself would have constituted a rebellion, and one to be put down by force. But the king knew that if he tried, he would face a real rebellion in the west — which, at this point, would most likely end Prussia once and for all…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

Nonetheless, they posed a serious distraction for the Coalition. Austria was forced to send the armies of Frimont and Bianchi into Italy. Russia diverted the corps commanded by General Wurttemberg (not to be confused with the Prince Wurttemberg who served Austria) and the Reserve Cavalry to deal with the Polish rebellion.

And Prussia was on the brink of destruction. The rebellion in Posen began July 9 — the very day the city received word of Velaine — and spread through the countryside and into Upper Silesia, with smaller uprisings in Stargard and Allenstein and ethnic violence in Danzig, Königsberg and Breslau. Meanwhile, Frederick Augustus I took this opportunity to attempt to shake off Prussian control of Saxony.

Frederick William III called for conscripts from Westphalia and the other relatively peaceful western parts of Prussia, and the westerners responded. In Münster, Cologne and the towns of the Ruhr, over a dozen new volunteer regiments were formed. They organized themselves, trained as quickly as they could, were armed… and then they waited. They did not actually mutiny, but they kept finding reasons not to go east where they were urgently needed. In this, they were assisted by the city and provincial governments, who used every trick at their disposal (in one case, “arresting” the officers of a regiment and holding over a hundred soldiers as witnesses) to keep them nearby. The real reason, of course, was that with France still a threat just across the Rhine, they had no intention of abandoning their homes in order to assist the Junkers in suppressing Poles, or of helping to beat down the presumptuous Saxon king. Last year, most of these men hadn’t even been Prussians.

Under normal circumstances, this in itself would have constituted a rebellion, and one to be put down by force. But the king knew that if he tried, he would face a real rebellion in the west — which, at this point, would most likely end Prussia once and for all…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

The uprisings in Italy, Poland and Saxony that began in July were widely considered “Bonapartist” by the Seventh Coalition — a claim too many historians have taken at face value. They were nothing of the sort. The writings of the rebel leaders themselves reveal that they did not trust Napoleon, and remembered too well his habit of redrawing the map of Europe to suit his fancy. Still less, however, did they wish to be conscripted into the ranks of his enemies.

Nonetheless, they posed a serious distraction for the Coalition. Austria was forced to send the armies of Frimont and Bianchi into Italy. Russia diverted the corps commanded by General Wurttemberg (not to be confused with the Prince Wurttemberg who served Austria) and the Reserve Cavalry to deal with the Polish rebellion.

And Prussia was on the brink of destruction. The rebellion in Posen began July 9 — the very day the city received word of Velaine — and spread through the countryside and into Upper Silesia, with smaller uprisings in Stargard and Allenstein and ethnic violence in Danzig, Königsberg and Breslau. Meanwhile, Frederick Augustus I took this opportunity to attempt to shake off Prussian control of Saxony.

Frederick William III called for conscripts from Westphalia and the other relatively peaceful western parts of Prussia, and the westerners responded. In Münster, Cologne and the towns of the Ruhr, over a dozen new volunteer regiments were formed. They organized themselves, trained as quickly as they could, were armed… and then they waited. They did not actually mutiny, but they kept finding reasons not to go east where they were urgently needed. In this, they were assisted by the city and provincial governments, who used every trick at their disposal (in one case, “arresting” the officers of a regiment and holding over a hundred soldiers as witnesses) to keep them nearby. The real reason, of course, was that with France still a threat just across the Rhine, they had no intention of abandoning their homes in order to assist the Junkers in suppressing Poles, or of helping to beat down the presumptuous Saxon king. Last year, most of these men hadn’t even been Prussians.

Under normal circumstances, this in itself would have constituted a rebellion, and one to be put down by force. But the king knew that if he tried, he would face a real rebellion in the west — which, at this point, would most likely end Prussia once and for all…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

Frederick Augustus had better be trying to get Metternich and perhaps the Bavarians for good measure in his corner if he wants to make this stick. And am I sniffing an independent principality of some sort in the offing potentially centred on J-K-B and Westfalen perhaps under a separate Hohenzollern or Wittlesbach prince.

Lycaon pictus

Sounds like there's the basis here for a temporary patch on things with Napoleon allowing the continental powers to crush their assorted rebellions while they have a deal with him, probably including the annexation of Belgium.

That would however be a short term thing as no one trusts him and he's unlikely to be able to avoid returning to the battlefield. Not to mention it still leaves him at war with his greatest enemy in a position somewhat more favourable to Britain. [No continental blockade so we can trade freely while France will be locked down tight in terms of coastal traffic. Not to mention I'm not sure if the French colonies would have been returned yet but if they have how long would they last?]

There would then be the question of Hanover but if Boney tries to attack that it would likely trigger another continental coalition against him.

All-in-all Europe is probably going to have another couple of years of conflict and destruction.

Steve

Sounds like there's the basis here for a temporary patch on things with Napoleon allowing the continental powers to crush their assorted rebellions while they have a deal with him, probably including the annexation of Belgium.

That would however be a short term thing as no one trusts him and he's unlikely to be able to avoid returning to the battlefield. Not to mention it still leaves him at war with his greatest enemy in a position somewhat more favourable to Britain. [No continental blockade so we can trade freely while France will be locked down tight in terms of coastal traffic. Not to mention I'm not sure if the French colonies would have been returned yet but if they have how long would they last?]

There would then be the question of Hanover but if Boney tries to attack that it would likely trigger another continental coalition against him.

All-in-all Europe is probably going to have another couple of years of conflict and destruction.

Steve

Lycaon pictus

Donor

Not to mention I'm not sure if the French colonies would have been returned yet but if they have how long would they last?

Here's a question I can answer without spoiling any of the main events.

France is definitely going to lose all its colonies in the Americas — St. Pierre and Miquelon, the Caribbean islands and French Guiana, which I haven't decided whether to rename British East Guiana or British Cayenne.

Haiti will be nominally independent but economically dominated by the British Empire. The British are not comfortable with an independent nation of ex-slaves, but they're not crazy enough to try and conquer it. They also don't see any reason why the French should get free money out of it. So there will be no 150-million-gold-franc reparations to France. (Haiti still has 99 problems, but this ain't one.)

Here's a question I can answer without spoiling any of the main events.

France is definitely going to lose all its colonies in the Americas — St. Pierre and Miquelon, the Caribbean islands and French Guiana, which I haven't decided whether to rename British East Guiana or British Cayenne.

Haiti will be nominally independent but economically dominated by the British Empire. The British are not comfortable with an independent nation of ex-slaves, but they're not crazy enough to try and conquer it. They also don't see any reason why the French should get free money out of it. So there will be no 150-million-gold-franc reparations to France. (Haiti still has 99 problems, but this ain't one.)

Lycaon pictus

Of those, in the medium to long term, the northern islands will probably be the most important as it will presumably also mean they lose their access to the Grand Banks fisheries.

The Caribbean islands will be economically important in the near term as they are major producers of sugar and other plantation items. However once slavery is banned their economic value, like those of the OTL British islands, largely evaporates. [This presumes that possession of them doesn't prevent the victory of the anti-slavery movement, but at this late stage I would say that is still pretty certain].

Haiti could make for a useful ally, especially once Britain bans slavery.

Elsewhere in the world the French are already fairly restricted at this point. They have Senegal and possibly a couple of W African outposts but, presuming the earlier events have gone as OTL Britain has Mauritius and their Indian pockets are purely financial and can be fairly quickly liberated.

What could be important is what happens to the Dutch colonies if the Netherlands are conquered by Napoleon. Britain should be able to retake them again, or the local colonial authorities might support a Dutch government in exile in London, which would save the hassle of occupying them again.

I doubt Spain would be attacked as I suspect even Napoleon would have learnt not to stick his neck in that noose again.

The only other thing, but I suspect its unlikely is if the Americans, seeing a new war in Europe try reopening their war.

Steve

Juillet Lorrain (5)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

The next ten days showed why the Juillet Lorrain is often called “the bear-baiting” or “the boar hunt” — the various Coalition armies harried l’Armée du Nord (now well out of the north) constantly, chasing it here and there through western Alsace and eastern Lorraine, engaging it wherever possible but never allowing themselves into a position where they could be surrounded or routed.

Meanwhile, fresh regiments from Austria, Russia and the smaller German states kept coming across the Rhine, swelling the Coalition’s ranks. French reinforcements were collecting in the city of Nancy, which, with the aid of officers who had served under Davout at Hamburg, was being readied to stand a long siege, if necessary.

Of course, Napoleon wasn’t the only one who needed new recruits. The armies guarding the border with Spain desperately needed reinforcement as well. In the Vendée, General Lamarque was building up his forces for a move north into Belgium. The French, who had to fight everywhere, were outnumbered everywhere.

Then, on July 15, Napoleon turned east, hoping to break the siege of Strasbourg…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

Meanwhile, fresh regiments from Austria, Russia and the smaller German states kept coming across the Rhine, swelling the Coalition’s ranks. French reinforcements were collecting in the city of Nancy, which, with the aid of officers who had served under Davout at Hamburg, was being readied to stand a long siege, if necessary.

Of course, Napoleon wasn’t the only one who needed new recruits. The armies guarding the border with Spain desperately needed reinforcement as well. In the Vendée, General Lamarque was building up his forces for a move north into Belgium. The French, who had to fight everywhere, were outnumbered everywhere.

Then, on July 15, Napoleon turned east, hoping to break the siege of Strasbourg…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

Does this mean that Sweden will keep Guadelope? It was given to Sweden by the British 1812, and sold back to France for 24 million franc in 1815 to cover war debts - but if Napoleon rules longer, it will most likely not be sold to France. Perhaps to the British?

von Adler

Interesting, I had never heard of that before. Thanks for that.

However, if Wiki is right

By the Anglo-Swedish alliance of 3 March 1813, it was ceded to Sweden for a brief period of 15 months. The British administration continued in place and British governors continued to govern the Island.[5] By the Treaty of Paris of 1814 Sweden ceded Guadeloupe once more to France

It had already been given back to France in 1814. Whether French forces had actually arrived in any strength and who they feel loyalty to, here and elsewhere could be interesting questions.

Steve

Lycaon pictus

Donor

Perhaps to the British?

Definitely to the British. The Caribbean will be a British lake for at least the next few decades. France is out, but other countries that own islands there, like Spain, will be permitted to keep them if they are good.

(stevep, I hadn't heard about the thing with Sweden either.)

Juillet Lorrain (6)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

Work! for the power outage cometh, wherein no man can work.

If anything ever proved that “time and chance happeneth to all,” it was the engagement of July 17 along the banks of the Zorn. Prince William of Württemberg, who had just endured a shameful defeat at La Suffel, won a battle against Napoleon himself.

Three things made this possible. First, Napoleon was unaware of the size of the army the prince commanded. The Third and Reserve Corps — at this point, a force of over 90,000 men, easily the equal of Napoleon’s own — surrounded the city of Strasbourg and the army of General Rapp. (Ordinarily, devoting two army corps to trap twenty thousand men would have been foolish — but if there was one thing the Coalition had to spare, it was manpower.) Second, Württemberg's men were relatively fresh, having remained in place for the last few weeks while Napoleon's army had been run ragged.

Third, Württemberg abandoned the siege, mobilized his army and attacked first. In a letter to his father, the giant King Frederick, he explains this decision thus: “Behind me was the Corsican, who had yet to be defeated this year. Before me was Rapp, who had already bested me once. I confess that in that hour I saw no hope of victory. Determined to meet my fate directly, I turned and set forth to engage the stronger enemy. The Lord in His mercy forgave my despair and granted me the triumph I had not looked for.”

Judging by his deployments, Napoleon had not looked for this attack to take place. In the sudden attack, the emperor’s heavy cavalry was routed and Marshal Grouchy was killed, along with some 5,000 Frenchmen. It was all Napoleon could do to keep the fighting retreat from turning into a general rout. (In this, he was aided by Prince William himself. Rather than pursuing the defeated French into the Vosges, he turned around to deal with the force at Strasbourg, only to find that Rapp and his army had slipped out to the southwest.)

Meanwhile, the other armies — Russian, Austrian and German — were closing in. Their aim was to prevent Napoleon from reaching Nancy at all costs. To this end, one of them would have to get in his way.

But as luck would have it, the first fighting force that interposed itself between the emperor and his shelter was the worst possible one for the job. After the fact, none of the Coalition generals would admit to having dispatched the Royal Danish Auxiliary Corps on this particular mission — and, indeed, they may have been there entirely by chance. But the Danes, already bitter over the ill-treatment their nation had received at the hands of the Royal Navy and the delegates to Vienna, were most reluctant allies to begin with. Now they were being asked, in effect, to stand and die in place so that some other power should have the glory of triumphing over Napoleon.

The result? The entire army “surrendered” almost without firing a shot. In fact, an unknown but significant number of them joined the French army, while others allowed themselves to be employed guarding the numerous Russian and Prussian prisoners of war…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

If anything ever proved that “time and chance happeneth to all,” it was the engagement of July 17 along the banks of the Zorn. Prince William of Württemberg, who had just endured a shameful defeat at La Suffel, won a battle against Napoleon himself.

Three things made this possible. First, Napoleon was unaware of the size of the army the prince commanded. The Third and Reserve Corps — at this point, a force of over 90,000 men, easily the equal of Napoleon’s own — surrounded the city of Strasbourg and the army of General Rapp. (Ordinarily, devoting two army corps to trap twenty thousand men would have been foolish — but if there was one thing the Coalition had to spare, it was manpower.) Second, Württemberg's men were relatively fresh, having remained in place for the last few weeks while Napoleon's army had been run ragged.

Third, Württemberg abandoned the siege, mobilized his army and attacked first. In a letter to his father, the giant King Frederick, he explains this decision thus: “Behind me was the Corsican, who had yet to be defeated this year. Before me was Rapp, who had already bested me once. I confess that in that hour I saw no hope of victory. Determined to meet my fate directly, I turned and set forth to engage the stronger enemy. The Lord in His mercy forgave my despair and granted me the triumph I had not looked for.”

Judging by his deployments, Napoleon had not looked for this attack to take place. In the sudden attack, the emperor’s heavy cavalry was routed and Marshal Grouchy was killed, along with some 5,000 Frenchmen. It was all Napoleon could do to keep the fighting retreat from turning into a general rout. (In this, he was aided by Prince William himself. Rather than pursuing the defeated French into the Vosges, he turned around to deal with the force at Strasbourg, only to find that Rapp and his army had slipped out to the southwest.)

Meanwhile, the other armies — Russian, Austrian and German — were closing in. Their aim was to prevent Napoleon from reaching Nancy at all costs. To this end, one of them would have to get in his way.

But as luck would have it, the first fighting force that interposed itself between the emperor and his shelter was the worst possible one for the job. After the fact, none of the Coalition generals would admit to having dispatched the Royal Danish Auxiliary Corps on this particular mission — and, indeed, they may have been there entirely by chance. But the Danes, already bitter over the ill-treatment their nation had received at the hands of the Royal Navy and the delegates to Vienna, were most reluctant allies to begin with. Now they were being asked, in effect, to stand and die in place so that some other power should have the glory of triumphing over Napoleon.

The result? The entire army “surrendered” almost without firing a shot. In fact, an unknown but significant number of them joined the French army, while others allowed themselves to be employed guarding the numerous Russian and Prussian prisoners of war…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

Last edited:

But Everyone Knows it as Nancy (1)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

Napoleon reached Nancy on July 20 and immediately began transferring his tired and wounded soldiers behind the defensive lines. But it was clear he was preparing for something far more complicated than a simple siege.

Vandamme was placed in charge of 100,000 men and sent to the heights north of the city on either side of the Meurthe. Meanwhile, Ney was given command of all the light cavalry that could be found, and was sent east. His task was to execute guerrilla raids against the supply lines of the giant Coalition army. When pursued, he would retreat into the hill country of the Vosges.

Napoleon himself remained in the center of the city, behind the defensive lines and the 150-meter moat of the Meurthe. At Vienna, the nations of Europe had essentially declared war on one man. If they wanted him, they could come and take him.

They obliged. The Battle of Nancy was nearly as large in scope as that of Leipzig, lasted considerably longer and was much bloodier. Every part of it — “the Sugarloaf,” “Bloody Saint-Genevieve,” “the Dreadful Crossing” — has taken on a mythic quality among enthusiasts of military history. Many historians have suggested that the Coalition made a mistake in not bypassing the city and heading for Paris.

But this was not an option. Davout had not been idle over the last month. Paris, by now, had its own ring of defenses. Davout was quoted as saying that “if they liked Hamburg, they are going to love Paris.” The Austrian and Russian generals had no desire to be trapped at the end of a long supply line between Davout’s lines and Napoleon’s men.

So they attacked directly — and over the course of the next three weeks, Nancy became a byword for manhood and valour throughout the Western world.

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

Vandamme was placed in charge of 100,000 men and sent to the heights north of the city on either side of the Meurthe. Meanwhile, Ney was given command of all the light cavalry that could be found, and was sent east. His task was to execute guerrilla raids against the supply lines of the giant Coalition army. When pursued, he would retreat into the hill country of the Vosges.

Napoleon himself remained in the center of the city, behind the defensive lines and the 150-meter moat of the Meurthe. At Vienna, the nations of Europe had essentially declared war on one man. If they wanted him, they could come and take him.

They obliged. The Battle of Nancy was nearly as large in scope as that of Leipzig, lasted considerably longer and was much bloodier. Every part of it — “the Sugarloaf,” “Bloody Saint-Genevieve,” “the Dreadful Crossing” — has taken on a mythic quality among enthusiasts of military history. Many historians have suggested that the Coalition made a mistake in not bypassing the city and heading for Paris.

But this was not an option. Davout had not been idle over the last month. Paris, by now, had its own ring of defenses. Davout was quoted as saying that “if they liked Hamburg, they are going to love Paris.” The Austrian and Russian generals had no desire to be trapped at the end of a long supply line between Davout’s lines and Napoleon’s men.

So they attacked directly — and over the course of the next three weeks, Nancy became a byword for manhood and valour throughout the Western world.

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

But Everyone Knows it as Nancy (2)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

Even a genius is limited by the tools he is given to work with. Napoleon had turned the city of Nancy and environs into a trap to hold half a million men, but the trap would not close unless he himself were in the middle of it. More importantly, the emperor’s attention was devoted firstly to the day-to-day shifts in the tactical situation of the battle, as the Austrian and Russian princes and their hirelings pushed deeper into the city, driving the French defenders back block by block. Even before then, of course (arguably, since he left Paris) his thoughts had been preoccupied with the problem of safeguarding his people rather than the problem of ruling them.

What this meant for France as a whole during this fateful summer was that the governing of the realm was chiefly in the hands of Parliament. The irony in this, of course, is that Napoleon had never wanted to put the constitutional reforms of 1815, under which the Parliament was constituted, into effect until the campaign was over. Moreover, he disliked and distrusted the parliament that had been elected in the plebiscite of June 1; in fact, his first desire had been to dismiss it, although he had allowed himself on this occasion to be convinced that a whim of his was not practicable.

Nor did Parliament hold any great trust in him. Perhaps a hundred of the Parliamentarians were of the Parti de Bonaparte, whose only platform was personal fidelity and trust in him. There was also a smaller group from the Jacobin Party. Militantly anticlerical, fiercely egalitarian and strongest in the cities, these forerunners of the modern Elmarists regretted not one drop of blood shed in the Terror. They, too, were loyal to Napoleon, although he hardly knew what to do with their loyalty.

But five out of six Parliamentarians were of the Liberal Party, and followed La Fayette and Lanjuinais in regarding Napoleon as a threat to the liberties of the French people. As Jean-Baptiste Say put it, “The Legislative Body, an amalgamation of parties and representatives of every epoch of the Revolution, while attached to the institutions of the Revolution and despising the prejudices and ineptitude of the Bourbons, is yet filled with mistrust, fear and horror of the tyranny of Napoleon.” (Ironically, the situation would have been a good deal worse had the royalists not chosen to absent themselves from the plebiscite, waiting instead for their king to return in the baggage train of another conquering army.)

Even his ministers, however loyal they remained in public, had begun to despair of him. Caulaincourt, his foreign minister and a long-standing friend and loyalist, privately believed him mad and suspected that his promises of French liberty would hold good only “until he is on his feet and returns to his old ways.” Fouché, whom Napoleon distrusted but on whom he was forced to rely as one of the pillars of his rule, was of course quite indifferent to liberty; yet he believed that the Emperor was doomed to be overthrown in four months at best, and it is rumored that he was plotting with the royalists until word of Velaine reached Paris.

But all this was no insurmountable obstacle. None of the Liberals had ever denounced Napoleon so feverishly as Benjamin Constant, who had called the French emperor “this madman dyed with our blood” and fled to Nantes to avoid having to serve him. But once Constant had been captured and returned to Paris, Napoleon had won him over almost instantly and set him to work on the new constitution. If he could win over Constant, he could surely win over the Deputies and Peers.

The magic of his persuasion was even beginning to work on the war-weary people of France itself. In this he was aided unwittingly by the Prussians— or rather, their newspapers. The Allgemeine Zeitung proclaimed, “We were wrong to show the French any consideration whatsoever. We should have wiped them all out… the whole French nation must be outlawed.” Not to be outdone, the Mercure du Rhin opined that “We must exterminate them; kill them like mad dogs.” Napoleon had only to order these editorials reprinted in the Moniteur to convince much of the public that such sentiments represented the general mood of the Seventh Coalition, and that the French Emperor was the nation’s last hope. (One American historian, Charles Cerniglia, has proposed that Napoleon may have learned this from studying British actions at New Orleans in the wake of General Keane’s capture of that city. In the absence of evidence, this remains mere conjecture.)[1]

In any event, there was no help for it. If the emperor won, he would return and rule, and they would be lucky if he allowed the new parliament to remain in session at all. (And after the glorious triumphs of Velaine and Mayence, who would say he did not have the right?) Whereas if he failed, then, as Fouché put it after the setback at the Zorn, “the crowned heads of Europe would spill every last drop of Christian blood to return Louis the Pig’s bloated arse to his throne and Marie Antoinette’s empty head to her neck.” Thus, the Liberals of Parliament judged their fate to be closely tied to that of Napoleon, whether they wished it so or not.

In the meantime, there was a nation to be governed, which Napoleon could not do from the battlefield. Taxes had to be gathered, conscripts brought to the training fields, supplies procured. Davout’s efforts at fortifying Paris and building camps south and west of the city needed to be supported.

And so a strange political partnership developed. Lanjuinais and his vice-president, Jacques-Charles Dupont de l’Eure, were the public face of the new regime, reading Napoleon’s dispatches aloud in the Champs-Élysées. Meanwhile, Carnot was turning his engineer’s brain to the task of building the Liberal Party into a system for finding reliable men, securing their loyalty and installing them in office. The Moniteur became the Liberal Party's official house organ.

The Party undertook other tasks as well. Wherever opposition (royalist or simply antiwar) threatened to interfere with the purposes of the government, the Liberals unleashed the fédérés, groups of radical workingmen whom Napoleon had despised but whom Carnot was only too pleased to arm and train for the suppression of dissent. (Most of the fédérés were Jacobite rather than Liberal, but few proved unwilling to compromise their principles in exchange for the chance to serve their nation and their emperor.)

If the fédérés were the Party’s naked fist, Fouché and his secret police were its hidden dagger. A born conspirator, Fouché proved a genius at finding royalist plots and bringing them to light — or, when he judged it more suitable, disposing of them in the darkness.

At this point, the Liberal Party’s writ hardly ran in the south or the smaller towns, where royalist sentiment was still a force to be reckoned with. Nonetheless, by the end of July, the two chambers of Parliament and the Liberal Party had become as effective a machine of governance as any in Europe…

Jean-Michel Noailles, The Liberal Party and the Making of Modern France (Eng. trans)

***

[1] Actually, Napoleon did this IOTL.

What this meant for France as a whole during this fateful summer was that the governing of the realm was chiefly in the hands of Parliament. The irony in this, of course, is that Napoleon had never wanted to put the constitutional reforms of 1815, under which the Parliament was constituted, into effect until the campaign was over. Moreover, he disliked and distrusted the parliament that had been elected in the plebiscite of June 1; in fact, his first desire had been to dismiss it, although he had allowed himself on this occasion to be convinced that a whim of his was not practicable.

Nor did Parliament hold any great trust in him. Perhaps a hundred of the Parliamentarians were of the Parti de Bonaparte, whose only platform was personal fidelity and trust in him. There was also a smaller group from the Jacobin Party. Militantly anticlerical, fiercely egalitarian and strongest in the cities, these forerunners of the modern Elmarists regretted not one drop of blood shed in the Terror. They, too, were loyal to Napoleon, although he hardly knew what to do with their loyalty.

But five out of six Parliamentarians were of the Liberal Party, and followed La Fayette and Lanjuinais in regarding Napoleon as a threat to the liberties of the French people. As Jean-Baptiste Say put it, “The Legislative Body, an amalgamation of parties and representatives of every epoch of the Revolution, while attached to the institutions of the Revolution and despising the prejudices and ineptitude of the Bourbons, is yet filled with mistrust, fear and horror of the tyranny of Napoleon.” (Ironically, the situation would have been a good deal worse had the royalists not chosen to absent themselves from the plebiscite, waiting instead for their king to return in the baggage train of another conquering army.)

Even his ministers, however loyal they remained in public, had begun to despair of him. Caulaincourt, his foreign minister and a long-standing friend and loyalist, privately believed him mad and suspected that his promises of French liberty would hold good only “until he is on his feet and returns to his old ways.” Fouché, whom Napoleon distrusted but on whom he was forced to rely as one of the pillars of his rule, was of course quite indifferent to liberty; yet he believed that the Emperor was doomed to be overthrown in four months at best, and it is rumored that he was plotting with the royalists until word of Velaine reached Paris.

But all this was no insurmountable obstacle. None of the Liberals had ever denounced Napoleon so feverishly as Benjamin Constant, who had called the French emperor “this madman dyed with our blood” and fled to Nantes to avoid having to serve him. But once Constant had been captured and returned to Paris, Napoleon had won him over almost instantly and set him to work on the new constitution. If he could win over Constant, he could surely win over the Deputies and Peers.

The magic of his persuasion was even beginning to work on the war-weary people of France itself. In this he was aided unwittingly by the Prussians— or rather, their newspapers. The Allgemeine Zeitung proclaimed, “We were wrong to show the French any consideration whatsoever. We should have wiped them all out… the whole French nation must be outlawed.” Not to be outdone, the Mercure du Rhin opined that “We must exterminate them; kill them like mad dogs.” Napoleon had only to order these editorials reprinted in the Moniteur to convince much of the public that such sentiments represented the general mood of the Seventh Coalition, and that the French Emperor was the nation’s last hope. (One American historian, Charles Cerniglia, has proposed that Napoleon may have learned this from studying British actions at New Orleans in the wake of General Keane’s capture of that city. In the absence of evidence, this remains mere conjecture.)[1]

In any event, there was no help for it. If the emperor won, he would return and rule, and they would be lucky if he allowed the new parliament to remain in session at all. (And after the glorious triumphs of Velaine and Mayence, who would say he did not have the right?) Whereas if he failed, then, as Fouché put it after the setback at the Zorn, “the crowned heads of Europe would spill every last drop of Christian blood to return Louis the Pig’s bloated arse to his throne and Marie Antoinette’s empty head to her neck.” Thus, the Liberals of Parliament judged their fate to be closely tied to that of Napoleon, whether they wished it so or not.

In the meantime, there was a nation to be governed, which Napoleon could not do from the battlefield. Taxes had to be gathered, conscripts brought to the training fields, supplies procured. Davout’s efforts at fortifying Paris and building camps south and west of the city needed to be supported.

And so a strange political partnership developed. Lanjuinais and his vice-president, Jacques-Charles Dupont de l’Eure, were the public face of the new regime, reading Napoleon’s dispatches aloud in the Champs-Élysées. Meanwhile, Carnot was turning his engineer’s brain to the task of building the Liberal Party into a system for finding reliable men, securing their loyalty and installing them in office. The Moniteur became the Liberal Party's official house organ.

The Party undertook other tasks as well. Wherever opposition (royalist or simply antiwar) threatened to interfere with the purposes of the government, the Liberals unleashed the fédérés, groups of radical workingmen whom Napoleon had despised but whom Carnot was only too pleased to arm and train for the suppression of dissent. (Most of the fédérés were Jacobite rather than Liberal, but few proved unwilling to compromise their principles in exchange for the chance to serve their nation and their emperor.)

If the fédérés were the Party’s naked fist, Fouché and his secret police were its hidden dagger. A born conspirator, Fouché proved a genius at finding royalist plots and bringing them to light — or, when he judged it more suitable, disposing of them in the darkness.

At this point, the Liberal Party’s writ hardly ran in the south or the smaller towns, where royalist sentiment was still a force to be reckoned with. Nonetheless, by the end of July, the two chambers of Parliament and the Liberal Party had become as effective a machine of governance as any in Europe…

Jean-Michel Noailles, The Liberal Party and the Making of Modern France (Eng. trans)

***

[1] Actually, Napoleon did this IOTL.

But Everyone Knows it as Nancy (3)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

Day by day, house by house and block by block, the French were driven back. Their worst day was on August 13, in the so-called “Garden of Horrors,” in which, due to a run of bad luck and some aggressive moves by Barclay de Tolly, over twelve thousand Frenchmen and some nine thousand Russians were killed or wounded. After this day, there was no longer any doubt which side would take possession of the city.

And, indeed, the next day the French were in full retreat from the streets of the city. Barclay de Tolly ordered the pursuit… right into the teeth of hell. Napoleon had spent the previous night arranging his artillery and sharpshooters along the ridge of hills west of the city. The Russians were at the foot of these hills by the time the last French stragglers had passed the line of the emperor’s guns, but they were not close enough to grapple with the enemy and were driven back with heavy losses.

Two days later, Wrede and 100,000 men tried to circle around to the south and launch a flank attack against Napoleon’s line. This flank attack was itself outflanked by Masséna, who had arrived on the battlefield the previous day. With his raw troops reinforced by Rapp’s smaller but more seasoned army, Masséna nearly rolled up the whole Austrian army before they anchored one flank against the Meurthe. After that, both sides returned to skirmishing, avoiding major engagements that might stretch already fragile morale to the breaking point.

Then, on August 22, a new army arrived that would change everything. This was an army of 60,000 Britons — and one Briton in particular…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

August 22, 1815

1:50 p.m.

Jardin Dominique Alexandre Godron, Nancy

Once, this had been one of the most famous botanical gardens in Europe. Now, the various herbs and flowers were largely trampled to death, scorched or grazed upon by cavalry horses. The place smelled of nothing but gunpowder, woodsmoke and blood.

Colonel Neil Campbell (Sir Neil Campbell, knighted to two different orders by the tsar, who now probably wished he hadn’t) stroked his beard and sighed as he reviewed the latest list of casualties. He was becoming quite fond of his little force of soldiers from the free cities of northern Germany. He doubted one man in ten of them actually cared who ruled Europe, but they had acquitted themselves well in battle and did not blame or resent him, which was a refreshing change from everyone else in this army.

Campbell was beginning to wish someone would have the discourtesy to tell him to his face that this was all his doing. Then at least he could defend himself. He could say, “What should I have done — leapt upon him and wrestled him to the ground? The guards at Elba were under his command, not mine!” Or he could say, “It was not I who chose to put the most dangerous man alive in a ‘prison’ with no bars, no locks and no guards but one Scotsman with no official sanction and a bad war wound!”

All of which was true. Lord Liverpool had said as much himself before Parliament back in April. So had Lord Castlereagh, along with a great deal else concerning the unwisdom of the Treaty of Fontainebleau and its signatories. (Castlereagh had been very clear to Campbell about the extent of his mandate: “I am to desire that you will continue to consider yourself a British resident in Elba, without assuming any further official character than that in which you are already received.”)

But if he said these things with no prompting from anyone, it would seem like an outward response to the inner scourge of a guilty conscience… which is exactly what they were. To the extent that he had had any power at all to carry out his duty, he had failed. The captain of the sloop HMS Partridge had failed equally badly in the matter, but at least he’d been there to do it. Whereas Campbell had been on the mainland, fornicating with his mistress, while Bonaparte made his escape.

“There you are,” came a voice that spoke crisp English without a foreign accent. “I’ve been looking for you.”

Campbell looked up. He scrambled to his feet and saluted, wincing at the sudden pain in his back (curse that blundering Cossack who’d nearly killed him by mistake!)

“Sir! Your Grace!” he blurted out. “Thank God you’re here!”

And, indeed, the next day the French were in full retreat from the streets of the city. Barclay de Tolly ordered the pursuit… right into the teeth of hell. Napoleon had spent the previous night arranging his artillery and sharpshooters along the ridge of hills west of the city. The Russians were at the foot of these hills by the time the last French stragglers had passed the line of the emperor’s guns, but they were not close enough to grapple with the enemy and were driven back with heavy losses.

Two days later, Wrede and 100,000 men tried to circle around to the south and launch a flank attack against Napoleon’s line. This flank attack was itself outflanked by Masséna, who had arrived on the battlefield the previous day. With his raw troops reinforced by Rapp’s smaller but more seasoned army, Masséna nearly rolled up the whole Austrian army before they anchored one flank against the Meurthe. After that, both sides returned to skirmishing, avoiding major engagements that might stretch already fragile morale to the breaking point.

Then, on August 22, a new army arrived that would change everything. This was an army of 60,000 Britons — and one Briton in particular…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

August 22, 1815

1:50 p.m.

Jardin Dominique Alexandre Godron, Nancy

Once, this had been one of the most famous botanical gardens in Europe. Now, the various herbs and flowers were largely trampled to death, scorched or grazed upon by cavalry horses. The place smelled of nothing but gunpowder, woodsmoke and blood.

Colonel Neil Campbell (Sir Neil Campbell, knighted to two different orders by the tsar, who now probably wished he hadn’t) stroked his beard and sighed as he reviewed the latest list of casualties. He was becoming quite fond of his little force of soldiers from the free cities of northern Germany. He doubted one man in ten of them actually cared who ruled Europe, but they had acquitted themselves well in battle and did not blame or resent him, which was a refreshing change from everyone else in this army.

Campbell was beginning to wish someone would have the discourtesy to tell him to his face that this was all his doing. Then at least he could defend himself. He could say, “What should I have done — leapt upon him and wrestled him to the ground? The guards at Elba were under his command, not mine!” Or he could say, “It was not I who chose to put the most dangerous man alive in a ‘prison’ with no bars, no locks and no guards but one Scotsman with no official sanction and a bad war wound!”

All of which was true. Lord Liverpool had said as much himself before Parliament back in April. So had Lord Castlereagh, along with a great deal else concerning the unwisdom of the Treaty of Fontainebleau and its signatories. (Castlereagh had been very clear to Campbell about the extent of his mandate: “I am to desire that you will continue to consider yourself a British resident in Elba, without assuming any further official character than that in which you are already received.”)

But if he said these things with no prompting from anyone, it would seem like an outward response to the inner scourge of a guilty conscience… which is exactly what they were. To the extent that he had had any power at all to carry out his duty, he had failed. The captain of the sloop HMS Partridge had failed equally badly in the matter, but at least he’d been there to do it. Whereas Campbell had been on the mainland, fornicating with his mistress, while Bonaparte made his escape.

“There you are,” came a voice that spoke crisp English without a foreign accent. “I’ve been looking for you.”

Campbell looked up. He scrambled to his feet and saluted, wincing at the sudden pain in his back (curse that blundering Cossack who’d nearly killed him by mistake!)

“Sir! Your Grace!” he blurted out. “Thank God you’re here!”

Day by day, house by house and block by block, the French were driven back. Their worst day was on August 13, in the so-called “Garden of Horrors,” in which, due to a run of bad luck and some aggressive moves by Barclay de Tolly, over twelve thousand Frenchmen and some nine thousand Russians were killed or wounded. After this day, there was no longer any doubt which side would take possession of the city.

And, indeed, the next day the French were in full retreat from the streets of the city. Barclay de Tolly ordered the pursuit… right into the teeth of hell. Napoleon had spent the previous night arranging his artillery and sharpshooters along the ridge of hills west of the city. The Russians were at the foot of these hills by the time the last French stragglers had passed the line of the emperor’s guns, but they were not close enough to grapple with the enemy and were driven back with heavy losses.

Two days later, Wrede and 100,000 men tried to circle around to the south and launch a flank attack against Napoleon’s line. This flank attack was itself outflanked by Masséna, who had arrived on the battlefield the previous day. With his raw troops reinforced by Rapp’s smaller but more seasoned army, Masséna nearly rolled up the whole Austrian army before they anchored one flank against the Meurthe. After that, both sides returned to skirmishing, avoiding major engagements that might stretch already fragile morale to the breaking point.

Then, on August 22, a new army arrived that would change everything. This was an army of 60,000 Britons — and one Briton in particular…

P.G. Sherman, 1815 And All That

August 22, 1815

1:50 p.m.

Jardin Dominique Alexandre Godron, Nancy

Once, this had been one of the most famous botanical gardens in Europe. Now, the various herbs and flowers were largely trampled to death, scorched or grazed upon by cavalry horses. The place smelled of nothing but gunpowder, woodsmoke and blood.

Colonel Neil Campbell (Sir Neil Campbell, knighted to two different orders by the tsar, who now probably wished he hadn’t) stroked his beard and sighed as he reviewed the latest list of casualties. He was becoming quite fond of his little force of soldiers from the free cities of northern Germany. He doubted one man in ten of them actually cared who ruled Europe, but they had acquitted themselves well in battle and did not blame or resent him, which was a refreshing change from everyone else in this army.

Campbell was beginning to wish someone would have the discourtesy to tell him to his face that this was all his doing. Then at least he could defend himself. He could say, “What should I have done — leapt upon him and wrestled him to the ground? The guards at Elba were under his command, not mine!” Or he could say, “It was not I who chose to put the most dangerous man alive in a ‘prison’ with no bars, no locks and no guards but one Scotsman with no official sanction and a bad war wound!”

All of which was true. Lord Liverpool had said as much himself before Parliament back in April. So had Lord Castlereagh, along with a great deal else concerning the unwisdom of the Treaty of Fontainebleau and its signatories. (Castlereagh had been very clear to Campbell about the extent of his mandate: “I am to desire that you will continue to consider yourself a British resident in Elba, without assuming any further official character than that in which you are already received.”)

But if he said these things with no prompting from anyone, it would seem like an outward response to the inner scourge of a guilty conscience… which is exactly what they were. To the extent that he had had any power at all to carry out his duty, he had failed. The captain of the sloop HMS Partridge had failed equally badly in the matter, but at least he’d been there to do it. Whereas Campbell had been on the mainland, fornicating with his mistress, while Bonaparte made his escape.

“There you are,” came a voice that spoke crisp English without a foreign accent. “I’ve been looking for you.”

Campbell looked up. He scrambled to his feet and saluted, wincing at the sudden pain in his back (curse that blundering Cossack who’d nearly killed him by mistake!)

“Sir! Your Grace!” he blurted out. “Thank God you’re here!”

Hee hee, Nosey's here!

But Everyone Knows it as Nancy (4)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

“Sir Charles Napier sends his warm regards,” said Wellington. “He is with my army. He looks forward to seeing you again.”

“And I look forward to seeing Sir Charles.”

Over tea (which Wellington had brought with him, eliciting a fresh wave of gratitude from the under-supplied Campbell) they discussed the tactical situation.

“Before your arrival, sir, the Coalition army numbered some 450,000,” said Campbell. “We’re not quite sure how many men Napoleon has, but it can’t be more than 200,000. Probably a little less.”

“Good. Who commands?”

“Officially — and only officialy — King Louis.”

Wellington nearly sprayed out a mouthful of tea in astonishment.

“He’s in Kaiserslautern right now, and we are here to restore him to his kingdom, after all,” said Campbell. “In practice, Württemberg, Wrede and Barclay de Tolly are in command of various parts of the battlefield. They meet once a morning to discuss strategy.”

“That’s not so good. How are the armies performing?”

“The Russians, even after their casualties, have the largest army. They’re having their usual trouble with actually bringing all those men to the front where they’re needed rather than leaving them guarding the baggage train or attending on some nobleman, but I would say they’re better at it than they were two years ago. As for the Austrians, at the moment they’re performing better than the Russians, but I’m told morale in their ranks is getting low.”

“I gather there is no hope of help from Prussia?”

“Not this year. Worse, Bernadotte and his men have had to abide in Kaiserslautern to free enough Prussians to combat the Polish rebels. A great pity, sir; they were the finest soldiers I have ever seen… apart from our own, of course.”

Campbell took a map out of his pocket and unfolded it. Wellington scowled as he studied the dispositions.

“One might have thought,” he growled, “that since we outnumber the enemy better than two to one, we would surround them rather than the other way around.”

“It’s not quite as bad as that, sir. We did take d’Amance last week, and we’ve managed to push Masséna and Rapp back across the Moselle… but as you say, sir, it’s not as it should be.

“We have them outgunned as well, but not by so much — perhaps three to two rather than two to one — and theirs are better positioned.”

“That at least makes sense. They don’t have to haul cannon, powder and shot across all Europe, and they must have captured a deal of our ordnance at Velaine and Mainz. And they know the lay of the land better than we. How are we provisioned?”

“Not very well, I’m afraid. Keeping this many people fed and armed would be enough of a problem without Ney and his irregulars.”

“Someone should do something about that damned traitor.”

“It’s been discussed. The Vosges don’t look like much on a map, but they’re a labyrinth. He could be hiding anywhere. Barclay de Tolly says we should call for a couple of voiskos of Cossacks to hunt him down, but King Louis disagrees.”

“I can well imagine.” The Cossacks were among the best light cavalry in the world (even Bonaparte admitted as much, it was said) but you didn’t turn them loose in any country you cared about.

“Even if the king relents, it would take some time to bring them here and still more time to capture Ney.”

“And in the meantime, they’d be more mouths to feed,” said Wellington. “Damnation, Campbell, the more I hear the more I think we could actually lose this battle! It’s clear that Boney has chosen, for reasons of his own, to make this his final stand, but why are we obliging him in this? Why are we not forcing him to withdraw and fight us on open ground? And why has the fighting grown so desultory over the last week? Tell me this.”

Campbell hesitated.

“You must understand, sir,” he said, “that I have no friends in this army — indeed, the longer the war goes on and the more blood the tyrant sheds, the more whisperings and sidelong looks I am treated to by the others. Most of my information comes from Sir Richard Croft, who is back in Kaiserslautern with King Louis.”

Wellington blinked in surprise. “The Royal Family’s own physician is attending the king of France?”

“His health is of paramount importance, and…” Campbell flushed red and looked at his desk. “Given the circumstances of Bonaparte’s escape, the Crown deemed it wise to make a special effort to show our allegiance to the Bourbon cause. In any event, you might do better to consult Sir Richard than myself. He often converses with the king, and the king corresponds with the generals more often than I can speak to them.”

“That’s as may be. But he, as you say, is in Kaiserslautern, and you are here, and I am consulting you. Others may think what they please, Sir Neil. I value your judgment.”

“God bless you, sir.” Campbell took a deep breath. “There are two answers to your questions, sir. The first is that given the precarious state of our supply train, we daren’t let the Corsican get behind us.”

“Insufficient. Boney has a large army and supply train of his own to think about. What is the second answer?”

“The second answer is… politics.”

“Oh dear.”

“Perhaps ‘politics’ is not the right word. ‘Statecraft’ might be better. Sir Richard tells me that the one thing the king of France doesn’t want is huge Coalition armies roaming the length and breadth of his kingdom, living half off the land.”

“Understandable, but are the generals truly willing to accede so completely to His Majesty’s wishes?”

“Württemberg and Wrede are, sir. As far as they are concerned, the Treaty of Alliance against Bonaparte is exactly what it says — a war to be waged against one man who happens to have a very large bodyguard — and therefore the best strategy is to aim all our efforts to his capture or death. De Tolly disagrees. His opinions, so far as I know them, are very much like yours. At the heart of it is that the emperor of Austria desires that at the end of this war, France be strong and unravaged, so as to maintain the balance of power in Europe — something to which the tsar is indifferent if not hostile.”

Wellington nodded. “This is of a piece with what Lord Castlereagh and I saw in Vienna, but I hate to see it here with a war to be fought.”

“Hitherto, Barclay de Tolly has been willing to accede to the wishes of the Austrian princes, as they have achieved more success on the battlefield than he has. But now, I think, he is beginning to believe that they expect him to pay the lion’s share of the butcher’s bill… if you’ll pardon a mixed metaphor.”

“I may as well tell you that I, too, have been instructed to give thought to statesmanship as well as strategy,” said Wellington. “The Crown, like our Austrian allies, desires a swift end to Bonaparte’s depredations and a strong France under King Louis. In short, they desire as much as possible a return to what was the status quo before the Corsican took the throne again.”

Campbell sank in his chair and put his head in his hands. None of this need ever have happened. If only he’d been given more to work with… if only he’d been there… and how many thousands of good men were dead now?

Wellington sighed and leaned in closer.

“Soldier, I will speak in your defense before the King of France, the King of England or the King of Heaven if necessary,” he said quietly. “In return, I expect that you will do your duty, put aside this futile self-recrimination and devote your mind entirely to the question of how to defeat the enemy before us today.”

Campbell had to turn away. Entirely against his will, his eyes had filled with tears.

“I… shall… do all in my power to do as you say sir,” he choked out. He took several deep breaths and blinked away the tears.

“Whatever we’re going to do, sir, we’d better do it quickly,” Campbell said. “Bonaparte is reinforcing Masséna and Rapp in the south, and I am told he is trying to put guns on riverboats somewhere south of here. He may be trying to replicate his success against Blücher on a larger scale.”

“Not while I draw breath, he won’t.”

“There is one more thing, sir,” said Campbell. “Talleyrand is in Kaiserslautern with the king, and in regular correspondence with our commanders in the field.”

After a long pause, Wellington said, “I see. What might he be up to?”

“The devil’s work, I’m sure, sir. More than that… Sir Richard doesn’t know, and so I cannot know.”

“So be it. All the more reason to take down Bonaparte quickly. Will the commanders listen to me?”

“To you? Yes, sir. I believe they still hold you in high regard.”

“Good. Tomorrow morning, then, I shall put forward my plan at their meeting.”

“You have a plan already, sir?”

“No,” said Wellington looking at the map, “but I shall.”

***

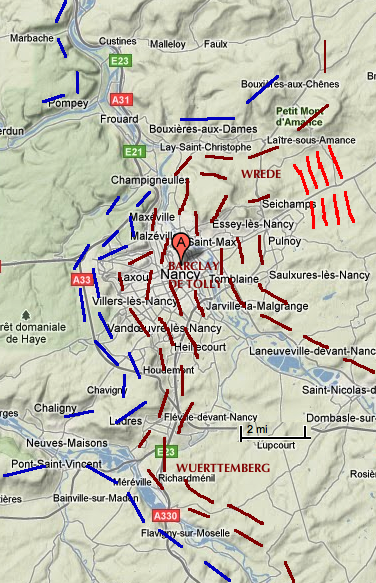

Note: Obviously this isn't the map Wellington is looking at. This is just something I slapped together to give everyone an idea of the disposition of troops. French are blue, British are bright red and the other Coalition troops are dark red.

“And I look forward to seeing Sir Charles.”

Over tea (which Wellington had brought with him, eliciting a fresh wave of gratitude from the under-supplied Campbell) they discussed the tactical situation.

“Before your arrival, sir, the Coalition army numbered some 450,000,” said Campbell. “We’re not quite sure how many men Napoleon has, but it can’t be more than 200,000. Probably a little less.”

“Good. Who commands?”

“Officially — and only officialy — King Louis.”

Wellington nearly sprayed out a mouthful of tea in astonishment.

“He’s in Kaiserslautern right now, and we are here to restore him to his kingdom, after all,” said Campbell. “In practice, Württemberg, Wrede and Barclay de Tolly are in command of various parts of the battlefield. They meet once a morning to discuss strategy.”

“That’s not so good. How are the armies performing?”

“The Russians, even after their casualties, have the largest army. They’re having their usual trouble with actually bringing all those men to the front where they’re needed rather than leaving them guarding the baggage train or attending on some nobleman, but I would say they’re better at it than they were two years ago. As for the Austrians, at the moment they’re performing better than the Russians, but I’m told morale in their ranks is getting low.”

“I gather there is no hope of help from Prussia?”

“Not this year. Worse, Bernadotte and his men have had to abide in Kaiserslautern to free enough Prussians to combat the Polish rebels. A great pity, sir; they were the finest soldiers I have ever seen… apart from our own, of course.”

Campbell took a map out of his pocket and unfolded it. Wellington scowled as he studied the dispositions.

“One might have thought,” he growled, “that since we outnumber the enemy better than two to one, we would surround them rather than the other way around.”

“It’s not quite as bad as that, sir. We did take d’Amance last week, and we’ve managed to push Masséna and Rapp back across the Moselle… but as you say, sir, it’s not as it should be.

“We have them outgunned as well, but not by so much — perhaps three to two rather than two to one — and theirs are better positioned.”

“That at least makes sense. They don’t have to haul cannon, powder and shot across all Europe, and they must have captured a deal of our ordnance at Velaine and Mainz. And they know the lay of the land better than we. How are we provisioned?”

“Not very well, I’m afraid. Keeping this many people fed and armed would be enough of a problem without Ney and his irregulars.”

“Someone should do something about that damned traitor.”

“It’s been discussed. The Vosges don’t look like much on a map, but they’re a labyrinth. He could be hiding anywhere. Barclay de Tolly says we should call for a couple of voiskos of Cossacks to hunt him down, but King Louis disagrees.”

“I can well imagine.” The Cossacks were among the best light cavalry in the world (even Bonaparte admitted as much, it was said) but you didn’t turn them loose in any country you cared about.

“Even if the king relents, it would take some time to bring them here and still more time to capture Ney.”

“And in the meantime, they’d be more mouths to feed,” said Wellington. “Damnation, Campbell, the more I hear the more I think we could actually lose this battle! It’s clear that Boney has chosen, for reasons of his own, to make this his final stand, but why are we obliging him in this? Why are we not forcing him to withdraw and fight us on open ground? And why has the fighting grown so desultory over the last week? Tell me this.”

Campbell hesitated.

“You must understand, sir,” he said, “that I have no friends in this army — indeed, the longer the war goes on and the more blood the tyrant sheds, the more whisperings and sidelong looks I am treated to by the others. Most of my information comes from Sir Richard Croft, who is back in Kaiserslautern with King Louis.”

Wellington blinked in surprise. “The Royal Family’s own physician is attending the king of France?”

“His health is of paramount importance, and…” Campbell flushed red and looked at his desk. “Given the circumstances of Bonaparte’s escape, the Crown deemed it wise to make a special effort to show our allegiance to the Bourbon cause. In any event, you might do better to consult Sir Richard than myself. He often converses with the king, and the king corresponds with the generals more often than I can speak to them.”

“That’s as may be. But he, as you say, is in Kaiserslautern, and you are here, and I am consulting you. Others may think what they please, Sir Neil. I value your judgment.”

“God bless you, sir.” Campbell took a deep breath. “There are two answers to your questions, sir. The first is that given the precarious state of our supply train, we daren’t let the Corsican get behind us.”

“Insufficient. Boney has a large army and supply train of his own to think about. What is the second answer?”

“The second answer is… politics.”

“Oh dear.”

“Perhaps ‘politics’ is not the right word. ‘Statecraft’ might be better. Sir Richard tells me that the one thing the king of France doesn’t want is huge Coalition armies roaming the length and breadth of his kingdom, living half off the land.”

“Understandable, but are the generals truly willing to accede so completely to His Majesty’s wishes?”

“Württemberg and Wrede are, sir. As far as they are concerned, the Treaty of Alliance against Bonaparte is exactly what it says — a war to be waged against one man who happens to have a very large bodyguard — and therefore the best strategy is to aim all our efforts to his capture or death. De Tolly disagrees. His opinions, so far as I know them, are very much like yours. At the heart of it is that the emperor of Austria desires that at the end of this war, France be strong and unravaged, so as to maintain the balance of power in Europe — something to which the tsar is indifferent if not hostile.”

Wellington nodded. “This is of a piece with what Lord Castlereagh and I saw in Vienna, but I hate to see it here with a war to be fought.”

“Hitherto, Barclay de Tolly has been willing to accede to the wishes of the Austrian princes, as they have achieved more success on the battlefield than he has. But now, I think, he is beginning to believe that they expect him to pay the lion’s share of the butcher’s bill… if you’ll pardon a mixed metaphor.”

“I may as well tell you that I, too, have been instructed to give thought to statesmanship as well as strategy,” said Wellington. “The Crown, like our Austrian allies, desires a swift end to Bonaparte’s depredations and a strong France under King Louis. In short, they desire as much as possible a return to what was the status quo before the Corsican took the throne again.”

Campbell sank in his chair and put his head in his hands. None of this need ever have happened. If only he’d been given more to work with… if only he’d been there… and how many thousands of good men were dead now?

Wellington sighed and leaned in closer.

“Soldier, I will speak in your defense before the King of France, the King of England or the King of Heaven if necessary,” he said quietly. “In return, I expect that you will do your duty, put aside this futile self-recrimination and devote your mind entirely to the question of how to defeat the enemy before us today.”

Campbell had to turn away. Entirely against his will, his eyes had filled with tears.

“I… shall… do all in my power to do as you say sir,” he choked out. He took several deep breaths and blinked away the tears.

“Whatever we’re going to do, sir, we’d better do it quickly,” Campbell said. “Bonaparte is reinforcing Masséna and Rapp in the south, and I am told he is trying to put guns on riverboats somewhere south of here. He may be trying to replicate his success against Blücher on a larger scale.”

“Not while I draw breath, he won’t.”

“There is one more thing, sir,” said Campbell. “Talleyrand is in Kaiserslautern with the king, and in regular correspondence with our commanders in the field.”

After a long pause, Wellington said, “I see. What might he be up to?”

“The devil’s work, I’m sure, sir. More than that… Sir Richard doesn’t know, and so I cannot know.”

“So be it. All the more reason to take down Bonaparte quickly. Will the commanders listen to me?”

“To you? Yes, sir. I believe they still hold you in high regard.”

“Good. Tomorrow morning, then, I shall put forward my plan at their meeting.”

“You have a plan already, sir?”

“No,” said Wellington looking at the map, “but I shall.”

***

Note: Obviously this isn't the map Wellington is looking at. This is just something I slapped together to give everyone an idea of the disposition of troops. French are blue, British are bright red and the other Coalition troops are dark red.

Last edited:

Just wanted to say that I've been watching this timeline with interest. This usually doesn't happen for me when timelines are focused on military developments, but your writing keeps things interesting for me.

On a less serious note, I also wanted to say this:

Does anyone else hear horses neighing whenever they see this name in print?

On a less serious note, I also wanted to say this:

...Blücher...

Does anyone else hear horses neighing whenever they see this name in print?

Lycaon pictus

Donor

Just wanted to say that I've been watching this timeline with interest. This usually doesn't happen for me when timelines are focused on military developments, but your writing keeps things interesting for me.

Thank you. You'll be glad to know that when this cruel war is over, I'll be able to give a little more attention to political changes in the U.S., Britain, France and elsewhere.

(I'm not sure about the horses, but at least one other poster has spelled his name "Blutcher." I haven't asked if that was on purpose.

Share: