CHAPTER 13 – UNSCRIPTED EVENT

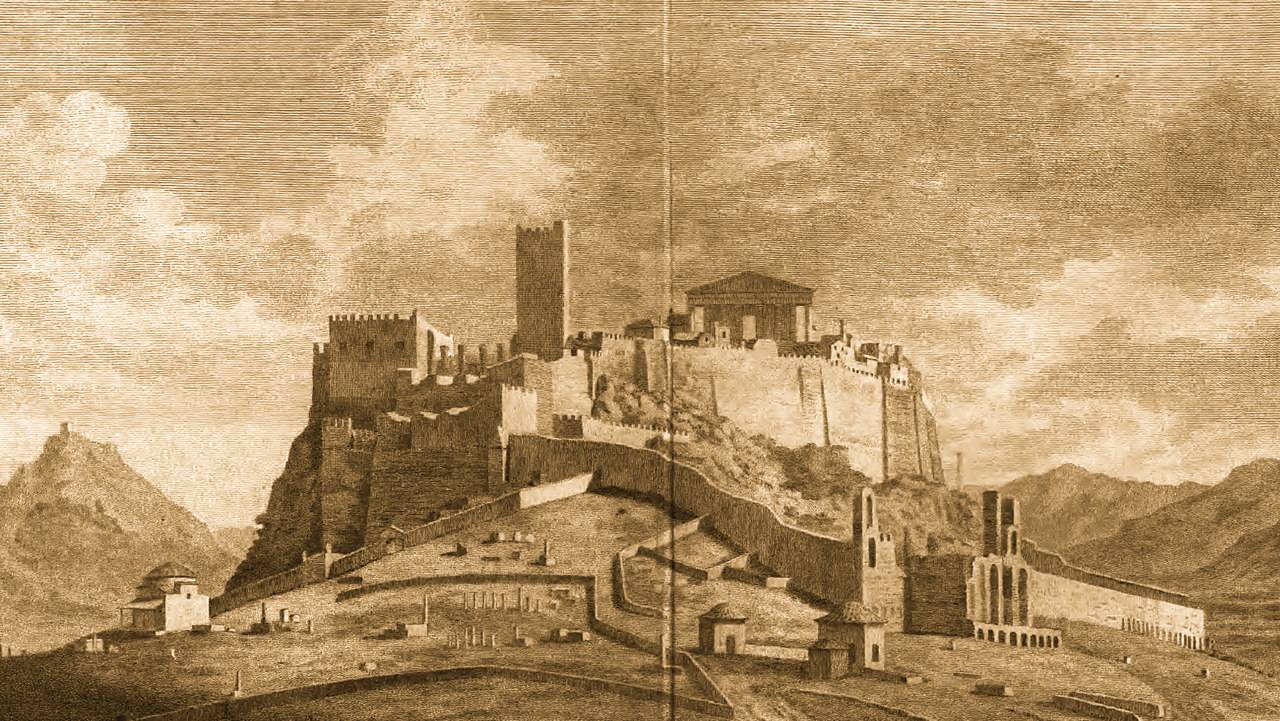

- The Acropolis of Athens in the mid-18th century. The discernible fortifications, eventually demolished in the mid-19th century, date back to the Duchy of Athens era, established by the de la Roche and later expanded in Acciaioli periods, a mighty fortification during the 14th and 15th Century.

The Duchy of Athens was a Latin or Frankish state in Greece that existed from 13th Century to Early 15th Century. It was created in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204 CE) and would be ruled for the majority of its history by the Burgundian de la Roche family, the Catalans under the rule of the kings of Sicily, and the Florentine Acciaioli family. As a Latin state in Greece, it was closely connected to its neighboring states as well as the rulers of southern Italy and imposed feudal law on its small territory in Attica and Boeotia.

******************************************

The New Year's festivities had barely waned in Constantinople, and the city's streets still echoed with the joyous laughter and chatter of its citizens. Amidst this jubilation, a momentous event awaited the Roman Empire - the arrival of a large envoy from Italy, bearing tidings of yet another celebration. For in a display of Christian unity and Roman diplomatic prowess, the newly elected Pope Martin V had offered a marital alliance between three prominent Catholic Italian noblewomen and Roman princes Andronikos, Theodoros, and Ioannes. If accepted by Constantinople, the wedding shall be determined at a later stage.

As emperor Manuel accepted the offer, the news of a new marital alliance with Italy spread like wildfire among the ordinary Romans, igniting a flurry of excitement and gossip. The identity of the brides, their appearance, attire, and dowry became the talk of the town, with speculation and curiosity filling the air. For the influential men of the Empire, however, these marriage offers represented a beacon of hope and support from the West. Rumors began to swirl within the upper circles of society, whispering tales of a potential crusade led by the Catholic world, aimed at evicting the Ottoman menace from the Empire's borders.

Last time the Crusade of Nicopolis almost destroyed the Ottomans, were it not for a foolish charge by overconfident French knights. God bless the victorious Sultan Bayezid the Thunderbolt was then defeated by Timur. This time, with the Ottomans still recovering its strength, another Crusade would surely finish the undone business.

As Constantinople immersed in celebration, the news of the marriages had also reached Andronikos, who had returned to his domain in Thessaloniki. Unlike his eager subordinates, Andronikos received the news with a reserved demeanor, for his thoughts were firmly fixated on the potential crusade, as the meeting in Konstanz had instilled a determined ambition in him to participate in this war that could in once strike lift the empire from its decline.

What Andronikos was anticipating was a secret letter delivered to him by a messenger who blended into the grand envoy from Rome. This man brought with him the latest development of the preparation for a Crusade, among other intelligence, written by none other than Nicholas Eudaimonoioannes, the Roman ambassador to the Latin world.

In the letter, Nicholas described to Andronikos in a regrettable tone the aftermath of the Council of Konstanz, which saw the new Pope, Martin V, elected. As the Latin Church had been fragmentated for decades, the restoration effort was massive, the bishops and cardinals had to negotiate painstakingly the redistribution of Church authorization, find compromise in personnel appointment and dismissal, reallocation of Church treasures, so on and so forth. The Council was thus expected to last another season, and before that nothing could be done.

Not only are the attention of the Catholic Church devolved fully into internal affairs, the other main proponent of the Crusade against the Ottomans, the Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund also had his attention demanded by a rising heretic unrest in Bohemia: thousands of followers of the heretic preacher Jan Huss, who were executed in 1415 at the Council of Konstanz, had made unacceptable demands of religious tolerance, and Sigismund was in no mood to accept. With the Catholic Church and emperor Sigismund both occupied, a timetable for the Crusade was yet to be settled.

Andronikos was undoubtedly disappointed by the news of slow progress, which stood in stark contrast to what Sigismund had promised to him months ago, and he began to understand his father, emperor Manuel’s position better. The Empire of the Romans must save itself with or without the help of a Crusade from the West.

As Andronikos’ mind came to reason, he began to assess the situation with a cooler head. The reality of a now uncertain Crusade and the still powerful Ottomans loomed large in his mind, the vast disparity in power between The Roman Empire and the Ottomans are almost insurmountable. The Ottomans excelled in every measurable aspect - from the quality of their army to the vastness of their manpower, tax base, and financial resources. Relying solely on the support of crusading allies would be imprudent, and if the Romans were to engage in this crusade, they must be fully prepared to withstand Ottoman aggression for a prolonged period.

The Romans' territorial holdings after 1405 were predominantly coastal, lacking strategic depth. The Roman army, despite showing potentials in its victory in Achaea, was still too small to face the overwhelming Ottoman force. The spread-out nature of Roman holdings also meant lacked cohesion, making concentration of force difficult. To gain strategic initiative, a forward base of operation and concentration had to be established, and that place must be Thessaloniki.

Fully surrounded in its land borders by vast Ottoman holdings, Constantinople is isolated and trapped. However, its symbolic and political importance, and coupled with its mighty walls and excellent geographic advantage makes it an optimal anvil, to be synchronized with a hammer, coming from south, from the ancient lands of Hellenes where civilization once prospered.

With the successful Achaea campaign last year, almost all of Peloponnese came under Roman hand save a few coastal cities such as Nauflion, Modon, Argos controlled by Venice. Across the narrow Corinthian strait was the Roman outpost of Neopatras which connected Roman forces in Achaea and Morea with Lamia, the Romans control the coastal half of Thessaly, and Thessaloniki in one continuous thin strip of land, the only obstacle to consolidate this collection of holding into a sustainable and defendable domain, was the existence of Duchy of Athens.

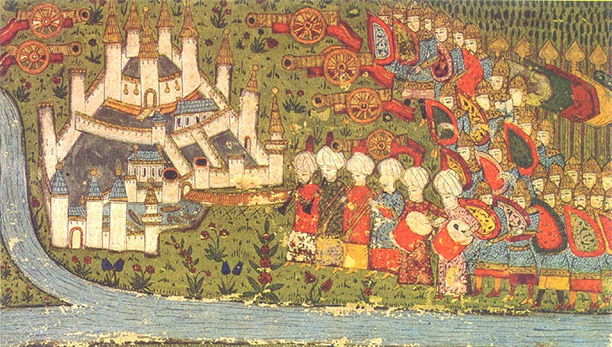

Since his conflict with the Venetians in 1406, Antonio I Acciaioli, the Duke of Athens, had effectively served as a vassal to the Ottomans, intermittently harassing Venetian and Roman territories with swift raids. A strategic wedge between Roman holdings of Thessaloniki and Morea, and threatening Venetian holdings in the important trade hub of Euboea, the Ottomans had always had an extra care for Athens compared to other vassals, often supporting them with generous arms and supplies, sometimes even directing Ottoman troops to assist directly in Athenian raid of Venice.

Just two years ago during the Ottoman-Venetian war of 1416, a combined Ottoman and Athenian force had attacked the Venetians in Euboea, though unsuccessful due to their inferior navy.

With strong Ottoman support, it had always seemed unlikely the weak and terminally ill empire of the Romans could have threatened Antonio. However, the Roman victory in Achaea, combined with successive Ottoman defeats at the hand of rebel Bedreddin had changed the calculation. With the Roman morale were high and their ranks strengthened, all the while Ottomans were copiously distracted in their struggle to contain a massive religious rebellion, it seemed an ideal opportunity for Romans to strike Athens had opened.

Andronikos had no intention to let this rare opportunity go to waste. In early February, he wrote a letter to co-emperor Ioannes in Constantinople, laying out his ideas, and entered into an intensive discussion with Ioannes on the prospects and details of a potential campaign against the Duchy of Athens. Unlike Achaea which were weak and lacked real protection, Duchy of Athens was well consolidated under Antonio and could indeed mobilize a strong resistance, not to mention the possibility of a forceful Ottoman intervention.

Nevertheless, it was agreed between co-emperor and Despot to not finalize any specifics of the campaign as of yet, but begin the preparation for a campaign in earnest, so as to seize the opportunity when it arises.

For Andronikos, the first order of business in his preparation was improvement of armament, particularly firearms. Drawing from his own experiences in the traumatic wars of Achaea, Andronikos saw great promise in these deadly weapons, especially the devastating power of cannons in siege warfare, both in defense and offense, as demonstrated in the siege of Glarentza.

A prospective campaign into Athens must be swift, to minimize the incentive and thus possibility for Ottomans to intervene. Therefore, it was not only important to win field battles, but arguably more important to prevent any prolonged sieges. A situation such as Glarentza would be disastrous to the Romans.

With his war spoil from the loot and confiscation of Latin properties in Achaea, Andronikos had amassed a significant fortune. After paying his army a hefty bonus, he still retained a considerable amount of wealth, including 10.000 ducats in coins and numerous estates and properties worth several thousand more ducats. Throughout the spring of 1418, Andronikos invested heavily in establishing a gun factory modeled after the Venetian Arsenal he saw in Venice, even spending a large sum to hire a former gunsmith foreman of Arsenal.

Andronikos oversaw the construction of the gunsmith with meticulous care, ensuring that it was equipped with the latest technology and skilled craftsmen. He imported rare materials and components from Venice and other parts of Europe, determined to create a formidable arsenal that would give the Romans an edge in the upcoming conflict. Craftsmen from across Italy were invited to Thessaloniki, and the first prototype cannon replicated from one of the Venetian cannons seized by Andronikos from Glarentza and brought back to Thessaloniki was produced in early April, marking the first instance of Roman cannon production.

the news of Bedreddin's triumph over Mehmed and the subsequent defeat of his disciples in Anatolia reached Andronikos by early April. Already acquainted with Bedreddin's beliefs through his interactions with numerous former followers who had become integral members of the epilektoi, Andronikos developed a profound interest in the Mystic Rebel's philosophy, much of which resonated deeply with his own convictions. Particularly intriguing was Bedreddin's unwavering belief in the inherent equality of all men and the necessity for them to share their possessions with each other.

Andronikos' curiosity did not solely extend to theology; he was equally, if not more, fascinated by the potential manpower that fleeing Bedreddin followers could bring to his cause. The epilektoi's social and military experiment had demonstrated remarkable promise, cultivating a loyal, disciplined, and highly capable army at a fraction of the cost of recruiting a similarly powerful mercenary group. If this model could be replicated, it held the potential to become the blueprint for rebuilding the Roman army. What was required, however, was not monetary resources but rather access to unoccupied lands for distribution and a consistent influx of men willing to fight for those lands.

Thessaloniki still possessed vast tracts of unoccupied land, sufficient to accommodate another thousand families, which in turn would translate into a thousand fresh troops. Yet, Andronikos lacked access to able-bodied men. The majority of the Greek populace within the Empire had become accustomed to avoiding active participation in warfare; they excelled as sailors, merchants, or clergymen but were scarce as soldiers.

Realizing that to expand the epilektoi and augment his army's size, Andronikos recognized his reliance on a continuous flow of capable men willing to risk their lives for land. The only viable source of such manpower lay with Bedreddin's followers fleeing Ottoman persecution. Consequently, he dispatched Leontares on a mission with a small navy, tasked with sailing to the western Aegean coast near Izmir, gathering as many refugees as possible, and transporting them back to Thessaloniki to bolster the ranks of the epilektoi.

This continuing influx of ‘heretic’ men into Thessaloniki, occupying land and taking up arms, and the favoritism Andronikos showed them had made the local Diocese of Thessaloniki very uneasy. They had made countless protest to the Despot, objecting what they saw as the poisoning of the mind and land of Christian, all to no avail.

Andronikos had come to the conclusion that to form a capable army enough to project the political will of the empire and protect its land and vital interest was of utmost importance and highest priority, if it meant antagonizing the church, then it is a cost he was willing to pay.

By late April of 1418, Andronikos had implemented most of his intended preparations, and as he busy himself with further implementation, a huge unexpected change of circumstances would disrupt everything he planned and threw his preparations up in the air.

To Andronikos and many Romans disbelief, Antonio I Acciaioli, Duke of Athens, without any warning, launched a surprise attack into the Roman lands of Achaea and Morea, taking the strategically important city of Corinth by a surprise assault which caught the local garrison with their pants down.

Now instead of preparing to defeat the Athenians in offense, Andronikos must now consider how to defeat them in defense.

A few days later, a formal request for assistance arrived in Thessaloniki from Despot Theodoros himself. In his letter, Theodoros urgently appealed to his brother, Andronikos, for military support as the scale of the Athenian incursion had far exceeded his expectations. The fall of Corinth had left Peloponnese vulnerable to Latin advances and plunder, and reports indicated the presence of Ottoman contingents among the Latin ranks. This was not a mere raid; it was a full-scale invasion.

As Theodoros was still striving to consolidate his control over the newly conquered Achaea, he had relocated a significant portion of his resources and troops to that region. Consequently, the defense of Corinth and Morea in general was woefully undermanned and unable to withstand the unexpected Athenian invasion.

Realizing that only he had the necessary manpower to intervene in a timely manner, Andronikos wasted no time in summoning his generals and captains to devise a battle plan. The call to arms was sounded, and on 29 April 1418, a hastily organized army of 2,000 men, consisting of called upon 1500 epilektoi and 500 standing garrison of Thessaloniki, marched out of the gate of Galerius, led by Andronikos personally, heading southward to reinforce his brethren.