You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blue Skies in Camelot (Continued): An Alternate 80s and Beyond

- Thread starter President_Lincoln

- Start date

Yes.Was there any luck with keeping Don Bluth working for Disney thanks to the change in leadership over to Jim Henson?

I apologize for the unclear wording of that previous chapter. Yes, Nimoy (and Spock) are in the film.@President_Lincoln I know we are way kinda past this point but since Leonard Nimoy's career has really taken off ITTL with him winning I think has it been 2 oscars? Anyway I was reading the Star Trek chapter from 1976 and the popular culture update for this first movie and it didn't mention Nimoy so my question is, Was he in the movie? Or is he just done with Star Trek?

Again sorry for the kinda random question but this kinda came into my mind.

Awesome thank you. Also that just work well for Shatner's who that Nimoy got an Oscar before himI apologize for the unclear wording of that previous chapter. Yes, Nimoy (and Spock) are in the film.

Last edited:

hey @President_Lincoln hope you’re having a good weekend but I was wondering if Ralph Bakshi will be making an appearance and if his career a bit better than it was in otl

Last edited:

Thank you, Mr. President, I humbly tip my hat. So far so good on Henson at Disney. I'm curious where you will take him and Disney.his update, of course, owes a great debt of gratitude to Geekhis Khan’s incomparable Hippie in the House of Mouse timeline.

@Geekhis Khan, just in case you didn't know about this already, I figured you'd enjoy this.

It’s a (deserved) high mark of praise for @Geekhis Khan that pretty much everyone agrees that Henson at Disney is just the perfect direction for the company to go in the 80s. You’ve truly created a legacy, sir

It’s nice to see that the Magic Kingdom will remain magic here. Given that it’s a realistically ideal timeline, it certainly makes sense

Ahhhh Blue Skies has its own Hippie in the House of Mouse!!!! LET'S GOOOOO👍🙌🤩

Holy crap! Will this become the successor to @Geekhis Khan's TL? Great idea dude!

Thanks for the heads-up, all. It's increasingly looking like Italo Balbo taking over as Duce and Jim Henson joining Disney will be my lasting legacies in Alternate History.

i'm excited how jim henson replacing eisner will affect disney going forward

hopefully he will live to spawn kingdom hearts

(if that game is even still released ITTL)

i just really want to see the muppets get the justice they deserve other than being seen as preschool crap like in OTL

(thanks to sesame street in the post elmo era)

just like how video games are gonna be art and animation is cinema ITTL

puppetry is broadway (just like with fursuiting)

all of which should be treated like it

hopefully he will live to spawn kingdom hearts

(if that game is even still released ITTL)

i just really want to see the muppets get the justice they deserve other than being seen as preschool crap like in OTL

(thanks to sesame street in the post elmo era)

just like how video games are gonna be art and animation is cinema ITTL

puppetry is broadway (just like with fursuiting)

all of which should be treated like it

Last edited:

Thank you! Hope you are having a good weekend as well.hey @President_Lincoln hope you’re having a good weekend but I was wondering if Ralph Bakshi will be making an appearance and if his career a bit better than it was in otl

Thank you for the hat-tip, Geekhis.Thank you, Mr. President, I humbly tip my hat. So far so good on Henson at Disney. I'm curious where you will take him and Disney.

Thanks for the heads-up, all. It's increasingly looking like Italo Balbo taking over as Duce and Jim Henson joining Disney will be my lasting legacies in Alternate History.

YES!i'm excited how jim henson replacing eisner will affect disney going forward

hopefully he will live to spawn kingdom hearts

(if that game is even still released ITTL)

i just really want to see the muppets get the justice they deserve other than being seen as preschool crap like in OTL

(thanks to sesame street in the post elmo era)

just like how video games are gonna be art and animation is cinema ITTL

puppetry is broadway (just like with fursuiting)

all of which should be treated like it

The path video games take in this timeline is something I'm really looking forward to, especially because of how they play into politics. Part of the 1983 video game crash was all of the porn games getting released for consoles, and there being little regulation stopping kids from getting their hands on them. And later on, there's the whole "violent video games" debacle. How would a potentially Republican government respond to the 1993-94 congressional hearings on video games, if they still happen in this timeline? What would Bobby think of the porn games issue? Perhaps the ESRB or something like it is formed earlier.just like how video games are gonna be art and animation is cinema ITTL

My biggest prediction, however, is that the first video game-centric update will be named after lyrics from the 1982 song "Pac-Man Fever" by Buckner and Garcia. It just feels appropriate

huh must’ve missed that but the main question I wanted to ask is that will cool world come out as the horror who framed Roger rabbit style movie that it was originally supposed to be, before the “disagreement” he had with the first Director as well as studio interferenceThank you! Hope you are having a good weekend as well.Yes. I believe his Return of the King (never made IOTL) was mentioned or will soon be mentioned as having been made and released here. I'll be sure to follow his career as we move forward as well.

Last edited:

yeah i just hope that the lack of reganomics and the gender specific toy isle ITTL leads to more women/girls playing video games with their S/O instead of nintendo being marketed at soley boys like IOTLThe path video games take in this timeline is something I'm really looking forward to, especially because of how they play into politics. Part of the 1983 video game crash was all of the porn games getting released for consoles, and there being little regulation stopping kids from getting their hands on them. And later on, there's the whole "violent video games" debacle. How would a potentially Republican government respond to the 1993-94 congressional hearings on video games, if they still happen in this timeline? What would Bobby think of the porn games issue? Perhaps the ESRB or something like it is formed earlier.

My biggest prediction, however, is that the first video game-centric update will be named after lyrics from the 1982 song "Pac-Man Fever" by Buckner and Garcia. It just feels appropriate

(kinda like with how the ds was marketed or how the switch is currently being marketed)

if this would lead to a more arcade accurate nintendo console with faux 16 bit graphics with 8 bit backwards compatibility and fm sound (like how the ps2 started with cds but then had dvds later on) this might be the greatest timeline for gaming of all time (and were not even at the part with the snes cd yet)

other than nintendo

i also hope that LEGO also sticks with their classic themes and their focus and both boys and girls playing their sets as well with the more progressive style of TTL (meaning bionicle may not exist), but at least we will still have rock raiders, fabuland and classic space to take its place

Last edited:

Chapter 153

Chapter 153 - Take it on the Run: 1981 Off-Year Elections in the United States

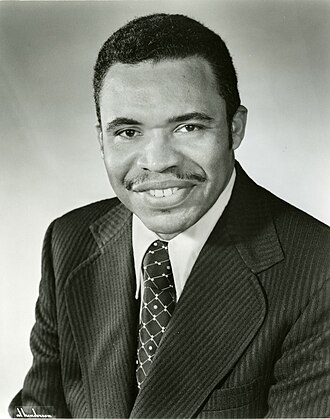

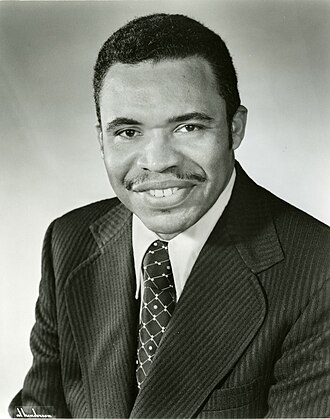

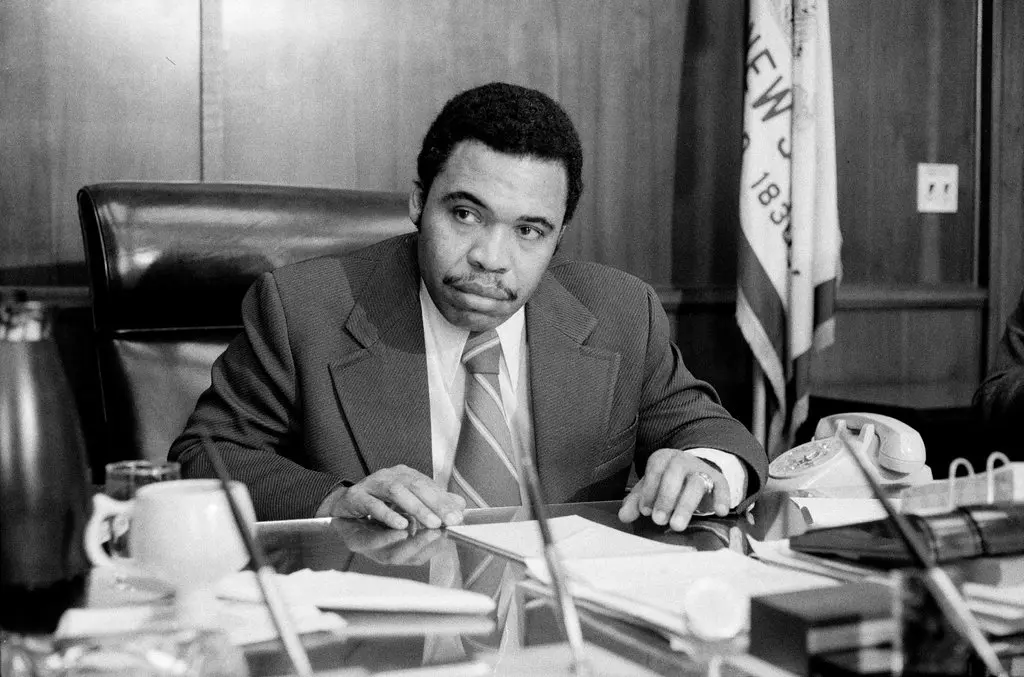

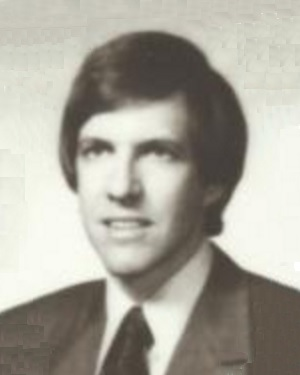

Above: Kenneth Gibson (D - NJ) and Chuck Robb (D - VA), Democratic nominees for governor of New Jersey and Virginia in 1981, respectively.

Above: Kenneth Gibson (D - NJ) and Chuck Robb (D - VA), Democratic nominees for governor of New Jersey and Virginia in 1981, respectively.

“You take it on the run, baby

If that's the way you want it, baby

Then I don't want you around

I don't believe it

Not for a minute

You're under the gun

So you take it on the run” - “Take it on the Run” by REO Speedwagon

“Wherever America is going, New Jersey will get there first.” - Ken Gibson, on the campaign trail

“The fact that our hearts don't speak in the same way is not cause or justification to discriminate.” - Chuck Robb, explaining his support for decriminalizing “sodomy” in the state of Virginia

Though (perhaps understandably) not as widely covered as the midterms, off-year elections are sometimes treated as bell-weathers for the popularity of the president and their party on the national level. For the people of the states of New Jersey and Virginia, of course, there are chances to vote on who will occupy the governor’s mansions of their respective states. For national political wonks, they are also a testing-ground for campaign messaging and strategy. In 1981, both the Garden State and the Old Dominion were due for new chief executives due to both having term-limited incumbents.

Above: Brendan Byrne (D - NJ), outgoing governor in 1981, AKA “the man that couldn’t be bought”.

In New Jersey, that incumbent was Brendan Byrne. A Democrat, originally from West Orange, Byrne first rose to prominence as a prosecutor in the 1960s. While in that position, he was referenced by mobsters operating in the state who’d been wiretapped by the FBI as “the man who couldn’t be bought”, due to his high ethical standards. That comment, combined with an environment in the Tri-State area at the time that considered corruption a critical issue propelled Byrne to statewide fame. In 1973, he was elected Governor, using his “couldn’t be bought” title as a campaign slogan. During his first term, Byrne signed the state’s first income-tax into law, violating a campaign pledge not to do so. Despite a spirited primary challenge and a hard-fought general election in 1977, in which he was widely expected to lose, Byrne defied the odds and won a second term. He spent the next four years overseeing the opening of the state’s first gambling casinos in Atlantic City, increasing openness and transparency in the state government, and preserving a large majority of woodlands and wildlife areas in the state by restricting development. At the tail end of his second term, Byrne’s popularity had rebounded somewhat, but he was leaving office a highly polarizing figure. Conservatives and moderates were still furious that he’d broken his “no income tax” pledge and believed that his restriction on development had cost the state jobs.

The field of Democratic candidates to succeed Byrne was quite crowded. Because the governor declined to name any preferred successor early on, the candidates staked out bold stances on the issues of the day to try and differentiate themselves. Unsurprisingly, they also attempted to tie themselves strongly to President Robert Kennedy, whose approval ratings (in the wake of the attempt on his life by Mark Chapman) hovered around 60% nationally. None of the candidates had a close personal relationship with the president, but that did not stop them from claiming one anyway. Some of the major candidates in the Democratic primary included:

- Herbert J. Buehler, former state senator from Point Pleasant Beach

- John J. Degnan, New Jersey Attorney General

- Frank J. Dodd, state senator from West Orange

- James Florio, U.S. Representative from Runnemede

- Kenneth A. Gibson, Mayor of Newark

- William J. Hamilton, state senator from New Brunswick

- Ann Klein, Human Services Commissioner, former Assemblywoman from Morristown, and candidate for governor in 1973

- Barbara McConnell, state assemblywoman from Flemington

Among the candidates, Jim Florio had run against Byrne in the Democratic primary four years prior, and thus enjoyed the most name recognition throughout the state. Florio staked out his ‘81 campaign on two key issues: a renewed pledge for no new taxes; and being the only Democratic candidate to receive an endorsement from the National Rifle Association. “Pro-gun” and “anti-crime”, Florio vowed to continue to fight corruption in Trenton. His campaign suffered, however, as he remained in Washington, D.C., serving out his term in Congress.

Florio’s absence and Byrne’s initial refusal to back any one candidate (he eventually endorsed Degnan, but by then the impact of the endorsement was probably minimal) stood to benefit the rest of the field, of course. Among the other candidates, one in particular was able to leverage this vacuum in the media and on the stump to his advantage.

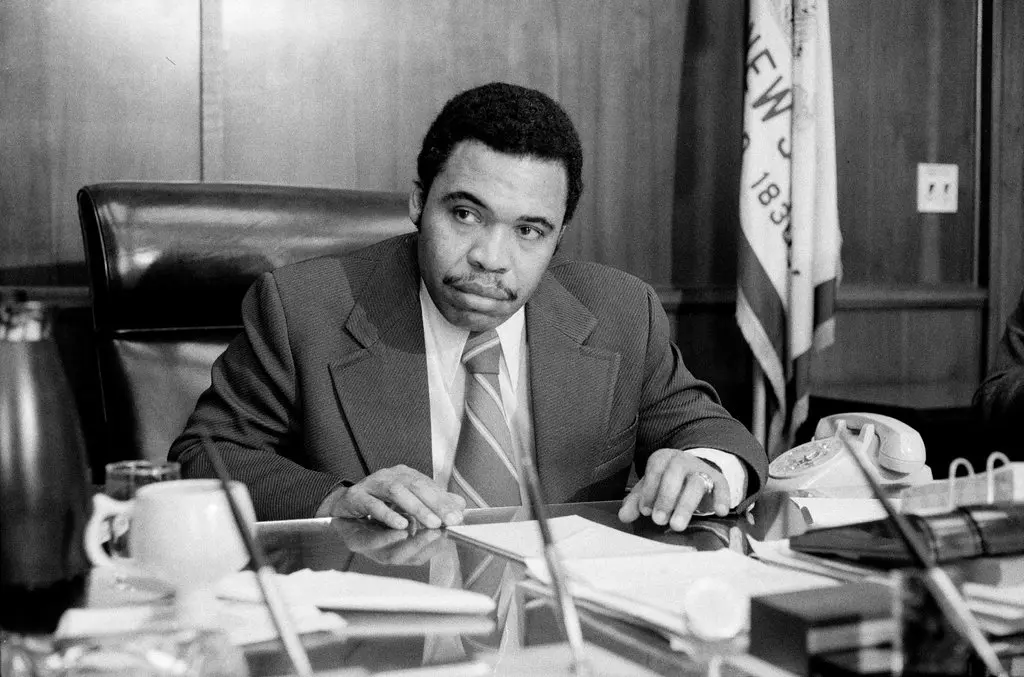

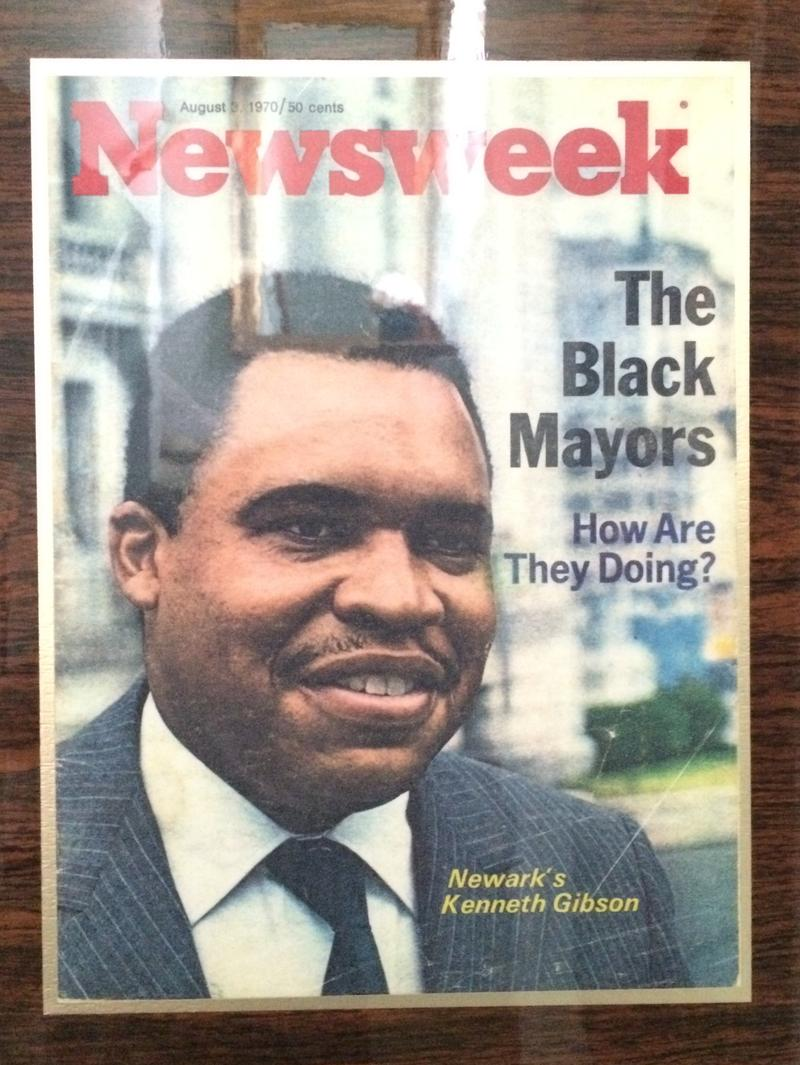

Kenneth Allen Gibson, born May 15th, 1932, was the 36th Mayor of Newark, New Jersey, a position which he had held since first being elected back in 1970. Thanks to that position, Gibson became the first African American to serve as mayor of a major city in the Northeastern United States.

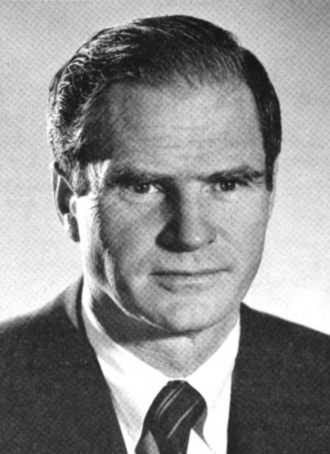

Above: Ken Gibson on the cover of Newsweek.

Gibson was a Newark native. As a teenager, he attended Central High School, where he played with a dance band after school to bring in income needed for his family. After graduation, he studied civil engineering in college, but financial challenges forced him to drop out of school after a few months in school. He then worked in a factory, served in the military and later worked for the New Jersey Highway Department, completing his engineering degree in 1963 by taking night classes.

In 1970, Gibson won election as Mayor as a reformer. At the time, Gibson noted that, “Newark may be the most decayed and financially crippled city in the nation.” He alleged that the previous mayor, Hugh Addonizio, had been “hopelessly corrupt”. Sure enough, shortly after Gibson was elected, Addonizio was convicted of conspiracy and extortion.

Gibson was also seen as a representative of the city’s sizable African-American population, many of whom were migrants or whose parents or grandparents had come North in the Great Migration. The city's industrial power had diminished sharply, however. Deindustrialization since the 1950s cost tens of thousands of jobs when African Americans were still arriving from the South looking for better opportunities than in their former communities. Combined with forces of suburbanization and racial tensions, the city encountered problems similar to those of other major industrial cities of the North and Midwest in the 1960s - increasing poverty and dysfunction for families left without employment. The city was scarred by race riots in 1967, three years before Gibson took office. Many businesses and residents left the city after the riots and were reluctant to return.

After being re-elected in 1974, Gibson went on to become the first African-American president of the United States Conference of Mayors, serving in that role for just over a year from 1976 - 1977.

Though he was viewed by many, both within Newark and beyond as a symbol of hope and the possibility of change, some of his supporters did feel alienated by some of his policy decisions while in office. Namely, in a bid to bring businesses and jobs back to Newark, he approved tax breaks and sweetheart deals to state and corporate interests, and increased funding for the city’s police force, even as its social services saw their budgets’ slashed due to a shrinking tax base.

Nevertheless, he won a third term in 1978 and by 1980, for most, the bloom was very much still on the rose, so to speak. 49 years old in 1981, Gibson announced his candidacy for governor by claiming that he was “the candidate for progress”. He barnstormed the state, delivering impassioned speeches, and calling on his fellow Garden Staters to embrace the “change” that he claimed to represent. For many, the unspoken nature of that “change” was, largely, the color of Gibson’s skin.

Gibson aimed to be the first African-American governor not just in New Jersey’s history, but across the Northeast in general. “If Charles Evers can be elected the United States Senator from Mississippi on the Democratic ticket,” Gibson privately told his staff. “Then I believe that the people of New Jersey may be ready for a man of color as governor.” That said, Gibson was also careful not to paint himself as the “black candidate” for that office. He feared (unfortunately, justifiably) that tying himself too closely to that label could backfire on him. Instead, he spoke in more vague terms of “change” and “progress” and “a new generation of leadership”. In that way, he largely adapted the Kennedy brand of optimism and hope for the future.

Across the state, people’s eyes turned to Gibson. The crowded nature of the primary played to his advantage as well. By cultivating a loyal, dedicated following, Gibson outshone several of the less well-known candidates, and set himself up to challenge the “absentee candidate” - Florio. When the Democratic primary was held, on June 2nd, 1981, the number of candidates was thought to be the deciding factor.

With just 26.2% of the vote, Ken Gibson, Mayor of Newark, managed to eke out a win over Florio, who scored 25.4%, as well as all the other candidates. Though hardly a decisive victory, Gibson would be the Democratic nominee for governor of New Jersey in 1981. In a massive rally in his hometown, Gibson celebrated with his wife, Camille, and a crowd of devoted supporters.

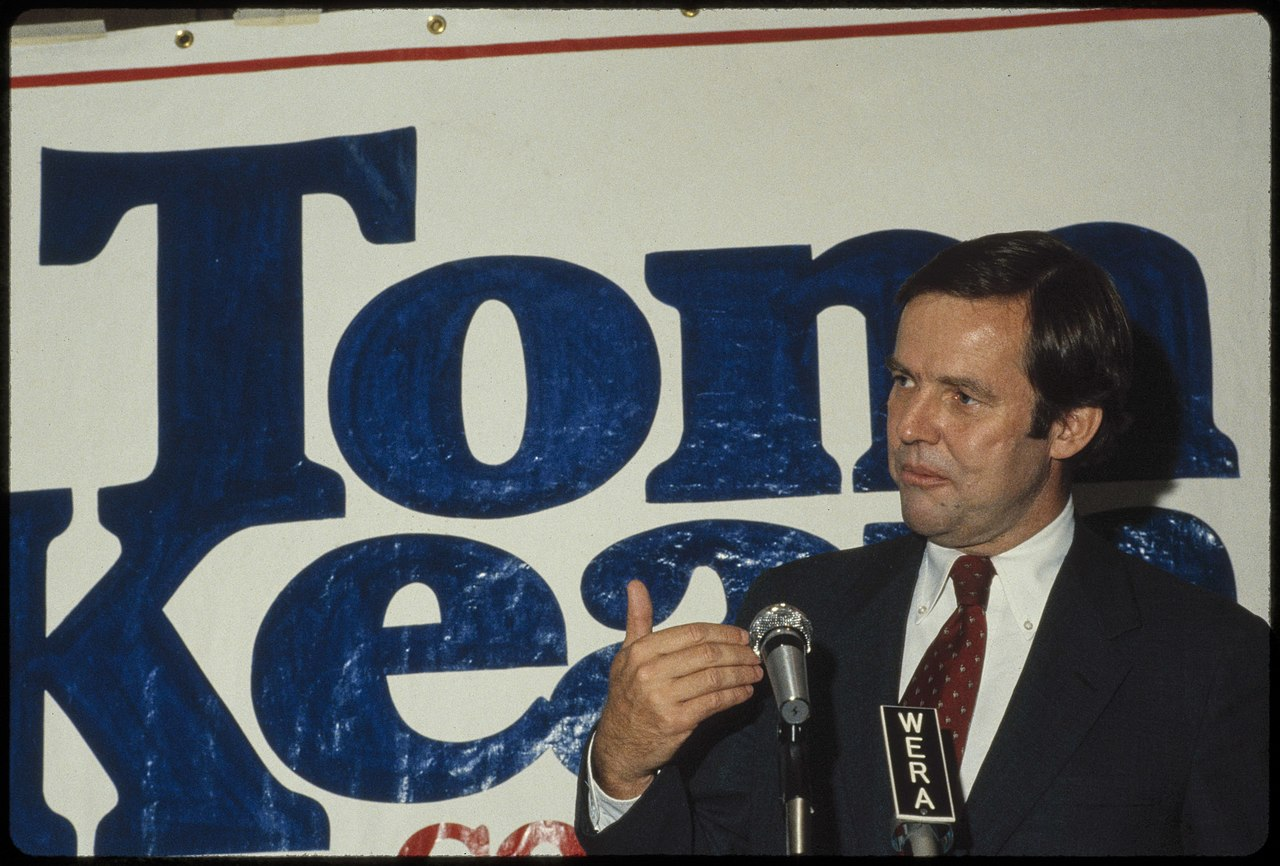

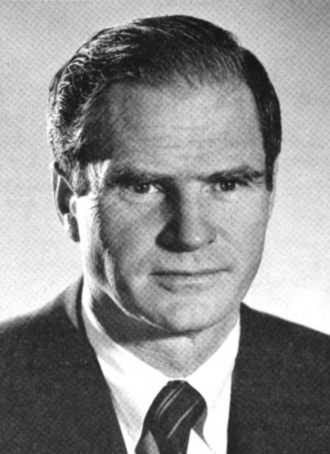

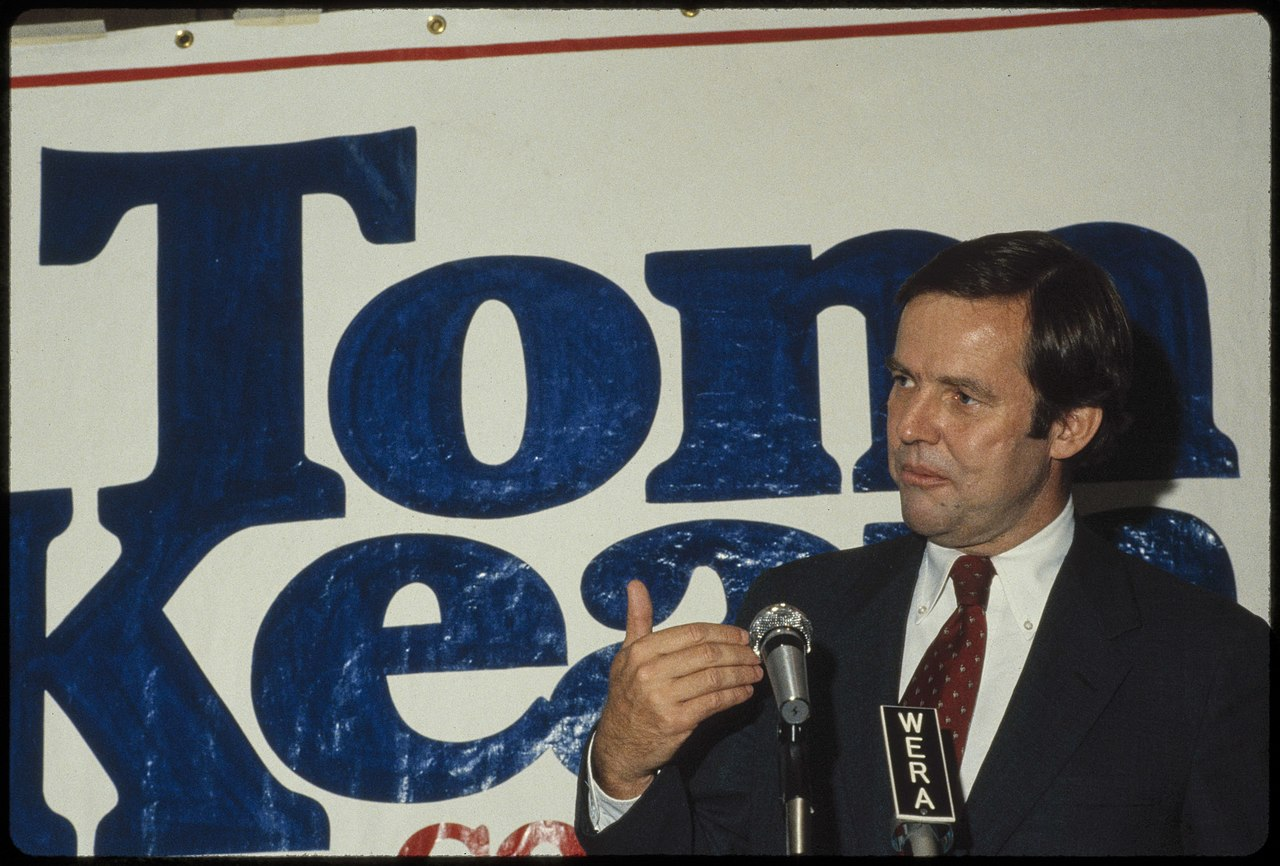

In the general election, which was framed by the national media as a referendum on President Kennedy and his agenda (in particular, his economic and tax policies), Gibson would be going up against Thomas Kean, the former Speaker of the State Assembly and runner up for the GOP nomination in 1977.

Born on April 21st, 1935 in New York City to a long line of Dutch American and New Jersey politicians, Tom Kean seemed destined for greatness. His mother was Elizabeth Stuyvesant Howard and his father, Robert Kean, was a U.S. representative from 1939 until 1959. Kean's grandfather Hamilton Fish Kean and great-uncle John Kean both served as U.S. senators from New Jersey. His second great-uncle was Hamilton Fish, a U.S. senator, governor of New York, and U.S. secretary of state. Kean is also descended from William Livingston, who was a delegate to the Continental Congress, was the first governor of New Jersey, and is considered a founding father of the state.

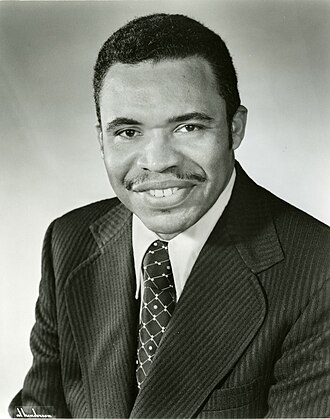

Above: Tom Kean, the Republican candidate for Governor of New Jersey in 1981.

After attending a number of elite prep schools as a boy, Kean later attended Princeton University, where he performed “groundbreaking research” on the constitution of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and earned a BA in history. He would later earn an MA (also in history) from Columbia University and become a social studies teacher at St. Mark’s, the private Episcopalian boarding school he’d attended in his adolescence. He later got involved with Republican politics in New Jersey, serving as a volunteer and surrogate for numerous state level campaigns before eventually becoming a candidate for office himself.

A moderate, dyed-in-the-wool “Romney Republican” and proud member of the so-called “Eastern Establishment” of the GOP, Kean launched his campaign with pledges to foster job creation, to clean up toxic waste sites, to reduce crime, and to preserve what he called “home rule” for his state. This was largely seen as a jab at President Kennedy and the Democrats, who seemed to stand for increased federal involvement in the nation’s economic affairs. Kean won the endorsement of former President George Bush fairly early on in the race, which enabled him to capture the nomination.

As the general election campaign got underway over the summer, both candidates sought to contrast themselves on economic issues, down to the personal contrast between Kean as the scion of a wealthy, WASP-y political dynasty and Gibson as the upstart African-American symbol of upward mobility. Gibson continued his praise of President Kennedy’s economic program and worked to link Kean to Ronald Reagan and his “dangerous ideals of ‘slash and burn’ conservatism”. Meanwhile, Kean distanced himself from the conservative wing of the GOP, even going so far as to turn down Roger Stone’s offer to work for him as a “hitman”. Stone had proposed a series of highly controversial ads filled with dog whistles that would attack Gibson and his “element”, and question whether he was “ready to lead New Jersey”. Kean feared that these ads would lead to blowback and refused to work with Stone. Instead, Kean tried to pivot, attacking Gibson as “just another tax and spend liberal”, who would do nothing to clean up the state.

As the race wore on and it became clear that President Kennedy and his policies remained popular with the people of New Jersey, Kean even tried to paint himself as the perfect candidate for “bipartisanship”. In a series of two debates held at Monmouth College and later, before the New Jersey Chamber of Commerce, Gibson decried Kean’s economic policies as “voodoo economics” (echoing former President Bush) and claimed that a Kean governorship would lead to “financial devastation, possibly even bankruptcy”. Kean accused Gibson of speaking in hyperbole and of seeking to “continue Governor Byrne’s failed regulatory policies”. Both candidates postured as being “tough on crime”, a theme that would go national the following year.

In the final days of the race, the Republican National Committee (RNC) dumped hundreds of thousands of dollars to blanket the state in television and radio ads. One famous TV ad featured Kean playing bocce, in an evident attempt to appeal to ethnically Italian voters. To counter this, Vice President Lloyd Bentsen and Senator Bill Bradley appeared frequently with Gibson at his campaign rallies. President Kennedy even made a highly-publicized appearance a few days before Election Day, in which he endorsed Gibson and delivered a rousing speech on his behalf.

In the end, the race was close, a real nail-biter.

Early returns on election night showed a narrow lead for Gibson. But the race was widely reported on as being “too close to call”. Two networks - ABC and CBS - both declared Gibson the winner, only for the Kean campaign to demand a recount, as the margin appeared to be down to less than a thousand votes. A recount was held, but in the end, the results held. By a margin of only 507 votes, Kenneth Gibson was elected Governor of New Jersey.

The result, considered a major upset despite President Kennedy’s popularity, sent shockwaves through not just the state of New Jersey, not just the Northeast, but throughout the entire nation. In a decidedly purple swing state, an unabashedly liberal Democrat (and a man of color, no less) had just defeated a moderate, Romney Republican who came from one of the most storied and well-established political dynasties in the country.

The world, as they say, had turned upside down.

Above: Ken Gibson, in his newly won office as Governor of New Jersey, Jan. 1982.

…

Above: John Dalton (R - VA), Governor of Virginia prior to the 1981 election.

If New Jersey in 1981 was a northeastern swing state in need of reform, then Virginia was a leading state of the “new South”.

Though Democratic Senator Harry F. Byrd, Jr., the state’s dominant politician, remained a steadfast opponent of the changes (namely, desegregation) sweeping the country throughout the 1960s and 70s, Virginia did, slowly but surely, come into the modern world. Most of the state’s Democrats eventually joined Johnson’s “machine” of communitarians - that is, socially conservative, fiscally liberal. Most accepted (however reluctantly) desegregation as a fait accompli, but shifted their anti-change rhetoric toward other issues, like abortion and so-called “sexual liberation”. They continued to favor “states’ rights” and “strict constitutionalism” against “federal overreach”. Voters in the South, whether Democratic or Republican, remained a very conservative demographic overall, with much of its population comprising white, evangelical protestants, who still made up strong contingents of both parties.

This was only part of the picture in Virginia, however.

By 1981, much of the Old Dominion’s burgeoning growth and prosperity was centered in the northern part of the state. This was chiefly due to employment related to Federal government agencies and defense, as well as an increase in technology in Northern Virginia. The north’s proximity to DC shifted its demographics toward becoming increasingly wealthy, increasingly educated, and increasingly liberal (at least, socially). The suburbs outside of major cities like Richmond also exploded. Thus, a divide formed between the cosmopolitan north of the state and the more traditionally “southern” south, west, and east.

With Governor John Dalton being term-limited (Virginia does allow for a person to serve multiple terms, but they cannot be consecutive), the Republicans obviously hoped to retain the governor’s mansion and maintain their in-roads into the South. They nominated the state’s Attorney General, 39 year old Marshall Coleman of Staunton.

Coleman’s father - William Warren Coleman - had been a factory worker-turned-minister and instilled in his son both a strong, protestant work ethic and devout religious beliefs. Those beliefs would be shaken, however, when on January 15th, 1952, a nine year old Coleman was shocked to find his father, who had become badly injured in an automobile accident the previous year, had committed suicide in their basement. The event was said to have deeply traumatized the boy and left a profound impact upon his life.

Nonetheless, Coleman pressed forward with his education. He graduated from the University of Virginia with a B.A., in 1964, and received his J.D. from the University of Virginia School of Law in 1970. Between his studies in Charlottesville, Coleman served in the United States Marine Corps (1966–1969) including 13 months as an “advisor” on the ground in Vietnam. Upon admission to the Virginia bar, Coleman practiced law, as well as almost immediately ran for public office. In 1973, Coleman won election to the Virginia House of Delegates. Four years later, in 1977, he was elected the state’s Attorney General at just 35 years of age. He became the first Republican to hold that position since Reconstruction. While Attorney General, he argued (and lost) four cases before the US Supreme Court. Most of these concerned cases involving habeas corpus.

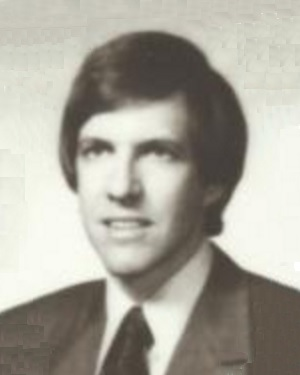

Opposing Coleman in the 1981 general election was a fellow marine - Lt. Governor Chuck Robb, a Democrat. Virginia separately elects its governors and lt. Governors, rather than having them serve as a combined ticket.

Charles “Chuck” Robb was born June 26th, 1939 in Phoenix, Arizona, but grew up in the Mount Vernon area of Fairfax County, Virginia. After graduating from Mount Vernon high school, Robb attended Cornell University in Upstate New York before earning a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1961, where he was a member of the Chi Phi Fraternity

A United States Marine Corps veteran and honor graduate of Quantico, Robb became a White House social aide. It was there that he met and eventually married Lynda Johnson, the daughter of then-U.S. Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson in a service celebrated by the Right Reverend Gerald Nicholas McAllister. Robb went on to serve a tour of duty in Cambodia, where he commanded Company I of 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines in combat, and was awarded the Bronze Star and Cambodia Gallantry Cross with Star. Following his promotion to the rank of major, he was attached to the Logistics section (G-4), 1st Marine Division.

In 1972, he worked as an aide on his father-in-law’s presidential campaign. He was bitterly disappointed when LBJ failed to capture the White House. But Robb went back to school, earning a JD from the University of Virginia Law School in 1973, and clerked for John D. Butzner, Jr., a judge on the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. Afterwards he resided in McLean, Virginia and entered private practice. Robb eventually became active in Virginia politics as a Democrat, winning election as Lieutenant Governor in 1977. As the only Democratic to win statewide office that year, Robb became the state party’s de facto leader as well.

Despite his father-in-law’s success at building a “new Southern machine” in the early 1970s, Virginia’s Democratic Party had, by 1977, been anemic and rudderless for the better part of a decade. Republicans had occupied the governor’s mansion since 1969 and the aforementioned Harry F. Byrd, US Senator, repeatedly waffled on whether he even wanted to remain a Democrat at all, what with “how far left” the national party had gone.

Thus, Robb, who was easily nominated for governor in ‘81, had a number of choices to make. He was essentially given free reign to shape the Virginia state party as he saw fit. Electorally, he had to set a strategy. Which groups within the state would he try to appeal to? Which regions? In the end, Robb rejected the “communitarian” archetype that so many Southern Democrats were embracing, in favor of a platform that more accurately represented his personally-held political beliefs.

Robb was a moderate Democrat, but not in the manner typical for the South. He was fiscally conservative, favoring balanced budgets and pro-business policies and socially progressive, championing not only civil rights, but pro-choice on abortion and in favor of toleration and liberation for LGBT+ Americans. He made it his mission, beginning in 1977, to build a more progressive Democratic Party in Virginia than the one that had ruled it for decades before. Turning not just to his father-in-law, but also to Terry Sanford and Ralph Yarborough for inspiration, Robb made himself the candidate for the young and the liberal throughout the state.

This definitely played to his benefit in 1981. Coleman ran as a run of the mill conservative Republican, which helped Robb stand out and appeal to both liberals and moderates. Independents in particular seemed to favor Robb over Coleman. Coleman attempted to court the support of the state’s sizable evangelical population by making hay out of Robb’s support of one issue in particular - repealing Virginia’s statewide “anti-sodomy” laws. Unfortunately for him, this plan largely backfired.

During a debate between the two candidates for governor, Robb eloquently stated, “The fact that our hearts don't speak in the same way is not cause or justification to discriminate.” Robb did not argue for gay marriage or full equality (such a position would have been seen as "radical" for the time), but to even openly support toleration of gay and lesbian people in the South in 1981 was seen as quite the progressive step forward.

As in the race in New Jersey, both candidates positioned themselves as “tough on crime”, with Robb going so far as to state his “openness” to the idea of being the first governor of Virginia in 25 years to use the death penalty for capital crimes. Again, this portented the national mood on “law and order” issues that the national party would seek to address the following year.

On election night, Chuck Robb was elected the 64th Governor of Virginia, winning 53.5% of the vote to Coleman’s 46.4%. This represented a margin of some 100,000 votes. Robb’s victory, when taken with Gibson’s in New Jersey, seemed to demonstrate strong national support for President Kennedy and the Democrats at the tail end of his first year in office. The people’s party hoped to maintain that edge into 1982 and the midterm elections.

Meanwhile, the Republicans continued their tail-spin. Once again frustrated by the robust New Frontier Coalition, the GOP took the defeats in Virginia, and especially in New Jersey, rather hard. Tom Kean had seemed the perfect candidate, especially when put up against Kenneth Gibson. The idea that “white ethnics” (Italian-Americans, Polish-Americans, etc.) had chosen an African-American candidate over a white one ran counter to the prevailing political calculus of the day. Indeed, Republicans came to believe that if they wanted to stand a snowball’s chance in Hell of ever regaining political relevance, then they needed to expand their electoral coalition beyond just the well-to-do and suburbanites worried about inflation. Beyond winning back “Kennedy Republicans” as they came to be known, the party needed to find wedge issues that could cleave off portions of the Democrats’ support.

Two schools of thought emerged over the next several years on how to achieve this.

One, advocated for by the liberal wing of the party, called for moderate economic policies, the “Dime Store New Deal” detested by Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan, but embraced by Dwight Eisenhower, George Romney, and George Bush, the last three Republicans to be elected to the Presidency. By courting support of moderates and independents among college-educated voters, these “Romney Republicans” claimed, they could undercut Democratic support in the Northeast, the Midwest, and on the West Coast. It was in those regions that these Republicans had the most cache. This school of thought seems like it could have helped in Virginia, which appeared to be more liberal socially than previously thought. But it seemed refuted by the results in New Jersey, where Kean, a perfect example of this type of Republican, had been edged out by Gibson.

The other approach, favored by the party’s conservative wing (now led by Senators Paul Laxalt of Nevada and Jesse Helms of North Carolina, among others) called for a hard tack to the right on social issues, to cleave off socially conservative voters. It held the most support in the South and West. But it was also rapidly gaining support in the Midwest as well. Ronald Reagan’s defeat to Bob Kennedy in 1980 should have been the death knell for this wing of the party. Reagan was, after all, conservatism’s best known and most well-liked spokesman in the United States. But the party base continued to clamor for it. And conservatives, feeling abandoned by the Democrats, still sought to move the GOP right to find a new home.

For now, the Republicans remained badly divided, to the benefit of the Democrats.

Next time on Blue Skies in Camelot: Pop Culture in 1981

Last edited:

Great update, Mr. President. It seems like an almighty battle for the soul of the GOP is brewing. It would be nice if the evangelicals and Reaganites could bugger off and found a new party named "American Liberty Party" or whatever and let the "Party of Lincoin" be great again.Chapter 153 - Take it on the Run: 1981 Off-Year Elections in the United States

Above: Kenneth Gibson (D - NJ) and Chuck Robb (D - VA), Democratic nominees for governor of New Jersey and Virginia in 1981, respectively.

“You take it on the run, baby

If that's the way you want it, baby

Then I don't want you around

I don't believe it

Not for a minute

You're under the gun

So you take it on the run” - “Take it on the Run” by REO Speedwagon

“Wherever America is going, New Jersey will get there first.” - Ken Gibson, on the campaign trail

“The fact that our hearts don't speak in the same way is not cause or justification to discriminate.” - Chuck Robb, explaining his support for decriminalizing “sodomy” in the state of Virginia

Though (perhaps understandably) not as widely covered as the midterms, off-year elections are sometimes treated as bell-weathers for the popularity of the president and their party on the national level. For the people of the states of New Jersey and Virginia, of course, there are chances to vote on who will occupy the governor’s mansions of their respective states. For national political wonks, they are also a testing-ground for campaign messaging and strategy. In 1981, both the Garden State and the Old Dominion were due for new chief executives due to both having term-limited incumbents.

Above: Brendan Byrne (D - NJ), outgoing governor in 1981, AKA “the man that couldn’t be bought”.

In New Jersey, that incumbent was Brendan Byrne. A Democrat, originally from West Orange, Byrne first rose to prominence as a prosecutor in the 1960s. While in that position, he was referenced by mobsters operating in the state who’d been wiretapped by the FBI as “the man who couldn’t be bought”, due to his high ethical standards. That comment, combined with an environment in the Tri-State area at the time that considered corruption a critical issue propelled Byrne to statewide fame. In 1973, he was elected Governor, using his “couldn’t be bought” title as a campaign slogan. During his first term, Byrne signed the state’s first income-tax into law, violating a campaign pledge not to do so. Despite a spirited primary challenge and a hard-fought general election in 1977, in which he was widely expected to lose, Byrne defied the odds and won a second term. He spent the next four years overseeing the opening of the state’s first gambling casinos in Atlantic City, increasing openness and transparency in the state government, and preserving a large majority of woodlands and wildlife areas in the state by restricting development. At the tail end of his second term, Byrne’s popularity had rebounded somewhat, but he was leaving office a highly polarizing figure. Conservatives and moderates were still furious that he’d broken his “no income tax” pledge and believed that his restriction on development had cost the state jobs.

The field of Democratic candidates to succeed Byrne was quite crowded. Because the governor declined to name any preferred successor early on, the candidates staked out bold stances on the issues of the day to try and differentiate themselves. Unsurprisingly, they also attempted to tie themselves strongly to President Robert Kennedy, whose approval ratings (in the wake of the attempt on his life by Mark Chapman) hovered around 60% nationally. None of the candidates had a close personal relationship with the president, but that did not stop them from claiming one anyway. Some of the major candidates in the Democratic primary included:

- Herbert J. Buehler, former state senator from Point Pleasant Beach

- John J. Degnan, New Jersey Attorney General

- Frank J. Dodd, state senator from West Orange

- James Florio, U.S. Representative from Runnemede

- Kenneth A. Gibson, Mayor of Newark

- William J. Hamilton, state senator from New Brunswick

- Ann Klein, Human Services Commissioner, former Assemblywoman from Morristown, and candidate for governor in 1973

- Barbara McConnell, state assemblywoman from Flemington

Among the candidates, Jim Florio had run against Byrne in the Democratic primary four years prior, and thus enjoyed the most name recognition throughout the state. Florio staked out his ‘81 campaign on two key issues: a renewed pledge for no new taxes; and being the only Democratic candidate to receive an endorsement from the National Rifle Association. “Pro-gun” and “anti-crime”, Florio vowed to continue to fight corruption in Trenton. His campaign suffered, however, as he remained in Washington, D.C., serving out his term in Congress.

Florio’s absence and Byrne’s initial refusal to back any one candidate (he eventually endorsed Degnan, but by then the impact of the endorsement was probably minimal) stood to benefit the rest of the field, of course. Among the other candidates, one in particular was able to leverage this vacuum in the media and on the stump to his advantage.

Kenneth Allen Gibson, born May 15th, 1932, was the 36th Mayor of Newark, New Jersey, a position which he had held since first being elected back in 1970. Thanks to that position, Gibson became the first African American to serve as mayor of a major city in the Northeastern United States.

Above: Ken Gibson on the cover of Newsweek.

Gibson was a Newark native. As a teenager, he attended Central High School, where he played with a dance band after school to bring in income needed for his family. After graduation, he studied civil engineering in college, but financial challenges forced him to drop out of school after a few months in school. He then worked in a factory, served in the military and later worked for the New Jersey Highway Department, completing his engineering degree in 1963 by taking night classes.

In 1970, Gibson won election as Mayor as a reformer. At the time, Gibson noted that, “Newark may be the most decayed and financially crippled city in the nation.” He alleged that the previous mayor, Hugh Addonizio, had been “hopelessly corrupt”. Sure enough, shortly after Gibson was elected, Addonizio was convicted of conspiracy and extortion.

Gibson was also seen as a representative of the city’s sizable African-American population, many of whom were migrants or whose parents or grandparents had come North in the Great Migration. The city's industrial power had diminished sharply, however. Deindustrialization since the 1950s cost tens of thousands of jobs when African Americans were still arriving from the South looking for better opportunities than in their former communities. Combined with forces of suburbanization and racial tensions, the city encountered problems similar to those of other major industrial cities of the North and Midwest in the 1960s - increasing poverty and dysfunction for families left without employment. The city was scarred by race riots in 1967, three years before Gibson took office. Many businesses and residents left the city after the riots and were reluctant to return.

After being re-elected in 1974, Gibson went on to become the first African-American president of the United States Conference of Mayors, serving in that role for just over a year from 1976 - 1977.

Though he was viewed by many, both within Newark and beyond as a symbol of hope and the possibility of change, some of his supporters did feel alienated by some of his policy decisions while in office. Namely, in a bid to bring businesses and jobs back to Newark, he approved tax breaks and sweetheart deals to state and corporate interests, and increased funding for the city’s police force, even as its social services saw their budgets’ slashed due to a shrinking tax base.

Nevertheless, he won a third term in 1978 and by 1980, for most, the bloom was very much still on the rose, so to speak. 49 years old in 1981, Gibson announced his candidacy for governor by claiming that he was “the candidate for progress”. He barnstormed the state, delivering impassioned speeches, and calling on his fellow Garden Staters to embrace the “change” that he claimed to represent. For many, the unspoken nature of that “change” was, largely, the color of Gibson’s skin.

Gibson aimed to be the first African-American governor not just in New Jersey’s history, but across the Northeast in general. “If Charles Evers can be elected the United States Senator from Mississippi on the Democratic ticket,” Gibson privately told his staff. “Then I believe that the people of New Jersey may be ready for a man of color as governor.” That said, Gibson was also careful not to paint himself as the “black candidate” for that office. He feared (unfortunately, justifiably) that tying himself too closely to that label could backfire on him. Instead, he spoke in more vague terms of “change” and “progress” and “a new generation of leadership”. In that way, he largely adapted the Kennedy brand of optimism and hope for the future.

Across the state, people’s eyes turned to Gibson. The crowded nature of the primary played to his advantage as well. By cultivating a loyal, dedicated following, Gibson outshone several of the less well-known candidates, and set himself up to challenge the “absentee candidate” - Florio. When the Democratic primary was held, on June 2nd, 1981, the number of candidates was thought to be the deciding factor.

With just 26.2% of the vote, Ken Gibson, Mayor of Newark, managed to eke out a win over Florio, who scored 25.4%, as well as all the other candidates. Though hardly a decisive victory, Gibson would be the Democratic nominee for governor of New Jersey in 1981. In a massive rally in his hometown, Gibson celebrated with his wife, Camille, and a crowd of devoted supporters.

In the general election, which was framed by the national media as a referendum on President Kennedy and his agenda (in particular, his economic and tax policies), Gibson would be going up against Thomas Kean, the former Speaker of the State Assembly and runner up for the GOP nomination in 1977.

Born on April 21st, 1935 in New York City to a long line of Dutch American and New Jersey politicians, Tom Kean seemed destined for greatness. His mother was Elizabeth Stuyvesant Howard and his father, Robert Kean, was a U.S. representative from 1939 until 1959. Kean's grandfather Hamilton Fish Kean and great-uncle John Kean both served as U.S. senators from New Jersey. His second great-uncle was Hamilton Fish, a U.S. senator, governor of New York, and U.S. secretary of state. Kean is also descended from William Livingston, who was a delegate to the Continental Congress, was the first governor of New Jersey, and is considered a founding father of the state.

Above: Tom Kean, the Republican candidate for Governor of New Jersey in 1981.

After attending a number of elite prep schools as a boy, Kean later attended Princeton University, where he performed “groundbreaking research” on the constitution of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and earned a BA in history. He would later earn an MA (also in history) from Columbia University and become a social studies teacher at St. Mark’s, the private Episcopalian boarding school he’d attended in his adolescence. He later got involved with Republican politics in New Jersey, serving as a volunteer and surrogate for numerous state level campaigns before eventually becoming a candidate for office himself.

A moderate, dyed-in-the-wool “Romney Republican” and proud member of the so-called “Eastern Establishment” of the GOP, Kean launched his campaign with pledges to foster job creation, to clean up toxic waste sites, to reduce crime, and to preserve what he called “home rule” for his state. This was largely seen as a jab at President Kennedy and the Democrats, who seemed to stand for increased federal involvement in the nation’s economic affairs. Kean won the endorsement of former President George Bush fairly early on in the race, which enabled him to capture the nomination.

As the general election campaign got underway over the summer, both candidates sought to contrast themselves on economic issues, down to the personal contrast between Kean as the scion of a wealthy, WASP-y political dynasty and Gibson as the upstart African-American symbol of upward mobility. Gibson continued his praise of President Kennedy’s economic program and worked to link Kean to Ronald Reagan and his “dangerous ideals of ‘slash and burn’ conservatism”. Meanwhile, Kean distanced himself from the conservative wing of the GOP, even going so far as to turn down Roger Stone’s offer to work for him as a “hitman”. Stone had proposed a series of highly controversial ads filled with dog whistles that would attack Gibson and his “element”, and question whether he was “ready to lead New Jersey”. Kean feared that these ads would lead to blowback and refused to work with Stone. Instead, Kean tried to pivot, attacking Gibson as “just another tax and spend liberal”, who would do nothing to clean up the state.

As the race wore on and it became clear that President Kennedy and his policies remained popular with the people of New Jersey, Kean even tried to paint himself as the perfect candidate for “bipartisanship”. In a series of two debates held at Monmouth College and later, before the New Jersey Chamber of Commerce, Gibson decried Kean’s economic policies as “voodoo economics” (echoing former President Bush) and claimed that a Kean governorship would lead to “financial devastation, possibly even bankruptcy”. Kean accused Gibson of speaking in hyperbole and of seeking to “continue Governor Byrne’s failed regulatory policies”. Both candidates postured as being “tough on crime”, a theme that would go national the following year.

In the final days of the race, the Republican National Committee (RNC) dumped hundreds of thousands of dollars to blanket the state in television and radio ads. One famous TV ad featured Kean playing bocce, in an evident attempt to appeal to ethnically Italian voters. To counter this, Vice President Lloyd Bentsen and Senator Bill Bradley appeared frequently with Gibson at his campaign rallies. President Kennedy even made a highly-publicized appearance a few days before Election Day, in which he endorsed Gibson and delivered a rousing speech on his behalf.

In the end, the race was close, a real nail-biter.

Early returns on election night showed a narrow lead for Gibson. But the race was widely reported on as being “too close to call”. Two networks - ABC and CBS - both declared Gibson the winner, only for the Kean campaign to demand a recount, as the margin appeared to be down to less than a thousand votes. A recount was held, but in the end, the results held. By a margin of only 507 votes, Kenneth Gibson was elected Governor of New Jersey.

The result, considered a major upset despite President Kennedy’s popularity, sent shockwaves through not just the state of New Jersey, not just the Northeast, but throughout the entire nation. In a decidedly purple swing state, an unabashedly liberal Democrat (and a man of color, no less) had just defeated a moderate, Romney Republican who came from one of the most storied and well-established political dynasties in the country.

The world, as they say, had turned upside down.

Above: Ken Gibson, in his newly won office as Governor of New Jersey, Jan. 1982.

…

Above: John Dalton (R - VA), Governor of Virginia prior to the 1981 election.

If New Jersey in 1981 was a northeastern swing state in need of reform, then Virginia was a leading state of the “new South”.

Though Democratic Senator Harry F. Byrd, Jr., the state’s dominant politician, remained a steadfast opponent of the changes (namely, desegregation) sweeping the country throughout the 1960s and 70s, Virginia did, slowly but surely, come into the modern world. Most of the state’s Democrats eventually joined Johnson’s “machine” of communitarians - that is, socially conservative, fiscally liberal. Most accepted (however reluctantly) desegregation as a fait accompli, but shifted their anti-change rhetoric toward other issues, like abortion and so-called “sexual liberation”. They continued to favor “states’ rights” and “strict constitutionalism” against “federal overreach”. Voters in the South, whether Democratic or Republican, remained a very conservative demographic overall, with much of its population comprising white, evangelical protestants, who still made up strong contingents of both parties.

This was only part of the picture in Virginia, however.

By 1981, much of the Old Dominion’s burgeoning growth and prosperity was centered in the northern part of the state, particularly the Hampton Roads region. This was chiefly due to employment related to Federal government agencies and defense, as well as an increase in technology in Northern Virginia. The north’s proximity to DC shifted its demographics toward becoming increasingly wealthy, increasingly educated, and increasingly liberal (at least, socially). The suburbs outside of major cities like Richmond also exploded. Thus, a divide formed between the cosmopolitan north of the state and the more traditionally “southern” south, west, and east.

With Governor John Dalton being term-limited, the Republicans obviously hoped to retain the governor’s mansion and maintain their in-roads into the South. They nominated the state’s Attorney General, 39 year old Marshall Coleman of Staunton.

Coleman’s father - William Warren Coleman - had been a factory worker-turned-minister and instilled in his son both a strong, protestant work ethic and devout religious beliefs. Those beliefs would be shaken, however, when on January 15th, 1952, a nine year old Coleman was shocked to find his father, who had become badly injured in an automobile accident the previous year, had committed suicide in their basement. The event was said to have deeply traumatized the boy and left a profound impact upon his life.

Nonetheless, Coleman pressed forward with his education. He graduated from the University of Virginia with a B.A., in 1964, and received his J.D. from the University of Virginia School of Law in 1970. Between his studies in Charlottesville, Coleman served in the United States Marine Corps (1966–1969) including 13 months as an “advisor” on the ground in Vietnam. Upon admission to the Virginia bar, Coleman practiced law, as well as almost immediately ran for public office. In 1973, Coleman won election to the Virginia House of Delegates. Four years later, in 1977, he was elected the state’s Attorney General at just 35 years of age. He became the first Republican to hold that position since Reconstruction. While Attorney General, he argued (and lost) four cases before the US Supreme Court. Most of these concerned cases involving habeas corpus.

Opposing Coleman in the 1981 general election was a fellow marine - Lt. Governor Chuck Robb, a Democrat. Virginia separately elects its governors and lt. Governors, rather than having them serve as a combined ticket.

Above: Chuck Robb, then Lt. Governor of Virginia, speaks to guests at a luncheon during the Virginia General Assembly's tour of Marine Corps Base Quantico on February 1st, 1981.

Charles “Chuck” Robb was born June 26th, 1939 in Phoenix, Arizona, but grew up in the Mount Vernon area of Fairfax County, Virginia. After graduating from Mount Vernon high school, Robb attended Cornell University in Upstate New York before earning a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1961, where he was a member of the Chi Phi Fraternity

A United States Marine Corps veteran and honor graduate of Quantico, Robb became a White House social aide. It was there that he met and eventually married Lynda Johnson, the daughter of then-U.S. Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson in a service celebrated by the Right Reverend Gerald Nicholas McAllister. Robb went on to serve a tour of duty in Cambodia, where he commanded Company I of 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines in combat, and was awarded the Bronze Star and Cambodia Gallantry Cross with Star. Following his promotion to the rank of major, he was attached to the Logistics section (G-4), 1st Marine Division.

In 1972, he worked as an aide on his father-in-law’s presidential campaign. He was bitterly disappointed when LBJ failed to capture the White House. But Robb went back to school, earning a JD from the University of Virginia Law School in 1973, and clerked for John D. Butzner, Jr., a judge on the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. Afterwards he resided in McLean, Virginia and entered private practice. Robb eventually became active in Virginia politics as a Democrat, winning election as Lieutenant Governor in 1977. As the only Democratic to win statewide office that year, Robb became the state party’s de facto leader as well.

Despite his father-in-law’s success at building a “new Southern machine” in the early 1970s, Virginia’s Democratic Party had, by 1977, been anemic and rudderless for the better part of a decade. Republicans had occupied the governor’s mansion since 1969 and the aforementioned Harry F. Byrd, US Senator, repeatedly waffled on whether he even wanted to remain a Democrat at all, what with “how far left” the national party had gone.

Thus, Robb, who was easily nominated for governor in ‘81, had a number of choices to make. He was essentially given free reign to shape the Virginia state party as he saw fit. Electorally, he had to set a strategy. Which groups within the state would he try to appeal to? Which regions? In the end, Robb rejected the “communitarian” archetype that so many Southern Democrats were embracing, in favor of a platform that more accurately represented his personally-held political beliefs.

Robb was a moderate Democrat, but not in the manner typical for the South. He was fiscally conservative, favoring balanced budgets and pro-business policies and socially progressive, championing not only civil rights, but pro-choice on abortion and in favor of toleration and liberation for LGBT+ Americans. He made it his mission, beginning in 1977, to build a more progressive Democratic Party in Virginia than the one that had ruled it for decades before. Turning not just to his father-in-law, but also to Terry Sanford and Ralph Yarborough for inspiration, Robb made himself the candidate for the young and the liberal throughout the state.

This definitely played to his benefit in 1981. Coleman ran as a run of the mill conservative Republican, which helped Robb stand out and appeal to both liberals and moderates. Independents in particular seemed to favor Robb over Coleman. Coleman attempted to court the support of the state’s sizable evangelical population by making hay out of Robb’s support of one issue in particular - repealing Virginia’s statewide “anti-sodomy” laws. Unfortunately for him, this plan largely backfired.

During a debate between the two candidates for governor, Robb eloquently stated, “The fact that our hearts don't speak in the same way is not cause or justification to discriminate.” Robb did not argue for gay marriage or full equality (such a position would have been seen as "radical" for the time), but to even openly support toleration of gay and lesbian people in the South in 1981 was seen as quite the progressive step forward.

As in the race in New Jersey, both candidates positioned themselves as “tough on crime”, with Robb going so far as to state his “openness” to the idea of being the first governor of Virginia in 25 years to use the death penalty for capital crimes. Again, this portented the national mood on “law and order” issues that the national party would seek to address the following year.

On election night, Chuck Robb was elected the 64th Governor of Virginia, winning 53.5% of the vote to Coleman’s 46.4%. This represented a margin of some 100,000 votes. Robb’s victory, when taken with Gibson’s in New Jersey, seemed to demonstrate strong national support for President Kennedy and the Democrats at the tail end of his first year in office. The people’s party hoped to maintain that edge into 1982 and the midterm elections.

Meanwhile, the Republicans continued their tail-spin. Once again frustrated by the robust New Frontier Coalition, the GOP took the defeats in Virginia, and especially in New Jersey, rather hard. Tom Kean had seemed the perfect candidate, especially when put up against Kenneth Gibson. The idea that “white ethnics” (Italian-Americans, Polish-Americans, etc.) had chosen an African-American candidate over a white one ran counter to the prevailing political calculus of the day. Indeed, Republicans came to believe that if they wanted to stand a snowball’s chance in Hell of ever regaining political relevance, then they needed to expand their electoral coalition beyond just the well-to-do and suburbanites worried about inflation. Beyond winning back “Kennedy Republicans” as they came to be known, the party needed to find wedge issues that could cleave off portions of the Democrats’ support.

Two schools of thought emerged over the next several years on how to achieve this.

One, advocated for by the liberal wing of the party, called for moderate economic policies, the “Dime Store New Deal” detested by Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan, but embraced by Dwight Eisenhower, George Romney, and George Bush, the last three Republicans to be elected to the Presidency. By courting support of moderates and independents among college-educated voters, these “Romney Republicans” claimed, they could undercut Democratic support in the Northeast, the Midwest, and on the West Coast. It was in those regions that these Republicans had the most cache. This school of thought seems like it could have helped in Virginia, which appeared to be more liberal socially than previously thought. But it seemed refuted by the results in New Jersey, where Kean, a perfect example of this type of Republican, had been edged out by Gibson.

The other approach, favored by the party’s conservative wing (now led by Senators Paul Laxalt of Arizona and Jesse Helms of North Carolina, among others) called for a hard tack to the right on social issues, to cleave off socially conservative voters. It held the most support in the South and West. But it was also rapidly gaining support in the Midwest as well. Ronald Reagan’s defeat to Bob Kennedy in 1980 should have been the death knell for this wing of the party. Reagan was, after all, conservatism’s best known and most well-liked spokesman in the United States. But the party base continued to clamor for it. And conservatives, feeling abandoned by the Democrats, still sought to move the GOP right to find a new home.

For now, the Republicans remained badly divided, to the benefit of the Democrats.

Next time on Blue Skies in Camelot: Pop Culture in 1981

Also, will Anderson's National Unity Party influence the Republicans' internal ideological conflict?

Last edited:

Great to see the Dems win in New Jersey and Virginia, although I am a bit surprised by the Jersey victory. But it’s certainly interesting to see what way the republicans go. One would imagine a more liberal route given their past successes with that route, but you never know

Please make sure this asshole lands in jail ttlMeanwhile, Kean distanced himself from the conservative wing of the GOP, even going so far as to turn down Roger Stone’s offer to work for him as a “hitman”. Stone had proposed a series of highly controversial ads filled with dog whistles that would attack Gibson and his “element”, and question whether he was “ready to lead New Jersey”. Kean feared that these ads would lead to blowback and refused to work with Stone. Instead, Kean tried to pivot, attacking Gibson as “just another tax and spend liberal”, who would do nothing to clean up the state.

Very nice. Pleas make sure Stone ends up in prison, so he can't screw with GOP politics any more.

Great chapter. I like the changes you made, New Jersey has it's first African American governor and Virginia is becoming more progressive than people originally thought. GOP is battling for it's soul, hopefully the moderate wing comes out on top. Can't wait to see what you come up with for the pop culture.Chapter 153 - Take it on the Run: 1981 Off-Year Elections in the United States

Above: Kenneth Gibson (D - NJ) and Chuck Robb (D - VA), Democratic nominees for governor of New Jersey and Virginia in 1981, respectively.

“You take it on the run, baby

If that's the way you want it, baby

Then I don't want you around

I don't believe it

Not for a minute

You're under the gun

So you take it on the run” - “Take it on the Run” by REO Speedwagon

“Wherever America is going, New Jersey will get there first.” - Ken Gibson, on the campaign trail

“The fact that our hearts don't speak in the same way is not cause or justification to discriminate.” - Chuck Robb, explaining his support for decriminalizing “sodomy” in the state of Virginia

Though (perhaps understandably) not as widely covered as the midterms, off-year elections are sometimes treated as bell-weathers for the popularity of the president and their party on the national level. For the people of the states of New Jersey and Virginia, of course, there are chances to vote on who will occupy the governor’s mansions of their respective states. For national political wonks, they are also a testing-ground for campaign messaging and strategy. In 1981, both the Garden State and the Old Dominion were due for new chief executives due to both having term-limited incumbents.

Above: Brendan Byrne (D - NJ), outgoing governor in 1981, AKA “the man that couldn’t be bought”.

In New Jersey, that incumbent was Brendan Byrne. A Democrat, originally from West Orange, Byrne first rose to prominence as a prosecutor in the 1960s. While in that position, he was referenced by mobsters operating in the state who’d been wiretapped by the FBI as “the man who couldn’t be bought”, due to his high ethical standards. That comment, combined with an environment in the Tri-State area at the time that considered corruption a critical issue propelled Byrne to statewide fame. In 1973, he was elected Governor, using his “couldn’t be bought” title as a campaign slogan. During his first term, Byrne signed the state’s first income-tax into law, violating a campaign pledge not to do so. Despite a spirited primary challenge and a hard-fought general election in 1977, in which he was widely expected to lose, Byrne defied the odds and won a second term. He spent the next four years overseeing the opening of the state’s first gambling casinos in Atlantic City, increasing openness and transparency in the state government, and preserving a large majority of woodlands and wildlife areas in the state by restricting development. At the tail end of his second term, Byrne’s popularity had rebounded somewhat, but he was leaving office a highly polarizing figure. Conservatives and moderates were still furious that he’d broken his “no income tax” pledge and believed that his restriction on development had cost the state jobs.

The field of Democratic candidates to succeed Byrne was quite crowded. Because the governor declined to name any preferred successor early on, the candidates staked out bold stances on the issues of the day to try and differentiate themselves. Unsurprisingly, they also attempted to tie themselves strongly to President Robert Kennedy, whose approval ratings (in the wake of the attempt on his life by Mark Chapman) hovered around 60% nationally. None of the candidates had a close personal relationship with the president, but that did not stop them from claiming one anyway. Some of the major candidates in the Democratic primary included:

- Herbert J. Buehler, former state senator from Point Pleasant Beach

- John J. Degnan, New Jersey Attorney General

- Frank J. Dodd, state senator from West Orange

- James Florio, U.S. Representative from Runnemede

- Kenneth A. Gibson, Mayor of Newark

- William J. Hamilton, state senator from New Brunswick

- Ann Klein, Human Services Commissioner, former Assemblywoman from Morristown, and candidate for governor in 1973

- Barbara McConnell, state assemblywoman from Flemington

Among the candidates, Jim Florio had run against Byrne in the Democratic primary four years prior, and thus enjoyed the most name recognition throughout the state. Florio staked out his ‘81 campaign on two key issues: a renewed pledge for no new taxes; and being the only Democratic candidate to receive an endorsement from the National Rifle Association. “Pro-gun” and “anti-crime”, Florio vowed to continue to fight corruption in Trenton. His campaign suffered, however, as he remained in Washington, D.C., serving out his term in Congress.

Florio’s absence and Byrne’s initial refusal to back any one candidate (he eventually endorsed Degnan, but by then the impact of the endorsement was probably minimal) stood to benefit the rest of the field, of course. Among the other candidates, one in particular was able to leverage this vacuum in the media and on the stump to his advantage.

Kenneth Allen Gibson, born May 15th, 1932, was the 36th Mayor of Newark, New Jersey, a position which he had held since first being elected back in 1970. Thanks to that position, Gibson became the first African American to serve as mayor of a major city in the Northeastern United States.

Above: Ken Gibson on the cover of Newsweek.

Gibson was a Newark native. As a teenager, he attended Central High School, where he played with a dance band after school to bring in income needed for his family. After graduation, he studied civil engineering in college, but financial challenges forced him to drop out of school after a few months in school. He then worked in a factory, served in the military and later worked for the New Jersey Highway Department, completing his engineering degree in 1963 by taking night classes.

In 1970, Gibson won election as Mayor as a reformer. At the time, Gibson noted that, “Newark may be the most decayed and financially crippled city in the nation.” He alleged that the previous mayor, Hugh Addonizio, had been “hopelessly corrupt”. Sure enough, shortly after Gibson was elected, Addonizio was convicted of conspiracy and extortion.

Gibson was also seen as a representative of the city’s sizable African-American population, many of whom were migrants or whose parents or grandparents had come North in the Great Migration. The city's industrial power had diminished sharply, however. Deindustrialization since the 1950s cost tens of thousands of jobs when African Americans were still arriving from the South looking for better opportunities than in their former communities. Combined with forces of suburbanization and racial tensions, the city encountered problems similar to those of other major industrial cities of the North and Midwest in the 1960s - increasing poverty and dysfunction for families left without employment. The city was scarred by race riots in 1967, three years before Gibson took office. Many businesses and residents left the city after the riots and were reluctant to return.

After being re-elected in 1974, Gibson went on to become the first African-American president of the United States Conference of Mayors, serving in that role for just over a year from 1976 - 1977.

Though he was viewed by many, both within Newark and beyond as a symbol of hope and the possibility of change, some of his supporters did feel alienated by some of his policy decisions while in office. Namely, in a bid to bring businesses and jobs back to Newark, he approved tax breaks and sweetheart deals to state and corporate interests, and increased funding for the city’s police force, even as its social services saw their budgets’ slashed due to a shrinking tax base.

Nevertheless, he won a third term in 1978 and by 1980, for most, the bloom was very much still on the rose, so to speak. 49 years old in 1981, Gibson announced his candidacy for governor by claiming that he was “the candidate for progress”. He barnstormed the state, delivering impassioned speeches, and calling on his fellow Garden Staters to embrace the “change” that he claimed to represent. For many, the unspoken nature of that “change” was, largely, the color of Gibson’s skin.

Gibson aimed to be the first African-American governor not just in New Jersey’s history, but across the Northeast in general. “If Charles Evers can be elected the United States Senator from Mississippi on the Democratic ticket,” Gibson privately told his staff. “Then I believe that the people of New Jersey may be ready for a man of color as governor.” That said, Gibson was also careful not to paint himself as the “black candidate” for that office. He feared (unfortunately, justifiably) that tying himself too closely to that label could backfire on him. Instead, he spoke in more vague terms of “change” and “progress” and “a new generation of leadership”. In that way, he largely adapted the Kennedy brand of optimism and hope for the future.

Across the state, people’s eyes turned to Gibson. The crowded nature of the primary played to his advantage as well. By cultivating a loyal, dedicated following, Gibson outshone several of the less well-known candidates, and set himself up to challenge the “absentee candidate” - Florio. When the Democratic primary was held, on June 2nd, 1981, the number of candidates was thought to be the deciding factor.

With just 26.2% of the vote, Ken Gibson, Mayor of Newark, managed to eke out a win over Florio, who scored 25.4%, as well as all the other candidates. Though hardly a decisive victory, Gibson would be the Democratic nominee for governor of New Jersey in 1981. In a massive rally in his hometown, Gibson celebrated with his wife, Camille, and a crowd of devoted supporters.

In the general election, which was framed by the national media as a referendum on President Kennedy and his agenda (in particular, his economic and tax policies), Gibson would be going up against Thomas Kean, the former Speaker of the State Assembly and runner up for the GOP nomination in 1977.

Born on April 21st, 1935 in New York City to a long line of Dutch American and New Jersey politicians, Tom Kean seemed destined for greatness. His mother was Elizabeth Stuyvesant Howard and his father, Robert Kean, was a U.S. representative from 1939 until 1959. Kean's grandfather Hamilton Fish Kean and great-uncle John Kean both served as U.S. senators from New Jersey. His second great-uncle was Hamilton Fish, a U.S. senator, governor of New York, and U.S. secretary of state. Kean is also descended from William Livingston, who was a delegate to the Continental Congress, was the first governor of New Jersey, and is considered a founding father of the state.

Above: Tom Kean, the Republican candidate for Governor of New Jersey in 1981.

After attending a number of elite prep schools as a boy, Kean later attended Princeton University, where he performed “groundbreaking research” on the constitution of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and earned a BA in history. He would later earn an MA (also in history) from Columbia University and become a social studies teacher at St. Mark’s, the private Episcopalian boarding school he’d attended in his adolescence. He later got involved with Republican politics in New Jersey, serving as a volunteer and surrogate for numerous state level campaigns before eventually becoming a candidate for office himself.

A moderate, dyed-in-the-wool “Romney Republican” and proud member of the so-called “Eastern Establishment” of the GOP, Kean launched his campaign with pledges to foster job creation, to clean up toxic waste sites, to reduce crime, and to preserve what he called “home rule” for his state. This was largely seen as a jab at President Kennedy and the Democrats, who seemed to stand for increased federal involvement in the nation’s economic affairs. Kean won the endorsement of former President George Bush fairly early on in the race, which enabled him to capture the nomination.

As the general election campaign got underway over the summer, both candidates sought to contrast themselves on economic issues, down to the personal contrast between Kean as the scion of a wealthy, WASP-y political dynasty and Gibson as the upstart African-American symbol of upward mobility. Gibson continued his praise of President Kennedy’s economic program and worked to link Kean to Ronald Reagan and his “dangerous ideals of ‘slash and burn’ conservatism”. Meanwhile, Kean distanced himself from the conservative wing of the GOP, even going so far as to turn down Roger Stone’s offer to work for him as a “hitman”. Stone had proposed a series of highly controversial ads filled with dog whistles that would attack Gibson and his “element”, and question whether he was “ready to lead New Jersey”. Kean feared that these ads would lead to blowback and refused to work with Stone. Instead, Kean tried to pivot, attacking Gibson as “just another tax and spend liberal”, who would do nothing to clean up the state.

As the race wore on and it became clear that President Kennedy and his policies remained popular with the people of New Jersey, Kean even tried to paint himself as the perfect candidate for “bipartisanship”. In a series of two debates held at Monmouth College and later, before the New Jersey Chamber of Commerce, Gibson decried Kean’s economic policies as “voodoo economics” (echoing former President Bush) and claimed that a Kean governorship would lead to “financial devastation, possibly even bankruptcy”. Kean accused Gibson of speaking in hyperbole and of seeking to “continue Governor Byrne’s failed regulatory policies”. Both candidates postured as being “tough on crime”, a theme that would go national the following year.

In the final days of the race, the Republican National Committee (RNC) dumped hundreds of thousands of dollars to blanket the state in television and radio ads. One famous TV ad featured Kean playing bocce, in an evident attempt to appeal to ethnically Italian voters. To counter this, Vice President Lloyd Bentsen and Senator Bill Bradley appeared frequently with Gibson at his campaign rallies. President Kennedy even made a highly-publicized appearance a few days before Election Day, in which he endorsed Gibson and delivered a rousing speech on his behalf.

In the end, the race was close, a real nail-biter.

Early returns on election night showed a narrow lead for Gibson. But the race was widely reported on as being “too close to call”. Two networks - ABC and CBS - both declared Gibson the winner, only for the Kean campaign to demand a recount, as the margin appeared to be down to less than a thousand votes. A recount was held, but in the end, the results held. By a margin of only 507 votes, Kenneth Gibson was elected Governor of New Jersey.

The result, considered a major upset despite President Kennedy’s popularity, sent shockwaves through not just the state of New Jersey, not just the Northeast, but throughout the entire nation. In a decidedly purple swing state, an unabashedly liberal Democrat (and a man of color, no less) had just defeated a moderate, Romney Republican who came from one of the most storied and well-established political dynasties in the country.

The world, as they say, had turned upside down.

Above: Ken Gibson, in his newly won office as Governor of New Jersey, Jan. 1982.

…

Above: John Dalton (R - VA), Governor of Virginia prior to the 1981 election.

If New Jersey in 1981 was a northeastern swing state in need of reform, then Virginia was a leading state of the “new South”.