Chapter 41. The Rogues of Italy

1545-1553; Italy.

“I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble.”

— Augustus

Musical Accompaniment: Toccata Cromatica XII

Duke Filippo II Emanuele of Milan & Duke Ottavio of Parma, c. 1550s; AI Generated.

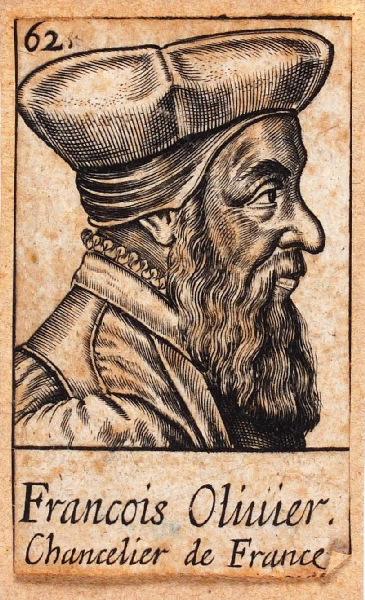

The death of King François in 1547 had profound effects on the Italian peninsula, which allowed for the Treaty of Compiègne to come into effect. The king’s youngest living son—Philippe Emmanuel, the Duke of Orléans, who would become more commonly known as

Filippo Emanuele, was finally enfeoffed with the Duchy of Milan and the Lordship of Genoa. As young Filippo was only twelve, it was decreed that his mother, Beatriz of Portugal, would serve as his regent until he came to age. Another concern was the erection of the Duchy of Parma in the territories surrounding Parma and Piacenza that Milan had once held. These were to be spun off into a second duchy, formed by the emperor, which was granted to the late French king’s eldest bastard son—Octave or

Ottavio as he too would become known. He too was still in his youth, at fourteen—and it was agreed that he too should have a regent in the person of

his mother, Anne Boullan—the Duchess of Plaisance and a long-standing rival to Beatriz of Portugal. These two women, who had long feuded in France, would soon export their problems into Italy.

Anne and Ottavio arrived at their new possessions first—Beatriz was detained by the forty-day mourning period carried out by the Dowager Queens of France. This head start allowed Anne to take hold of her son’s possessions and legitimize his territories in Italy—preventing their capture by Beatriz. Anne quickly took to the business of government and established her son’s court at the Palazzo del Governatore.

“It is a grim place,” Anne wrote in a letter to her brother back in France.

“Medieval and Romish, it has a beautiful edifice… but it does not compare to the châteaux of France.” One of her first decisions was to expend some £30,000 from her personal revenues to acquire a group of homes within Parma’s central square. She ordered them razed and soon began construction on what would become known as the

Palazzo di Santilario, which in time would become more commonly known as the

Palazzo Ducale.

Anne wanted to build a new palace for her son that would allow him to host a glorious court and enhance his power among the Italian princes. Anne worked chiefly with a small council—one of her primary advisors was

Andrea Casali, a renowned humanist; another was the Bishop of Parma—

Basilio Chiari. Anne did not dare rock the boat regarding Parma’s Catholic religious structures. While she continued to hear private Protestant sermons within her chapel, her son attended Catholic services hosted by Bishop Chiari.

“Were he merely the Duke of Plaisance in France, he would have been free to choose the dictates of his own consciousness,” Anne wrote in another letter to her brother.

“In Italy, the Catholic faith—and the Pope—reign supreme. If he is to reign here in this land, he must also be Catholic.” It wasn’t a thought that boded well for Anne, but she thought only of Ottavio.

“When he is grown, I can return to France,” Anne wrote in her diary.

“Only then will I be truly free to worship as I believe.” Anne still had many loyal servants—though some refused to continue in her service in Italy, she found new servants in Parma who became devoted to her. Anne also remained close to her siblings: Georges, the Duke of Valentinois, was not exactly welcomed at the more subdued court of François II and settled at Châlus with his wife Louise, where he dedicated himself to the management of his estates and the education of his two sons,

Alain (b. 1538) and

Jean (b. 1541) Marie, the Dame de La Bussière, and Anne’s elder sister agreed to accompany her to Parma—both as a companion and moral support.

“My sister has been more than kind to us,” Marie wrote in a letter to her husband.

“When her star was high in the sky, she did all she could for us. Now that her star has fallen, I feel compelled to offer her whatever support I can… I know that you shall be most busy with your archival work, and the children shall be in good hands… in hope to return in a year, perhaps two at the latest…”

The Coat of Arms of the Duke of Milan—

Orléans quartered with those of Milan, used by the Visconti.

Beatriz and Filippo did not reach Milan until the fall of 1547, but compared with Anne’s trepidation, Beatriz was overjoyed.

“Even the air here is fresher and lighter compared to that which I have breathed day in and day out,” Beatriz would write in a joyous letter to her brother in Portugal.

“Twenty years of heartache and trouble faded when I crossed the frontier.” Beatriz and Filippo first took up residence in Pavia at Visconti Castle, with the queen dowager issuing strict instructions that both

Palazzo Ducale in Milan should be prepared for her son’s inhabitance, alongside the

Castello Sforzesca. It did not take long for Beatriz to earn a reputation as a taskmaster among the Milanese. Many of them fondly referred to the queen dowager as

Madama Vedova—Madam Widow.

“Queen Dowager Beatriz left France loaded down with whatever she could take with her,” one historian wrote.

“Furniture, tapestries—even books, glassware, and candles—all were taken so that they could decorate the spartan Milanese palazzo and castles, some of which had not been inhabited in decades. In one instance, Beatriz even carted away her featherbed from Fontainebleau. When Queen Isabelle took possession of the queen dowager’s chambers, she could not help but remark: ‘Perhaps an inventory would be easier if we counted that which the queen dowager has not taken.’ While some items were in the queen’s right to take, others, perhaps, were not—from the royal library, she claimed tomes that had previously been a part of the Visconti library… half had been removed from Pavia to France in 1498; she succeeded in claiming about a third of the books to be returned.” Like Anne, Beatriz was desperate to make the Milanese residences comfortable for herself and her son. Unlike Anne, Beatriz intended to remain in Italy until she took her last dying breath. Beatriz used her jointure, valued at some £35,000 per annum, liberally—she used funds shortly after her arrival to purchase land near the ducal park in Milan to build her own private residence, the

Padiglione del Porto.

Beatriz had always been denied an official political position throughout her marriage to King François. Despite this, she proved to be a quick study. The first move was to weaken French influence within the Senate of Milan—she named

Ippolito d’Este, the Archbishop of Milan, her primary minister. Even her household was purged of French influence, with Beatriz naming Ricciarda Malaspina, the Marquise of Massa, as her primary lady-in-waiting. Beatriz’s working relationship with the archbishop proved helpful. It allowed her to build relationships with Italy’s native princes—such as Ippolito’s brother, Ercole II—the Duke of Ferrara and Modena. Ercole II had been wed to the daughter of the late Claude of Lorraine, Maria of Lorraine, who had given him two sons,

Alfonso (b. 1534) and

Claudio (b. 1545), and a daughter

Maria Antoinetta (b. 1543). It had not been a happy marriage, and Ercole shed no tears upon her death. Ercole was one of the first princes invited to Milan by Beatriz—with some whispering that perhaps she had an ulterior motive.

“She has moved through the seasons—spring, summer, and fall, with tragedy at every turn,” one Italian poet allegedly wrote.

“In the winter of life, a new love springs forth to revive.” For the first time in her life, Beatriz discovered that men were not all lecherous creatures.

“I discovered that men, even handsome ones—could be kind… and dare I say, loving?” She wrote in a letter to the Marquise of Massa. Ercole lavished attention upon the queen dowager—lavishing her with gifts and trinkets while spending as much time in Milan with her as he possibly could. By 1548, Ercole had swept Beatriz entirely off her feet. They wed secretly at Santa Maria del Carmine; by late 1549, the secret was out when Beatriz discovered she was pregnant. The marriage was publicly solemnized at the ducal chapel by the Archbishop of Milan, and Beatriz soon adopted the style of

Duchess of Ferrara, Modena, and Reggio—along with inviting Ercole II to share in the authority of the regency of Milan

. Beatriz would give birth to a daughter named

Isabella in the spring of 1550. At forty-six, Beatriz had not expected to remarry, let alone have another child—but she was beyond overjoyed.

“Better a duchess in happiness and health,” Beatriz reportedly told one of her ladies.

“Then a queen in tragedy and misery.” Beatriz’s ambition had not tempered—she still wished for her son to shine brighter than all the other Italian princes. But for the first time, Beatriz was

content with her own life.

With Filippo Emanuele nearing his fourteenth birthday, Beatriz knew it would soon be time for him to take a wife—either a Spanish princess or one of the emperor’s daughters. She settled upon a Spanish match for her son, accepting through the

Treaty of Chiavari in 1549 that formally betrothed her son to the Spanish Infanta

Leonor (b. 1540), who was Beatriz’s niece through her late sister Isabella. Though Leonor was still young, it was arranged that they would be wed shortly following the infanta’s twelfth birthday in 1552, allowing her to spend the final years of her education in Milan. Beatriz sent tutors to Spain to educate Leonor in Italian and etiquette. They even began to exchange letters—with Beatriz wishing to have a better relationship with Leonor than she had ever had in France with her other daughter-in-law, Isabelle.

“We are daily waiting for the years to pass so that you might finally be able to join us,” Beatriz wrote in a honied letter to Leonor, dated in 1550.

“My son treasures the miniature that your father sent, and already he has begun decorating your chambers, a most spacious suite of rooms that will adjoin his own…” Under Beatriz’s aegis, Milan became a glittering court—a

Maestro di Stalla managed the stables, while the

Cacciatore handled the court’s hunting excursions. The

Maggiordomo di Palazzo managed the ducal household, while the duke’s chamber was managed by the

Ciambello. Beatriz had her own separate household.

“The birth of Milan’s court etiquette came through Duke Filippo’s installation as Duke of Milan. The household was reconstituted from scratch—mostly along French lines, as no ducal household had existed for nearly fifty years.” Filippo Emanuele formally attained his majority at the age of eighteen in 1553. Though Beatriz was allowed to retire from the regency, she was immediately appointed to the

Consiglio Ducale, which served Milan’s privy council. Duke Filippo also invited his stepfather, the Duke of Ferrara to advise him on matters of state.

Milan Embraces the Duke of Milan—Allegorical Fresco of Milan's Palazzo Ducale, c. 1570; AI Generated.

If Milan represented Italy’s jewel, Parma represented a more provincial backwater. Though the Duchess of Plaisance did what she could to raise the standards in Parma, she understood her son occupied a small sovereign territory. Parma was less a city than a town, with some 20,000 souls—while the duchy possessed perhaps some 250,000 souls.

“We have no true treasury to speak of,” Anne wrote piteously to her brother.

“The annual revenues are piteous—some £20,000 per annum, with which I am expected to fund the court, carry out renovations, repairs, and new constructions, and pay our army. Our army is a mere 4000 men… perhaps five hundred of those are fit for fighting service as members of the ducal guard, former men of the Armée d’Italie… their costs alone consume over half the revenues…” Anne was forced to use her revenues from France to cover the numerous shortfalls.

“It must be something we acquaint ourselves with,” Anne reportedly quipped to one of her ladies-in-waiting.

“When I am but dust and gone, my son shall be forced to do the same.” While Beatriz could rest easy in Milan, Anne’s time in Parma was one of worry and anguish.

“While Beatriz had left the misery of France for brighter pastures,” one historian wrote in the opening lines of

Anne & Beatriz: The Rogues of Italy.

“Anne’s experience was the opposite—losing her protector and benefactor, she left the protection of France for the unknown of Italy, where for the first time she had not won the first prize. Parma’s sovereignty was an important win, but its territory and wealth were a pittance compared to Milan and Genoa—who had the support of the Habsburgs behind them. Alone in an alien land that did not even recognize her faith. For perhaps the first time in her life, the cossetted maîtresse of François I faced her first ever genuine challenge.”

South of Milan was the Kingdom of Naples—still secure under the rule of the House of Lorraine. By 1549, Louis IV—better known as

Luigi IV, had sat on the Neapolitan throne for nearly twenty years. He had wed a Princess of France, Louise, and their match proved fecund, with two daughters,

Francesca (b. 1536) and

Claudia (b. 1542), and two sons,

Renato (b. 1537) and

Antonio (b. 1541). Two children had died young—

Giovanna in 1538, shortly after birth, and

Giovanni, who died in 1545 at the age of four.

“Both the king and queen were in misery following the young prince’s death,” one lady-in-waiting to Louise wrote.

“They wept and prayed together, but to no avail—while the king was made of sterner stuff and able to move forward, the queen could not. Delicate and shy, she was not meant for the public life of a consort… she withdrew into her chambers following the young prince’s death, complaining of maladies that struck at her head and her back like daggers cutting through the flesh. His Majesty did all he could for her, even staying at her side for her last moments. Three months after the death of the young prince, our queen perished as well.” It was said that Luigi was inconsolable at the death of his wife, whom he had been fond of. Louise was given an opulent funeral and was laid to rest in the

Basilica of Santa Chiara. Louise was the first queen to be buried within the basilica since Giovanna of Naples in 1382—Luigi used the funeral to demonstrate his claims to Naples through the Angevin line. Shortly after, the king hired Pirro Ligorio as a royal architect—Luigi desired for Ligorio to not only construct a tomb for the late queen but also paint new frescoes within the basilica and update its Gothic interior. Luigi would spend some 250,000 ducats renovating Santa Chiara, which he intended to be the burial place of his dynasty. Though the Neapolitan line was secure, some within the king’s council pressed him to consider the possibility of remarriage.

“You are yet young, sire,” Scipione Farinacci, the king’s chief councilor, cautioned.

“More than that, the royal princes and princesses are still young—Signora Francesca is nine, and Signor Renato is eight; the youngest, Signor Antonio and Signora Claudia are six and three. You are a most august parent, but the kingdom’s demands also weigh upon you… what they shall need is a mother’s love and affection.” The king at first resisted these calls to remarry, reportedly chastising the council:

“Her Majesty’s body is not yet cold, yet you already seek to replace her. Remember, sirs, the good that she did—and how well she treated all of you.”

By 1547, the king relented and agreed to remarry—but he did not give the council a chance to find him a wife; instead, he announced before them that he did intend to wed again—and that his future wife and queen would be Isabella of Savoy—a maid of honor within Queen Louise’s former household. Isabella, born in 1529, was the daughter of

Philippe of Savoy, better known as the

Duke of Nemours, who had died shortly before her birth. Isabella was better known because of her mother,

Bona Sforza—the

Duchess of Bari and

Princess of Rossano. Isabella’s parents had not wed for love—Bona wed Philippe at the late age of thirty-two to protect her lands and interests during the French occupation of Naples, though he had been proposed as a husband in her youth. Wed in 1526, Philippe had left Bona pregnant in 1528 and died five months later. Four months later, in early 1529, Isabella was born. Luigi IV had become king, and Bona felt secure as the widow of a prince aligned with France. Though she often attended court, she preferred to reside in her domains. Still, Isabella had been sent to court at a young age, and though the pretty girl had many suitors, her mother always hoped for a more extraordinary match. What was more extraordinary than the King of Naples?

Isabella of Savoy, c. 1547; AI Generated.

“Bona, the Duchess of Bari, had once been a jewel of the Sforza dynasty,” one historian would write in their biography about Bona, titled

Jewel of the Sforza.

“She was considered as a consort for her cousin Massimiliano—a plan that collapsed following the French invasion of Italy in 1515 that deposed the Sforza in Milan for good. Other proposals came and failed—Guiliano de Medici, Ferdinand, the Prince of Asturias, and even Philippe of Savoy and Lorenzo de Medici, the Duke of Urbino… all these matches failed, and Bona languished in Bari, where she succeeded her mother in 1524 as Duchess of Bari. She quickly fell into conflict with the Spanish; the Viceroy of Naples, Hugo of Moncada, attempted to bully Bona into willing her territories into Spain, given her lack of an heir. He also solicited loans for his government in Naples that would eventually reach the sum of some 200,000 ducats. There also remained unsolved issues regarding the inheritance of her great-aunt, Joanna of Aragon, the late Queen of Naples: she had willed a significant portion of her fortune to Bona’s mother, but part was held by Charles V as King of Spain. When the French invaded Naples, she quickly threw her lot with them and was favorably rewarded; when Luigi IV became king, one of his first acts was to allow Bona to claim the whole of her great aunt’s inheritance that existed within Naples, which made her even wealthier. Still, she could not but hope that her daughter’s future might be more brilliant than her own—and that her daughter might marry a king.”

It surprised very few that Bona Sforza’s daughter had triumphed as the prime candidate for the widowed king’s hand.

“All know that the Duchess of Bari is perhaps one of the wealthiest women in the kingdom,” one courtier wrote in a gossipy letter.

“If her daughter has truly secured the king’s affections, then the duchess shall give anything to see that her daughter becomes queen.” This proved prescient, as Bona offered a massive dowry of 350,000 ducats that dwarfed even what the king had received from France. The marriage contract was signed at Aversa in June 1547: the main stipulations centered around Bona Sforza’s landed domains. Luigi agreed that Isabella should have unrestricted inheritance of both Bari and Rossano when Bona died and that the domains would be administered by Isabella outside of the royal demesne for her life. In terms of the succession to Bona’s lands, the marriage agreement recognized that Isabella would pass the duchy either to her eldest son (or barring sons) to her eldest daughter—with the marriage of the future Duchess of Bari to be decided by the (future) King of Naples. If Isabella had no issue with the king, it was agreed that Isabella would recognize Renato, the king’s eldest son and heir, as her successor. Luigi and Isabella married several days later in a subdued ceremony at the Chapel of Santa Maria a Sicola in Naples.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes by Raphael as part of the Raphael Cartoons; c. 1515-16.

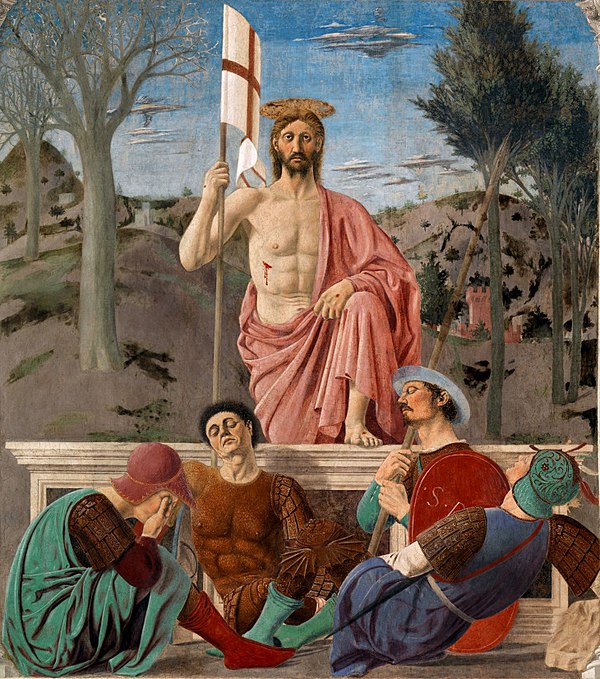

In Rome, all concerned the newly elected Pope Adrian VI—formally Reginald Pole—who had triumphed in the 1549-50 Conclave. Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury and now mother of the pope, wrote a letter to Queen Mary when she discovered the news.

“God is most truly gracious… I could have never imagined that one of my sons might have risen to such heights, let alone the glories of serving as our Holy Father and guiding our church. I am truly most content, madame.” The countess passed away a few months into Pope Adrian’s new reign in August 1550—several weeks before her seventy-sixth birthday. The election of Adrian VI represented a significant victory for the

Spirituali, or evangelists—those who believed that their church and faith needed reform—primarily through spiritual renewal and a more internal focus on faith through scripture and justification by faith. Adrian’s victory dealt a blow to the more conservative

Zelanti faction within the church, but it did not mean their destruction. Adrian entered his pontificate with some within the Roman Curia weary of his intentions, such as

Cardinal Gian Pietro Carafa, who had sought to prevent Adrian VI’s election and failed. Carafa’s hatred and rivalry with the new pope was so intense that Carafa even began to believe that Adrian VI was a wolf that masqueraded as a sheep.

“I believe firmly and fully with all my heart and soul,” Cardinal Carafa wrote to an associate.

“That we have erred, and this election shall be a blemish upon our Holy Church until the end times. Holy Father, he may be, but he cannot be trusted. I know within my heart and soul that the man is a fraud and a Lutheran… he shall destroy us all if given the chance, and I refuse to let him do so.”

Adrian VI did not concern himself much with Carafa—in Adrian’s eyes, the man was merely a sore loser. One of Adrian’s first acts as pope was to reorganize the curia. He nominated as

Cardinal-Nephew his nephew Arthur—eldest son of his younger brother, Geoffrey. Arthur was named Cardinal-Deacon with the titular church of

Santa Maria in Cosmedin, which Adrian had previously held. Adrian VI took steps to delineate his nephew’s role within his papacy, writing to Arthur:

“Know that I give you this honor for the glory of our church and not of our house. I shall lean upon you for your assistance; know that I shall reward you well for this but in line with your accomplishments. Do not think you shall reap riches merely upon your name and title alone.” Adrian VI immediately sought to make changes to the curia.

Giovanni Morone was named Vice Chancellor, while

Francesco Pisani was named Camerlengo.

Giovanni Domenico de Cupis was named the first

Cardinal-Secretary of State. The pope tasked Cardinal Cupis to serve as a tutor and instructor to his nephew.

“Pope Adrian VI was deliberate in his choices—though he had spent nearly twenty years in Rome, he understood the Romans would see him as a foreigner and Englishman first and foremost.” one biographer of Adrian VI wrote.

“He desired to surround himself with those cardinals who would support his views but who had established relationships within the church already.” Adrian VI’s first formal consistory was held in the Summer of 1550—he nominated not only his nephew Arthur Pole but

Edigio Foscarari,

Pietro Lippomano, Isidoro Chiari, and

Girolamo Seripano—all men that held views within the bounds of the S

pirituali. Another appointee was

Cuthbert Tunstall, Archbishop of Canterbury—who was recognized as Crown-Cardinal of England and England’s first who was not an Italian.

Robert de Croÿ, the Bishop of Cambrai, was also appointed alongside

Jean Suau of France.

Adrian VI placed very great importance upon the Council of Bologna. Though the council had been opened in the year previously by Gelasius III, his death shortly after its opening had robbed the church of needed initiative. The issue of Protestant attendance also remained up in the air. Though Charles V demanded that the German Protestants send a delegation to Bologna, many remained intransigent about attending a council in the heart of the Papal States. These matters were compounded in the fall of 1550 when an outbreak of the plague occurred in Bologna—leading Adrian to prorogue the council before it even truly opened to begin any deliberations. Adrian, intent on reopening the council before the end of 1551, decided that the council needed to be moved. Adrian received numerous suggestions and offers—some suggested moving the council into Germany; Charles V offered up Besançon alongside Konstanz as a possible location. François II incensed at the idea, threatened to host a national council in France and to embargo the export of gold to Rome if the council was moved to Germany.

“A council in Germany would be dominated by schismatics and heretics,” François II wrote in an adamant letter to Adrian VI.

“Remember well that France is the eldest daughter of the church; should you sacrifice our affection, you risk sacrificing our obedience as well.” François offered up the city of Arles and suggested that the pope consider moving the council to Avignon—ideas that also met the emperor’s rejection.

“My son-in-law holds a knife at your throat and expects you to bow to his authority,” Charles V wrote to the pope.

“You cannot hold the council in Arles or even Avignon—it will stink of French influence that damned the last council. The Protestants will not attend such a council. I cannot guarantee that German prelates would either… and if the Germans do not attend, you may be assured that the English and Spanish will also think otherwise, dooming your good intentions to another shuttered council.” The Venetians offered up Padua, but Adrian VI dismissed the offer with thanks. He remembered well the failures that had plagued the previous Council of Bologna—and the move to Verona did not fix them. In the end, Adrian secured an agreement with

Lucerne to move the council there.

“It cannot displease anyone,” Adrian VI wrote in a letter to Cardinal Morone.

“Lucerne lays outside the dominions of the emperor and King of France; it is not in Italy, nor in Germany… more than that, the city and patricians have agreed to assist in financing the council, which will help matters greatly.” With plans to reopen the council, now known as the

Council of Lucerne, Adrian appointed three new legates to attend:

Niccolò Ardinghelli,

Ercole Gonzaga, and

Gasparo Contarini[1]. All three men were chosen not because of their wide breadth of knowledge and credentials but because of their firm belief that the Catholic Church needed reform—views that aligned with the pope’s own.

Religious issues would largely dominate and overshadow Adrian’s pontificate. Despite this, Adrian VI attempted to implement fiscal and political reforms to the best of his ability. Adrian spent vast sums to expand Ancona’s port, which had been declared a free port in 1532. He also allowed Jews to continue to settle in Ancona as well as Rome—though the yellow badge was still strictly enforced. Adrian also sought to provide relief to the

Conversanos and

Marranos, who daily begged the Roman Curia for relief—paying vast sums for the privilege to beg like dogs. While Adrian VI dared not meddle in the affairs of Spain or Portugal, he made the gift of the islands of Ponza and Ventotene (uninhabited since medieval times) to the Iberian Jewish community residing in Rome for an annual rent of 6000 scudi.

“Settle these islands and make them yours,” Adrian exhorted to the Jewish envoys.

“They shall suit your needs perfectly—should you agree to live quietly, prosper, fortify them, and pay what you shall owe us each year, they are yours.” Adrian ensured that the Jews within the dominions of the church fell under his protection—and that they were solely under his own authority. Adrian also sought to balance out papal finances—he instituted measures of economy within the Papal Household while slightly increasing the nominal fees owed for dispensations and also to file suits within the Apostolic Camera.

“While Pope Adrian VI’s fiscal policy was not without its issues,” one historian of Adrian’s policy wrote.

“It made him the first pope of his era that attempted to deal with Rome’s unsettled financial situation. While Adrian VI might have simply accumulated more debt through the luoghi di monte like his predecessors (which he still did, to an extent), he truly attempted to bring about a change.” New direct taxes were also established to maintain the papal galleys and papal armies, while the

gabella delle carne was introduced in 1552 as a direct tax on meat. Compared with previous Popes, Adrian attempted to work with the Roman Curia as best he could. While the curia was in no way returned to its former status as the Senate of the Roman Church; it enjoyed more input and influence over Papal policies than it had in previous pontificates—even if it was those aligned with Adrian’s VI’s policies who received the most benefit from this change.

Allegory of Redemption, Lucas Cranach the Younger; c. 1557.

As 1551 opened in Parma, Anne’s primary concern was to search for a wife for her son—who had recently attained his majority.

“Though the young Duke of Parma possessed the blood of the House of Valois—it was from the wrong side of the blanket,” one historian would write.

“Few Italian princes had the desired to attach themselves to the late King of France’s bastard—especially when the new interests of François II heralded the possibility of Italy shaking off the Italian yoke.” With the Duke of Ferrara’s marriage to Beatriz, any union with the House of Este was impossible. Not even the parvenus of Italy, the Medici expressed interest in such a union.

“My wife is the bastard of an emperor,” Duke Lorenzo III uttered.

“I shall not wed one of my daughters to the bastard of a king.” Eventually, Anne arranged for Ottavio to marry a daughter of the Lord of Monaco,

Francesca Grimaldi (b. 1536), through the

Treaty of Piacenza signed in June 1551. Ottavio would wed his Monégasque bride in the spring of 1552 in grand style at the Palazzo del Governatore, which the court currently occupied.

“The Duchess of Plaisance wished for her son’s wedding to be an opulent affair,” the

Rogues of Italy continued.

“She spared no expense—some £5000 was raised through an extraordinary tax in Parma (to great discontent and grumbling), while she would expend another £25,000 of her own funds, which she ordered sent to a Florentine bank from France, fearing the Genoese might not be as helpful. Though the wedding was grand, Beatriz sought to outdo her rival everywhere… it was rumored that some £60,000 alone was spent on the Duke of Milan’s wedding to his young Spanish bride held in the same year, which included a religious ceremony at the Cathedral of Milan and massive feasts and celebrations at the Palazzo Ducale which lasted for several days and included many dignitaries, with many Italian ambassadors attending on behalf of their masters and offering felicitations to the newly married couple. In contrast, the wedding of the Duke of Parma was grand, if not subdued—attended primarily by the gentry and nobility of the duchy.” Though the Duke of Parma was now wed and had assumed the government over his duchy, Anne remained in Parma as a valuable source of support, despite her desire to return to France.

“So long as he wishes for me to be here, so I shall stay,” Anne told her sister Marie.

“In truth, I cannot leave so long as the Portuguese harpy breathes… were I to retire to France tomorrow, the next day, my son would be dead. The late king fought for him to receive this duchy… I will not allow it to be lost so long as I am alive…”

The early 1550s represented a flourishing period for the Italian peninsula.

“Little more than serviles, we have been trampled and crumpled under the boot of the French,” An Italian pamphleteer, Niccolò Franco, wrote in

Il Secondo Raptio (The Second Rape), a pamphlet published in 1552 that attacked French influence in Italy.

“Robbed, beaten, corrupted: we are once more the Sabines at the mercy of a mighty Rome, without its true luster.” Such political tracts attacking the French became increasingly common at the start of the decade, primarily coming out of Milan and other Italian cities, such as Ferrara, Florence, and even Rome. Niccolò Franco, once in the service of the Duke of Mantua, was invited to enter Milanese service. Beatriz provided Franco with a pension of 300 scudi and named him

cameriere di camera within her son’s household. There was a revival in Italian culture, and many Italian artists and musicians saw themselves as patriots—viewing their culture under attack by the dominion of France.

“The French are leeches and always have been,” one Italian musician reportedly wrote in a letter.

“The refinement and elegance for which they are known for come from us… when they descended upon us in 1494, they were no better than barbarians. They have claimed our art, music, and heritage as their own…” France’s position in Italy following the death of François I had greatly shifted; François II saw the matter of Italy as finished and following the cessation of Milan and Genoa to Filippo Emmanuele and that of Parma to Ottavio, he ordered the French administration in Italy scaled down.

“Italy has been conquered,” François II wrote in his private diary.

“It is chained to us through our princes and men, and it shall always be. Italy was my father’s dream; It is finished. I dream instead of Artois and Franche-Comté, dominions that by right belong to my wife (and myself) but which have been denied to us for nearly twenty years. I strive for France’s greatness before all things.”

Allegory of Wisdom and Strength, Paolo Veronese; c. 1555.

In 1547, François II signed the

Treaty of Novara with the Duke of Savoy—returning to Carlo III the dominions he had lost nearly ten years before—though Carlo was forced to recognize French influence over Saluzzo, held by Michele II, son of the late Marquis Francesco Ludovico. A year later, in 1549, François II abolished the French governorships in Milan and Genoa, ending the parallel governments that had hereto existed in both regions since 1547. François II ordered the recall of French administrators from both areas, allowing the Milanese regency to appoint their own officials for the first time. These changes were soon followed by reductions in the 1550s of the

Armée d’Italie. “French finances were in poor shape in the early reign of François II—owing to the profligacy of his father,” one historian wrote.

“When François Ier died, French annual revenues stood at nearly seven million livres—but they were swallowed almost completely by the late king’s debts: he owed nearly seven million alone to financiers in Lyons; some three million was owed to the city of Paris through the Bureau de Ville, and debts accumulated from the wars of 1536 and 1542 totaled almost four million.”

While François could restructure and reschedule some of his father’s debts in 1550, his financial situation remained dire. Though he introduced financial innovations to the

Maison du Roi, one of the king’s councilors, Henri de Saint-Priest d’Épinac, attacked the bloated

Armée d’Italie as a source of the king’s financial woes.

“Men of France are garrisoned from Milan to Calabria, sire. It is the Armée d’Italie which is an anchor about your neck,” a letter from Saint-Priest to François II began—with the second part detailing alleged monthly expenses.

“Officer’s Wages—£63,000. Soldier’s Wages—£50,000. Supplies—£38,000. Horses—£20,000. Gunpowder—£18,000. This great army costs Your Majesty some two million livres per annum. To restore the treasury, expenses in Italy must be lessened considerably.” François II paid heed to Saint-Priest’s suggestions: in 1550, garrisons in Naples were ordered to be drastically reduced. In 1551, François planned with Adrian VI to restore the port of Civitavecchia to the pope. French garrisons in central Italy were also drastically curtailed—those at Bologna, Ferrara, and Florence were dissolved completely, leaving a force of some 3000 men that would be based instead in Parma—retained only at the behest of the Duchess of Plaisance. By 1553, François II ordered the headquarters of the

Armée d’Italie shifted to Alessandria, granted to them by the Duke of Milan. By 1553, the army in Lombardy now numbered some 11,000 men, its posture shifted from conquest to defense.

“The Armée d’Italie should function as an instrument of security, not of conquest,” François II wrote again in his diaries.

“It must be augmented by the troops of our Italian vassals and friends—Italians should bleed for Italy, not Frenchmen.” It indeed represented a kind thought—though perhaps not a realistic one when the Duke of Milan, despite being a French prince, looked instead to his Habsburg cousins for succor in place of his French brother. It was not a unique thought—and by 1553, many others in Italy felt the same.