Brutal Youth

1611

Completing a process that began in 1608 when the Emperor Rudolf II surrendered control over Austria, Bohemia and Hungary to his brother Matthias because of the dissatisfaction of the nobles of those countries with his rule, the Emperor allows his brother to become King of Bohemia, leaving Rudolf’s only major role that of Emperor itself.

Almost simultaneously in Wittenberg, in his last major act as the Elector of Saxony, Alexander institutes a new succession law that to some extent conflicts with the constitution of the Holy Roman Empire—it permits daughters to inherit the Electoral dignity if there are no living sons or male issue of sons of the Elector. The decree is obviously a tribute by the dying Alexander to his favorite child, the Electress Eleonore of Brandenburg.

Soon afterwards Eleonore scandalizes the court by petitioning the Lutheran Church for the annulment of her marriage to the Elector of Brandenburg on the grounds of his conversion to Calvinism. The Elector John Sigismund had offered to allow Eleonore the free practice of her Lutheranism, and conventionally wives and children of converting rulers followed the ruler in adopting a new faith, thus making Eleonore’s decision seem to many unnecessary and extreme. Alexander himself worried aloud if it was wise to humiliate the Elector of Brandenburg so, but nonetheless would not attempt to veto the Church’s decision with respect to the annulment. The Lutheran Church itself, anxious to defend against the inroads being made by other sects, and seeing in the Electress Eleonore a potential champion for its interests, responds with a statement praising her constancy in her faith and granting in full the dispensation she sought. When she returned to Wittenberg from Berlin in 1610 she left behind seven children at the court of the Elector of Brandenburg.

Another conversion further complicates both Wettin family politics and foreign policy. Long under the influence of Rudolf II, and having participated in many of the Emperor’s campaigns against the Ottoman Turks, Adam Wenceslaus the Duke of Teschen converts to Catholicism. Unlike Eleonore, his wife Sybille—also a daughter of the Elector—refuses to dissolve the marriage and follows him into the Catholic faith.

The Protestant princes of Germany continue to search for some compromise capable of officially ending the War of the Julich Succession, but the death of Duke John in securing the inheritance for the Wettins has made it unthinkable for Saxony to surrender any of the lands. Functionally, this makes a peace treaty impossible.

As if to complicate matters further, Hafen bursts into unexpected revolt, as Erik the Margrave of Hafen and Governor-General of the Colony barely manages to escape with his life. Huguenot, Anabaptist, and Hussite ministers had been instilling anger against the importation of slaves into the colony. To some extent, this sentiment is the result of political and economic animosity between the numerical majority of Hafenites—skilled laborers and small farmers who were religious refugees from Europe—and the owners of most of the land, who were Saxon or English planters growing sugar and tobacco. Specific points of contention included the imposition of Lutheranism as the official religion in a colony where only a fifth of the population were Lutherans, favoritism for Saxon planters in the distribution of lands in the interior, and restraints on the immigration of more Huguenots, Anabaptists, Hussites and German Calvinists.

Matters in Hafen reach a crisis when the rebels, under Paul Marais, begin emancipating the Irish slaves. In the first six months in which the rebels have power, 30,000 Irish are freed. The Irish in turn begin fleeing west to the country across the Kogalu River called Ausreisserland.

Disruption in the revenues from Hafen and the breakdown in the Atlantic trade cause severe problems to the Saxon fiscal situation. Meeting in Wittenberg, the triumvirate meets to determine a course of action: Eleonore and Albert convince William, the youngest son of the Elector Alexander, that he must be the one to break the rebels in North America because Albert must be on hand to fight in case hostilities with the Emperor start again. William thus begins preparing to lead an army to Hafen.

The one area in which the Wettins’ foreign policy interests seem to be on the mend is the Netherlands, where Frederick Augustus reaches an agreement for ten years’ peace with the Spanish, who are compelled to recognize a truce line that grants the Dutch Brabant and northern Flanders.

Sophia of Sweden, widow of Ernest Brandon, aunt by marriage of the current King of England, cousin in law of the Elector Alexander and for all intents and purposes the foster mother of his children, dies, throwing the Saxon court more deeply into mourning. Albert has a son, which he names John after his deceased brother.

1612

Arriving in Hafen, William successfully puts down the revolt and restores order following a brief siege of Festung Erlosung, though he finds the economy of the colony wrecked by the flight of the slaves and the absence of available labor. Fearful because of the restless of the colony’s Huguenot majority, William puts Paul Marais and other leaders of the revolt to death.

The Elector Alexander dies. He is succeeded by his grandson, the Elector Christian, and his will officially approves the appointment of the triumvirate to govern until he reaches majority. However, with William in Hafen, the triumvirate now officially includes the Electress Eleonore, Albert, who is given the title Duke of Saxony, and the Elector’s counselor Hugo Grotius. Christian is invested with the Electoral dignity in Wittenberg in a ceremony unattended by the Emperor, any leading Catholic prince or official of the empire, or the Elector of Brandenburg. Though there is no small amount of pageantry to celebrate the first elevation of a new elector in 52 years, it is hard to avoid the sparse turnout of dignitaries and the problems it signifies for the Wettins in German politics.

Elector Christian I the Impetuous 1612-1631

The fourteen-year old Elector is expected to rule with the aid of the regent triumvirs until he reaches the age of twenty, giving him the opportunity to pursue education in the special course of studies crafted by Luther, Melanchthon, and Duke Julius of Brunswick-Luneburg for future Saxon electors at the University of Wittenberg, as well as extensive training at the special military academy founded by his father at Weimar.

Eleonore, the Electress of Brandenburg and the informal leader of the triumvirate, founds a university for women in Dresden in the former Wettin residence at Pillnitz.

Eleonore also begins corresponding with Jindrich Matyas Thurn, a Protestant nobleman who had accumulated large holdings throughout the Habsburg domains during the recent wars with the Turks, including in Bohemia, where since 1605 he has been a member of that kingdom’s estates. She specifically begins inquiring about the possibility of electing a non-Habsburg king of Bohemia on the retirement or death of the current king, Matthias. Thurn assumes at first she means the young Christian.

However, Eleonore’s actual strategy is more complicated: she intends to install a Protestant as King of Bohemia other than Christian, in part to secure the assistance of Protestant German states that otherwise would have no reason to aid in the aggrandizement of Saxony. Then, she would use the four Protestant electors (of the Palatinate, Saxony, Brandenburg and Bohemia) to defeat the three ecclesiastical Catholic Electors (Mainz, Trier and Cologne) and install Christian as Holy Roman Emperor. At first, not even the young Elector himself knows of this plan. Nonetheless, Eleonore finds receptive replies from the Protestant nobles of Bohemia, not least because the region has looked enviously on the Saxon prosperity of the past fifty years and believes the personal union between Saxony and Bohemia that these nobles think she is proposing would be economically advantageous.

Eleonore’s conspiracy takes on a new immediacy when the Emperor Rudolf II dies in Prague. Nonetheless, because his designated successor Mathias has personally developed the reputation of being tolerant towards Protestants and had curbed Habsburg abuses in Hungary and Transylvania that were allowed to fester under Rudolf II’s rule, she understands that his election is not the time for Saxony to move against the Habsburgs. Thus, in a meeting of the Protestant Union princes before the election of the new Emperor the consensus decision is reached to support the election of Matthias as Emperor and thus defuse tensions between the Protestants and Catholic factions of the empire.

The famous artist Adriaen de Vries, late of the court of Emperor Rudolf, becomes the new court sculptor in Wittenberg.

Albert and Elisabeth of Courland have a second son, whom he names Frederick.

1613

The first meetings of the Estates-General are held in Ridinger’s baroque schloss in Elster, the opulence of which over-awes visiting German princes. In the most delicate business before the Estates-General, Albert and Eleonore must persuade the legislature to greatly expand itself and dilute the power of its membership by admitting representatives from the guilds, landowners, and other enterprises of the new lands acquired through the Julich inheritance. It is only with substantial cajoling from Eleonore that this is achieved.

In one of the first initiatives proposed by the Elector Christian, a Saxon voyage departs for India with the purpose of securing a permanent trading fort.

The Elector Christian also asks to lead a diplomatic mission to Istanbul to attempt to win concessions to Saxon overland trade through the Ottomans’ territories. The idea is deferred.

Spanish Jesuits working from St. Augustine locate the chief Irish settlements in Ausrisserland, and begin supplying the Irish with guns and other necessary supplies so as to defend themselves.

In recognition of Saxony’s support for his election and the cessation of all further hostilities in the Julich matter, the Emperor Matthias assents fully to the Saxon inheritance of Julich, Cleves, Burg, Mark and Ravensberg. This decision scandalizes the other leading Habsburg nobles, such as Maximilian of Austria, who had demanded a harsh policy against the Saxons.

Frederick Ernest, the deposed Duke of Saxony who had been implicated in the plot to overthrow the Elector Alexander, dies.

1614

Eleonore finds a partner for her Bohemian scheme in Christian, Prince of Anhalt-Bernburg, chief advisor to the young Elector of the Palatinate, Frederick V. She and Christian of Anhalt agree to try to put Frederick V forward as the next king of Bohemia. Moreover, as an inducement to Brandenburg to join them, they would partition the realms that historically pass with the Bohemian kingship, allowing Brandenburg to take Lusatia and Silesia. Then, Saxony, the enlarged Brandenburg and the personal union of Palatinate-Bohemia, all roughly equal in size, would use their combined majority to confer the title of Emperor upon the Elector Christian of Saxony.

A small Saxon fleet sets sail for India from Hamburg. The Elector Christian is cheered as he sends off the fleet from dockside. The Electress Eleonore (increasingly, the fact that her title relates to her marriage in Brandenburg and not to Saxony, and that she no longer narrowly speaking possesses that title since the marriage’s dissolution, is forgotten) uses the occasion to renegotiate the terms of Saxony’s commercial arrangement for the use of Hamburg’s ports, using as leverage the fact that Hamburg is now almost completely dependent on Saxon commerce and naval construction economically.

The young Elector travels to Scotland. There he marries James VI’s daughter the princess Elizabeth at Holyrood Palace. Although he strikes up a friendship with Scotland’s heir-apparent Prince Henry, the Elector Christian is unable to prevail upon James VI to reverse the enmities lingering from the War of the English Succession or to agree any of several trade and diplomatic schemes Christian had proposed.

In an important change in the pattern of Saxon colonial settlement, the Elector Christian charters an effort to settle the island of Granada, nominally under Spanish control but still unsettled. A group of Arminian Christians had asked for the charter but are rejected, and instead Christian gives the charter to his first-cousin once-removed by his great-uncle John Frederick, Alexander. Never again will it be Saxon practice to allow religious minorities to establish their own colonies. Immigration by these groups to Saxon colonies will be permitted, but without promises of special treatment for these groups, which recent events in Hafen indicate leads to unrest.

In Hafen, English traders bring the first shipment of African slaves.

Karl von Droste publishes his theories asserting that hot air is lighter than cold air, and that the reason why is not reducible to differences in the composition of the air in question but the behavior of the particles of air instead.

Margarethe von Kulmbach writes one of the rare commercially successful books of printed German poetry, sparking fresh interest in German as a literary language and winning for herself a stipend from the Elector.

1615

Eleonore and Christian of Anhalt seal the secret alliance between Saxony and the Palatinate by marrying the Elector Frederick V to the Elector Christian of Saxony’s sister Elizabeth. Eleonore next tries to enlist in the conspiracy her estranged husband, the Elector John Sigismund of Brandenburg. He is shocked by the recklessness of the plan and the likelihood that it will plunge Germany into full-scale war. Wanting no part of it even with Eleonore offering the inducements of Lusatia and Silesia, he grudgingly concedes his support for the election of a Protestant Emperor should Saxony and Palatinate succeed in all the preliminary steps of their plan.

The Saxons purchase land for a fortress and factory at Thiruvananthapuram, at the southern tip of India. From there they will export sandalwood and spices to Europe, and import Saxon manufactured goods, including weapony. Profitable almost immediately, it quickly begins to ease the problems arising from the Huguenot revolt in Hafen.

As part of the effort to incorporate the Julich inheritance into Saxony, the Lutheran Church formally establishes the system of gymnasia already present elsewhere in Germany. Also, the Elector founds the University of Cleves.

As a final boon to the new territories, the Electress Eleonore and the Elector Christian jointly propose building what is immediately known as “John’s Road” to honor the Elector’s father: it would connect Leipzig to Cleves, passing on its way through the territories the Duke John added to Saxony in the War of the Julich Succession. Some negotiations with other nobles will be necessary to build the road however, since it will partly pass through the territory of the Bishopric of Munster and Hesse.

Duke John’s widow Dorothea Maria of Anhalt begins an annual literary contest for the best written work of any kind in the German language.

The Electress Elizabeth of Scotland gives birth to her first child, a girl. She is named Anna, after her grandmother Anne of Denmark.

1616

As rumors spread of the decline of Emperor Matthias’s health, the Electress Eleonore rushes to ascertain the possibility of electing Frederick V, Elector of the Palatinate, King of Bohemia. Thurn and the other Bohemian nobles are enraged at her duplicity, since they had believed her intention had been to secure the throne of Bohemia for her nephew the Elector Christian of Saxony. Their response is simply and clearly that while they would consider breaking from the Habsburgs to join with Saxony, partake in its economic dynamism, and enjoy the protection of Germany’s most formidable state outside the Habsburg realm, they have no intention of undertaking all the risks of rejecting the Habsburgs for the ruler of the smaller, more obscure Palatinate.

Thus, Eleonore’s plan, already teetering on the edge since the Elector John Sigismund of Brandenburg’s rejection, seems now to be falling apart. Conferring with Christian of Anhalt at Fulda in Hesse, she asks if she would have the support of the Palatinate if the kingship of Bohemia went to Christian of Saxony. Christian of Anhalt’s response is that if the previous deal had been that one Elector would take the kingdom of Bohemia and the other the imperial throne, the principle should stand even if the roles were reversed, and so Frederick V should thus be the Protestant candidate for Emperor if Christian becomes king of Bohemia. Reluctantly, knowing that if she begrudges Christian of Anhalt the concession it would likely mean Saxony standing alone against the Habsburgs, Eleonore agrees to put Frederick V of the Palatinate and not Christian I of Saxony forward as the candidate for Emperor.

Finally, Eleonore then on her return to Wittenberg divulges her manipulations to the Elector Christian. He approves of everything but the final concession to the Palatinate, and makes plain that he feels the imperial throne is the birthright earned by his great-grandfather in his defeat of Charles V in the Schmalkaldic War.

Eleonore’s missteps have apparently all but doomed her plan, but for worse missteps on the part of the Habsburgs. For under the prodding of the Archduke Maximilian of Austria, the Emperor Matthias chooses to advance for the kingship of Bohemia the Archduke Ferdinand of Styria. Ferdinand, a devout Catholic and resolute leader of the Counter-Reformation in Styria, is precisely the candidate Eleonore most hoped the Habsburgs would put forward, since he is the most apt to magnify the fears of the Bohemian estates.

The Duke Albert begins overseeing franttic preparations for war.

In Transylvania, Stephen Bocskay dies. He is succeeded as Prince of Transylvania by Gabriel Bethlen, a close ally of Bocskay who supports maintaining Transylvania’s close ties with Protestant Europe in general and the Electorate of Saxony in particular.

The Elector Christian’s wife Elizabeth bears a second child, her first-born son, which she names Frederick Henry.

1617

The Elector Christian comes of age and the regency ends. He appoints Hugo Grotius his chancellor, angering the Lutheran Church since Grotius is an Arminian, as well as Frederick Augustus is Grotius is an adherent of a rival of the Stadtholder in the Netherlands. Despite Grotius’ appointment, it is plain the triumvirate is still in place and that in matters of statecraft the Electress Eleonore has preeminence over all but the Elector himself.

Letters make “the Bohemian Plan” in its final form known to key allies, including King Frederick I of England, Stadtholder Frederick Augustus of the Netherlands, and the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel. All give their assent to proceed. James VI of Scotland, despite his being the father-in-law of the Elector, is not notified or invited to participate because of his ambivalent relationship with the Electorate of Saxony.

Simultaneously, Eleonore orders pamphlets printed and distributed in Bohemia attacking Ferdinand of Styria as an enemy of the Protestant faith who would enforce absolute religious conformity.

As the Emperor Matthias officially announces he will step aside as King of Bohemia and nominates Ferdinand of Styria to succeed him, Eleonore hurriedly makes her final preparations, informing Thurn that Christian of Saxony will stand for election as King of Bohemia and that if he is elected he will accept the crown.

The final political blow is struck by Christian himself, who writes, publishes and distributes a public Letter to the Estates of the Kingdom of Bohemia. In it, he pledges himself to respect the freedoms of the Bohemian nobility, to maintain the principle of freedom of worship for all Christians within Bohemia, and to govern Bohemia for its own well-being rather than use its resources to fund projects elsewhere in his domains. This last point speaks to long term Bohemian complaints against the Habsburgs.

Despite Eleonore’s designs long having been an open secret in Protestant Europe, when the estates actually met in Prague and the Habsburgs discovered Christian of Saxony was standing as an alternative king, they were shocked beyond words. That shock turned to anger when the Bohemian estates voted overwhelmingly to elect Christian king over Ferdinand of Styria.

Almost immediately, a Saxon army of 12,000 under the leadership of Christian crosses the border into Bohemia to claim his crown. He is met on the way largely by enthusiastic crowds. In Prague, he is crowned the King of Bohemia, and Elizabeth of Scotland Queen.

The Habsburgs, in disarray, decamp from Prague. The Emperor Matthias appeals for a negotiated settlement, and his chief advisor Melchior Klesl proposes a settlement by which Bohemia would pass to the Saxon Elector, but lose its vote for Emperor to the Duke of Bavaria. This would correct the historical oddity by which Bohemia could be technically outside the Empire and the German nation and yet cast a vote for its ruler. Though totally unacceptable to Maximilian of Austria and Ferdinand of Styria, this option leads the Electress Eleonore—in an apparent double-cross of Frederick V of Palatinate and Christian of Anhalt—to send Klesl a favorable response.

Ultimately, the Habsburgs’ response to the crisis is to declare the election invalid, since the Emperor Rudolf II had by a prior decree (since rescinded) made the Bohemian throne hereditary. They thus claim Ferdinand is the King of Bohemia regardless of the actions by the estates.

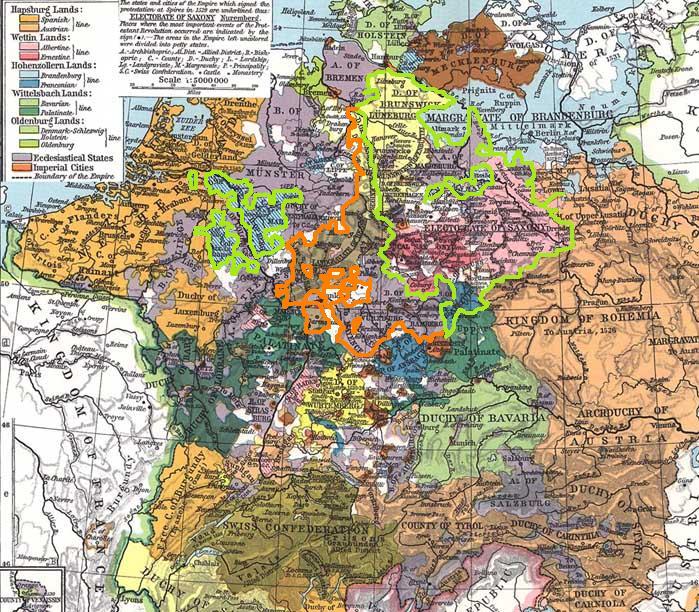

Essentially, with the exception of Brandenburg’s unsettling silence, the German principalities divide by religion, with the Protestant Princes and their Evangelical Union supporting the Wettin King of Bohemia, and the Catholic League championing the Habsburgs.

The Electress Elizabeth of Scotland gives birth to a third child and second son, Edward.

1618

Christian I enjoys a major triumph when the nobles of Silesia, Lusatia and Moravia, all historically bound to the Kingdom of Bohemia, announce they will follow Bohemia proper and accept his rule. Thus Christian becomes Duke of Silesia, Duke of Lusatia, and Margrave of Moravia. In each case he grants extensive liberties to the nobility and freedom of worship to virtually all Christians. In a special decree, he in fact establishes the positive right of Catholics to engage in religious processions free from interference, and moreover in Bohemia he decides some disputes over the construction of new Protestant churches in a fashion favorable to the Catholics, moves which disappoints many Calvinists and other radical Protestants in his territories, but which is obviously meant to make it more difficult for the Habsburgs to win support from their Catholic co-religionists.

Christian also visits the capitals of Moravia, Silesia, and Lusatia in a hurried tour to establish his bonds with each people, recruit troops for his army, and establish his rapport with the local nobility. In Brno, Christian meets Jan Amos Comenius, a holy man of the Protestant Unity of the Brethren, who almost immediately becomes a trusted advisor.

Saxony continues to mobilize, and by year’s end Christian possesses an army of 25,000 at Prague, his uncle Albert an army of approximately 20,000 at Wittenberg, with more forces at hand under Gabriel Bethlen in Transylvania and Frederick V in the Palatinate. Christian of Anhalt also brings the vehemently anti-Habsburg Duke Charles Emmanuel of Savoy into the alliance. In turn, Charles Emmanuel dispatches an army of mercenaries led by Ernest von Mansfeld to Bohemia.

On the Habsburgs’ side, there is a belated realization of how desperate matters are. The dying Emperor’s Matthias’s efforts to negotiate a compromise settlement, and the Electress Eleonore’s apparent encouragement of these efforts—whether out of a sincere wish to avoid bloodshed, or more likely, to play the Emperor against Ferdinand and Maximilian for as long as possible—prevent a coherent Habsburg response to the crisis.

Ferdinand and Maximilian, denied the resources of the rich lands of Bohemia, Silesia, Lusatia and Moravia, and lacking the support of the Emperor to move against Saxony, reach a series of agreements with friendly Catholic princes. Maximilian I of Bavaria agrees to lead the armies of the Catholic League to retake Bohemia, in exchange for the Upper Palatinate, the territories of the former Brandenburg-Kulmbach now subsumed within Saxony, and that part of Franconia under the control of the Hessian Landgraves. The Habsburg archdukes also send emissaries to Poland, where they promise Sigismund III Vasa Silesia and Lusatia in return for his assistance. Sigismund III Vasa’s response is not immediately forthcoming, chiefly because he is preoccupied by a war with Russia. A similar entreaty to King Henry IV of France falls on deaf ears, not least because Henry far prefers dealing with the Wettins than with his country’s ancestral enemies the Habsburgs. Finally, the Habsburgs entreat the Elector John Sigismund of Brandenburg to break with his longtime allies the Saxons, promising him the lands of Brunswick and Madgeburg in exchange merely for his permission to allow foreign armies to cross his territory to strike at Saxony, and his vote at the election of the next Emperor.

Elizabeth Kettler of Bohemia bears another son to the Duke Albert, Augustus.

1619

The Emperor Matthias dies. Almost immediately, the armies of the Catholic League under Tilly cross the frontier of Austria into Bohemia.

In a dazzling bit of misdirection, Gabriel Bethlen times the start of the Catholic invasion of Bohemia to lead his Transylvanian army into Royal Hungary, overwhelming the Habsburg defenses there and defeating a Habsburg army at Kecskemet. Technically, this is the first battle of the First General European War.

Then in Bohemia at Tabor, the armies of Count Tilly and the Elector Christian meet, with Tilly’s 17,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry matching the Elector’s 19,500 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. Though Tilly’s forces are better trained, the Elector has a greater number of his infantry wielding guns, and fields a great number of small artillery pieces that are easily movable around the battlefield. The result is a narrow Saxon victory. Tilly withdraws to Budejovice, a Catholic stronghold in southern Bohemia. The Saxon-Bohemian army does not immediately have the resources to pursue.

Habsburg emissaries had approached Sigismund III Vasa about the possibility of intervening in the war in exchange for grand territorial concessions in 1618, but Sigismund had not been able to reply immediately because of his war with Russia, the Dymitriads. However, in December 1618 Sigismund III Vasa signed the Truce of Deulino with Russia, ending the war on positive terms and enabling him to look west. Sigismund III Vasa, while not innately interested in interfering in German politics, remembers disdainfully the long history of the Elector Alexander’s meddling with his rule, and his contributions to Sigismund’s deposition in Sweden by Charles IX. Free for the time being from his problems with Russia, he now readies to invade Silesia.

The general assumption is that hazards of war will prevent the Electors from convening to choose a new Emperor. That makes it all the more surprising when the electors representing the prince-bishops of Trier, Cologne and Mainz meet with the representative of the Elector of Brandenburg in Frankfurt and elect Ferdinand of Styria Emperor Ferdinand II, without Ferdinand’s representative even casting a questionable vote on the part of his master for himself as King of Bohemia. The Elector John Sigismund of Brandenburg explains to the Saxon ambassador afterwards that this was not in response to any inducements but a desire to prevent the critical destabilization of the empire and the start of a general war. Nonetheless, the Electress Eleonore is furious at the apparent betrayal.

In some respects, however, the point becomes moot when late in the year John Sigismund himself dies, succeeded by his son George Frederick.

Gabriel Bethlen successfully occupies Budapest. Encouraged by Christian and Eleonore to believe he will be allowed to keep Hungary for his prize if he fights the Habsburgs to the end from the east, he makes ready to attack Vienna.

The Spanish general Spinola leads an invasion of the Saxon lands in the west before the Elector’s brother William, recently returned from Hafen, is able to properly organize his own defensive force of 7,000 soldiers. Feigning an assault on the fortress of Julich, Spinola instead lands a successful blow on the Saxon army at Dusseldorf, which is sacked. At that point the Spanish army of some 16,000 faces the army of the Elector of Palatinate marching from the south, with 13,000 soldiers. The two armies face each other at Coblenz, where the Elector is defeated.

Elizabeth of Scotland continues with astonishing fecundity to bear children: she gives birth to another girl, also named Elizabeth.

1620

Realizing the situation in the Rhineland is rapidly degrading by the day, Eleonore pleads with Frederick Augustus to intervene but finds him unwilling to break his truce with Spain prematurely. At that point, Eleonore wins the permission of Christian to go on a foreign mission to win military assistance. Having a longstanding friendship with Henry IV of France, she undertakes to travel to France overland in the company of the French ambassador, disguised as a serving-woman.

Eleonore is scarcely out of Wittenberg when word arrives of an imminent Polish invasion. Albert leads his army into Lusatia and camps near Cottbus, anticipating a Polish drive into Lusatia or Silesia.

Instead, Sigismund III Vasa and Ferdinand II reach an accommodation with the Elector George Frederick of Brandenburg that entails a shocking betrayal by the Elector of his mother, Eleonore, and the other Wettins: George Frederick agrees to permit the Polish army to cross his territory in exchange for the promise of the lands of Lower Saxony, which would allow Brandenburg to stretch to the North Sea. The Polish army of 30,000 is passing through Berlin by the time Albert understands he has been outmaneuvered.

Sensing they cannot take Wittenberg outright just yet, the Polish army wheels west in an effort to take Madgeburg and draw out the Saxon forces from their defenses. They defeat the skeleton defensive force of undertrained militiamen at Halberstadt and lay siege to Madgeburg, preliminary to attacking Wittenberg itself.

In Bohemia, Count Tilly makes another attempt at Prague. The Elector Christian intercepts his forces at Pribram. The result is once again a narrow and indecisive defeat for Tilly, who retreats to Strakonice. Sensing the opportunity to gain decisive advantage, the Elector Christian lays siege to Strakonice and plans to make use of his army’s extensive siege experience from the Dutch Rebellion and the War of the Julich Succession. However, he is forced to raise the siege when word reaches him of the Polish invasion and the Saxon defeat at Halberstadt.

Leaving his Bohemian volunteers behind to defend Prague under the generalship of Count Thurn, he races north to intercept the Poles.

In a stroke of luck for the Saxons, Gabriel Bethlen at this moment defeats the Austrians at Pressburg, requiring Tilly himself to break off his offensive against Prague to withdraw and defend Vienna.

Finally, Eleonore arrives in Paris only to find that King Henry IV has died, and his successor Louis XIII unwilling to eager to her proposal for a partition of the Netherlands between the rebels and France in exchange for French involvement in the war against the Habsburgs. Soon afterwards, she receives word of the defeat at Halberstadt, triggering one of her few public displays of tears in her long public life.

In the west, Spinola finds himself unable to take any of the important fortresses guarding the Rhine, as William’s forces harass his own without venturing open combat. Finally, Frederick of the Palatinate and William of Saxony together manage to fight Spinola to a draw in the Battle of the Lippe.