You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

TLIAW: Memorias de nuestros padres

- Thread starter Nanwe

- Start date

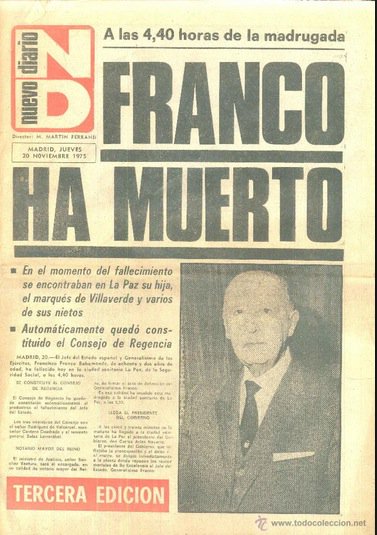

Generalíssimo Francisco Franco continues his heroic efforts to remain dead.

And, from a safe distance on the other side of the Atlantic, nothing of value was lost.

***

Extract from "Spanish Politics: An Introduction" by José María Domínguez Castro

The Spanish right-wing - that is excluding the regionalist and peripheral nationalist right-wing formations - is divided into two parties: The Democratic Centre Union (UCD) and the more right-wing Alianza Popular (People's Alliance) (1). A very considerable amount of research has been undertaken to study the fractious internal organisation of the UCD. This chapter seeks to categorise and provide a brief explanation of the various internal currents of the party, their leaders and an overview of their ideology (or lack thereof).

Suarism, or more accurately post-Suarism is perhaps the most complicated of all the various tendencies of the UCD to pin point. Although the UCD has never been a party of clear-cut ideological currents, but rather of personalities and power clusters in certain provinces or regions, Suarism is perhaps even harder to classify. According to former UCD Minister and well-known Suarist, Rafael Arias Salgado, Suarism is "not so much an ideology, but a political style, a connection with the people's needs and its expression in their own terms". In this the term does quite accurately reflect the political trajectory of the former Prime Minister: From small-c conservative in the early 70s, he moved towards the left by the early 80s and following his resignation, he bounced somewhat back to the right, perhaps under the influence of his deeply religious wife. As a result, the most accurate - and consequently the most ambiguous - appellative for it could be a 'populistic centrism with elements of Spanish nationalism' and a rhetoric which stresses compromise-building and consensus-seeking with the forces to the left of the UCD. In this sense it is difficult to know when a UCD politician is a Suarist as the recourse to the rhetoric type of the consensus is practically an everyday device of the party's politicians. However bona fide Suarists emphasise economic issues over social ones - as this is where the lines between right- and left-wing Suarists are drawn - and the current favours economic interventionism and the development of a bread-winner-centred welfare state. Economically then, the Suarists could be classed as a secularised version of the Christian democrats of the UCD. But it is however more complicated, because as whereas most of the UCD is strongly pro-Atlantic, the Suarists have been traditionally much more weary of depending on the United States to determine Spain's foreign policy and to this day, many lament Calvo Sotelo's decision to join NATO in 1982.

As a result, Suarists are mostly determined by their rhetoric and their moderate speech combined with references to representing the people, a populist device. To this is combined references to the Patria and a centralist vision of Spain that puts them at odds with either the autonomists within (like the relationship between Suárez and Manuel Clavero Arévalo) or without the UCD (exemplified by the relationship between Suárez and Catalan President Jordi Pujol). This attitude is perhaps best exemplified by Suárez himself:

It is important to note, however, that neither Suárez nor other Suarist politicians have allowed this rhetoric and unitary conception of the national identity to stand in the way of developing political consensus or reaching political deals. Perhaps the best example was the support given by Suarist leader of Centristes de Catalunya, Eduard Punset to the PDC government of Xavier Trias in 1999.

The Suarist current has however suffered from the retreat of Suárez from the public eye and has lost its position as one of the biggest currents in the post-Cold War environment. Nevertheless, major UCD politicians belonging to this current - or style - are Cristina Cifuentes or Alberto Ruíz-Gallardón among others.

The UCD's centrist current, unlike what its name might suggest, is not located in the political centre, a particularly nebulous term in Spain where centrism usually identifies politicians that would traditionally be placed in the centre-right. Instead, the centrist current is the direct descendant of the 'azules' of the Transition. This current is formed by former civil servants from the Grand Corps of the State, the elite of Spain's civil service and have a technocratic attitude to the governing of the country. Traditionally this current has provided the ministers for those portfolios seen as too compromising for the more politically-refined currents.

Due to this lack of clear-cut ideology, the centrists tend to move across the spectrum based on what appears to be the majority position of the party regarding key economic and social issues and as a general rule, given the personalism inherent to a ideology-deficient and ministrism-prone current, has shifted towards a tacit support for social liberalising policies while supporting some elements of neoliberalism, although with important caveats regarding the reduction of the State's apparatus. This current tends to be considered unpositioned regarding the ongoing debate about the reform of the Constitution to provide the regions with legislative initiative a a completion of the deconcentration process and a move towards larger autonomy for the non-historic regions.

Historical key members included Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo or Rodolfo Martín Villa, whereas modern-day some of its most important members are Jose Vicente Herrera, María Jesús San Segundo, Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría or brothers Juan Víctor Sevilla and Jordi Sevilla.

The Spanish right-wing - that is excluding the regionalist and peripheral nationalist right-wing formations - is divided into two parties: The Democratic Centre Union (UCD) and the more right-wing Alianza Popular (People's Alliance) (1). A very considerable amount of research has been undertaken to study the fractious internal organisation of the UCD. This chapter seeks to categorise and provide a brief explanation of the various internal currents of the party, their leaders and an overview of their ideology (or lack thereof).

[...]

Suarism, or more accurately post-Suarism is perhaps the most complicated of all the various tendencies of the UCD to pin point. Although the UCD has never been a party of clear-cut ideological currents, but rather of personalities and power clusters in certain provinces or regions, Suarism is perhaps even harder to classify. According to former UCD Minister and well-known Suarist, Rafael Arias Salgado, Suarism is "not so much an ideology, but a political style, a connection with the people's needs and its expression in their own terms". In this the term does quite accurately reflect the political trajectory of the former Prime Minister: From small-c conservative in the early 70s, he moved towards the left by the early 80s and following his resignation, he bounced somewhat back to the right, perhaps under the influence of his deeply religious wife. As a result, the most accurate - and consequently the most ambiguous - appellative for it could be a 'populistic centrism with elements of Spanish nationalism' and a rhetoric which stresses compromise-building and consensus-seeking with the forces to the left of the UCD. In this sense it is difficult to know when a UCD politician is a Suarist as the recourse to the rhetoric type of the consensus is practically an everyday device of the party's politicians. However bona fide Suarists emphasise economic issues over social ones - as this is where the lines between right- and left-wing Suarists are drawn - and the current favours economic interventionism and the development of a bread-winner-centred welfare state. Economically then, the Suarists could be classed as a secularised version of the Christian democrats of the UCD. But it is however more complicated, because as whereas most of the UCD is strongly pro-Atlantic, the Suarists have been traditionally much more weary of depending on the United States to determine Spain's foreign policy and to this day, many lament Calvo Sotelo's decision to join NATO in 1982.

As a result, Suarists are mostly determined by their rhetoric and their moderate speech combined with references to representing the people, a populist device. To this is combined references to the Patria and a centralist vision of Spain that puts them at odds with either the autonomists within (like the relationship between Suárez and Manuel Clavero Arévalo) or without the UCD (exemplified by the relationship between Suárez and Catalan President Jordi Pujol). This attitude is perhaps best exemplified by Suárez himself:

«El proceso autonómico tampoco puede ser una vía para la destrucción del sentimiento de pertenencia de todos los españoles a una Patria común. La autonomía no puede, por tanto, convertirse en un vehículo de exacerbación nacionalista, ni mucho menos debe utilizarse como palanca para crear nuevos nacionalismos particularistas» (2)

It is important to note, however, that neither Suárez nor other Suarist politicians have allowed this rhetoric and unitary conception of the national identity to stand in the way of developing political consensus or reaching political deals. Perhaps the best example was the support given by Suarist leader of Centristes de Catalunya, Eduard Punset to the PDC government of Xavier Trias in 1999.

The Suarist current has however suffered from the retreat of Suárez from the public eye and has lost its position as one of the biggest currents in the post-Cold War environment. Nevertheless, major UCD politicians belonging to this current - or style - are Cristina Cifuentes or Alberto Ruíz-Gallardón among others.

[...]

The UCD's centrist current, unlike what its name might suggest, is not located in the political centre, a particularly nebulous term in Spain where centrism usually identifies politicians that would traditionally be placed in the centre-right. Instead, the centrist current is the direct descendant of the 'azules' of the Transition. This current is formed by former civil servants from the Grand Corps of the State, the elite of Spain's civil service and have a technocratic attitude to the governing of the country. Traditionally this current has provided the ministers for those portfolios seen as too compromising for the more politically-refined currents.

Due to this lack of clear-cut ideology, the centrists tend to move across the spectrum based on what appears to be the majority position of the party regarding key economic and social issues and as a general rule, given the personalism inherent to a ideology-deficient and ministrism-prone current, has shifted towards a tacit support for social liberalising policies while supporting some elements of neoliberalism, although with important caveats regarding the reduction of the State's apparatus. This current tends to be considered unpositioned regarding the ongoing debate about the reform of the Constitution to provide the regions with legislative initiative a a completion of the deconcentration process and a move towards larger autonomy for the non-historic regions.

Historical key members included Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo or Rodolfo Martín Villa, whereas modern-day some of its most important members are Jose Vicente Herrera, María Jesús San Segundo, Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría or brothers Juan Víctor Sevilla and Jordi Sevilla.

Notes:

(1) Fraga disliked Suárez far too much for him to ever join a party created by Suárez and which did not fit into his very clear-cut socio-political vision of Spain.

(2) "The autonomic process cannot either become a way for the destruction of all the Spaniards' sense of belonging to a common Motherland. Hence, the autonomy can not become a vehicle of nationalist exacerbation, and it certainly can not be used as a lever to create new particularistic nationalisms."

(2) "The autonomic process cannot either become a way for the destruction of all the Spaniards' sense of belonging to a common Motherland. Hence, the autonomy can not become a vehicle of nationalist exacerbation, and it certainly can not be used as a lever to create new particularistic nationalisms."

Last edited:

Dr. Strangelove

Banned

That is certainly very interesting. How much of that was also true in OTL?

It is true that UCD was a cluster of competing personalities and currents with little ideology, taking whatever it wanted from moderate right and left. Suárez was a former falangist that ended sympathinzing with the Non Aligned Movement, etc.

It is not true that all those currents managed to coalesce into a stable party instead of backstabbing and trampling each other until the party nuked itself into irrelevance from 1982 on.

Dunno why, but Cifuentes is, IMHO, too right to be in the UCD.

I'm enjoying this reading so far, by the way!

I'm enjoying this reading so far, by the way!

Dolores a Madrid

The years 1976 and 1977 would be marked by a series of sudden shocks that would change the political face of Spain from the 40 years of National-Catholicism, virulent Spanish nationalism and equally virulent anti-Communism. The Suárez government undertook soon after its formation the task of reforming the Penal Code as a first step towards relaxing the conditions to be met in order to form political 'associations', as parties were known in the Francoist parlance. However, the most important events of the year 1976 took place during the summer, when the 'Ley para la Reforma Política' was drafted (July) and presented before the Council of Ministers on August 24th. Alongside this Fundamental Law, meant to alter the Constitution of the Francoist regime by providing for a directly-elected parliament through universal suffrage, doing away with the so*called 'organic democracy' of the Francoism and its election method in thirds (1).

At the same time, and in preparation for the elections, the various opposition parties started to organise themselves and present themselves before the public. In July 1976, the PCE held a Congress in Rome where it named the members of its Executive Committee and declared its intention to return to Spain and to fight for democracy, leaving behind its intention of calling for the rise of the working class against the regime. On August 10th, Suárez would meet with the leader of the PS, Felipe González in secret as part of the series of contacts between the Prime Minister and the opposition that would be held during the year and later on a formal basis, after January 1977. Starting in September, Suárez would start informal contacts with Carrillo and with Josep Tarradellas.

But late 1976 and in particular 1977 until the elections in June was characterised by a series of waves terrorist attacks from ETAm, ETApm, the FRAP, the GRAPO and the various organisations from the far-right, perhaps the most prominent being Guerrilleros de Cristo-Rey. In this radicalised environment, ETApm's strategy of provoking a military reaction was opposed by one of its leader, Pertur, who would be murdered by his own colleagues for his preference for a political solution and his moderation.

On November 16th, the Cortes would meet to vote on the bill of the Ley para la Reforma Política. As a show of strength, the opposition, now organised in the P.O.D. (Plataforma de la Oposición Democrática) would organise a general strike on the 12th. However, it was a failure, as only about 450,000 workers out of a 13 million workforce would strike, but it forced the Government to reckon the capacity of the opposition and serve as a precedent to hold talks. On the day of the vote, 425 procuradores voted 'Yes', 59 'No's and 13 abstained. This moment is to this day known as the 'harakiri' of the Francoist Cortes. From that moment onwards, the Government started a campaign calling for massive participation in the referendum provided by the Law for its acceptance as a part of the Constitution of the Francoist Regime. A massive 'Yes' vote would boost and increase the legitimacy of the Suárez government and its programme of radical reform of the Regime.

In the weeks previous to the vote, held on December 15th, the various opposition forces showed their presence while calling for citizens to abstain, as they perceived the referendum to lack sufficient democratic validity. Between the 5th and the 8th, the PS held its first Congress, led by Felipe González and Alfonso Guerra, and supported by Willy Brandt (2). On the 10th, Carrillo would appear before the press in an apartment in Madrid, to the embarrassment of the Government.

On the day of the referendum, over 75% of the population voted, and of them, over 94% voted for the 'Yes'. The approval of the Government's project by the majority of the population boosted the legitimacy and support of the Government, vis-à-vis both the democratic opposition and the Francoist orthodoxy, still strong in the institutions of the State. Following his victory, Suárez would meet, on January 11th, with the representatives of the P.O.D., the Commission of the Nine (3) to find a common ground between the Government's plan and the demands of the opposition. At the same time, Suárez would travel to Catalonia, where it promised the establishment of a 'Consell General de Catalunya', which would draft an Estatut as well as the co-official status of Catalan in Catalonia from that moment onwards.

The week between the 23th and the 30th January was to be one of the moments that shook Spain and menaced the democratic trajectory of the country. This week was immortalised by Juan Antonio Bardem in the film 'Siete días de enero'. The week started with the murder of a student during a pro-democracy demonstration by far-right activists on the 23rd. The following day, in a march organised in response to this murder, one student would be killed by the police. This was not to be the end of the 24th, instead, at around 10, an armed group of far-right militants would enter a labour law firm's office in Atocha and kill 10 people (4). On the following day, the PCE, showing its mass support and its disciplined base, would hold a massive funeral for the victims in total and absolute silence. This is considered a turning point in the PCE's battle for legalisation, as this show of self-restraint impressed many until then opposed to its presence in the political sphere.

After this moment, the PCE's pressure to be legalised before the elections in June was to mount. In secret, on the 27th of February, Carillo and Suárez would meet each other in a house outside Madrid for hours. Out of this meeting, it is said, that came the decision to legalise the party, contrary to Suárez's original intentions to wait until after the elections. And perhaps more importantly, the good relationship and bond built by both during that fateful afternoon (later evening, and by the end, 4 am) was to be a critical element in the draft of the Constitution after June.

On the 9th of April, during the Holy Week the PCE would be legalised, following a favourable opinion from the Junta de Fiscales, the governing body of the Public Ministry. The reactions to this decision were tremendous: The minister of the Navy resigned and the Army's governing organ, the Consejo Superior del Ejército published a note where it showed its reticence to the decision and only accepted it as a necessity of the superior interest of the Nation, despite considerable opposition to it. The note was accompanied by a second, non-official note that was much more critical of the decision and hinted at the possibility of an Army's coup.

As a result, on the 14th April, in the first meeting of the PCE's Central Committee, Carrillo would proclaim the PCE's adherence to the flag, the monarchy and the 'unity of Spain', in an attempt to shore up the Government and try to calm the fears of the Army regarding the PCE. From that moment onwards, the PCE has always had a Spanish flag alongside the red flag in its meetings (5).

At the same time, and in preparation for the elections, the various opposition parties started to organise themselves and present themselves before the public. In July 1976, the PCE held a Congress in Rome where it named the members of its Executive Committee and declared its intention to return to Spain and to fight for democracy, leaving behind its intention of calling for the rise of the working class against the regime. On August 10th, Suárez would meet with the leader of the PS, Felipe González in secret as part of the series of contacts between the Prime Minister and the opposition that would be held during the year and later on a formal basis, after January 1977. Starting in September, Suárez would start informal contacts with Carrillo and with Josep Tarradellas.

But late 1976 and in particular 1977 until the elections in June was characterised by a series of waves terrorist attacks from ETAm, ETApm, the FRAP, the GRAPO and the various organisations from the far-right, perhaps the most prominent being Guerrilleros de Cristo-Rey. In this radicalised environment, ETApm's strategy of provoking a military reaction was opposed by one of its leader, Pertur, who would be murdered by his own colleagues for his preference for a political solution and his moderation.

On November 16th, the Cortes would meet to vote on the bill of the Ley para la Reforma Política. As a show of strength, the opposition, now organised in the P.O.D. (Plataforma de la Oposición Democrática) would organise a general strike on the 12th. However, it was a failure, as only about 450,000 workers out of a 13 million workforce would strike, but it forced the Government to reckon the capacity of the opposition and serve as a precedent to hold talks. On the day of the vote, 425 procuradores voted 'Yes', 59 'No's and 13 abstained. This moment is to this day known as the 'harakiri' of the Francoist Cortes. From that moment onwards, the Government started a campaign calling for massive participation in the referendum provided by the Law for its acceptance as a part of the Constitution of the Francoist Regime. A massive 'Yes' vote would boost and increase the legitimacy of the Suárez government and its programme of radical reform of the Regime.

In the weeks previous to the vote, held on December 15th, the various opposition forces showed their presence while calling for citizens to abstain, as they perceived the referendum to lack sufficient democratic validity. Between the 5th and the 8th, the PS held its first Congress, led by Felipe González and Alfonso Guerra, and supported by Willy Brandt (2). On the 10th, Carrillo would appear before the press in an apartment in Madrid, to the embarrassment of the Government.

On the day of the referendum, over 75% of the population voted, and of them, over 94% voted for the 'Yes'. The approval of the Government's project by the majority of the population boosted the legitimacy and support of the Government, vis-à-vis both the democratic opposition and the Francoist orthodoxy, still strong in the institutions of the State. Following his victory, Suárez would meet, on January 11th, with the representatives of the P.O.D., the Commission of the Nine (3) to find a common ground between the Government's plan and the demands of the opposition. At the same time, Suárez would travel to Catalonia, where it promised the establishment of a 'Consell General de Catalunya', which would draft an Estatut as well as the co-official status of Catalan in Catalonia from that moment onwards.

The week between the 23th and the 30th January was to be one of the moments that shook Spain and menaced the democratic trajectory of the country. This week was immortalised by Juan Antonio Bardem in the film 'Siete días de enero'. The week started with the murder of a student during a pro-democracy demonstration by far-right activists on the 23rd. The following day, in a march organised in response to this murder, one student would be killed by the police. This was not to be the end of the 24th, instead, at around 10, an armed group of far-right militants would enter a labour law firm's office in Atocha and kill 10 people (4). On the following day, the PCE, showing its mass support and its disciplined base, would hold a massive funeral for the victims in total and absolute silence. This is considered a turning point in the PCE's battle for legalisation, as this show of self-restraint impressed many until then opposed to its presence in the political sphere.

After this moment, the PCE's pressure to be legalised before the elections in June was to mount. In secret, on the 27th of February, Carillo and Suárez would meet each other in a house outside Madrid for hours. Out of this meeting, it is said, that came the decision to legalise the party, contrary to Suárez's original intentions to wait until after the elections. And perhaps more importantly, the good relationship and bond built by both during that fateful afternoon (later evening, and by the end, 4 am) was to be a critical element in the draft of the Constitution after June.

On the 9th of April, during the Holy Week the PCE would be legalised, following a favourable opinion from the Junta de Fiscales, the governing body of the Public Ministry. The reactions to this decision were tremendous: The minister of the Navy resigned and the Army's governing organ, the Consejo Superior del Ejército published a note where it showed its reticence to the decision and only accepted it as a necessity of the superior interest of the Nation, despite considerable opposition to it. The note was accompanied by a second, non-official note that was much more critical of the decision and hinted at the possibility of an Army's coup.

As a result, on the 14th April, in the first meeting of the PCE's Central Committee, Carrillo would proclaim the PCE's adherence to the flag, the monarchy and the 'unity of Spain', in an attempt to shore up the Government and try to calm the fears of the Army regarding the PCE. From that moment onwards, the PCE has always had a Spanish flag alongside the red flag in its meetings (5).

Notes:

(1) Just irrelevant, but I found it interesting to explain the system: One third by the municipalities (so basically stuffed by administration's candidates), another third by the unions (so again, by Francoists of the Sindicato Vertical) and a last third directly-"elected" by the household heads over 30 (so married men over 30), which were rigged to ensure that this democracy worked appropriately.

(2) This is an important change from OTL. OTL, the PSOE had the support of the entire Socialist International, so the conference was home to Brandt, but also Palme, Foot, Nenni, Soares among other international socialism leaders.

(3) Formed by a representative of the PSP, one for the PS, one for the PCE, one social-democrat, one liberal, one Christian democrat, one Basque nationalist, one Catalan nationalist, one Galician nationalist and one syndical representative, who could express his opinion but not vote, and who was a member of CCOO, hence it could be considered a second Communist representative.

(4) OTL, it was 9. If anyone can guess who else died (because it is not a random person), they will be rewarded .

.

(5) Unlike OTL, where after the carrillistas were expelled from the party, there was a return to the Republican flag.

(2) This is an important change from OTL. OTL, the PSOE had the support of the entire Socialist International, so the conference was home to Brandt, but also Palme, Foot, Nenni, Soares among other international socialism leaders.

(3) Formed by a representative of the PSP, one for the PS, one for the PCE, one social-democrat, one liberal, one Christian democrat, one Basque nationalist, one Catalan nationalist, one Galician nationalist and one syndical representative, who could express his opinion but not vote, and who was a member of CCOO, hence it could be considered a second Communist representative.

(4) OTL, it was 9. If anyone can guess who else died (because it is not a random person), they will be rewarded

(5) Unlike OTL, where after the carrillistas were expelled from the party, there was a return to the Republican flag.

That is certainly very interesting. How much of that was also true in OTL?

It is true that UCD was a cluster of competing personalities and currents with little ideology, taking whatever it wanted from moderate right and left. Suárez was a former falangist that ended sympathinzing with the Non Aligned Movement, etc.

It is not true that all those currents managed to coalesce into a stable party instead of backstabbing and trampling each other until the party nuked itself into irrelevance from 1982 on.

As Doc said, the UCD nuked itself into irrelevance. One of the rare cases when the infighting precedes the electoral defeat and not the other way around. As Suárez himself admitted (even boasted), the UCD was home to liberals, social democrats, conservatives, Christian democrats, social democrats and regionalists. A madman's house, basically, held together by the glue of power.

Thanks, Doc. Certainly makes it all the more interesting to see what evolution a 'stable' UCD takes.

I know I haven't yet focused much on the PCE, later to be renamed, but let's not forget that the UCD is not living in the vacuum.

Keep it up, Nanwe!

Cheers! Will do!

Dunno why, but Cifuentes is, IMHO, too right to be in the UCD.

I'm enjoying this reading so far, by the way!

Thanks! Are you sure? I'm not quite sure as to the political positions of Cifuentes herself, but her rhetoric, which is what I mostly focused on defining what a Suarist is, seems much more conciliatory than many other PP leaders, even before coming to power in the CAM.

By the way, I'm surprised no one commented on the foreshadowing in Catalonia or Punset's presence.

Goldstein

Banned

(4) OTL, it was 9. If anyone can guess who else died (because it is not a random person), they will be rewarded.

Well, butterflies aside, we can now say for sure that Manuela Carmena won't become mayor of Madrid, nor she will become anything that involves being alive

By the way, I'm surprised no one commented on the foreshadowing in Catalonia or Punset's presence.

I was more surprised about the "Centrists of Catalonia" being a thing, than about the presence of Punset. In a really Mary-sueish onesot scenario of mine, I even made him PM.

Well, butterflies aside, we can now say for sure that Manuela Carmena won't become mayor of Madrid, nor she will become anything that involves being alive

True. I only found out through an old interview I read of her, and I thought that well, it is a pity since she's an interesting character, but also, why not? I don't wish her any bad in any case.

But I also wanted to showcase how many important politicians are still closely linked to this period. For instance, say that Carmena wasn't killed TTL, maybe she could become a Minister of Justice (or of Equality?), once the post-Cold War PCE (under new, appropriate branding) comes to power.

I was more surprised about the "Centrists of Catalonia" being a thing, than about the presence of Punset. In a really Mary-sueish onesot scenario of mine, I even made him PM.

Centristes de Catalunya-UCD was indeed the name of UCD in Catalonia formed by the very moderate Catalanists from Unió that didn't want to join CiU and the UCD's own branch. And I don't think it's that utterly impossible, Punset was after a Minister OTL, so there you go.

By the way, watch out for Catalonia because there the left-wing is going to be totally different. Not only the PSUC will dominate, but the PS(OE) won't sacrifice its branch there to make a pact with Catalanist social democrats to form the PSC, so something else will happen.

More to come in the next instalment about the elections of 77. It'll cover the formations of the parties, also known as 'how Suárez and Cabanillas backstab Areilza to create the UCD out of the PP', which is not the same thing as CP/AP/FAP nor the PDP.

Last edited:

¡Habla, pueblo, habla!

The elections of 1977 were the first freely held in Spain since 1936, that ism in over 40 years. And it showed. Of all the parties that managed to obtain parliamentary representation in either chamber, only 5 had already had representation in the Cortes of the Republic: Unió, ERC, PCE-PSUC, PSOE and PNV. In particular, the centre and the right had not continued their pre-war formations, the CEDA. That is not to say that some of the politicians from the Republic did not go on, Gil Robles, for instance, would form Federación Popular Democrática (FPD), which would gain one seat in the elections of 77 (1).

As a result, the centre and the right-wing of Spanish politics had to be created from scratch. It was no easy task. Following the passing of the Ley de Asociaciones in 1975, and especially of the reform of the Penal Code in 1976, a myriad of parties, usually centred on a single post-Francoist or moderate opposition figure surged. There were so many it is hard to tell the exact amount, as many of them came and went as politicians considered them to be personal vehicles for power rather than ideological apparati. Amidst this seat of small parties, two came to the forefront. The first one was People's Alliance (AP), founded in 1976 through the merger of nine previous parties and led by Manuel Fraga Iribarne, previous Interior Minister under the Arias Navarro Governments and Information and Tourism Minister between 1962 and 1969. By his side, Cruz Martínez Esteruelas, Federico Silva Muñoz, Licinio de la Fuente, Laureano López Rodó and Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora (2). The party sought to carry the vote of what was known as 'sociological francoism' and tie those forces that could potentially support far-right forces to the democratic system. It sought to be the main party of the right. It was what Francisco Umbral termed 'la derecha asilvestrada'. (3)

In contrast to this right-wing, around the personalities of Jose María de Areilza and Pío Cabanillas - the father, not to be confounded with his son - (4) appeared the Partido Popular (People's Party) a party of the liberal right and the centre that also sought to become a majority option. The party was to be the seed of the future UCD. Although to get there, one major betrayal was needed. As a result of its more centrist orientation, its favourable position in polls and its desire to rally the 'derecha civilizada' (5), Suárez had been interested in the party for some time. On the occasion of the PP's first Congress in Madrid, a series of phone calls were exchanged between Pío Cabanillas and Moncloa, in which the latter promised the government's support and the potential leadership of Suárez - and his popularity - to the party if Areilza was sidelined from the party's leadership altogether. The reason for this was that Suárez - who originally was not sure as to whether to continue as Prime Minister after the 1977 election - wanted no major rival within the party as to solidify its support in a party, that based on its membership, would prove fractious. It would be the task of Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo to use the PP as a core to attract other moderate parties to form the UCD through the promise of governmental support and the popularity and charisma of the Prime Minister. This way, the UCD was to be created from the merger of sixteen political parties. Originally however, and until December 1977, the UCD would remain a coalition of parties and independents led by Suárez and not a single party.

On the left itself, the situation was only somewhat more clear. The PCE (and the PCUS in Catalonia) was the best organised of all the parties, and carried the badge of honour of having been the main opposition to the dictatorship for over forty years. As a result, the PCE, with its historic well-known leaders, such as Santiago Carrillo or Dolores Ubarruri stood in contrast to the other parties on the left, much smaller and without such significant advantages. However, the PCE's membership and followers were all far from Communists themselves, there were many 'progressives' and socialists amongst the party's ranks, and this was a factor taken into account by the party's leadership, which was quite moderated, helped in part by the good relationship between Carrillo and Suárez.

In between the UCD and the PCE was a field of socialist parties. The primary ones were the PSOE, with its history but lacking in effective leaders and having lost its touch with the Spanish reality after so many years of exile; the PS, founded by the renovadores from the PSOE and led by charismatic Felipe González. Alongside both, Enrique Tierno Galván's PSP. Together, however the three parties did not match the voting share of the PCE.

As for the election itself, the most voted party was the UCD, with 170 seats, followed by the PCE, with 109, the PS with 23, AP with 14 and the PSP, which obtained 9 deputies. One seat was obtained by the Christian democrats of FPD. The rest of seats were divided between the various regionalist forces: 11 for the PDPC, the main Catalan regionalist party, led by Jordi Pujol, the PNV with 8, UC-DCC (6), which obtained 2 seats and then EC, EE and CAIC (7).

As a result, the centre and the right-wing of Spanish politics had to be created from scratch. It was no easy task. Following the passing of the Ley de Asociaciones in 1975, and especially of the reform of the Penal Code in 1976, a myriad of parties, usually centred on a single post-Francoist or moderate opposition figure surged. There were so many it is hard to tell the exact amount, as many of them came and went as politicians considered them to be personal vehicles for power rather than ideological apparati. Amidst this seat of small parties, two came to the forefront. The first one was People's Alliance (AP), founded in 1976 through the merger of nine previous parties and led by Manuel Fraga Iribarne, previous Interior Minister under the Arias Navarro Governments and Information and Tourism Minister between 1962 and 1969. By his side, Cruz Martínez Esteruelas, Federico Silva Muñoz, Licinio de la Fuente, Laureano López Rodó and Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora (2). The party sought to carry the vote of what was known as 'sociological francoism' and tie those forces that could potentially support far-right forces to the democratic system. It sought to be the main party of the right. It was what Francisco Umbral termed 'la derecha asilvestrada'. (3)

In contrast to this right-wing, around the personalities of Jose María de Areilza and Pío Cabanillas - the father, not to be confounded with his son - (4) appeared the Partido Popular (People's Party) a party of the liberal right and the centre that also sought to become a majority option. The party was to be the seed of the future UCD. Although to get there, one major betrayal was needed. As a result of its more centrist orientation, its favourable position in polls and its desire to rally the 'derecha civilizada' (5), Suárez had been interested in the party for some time. On the occasion of the PP's first Congress in Madrid, a series of phone calls were exchanged between Pío Cabanillas and Moncloa, in which the latter promised the government's support and the potential leadership of Suárez - and his popularity - to the party if Areilza was sidelined from the party's leadership altogether. The reason for this was that Suárez - who originally was not sure as to whether to continue as Prime Minister after the 1977 election - wanted no major rival within the party as to solidify its support in a party, that based on its membership, would prove fractious. It would be the task of Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo to use the PP as a core to attract other moderate parties to form the UCD through the promise of governmental support and the popularity and charisma of the Prime Minister. This way, the UCD was to be created from the merger of sixteen political parties. Originally however, and until December 1977, the UCD would remain a coalition of parties and independents led by Suárez and not a single party.

On the left itself, the situation was only somewhat more clear. The PCE (and the PCUS in Catalonia) was the best organised of all the parties, and carried the badge of honour of having been the main opposition to the dictatorship for over forty years. As a result, the PCE, with its historic well-known leaders, such as Santiago Carrillo or Dolores Ubarruri stood in contrast to the other parties on the left, much smaller and without such significant advantages. However, the PCE's membership and followers were all far from Communists themselves, there were many 'progressives' and socialists amongst the party's ranks, and this was a factor taken into account by the party's leadership, which was quite moderated, helped in part by the good relationship between Carrillo and Suárez.

In between the UCD and the PCE was a field of socialist parties. The primary ones were the PSOE, with its history but lacking in effective leaders and having lost its touch with the Spanish reality after so many years of exile; the PS, founded by the renovadores from the PSOE and led by charismatic Felipe González. Alongside both, Enrique Tierno Galván's PSP. Together, however the three parties did not match the voting share of the PCE.

As for the election itself, the most voted party was the UCD, with 170 seats, followed by the PCE, with 109, the PS with 23, AP with 14 and the PSP, which obtained 9 deputies. One seat was obtained by the Christian democrats of FPD. The rest of seats were divided between the various regionalist forces: 11 for the PDPC, the main Catalan regionalist party, led by Jordi Pujol, the PNV with 8, UC-DCC (6), which obtained 2 seats and then EC, EE and CAIC (7).

Notes:

(1) They did not OTL, but barely and to everyone's surprise, since the FPD's Christian democrats had been an integral part of the opposition movement.

(2) These were Francoist middle-to-heavy weights (especially López Rodó). Cruz Martínez Esteruelas was Education Minister between 1974 and 1975, Federico Silva Muñoz was Public Works Minister (1967-70), Licinio de la Fuente was Labour Minister (1970-75), Laureano López Rodó was Foreign Affairs Minister (1973-74) and Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora was the Public Works Minister between 1970 and 1974.

(3) Translates to the 'forest right-wing' or the 'wild right-wing'.

(4) This two were also important Francoist ministers, although much more aperturistas. Areilza was the poster 'boy' for those who, like the Grupo Tácito or the liberal press, sought a deep reform of the Francoist system.

(5) 'Civilised right-wing'. Although it could also gather what Umbral termed the 'derecha AZCA'. AZCA being the main business district of Madrid.

(6) A secondary right-wing Catalanist party that would later split and merge with Convergència or with the UCD. It was basically Unió, except their less Catalanist members would merge with the UCD to create Centristes de Catalunya-UCD.

(7) EC: Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya and some minor groups.

EE: Euzkadiko Ezkerra. A left-wing Basque nationalist group, derived from ETApm's moderates.

CAIC: Candidatura Aragonesa Independiente de Centro. A small party that had split off from the UCD. Basically, the forerunners of the PAR.

(2) These were Francoist middle-to-heavy weights (especially López Rodó). Cruz Martínez Esteruelas was Education Minister between 1974 and 1975, Federico Silva Muñoz was Public Works Minister (1967-70), Licinio de la Fuente was Labour Minister (1970-75), Laureano López Rodó was Foreign Affairs Minister (1973-74) and Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora was the Public Works Minister between 1970 and 1974.

(3) Translates to the 'forest right-wing' or the 'wild right-wing'.

(4) This two were also important Francoist ministers, although much more aperturistas. Areilza was the poster 'boy' for those who, like the Grupo Tácito or the liberal press, sought a deep reform of the Francoist system.

(5) 'Civilised right-wing'. Although it could also gather what Umbral termed the 'derecha AZCA'. AZCA being the main business district of Madrid.

(6) A secondary right-wing Catalanist party that would later split and merge with Convergència or with the UCD. It was basically Unió, except their less Catalanist members would merge with the UCD to create Centristes de Catalunya-UCD.

(7) EC: Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya and some minor groups.

EE: Euzkadiko Ezkerra. A left-wing Basque nationalist group, derived from ETApm's moderates.

CAIC: Candidatura Aragonesa Independiente de Centro. A small party that had split off from the UCD. Basically, the forerunners of the PAR.

Last edited:

I love it, too! Keep it going!

About Cifuentes. Yes, I have that feeling about her, but perhaps the different path taken by Spain may have changed her mind, so, why not having her in UCD...

About Cifuentes. Yes, I have that feeling about her, but perhaps the different path taken by Spain may have changed her mind, so, why not having her in UCD...

Goldstein

Banned

Still following this TL, still thinking it's great. I love how the subtle differences slowly permeate.

I have to say, though, that even if I see how the fragmentation of the left benefits the PCE and prevents a future election outcome remotely resembling that of OTL 1982, I still can't see how that prevents the UCD from blowing itself up.

But that doesn't mean incredulity, at all. It means I'll love to figure it out.

I have to say, though, that even if I see how the fragmentation of the left benefits the PCE and prevents a future election outcome remotely resembling that of OTL 1982, I still can't see how that prevents the UCD from blowing itself up.

But that doesn't mean incredulity, at all. It means I'll love to figure it out.

Wow, that's a big PCE!

Btw, have you given any thought to the Galicianist parties? For example IOTL the PSG (Partido Socialista Galego, Beiras's party) was very close to the 3% barrier (2.41%), but no cigar, which made the party collapse, and most left and went to the PSOE. With a more divided Socialist field, it might have a chance to get representation. Sadly, i don't know who would have been the MP. Probably Beiras, as there was no autonomic parliament yet.

Btw, trivia: Did you know that back in the day, the ex-mayor of Coruña, Paco Vázquez, infamous centralist, once was doubting between joining the PSOE or joining the PSG (which was openly nationalist)?

Btw, have you given any thought to the Galicianist parties? For example IOTL the PSG (Partido Socialista Galego, Beiras's party) was very close to the 3% barrier (2.41%), but no cigar, which made the party collapse, and most left and went to the PSOE. With a more divided Socialist field, it might have a chance to get representation. Sadly, i don't know who would have been the MP. Probably Beiras, as there was no autonomic parliament yet.

Btw, trivia: Did you know that back in the day, the ex-mayor of Coruña, Paco Vázquez, infamous centralist, once was doubting between joining the PSOE or joining the PSG (which was openly nationalist)?

Goldstein

Banned

Oh, BTW:

Was the PSOE unable to get representation in the Congress? Because the first lines of the entry seem to indicate otherwise.

As for the election itself, the most voted party was the UCD, with 170 seats, followed by the PCE, with 109, the PS with 23, AP with 14 and the PSP, which obtained 9 deputies. One seat was obtained by the Christian democrats of FPD. The rest of seats were divided between the various regionalist forces: 11 for the PDPC, the main Catalan regionalist party, led by Jordi Pujol, the PNV with 8, UC-DCC (6), which obtained 2 seats and then EC, EE and CAIC (7).

Was the PSOE unable to get representation in the Congress? Because the first lines of the entry seem to indicate otherwise.

Share: