THE IRON SICILIAN

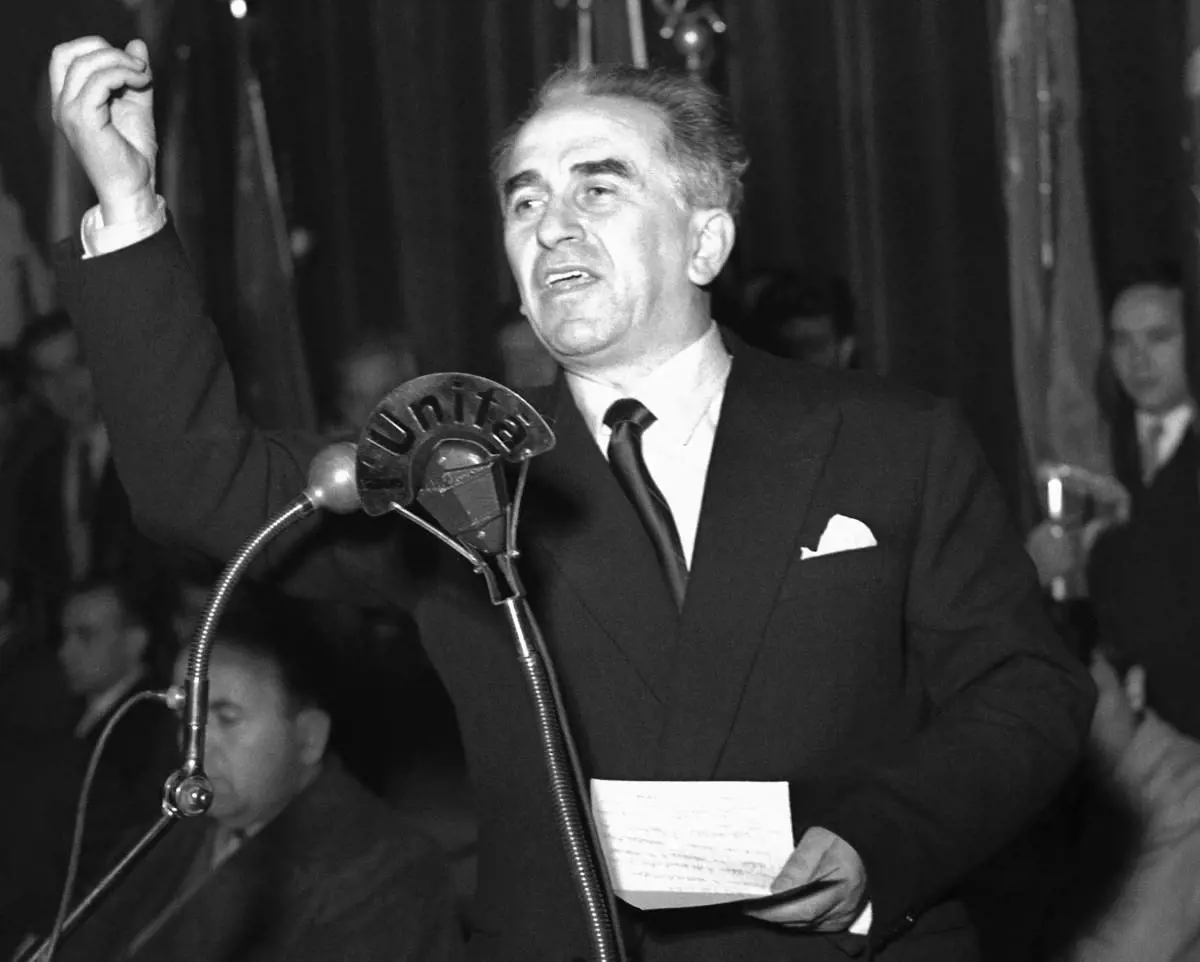

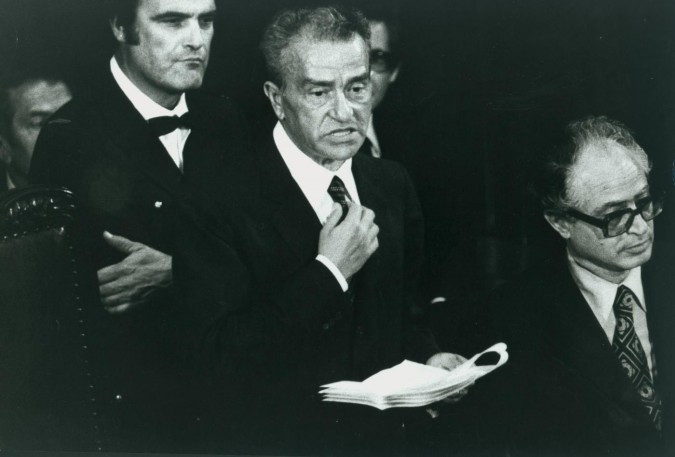

MARIO SCELBA

The Iron Sicilian

There are many factors that determined the outbreak of the Second Italian Civil War in 1948. First, Italy had suffered greatly during the Second World War. Much of its cities and infrastructure had been reduced to ruins, and entire families had been torn apart by the first civil war.

France's annexation of the Aosta Valley had only strengthened the communist and neo-fascist groups active in the country, both eager to exploit national humiliation and popular anger to control the government.

Finally, Italy had had the misfortune of having Mario Scelba as the new Prime Minister. Yet, at the time of his rise to power there was much hope in the young politician.

Scelba had been Alcide De Gasperi's right-hand man for years, becoming one of the founders of the Christian Democrats, and many considered him a hero for his support to various opposition groups, active during the Fascist government.

For this reason, Scelba was unanimously elected new leader of the DC after De Gasperi had been executed by the fascists in 1943.

In the first three years of his government, Scelba achieved many important results , including the abolition of the Savoyard monarchy and the full reintegration of the peninsula into the western political and diplomatic world.

Furthermore, in the immediate post-war period, the new Prime Minister initiated both the slow and inexorable regrowth of the Italian economy, and the first reconstruction works.

After more than twenty years of fascist dictatorship and two years of civil war, it therefore seemed that the worst was over for Italy. Unfortunately, this peace was only apparent.

Despite the efforts of Rome and the Allies to stabilize the political situation, Italy was still deeply divided. Many communist partisans had simply refused to lay down their weapons, forming various paramilitary groups hostile to the government, and some right-wing political groups still wanted to restore the old fascist regime.

Scelba's flaw that worsened the situation to the point of no return was the very reason he was appointed head of the DC: his staunch opposition to communism. The young Prime Minister was apparently obsessed with the idea that the PCI and its allies represented a serious threat to Italy.

For this reason, Scelba had tried to exclude the PCI from the first National Liberation Committee, and had expelled Togliatti's party from the government in 1946.

His paranoia, however, only increased after the expulsion of Palmiro Togliatti and other leftist politicians. The outbreak of civil wars in China and Greece convinced the Prime Minister that all leftist parties had as their sole objective the overthrow of the established order and the creation of a dictatorship similar to the fascist one.

In Scelba's eyes, every single problem that that afflicted Italy was Togliatti's fault. Strikes by workers in the industrial regions and by peasants in the South, the formation of neo-fascist groups, and even the economic problems of the First Republic were part of the communist plan to discredit his government.

For this reason, Scelba sought to strengthen security inside the Italian republic. Under his rule, not only were the funds and the number of recruits destined for the police force increased, but many suspected communists and socialists were also dismissed outright from political institutions and the army.

Scelba's anti-communist paranoia was so strong that between 1947 and 1948 the Prime Minister prevented any investigation into the attacks by criminal groups against strikers and trade unionists active in South Italy. Scelba probably had no connection to these attacks, but he feared that admitting the political reasons behind these acts of violence would have increased the popularity of the PCI.

Paradoxically, it was precisely the measures adopted by Scelba that weakened his government and strengthened his political opponents. Scelba's inability or refusal to stop the violence against trade unionists and peasants in the South seriously compromised the popularity of the DC, to such an extent that some areas of southern Italy abandoned the party in favor of the PCI, the PSI or the new Front National of Giorgio Almirante and Alfredo Covelli.

Many of the expelled soldiers became part of the various left-wing or right-wing paramilitary groups, active in the peninsula after the war. The open hostility of the government against anyone considered a leftist subversive also prompted Pietro Nenni and Giuseppe Saragat to ally with Togliatti to form the Fronte Nazionale Popolare (Popular Democratic Front).

Not only did Scelba's paranoia unite all of his left-wing opponents, but it also irreversibly divided the DC. In 1947, Giovanni Gronchi and a fairly large number of parliamentarians abandoned the DC to found Democrazia Popolare (Popular Democracy), stating that Scelba’s anti-comunist obsession was destroying the legacy of De Gasperi.

Internal tension reached its peak during the 1948 election. Togliatti and his allies were convinced that Scelba wanted to kill them, the Prime Minister feared that the Vatican too had been infiltrated by the communists, and Almirante accused both groups of being dangerous spies in the employ of Moscow and/or Washington.

The poll results were of particular concern to Scelba. While the DC was still the leading party in the South, much of Central and Northern Italy had started to prefer the DP and the FNP. Worse, even in South Italy the DC was losing precious votes to the neo-fascists/monarchists of the FN.

Even if the exact number could not be calculated, the DC was in danger of losing a large number of parliamentary seats after the election. In Scelba's eyes, the risk of an electoral victory of the National Popular Front was high.

In the end, Scelba's fears were not realized, as the DC remained the leading party in Italy. Unfortunately, Scelba also discovered that his party no longer had the number of seats in the Senate and Chamber needed to govern.

Indeed, none of the parties had won the number of seats required for the formation of a government. Less than two years after the birth of the First Republic, Italy was facing its first constitutional crisis.

Almost as a prelude to the subsequent conflict, the period between April and June 1948 is commonly known as "The Months of Lead", due to the massive violence that engulfed Italian cities.

In these two months, Italy found itself without a government, while Scelba and Togliatti both tried to convince the DP, now the third party in Italy, to ally with the DC or the FNP. At the same time, supporters of the DC and the FNP clashed with each other and with the police in the streets of the peninsula.

In the end, Togliatti became both the latest casualty of the Months of Lead and the first victim of the new civil war. On 14 July 1948 Antonio Pallante, a supporter of the overthrown monarchy, shot and killed the leader of the PCI.

How this assassination led to the outbreak of a new civil war depends on which version of events one decides to believe. According to the PCI and its allies, Togliatti's body was still warm as Scelba imposed martial law and ordered the arrest of the FNP leadership.

On the contrary, Scelba's supporters claim that the leaders of the FNP had already fled to Bologna well before Scelba knew of Togliatti's death. According to this version, Scelba would have imposed a state of emergency only because the FNP had declared war on his government, after forming the Second National Liberation Committee.

In any case, the Second Civil War became inevitable on July 4, 1948, when the troops stationed in Emilia Romagna refused orders from Rome, and swore allegiance to the government of Bologna.

In some ways, it is striking how the conflict in Italy mirrored in many aspects the civil wars in China and Greece. In all three cases, the Nationalist government was soon forced to retreat in the face of the advancing Communists/Socialists, due to its internal divisions and poor training of its troops.

The DP's decision to join the FNP in January 1949 determined the victory of Bologna. After this event, the main industrial cities of Northern Italy, including Milan, Trieste and Venice, fell into the hands of the SCLN.

Despite the huge economic and military aid from NATO, Scelba's troops thus ended up clashing with a better armed and organized army.

Rome was abandoned by Scelba and his government on 23 May 1951 and Naples, the last capital of the First Republic in mainland Italy, fell after three days of intense fighting on 10 September of the following year.

Scelba was ,however, far from any fight at the time. The Prime Minister had loaded what was left of his government onto a plane bound for his native Sicily two days before the start of the siege.

Since most of the Italian fleet had sunk or sided with his government, Scelba counted on turning Sicily and Sardinia into safe havens from which to plan an eventual reconquest of mainland Italy.

Scelba's latest plan was only half successful: although the two islands still host the government of the First Italian Republic, Scelba never arrived in Sicily.

Indeed, his plane exploded somewhere over the Strait of Messina about an hour after takeoff, killing all the passengers. It is still unclear whether it was a simple accident or whether Scelba was killed by his enemies or former allies.

In any case, his death had no particular consequences on the conclusion of the civil war. Even if Bologna had no way to invade Sicily and Sardinia, the military government, that had suceeded Scelba, could not in any way reverse the tide of the conflict.

Thanks to the mediation of the Yugoslav and French governments, a sort of ceasefire was signed by both sides in early 1953. As in China and Greece, the country's mainland came under the total control of the communist forces and their allies. Instead, the government that had opposed them had to take refuge on an island, under the constant protection of NATO.

Although neither Bologna nor Cagliari were willing to diplomatically recognize each other's rule, both were forced to accept this new status quo as they could not continue fighting.

Thus began a new era of the history of Italy.

The Iron Sicilian

There are many factors that determined the outbreak of the Second Italian Civil War in 1948. First, Italy had suffered greatly during the Second World War. Much of its cities and infrastructure had been reduced to ruins, and entire families had been torn apart by the first civil war.

France's annexation of the Aosta Valley had only strengthened the communist and neo-fascist groups active in the country, both eager to exploit national humiliation and popular anger to control the government.

Finally, Italy had had the misfortune of having Mario Scelba as the new Prime Minister. Yet, at the time of his rise to power there was much hope in the young politician.

Scelba had been Alcide De Gasperi's right-hand man for years, becoming one of the founders of the Christian Democrats, and many considered him a hero for his support to various opposition groups, active during the Fascist government.

For this reason, Scelba was unanimously elected new leader of the DC after De Gasperi had been executed by the fascists in 1943.

In the first three years of his government, Scelba achieved many important results , including the abolition of the Savoyard monarchy and the full reintegration of the peninsula into the western political and diplomatic world.

Furthermore, in the immediate post-war period, the new Prime Minister initiated both the slow and inexorable regrowth of the Italian economy, and the first reconstruction works.

After more than twenty years of fascist dictatorship and two years of civil war, it therefore seemed that the worst was over for Italy. Unfortunately, this peace was only apparent.

Despite the efforts of Rome and the Allies to stabilize the political situation, Italy was still deeply divided. Many communist partisans had simply refused to lay down their weapons, forming various paramilitary groups hostile to the government, and some right-wing political groups still wanted to restore the old fascist regime.

Scelba's flaw that worsened the situation to the point of no return was the very reason he was appointed head of the DC: his staunch opposition to communism. The young Prime Minister was apparently obsessed with the idea that the PCI and its allies represented a serious threat to Italy.

For this reason, Scelba had tried to exclude the PCI from the first National Liberation Committee, and had expelled Togliatti's party from the government in 1946.

His paranoia, however, only increased after the expulsion of Palmiro Togliatti and other leftist politicians. The outbreak of civil wars in China and Greece convinced the Prime Minister that all leftist parties had as their sole objective the overthrow of the established order and the creation of a dictatorship similar to the fascist one.

In Scelba's eyes, every single problem that that afflicted Italy was Togliatti's fault. Strikes by workers in the industrial regions and by peasants in the South, the formation of neo-fascist groups, and even the economic problems of the First Republic were part of the communist plan to discredit his government.

For this reason, Scelba sought to strengthen security inside the Italian republic. Under his rule, not only were the funds and the number of recruits destined for the police force increased, but many suspected communists and socialists were also dismissed outright from political institutions and the army.

Scelba's anti-communist paranoia was so strong that between 1947 and 1948 the Prime Minister prevented any investigation into the attacks by criminal groups against strikers and trade unionists active in South Italy. Scelba probably had no connection to these attacks, but he feared that admitting the political reasons behind these acts of violence would have increased the popularity of the PCI.

Paradoxically, it was precisely the measures adopted by Scelba that weakened his government and strengthened his political opponents. Scelba's inability or refusal to stop the violence against trade unionists and peasants in the South seriously compromised the popularity of the DC, to such an extent that some areas of southern Italy abandoned the party in favor of the PCI, the PSI or the new Front National of Giorgio Almirante and Alfredo Covelli.

Many of the expelled soldiers became part of the various left-wing or right-wing paramilitary groups, active in the peninsula after the war. The open hostility of the government against anyone considered a leftist subversive also prompted Pietro Nenni and Giuseppe Saragat to ally with Togliatti to form the Fronte Nazionale Popolare (Popular Democratic Front).

Not only did Scelba's paranoia unite all of his left-wing opponents, but it also irreversibly divided the DC. In 1947, Giovanni Gronchi and a fairly large number of parliamentarians abandoned the DC to found Democrazia Popolare (Popular Democracy), stating that Scelba’s anti-comunist obsession was destroying the legacy of De Gasperi.

Internal tension reached its peak during the 1948 election. Togliatti and his allies were convinced that Scelba wanted to kill them, the Prime Minister feared that the Vatican too had been infiltrated by the communists, and Almirante accused both groups of being dangerous spies in the employ of Moscow and/or Washington.

The poll results were of particular concern to Scelba. While the DC was still the leading party in the South, much of Central and Northern Italy had started to prefer the DP and the FNP. Worse, even in South Italy the DC was losing precious votes to the neo-fascists/monarchists of the FN.

Even if the exact number could not be calculated, the DC was in danger of losing a large number of parliamentary seats after the election. In Scelba's eyes, the risk of an electoral victory of the National Popular Front was high.

In the end, Scelba's fears were not realized, as the DC remained the leading party in Italy. Unfortunately, Scelba also discovered that his party no longer had the number of seats in the Senate and Chamber needed to govern.

Indeed, none of the parties had won the number of seats required for the formation of a government. Less than two years after the birth of the First Republic, Italy was facing its first constitutional crisis.

Almost as a prelude to the subsequent conflict, the period between April and June 1948 is commonly known as "The Months of Lead", due to the massive violence that engulfed Italian cities.

In these two months, Italy found itself without a government, while Scelba and Togliatti both tried to convince the DP, now the third party in Italy, to ally with the DC or the FNP. At the same time, supporters of the DC and the FNP clashed with each other and with the police in the streets of the peninsula.

In the end, Togliatti became both the latest casualty of the Months of Lead and the first victim of the new civil war. On 14 July 1948 Antonio Pallante, a supporter of the overthrown monarchy, shot and killed the leader of the PCI.

How this assassination led to the outbreak of a new civil war depends on which version of events one decides to believe. According to the PCI and its allies, Togliatti's body was still warm as Scelba imposed martial law and ordered the arrest of the FNP leadership.

On the contrary, Scelba's supporters claim that the leaders of the FNP had already fled to Bologna well before Scelba knew of Togliatti's death. According to this version, Scelba would have imposed a state of emergency only because the FNP had declared war on his government, after forming the Second National Liberation Committee.

In any case, the Second Civil War became inevitable on July 4, 1948, when the troops stationed in Emilia Romagna refused orders from Rome, and swore allegiance to the government of Bologna.

In some ways, it is striking how the conflict in Italy mirrored in many aspects the civil wars in China and Greece. In all three cases, the Nationalist government was soon forced to retreat in the face of the advancing Communists/Socialists, due to its internal divisions and poor training of its troops.

The DP's decision to join the FNP in January 1949 determined the victory of Bologna. After this event, the main industrial cities of Northern Italy, including Milan, Trieste and Venice, fell into the hands of the SCLN.

Despite the huge economic and military aid from NATO, Scelba's troops thus ended up clashing with a better armed and organized army.

Rome was abandoned by Scelba and his government on 23 May 1951 and Naples, the last capital of the First Republic in mainland Italy, fell after three days of intense fighting on 10 September of the following year.

Scelba was ,however, far from any fight at the time. The Prime Minister had loaded what was left of his government onto a plane bound for his native Sicily two days before the start of the siege.

Since most of the Italian fleet had sunk or sided with his government, Scelba counted on turning Sicily and Sardinia into safe havens from which to plan an eventual reconquest of mainland Italy.

Scelba's latest plan was only half successful: although the two islands still host the government of the First Italian Republic, Scelba never arrived in Sicily.

Indeed, his plane exploded somewhere over the Strait of Messina about an hour after takeoff, killing all the passengers. It is still unclear whether it was a simple accident or whether Scelba was killed by his enemies or former allies.

In any case, his death had no particular consequences on the conclusion of the civil war. Even if Bologna had no way to invade Sicily and Sardinia, the military government, that had suceeded Scelba, could not in any way reverse the tide of the conflict.

Thanks to the mediation of the Yugoslav and French governments, a sort of ceasefire was signed by both sides in early 1953. As in China and Greece, the country's mainland came under the total control of the communist forces and their allies. Instead, the government that had opposed them had to take refuge on an island, under the constant protection of NATO.

Although neither Bologna nor Cagliari were willing to diplomatically recognize each other's rule, both were forced to accept this new status quo as they could not continue fighting.

Thus began a new era of the history of Italy.

Last edited: