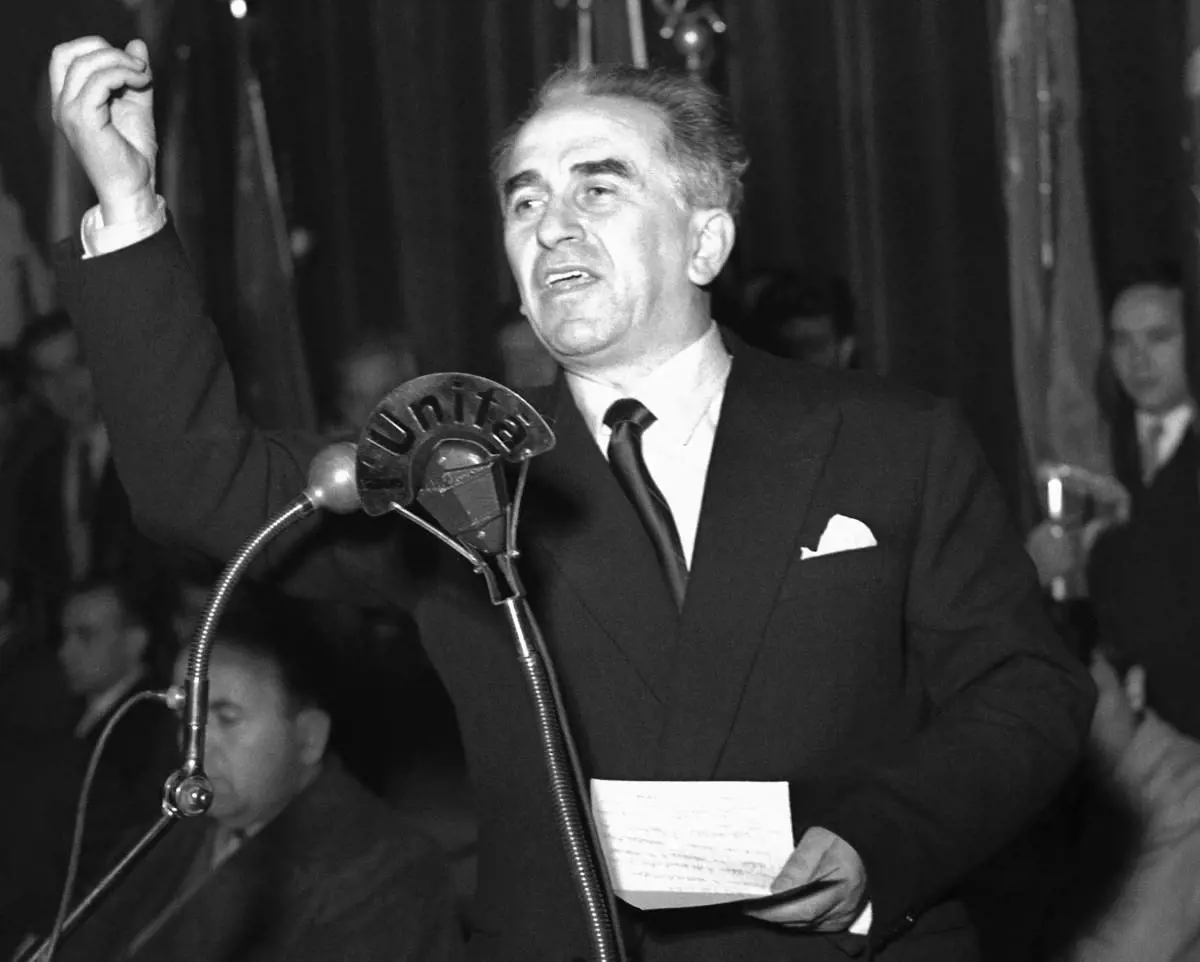

GIUSEPPE DI VITTORIO

The Trade Unionist

According to legend, Beria was executed in 1949 because Stalin was convinced that the NKVD file on Giuseppe Di Vittorio had been falsified. Although this story is clearly false, it confirms in any case the atypicity of Di Vittorio compared to the other members of the PCI.

To begin with, Di Vittorio did not come from a working-class family in the North, but from a family of Apulian labourers. Despite being one of the founding members of the PCI, De Vittorio also did not share Togliatti's admiration for Stalin at all.

During the fascist dictatorship, in fact, Di Vittorio had refused to follow Togliatti and the rest of the PCI in exile in Moscow, preferring to stay in Paris. During his stay in France, Di Vittorio had proposed for the first time the creation of a common front between the socialists and the communists, breaking away from the official position of the Comintern.

Di Vittorio's political rise began thanks to the Nazi invasion of France. In 1941, Vicky authorities arrested the Italian exile and deported him to Italy, where he was sentenced to more than twenty years in prison for his opposition to the fascist regime and support for Republicans during the Spanish Civil War.

Barely three years later, the fascist regime had been overthrown, Di Vittorio was free and the First Civil War had begun. The new conflict thus led to the rebirth of the CGIL in 1944, when Di Vittorio persuaded the communist, socialist and Catholic trade unionists to create a common front against the Salo regime.

Paradoxically, the return of democracy in Italy made Vittorio even more combative and distrustful of the government in Rome. Elected parliamentarian in 1946, Di Vittorio became famous for his frequent interventions in Parliament against Scelba's anti-leftist rhetoric, and his apparent indifference to the violence and poverty in South Italy.

The chaos of those years greatly increased Di Vittorio's political influence. The CGIL became the largest trade union in Italy, responsible for the numerous strikes that blocked the peninsula between 1946 and 1948.

Di Vittorio's real fortune was being in Bologna during the assassination of Togliatti. When the news of the death of the PCI leader spread, his collaborators and other FNP leaders were more concerned with escaping from Rome than reacting to what happened.

Unlike them, Di Vittorio was safe in the city, which many considered the inofficial capital of Italian communism. On the evening of June 14, 1948, the communist channels of the Italian radio started broadcasting Di Vittorio’s first speech in favor of the armed insurrection against Scelba.

When Saragat, Pietro Secchia and the other members of the FNP arrived in Bologna a few days later, Di Vittorio had already established the Second National Liberation Committee, and appointed the first commanders of the new Italian People's Army. At that point, his election as the new leader of the FNP was inevitable.

According to Italian propaganda, his skills as a mediator were fundamental in securing the victory of Bologna. It was Di Vittorio who persuaded the DP to side with the SCLN, and the contacts of the CGIL allowed the various armed insurrections, which conquered much of Northern Italy between 1949 and 1950.

On September 10, 1952, what remained of the army of the First Republic either surrendered, or hurried to flee to Sicily and Sardinia. After four years of war, most of the EPI and Central Italy were loyal more to Di Vittorio than to the rest of the FNP.

Di Vittorio was then the new leader of mainland Italy. It was not a particularly enviable position at that time.

The new conflict had devastated Italy once again, destroying most of its cities, and many areas in the South were controlled by gangs of brigands. Rome was also isolated internationally, as President MacArthur and other Western leaders refused to open any diplomatic contact with the new Italian government.

In addition, many of Di Vittorio's old allies were turning against him. Many of them had learned what had happened in those years in Czechoslovakia, where the communist government had purged many of its old allies.

The socialist and DP militias had stopped collaborating with Bologna, and were ready to start a third civil war if necessary.

There was in fact strong pressure from the Soviets and the more extreme members of the PCI on Di Vittorio to get rid of “the internal enemies of the revolution”. But the leader of the CGIL surprised many, agreeing to meet the other leaders of the FNP in neutral Venice, to discuss the future of Italy.

Di Vittorio, in fact, had noticed that, in addition to the Socialists and other Czechoslovak political opponents, the Soviets had eliminated any communist, not completely loyal to Moscow. If accepting a compromise with the rest of the FNP was going to save him from becoming a Russian puppet or dying under mysterious circumstances, Di Vittorio was ready to cut a deal.

The Historic Compromise of February 13, 1953 laid the foundations of the Second Italian Republic. Di Vittorio and his cabinet (now called the Politburo) were recognized as the highest political authority, but all initiatives of the new Prime Minister had to be approved by Parliament.

The model of the CGIL was then applied to the whole of mainland Italy: the socialists and the communists divided among themselves the control of the new institutions and the government of the various Italian regions. The first action of the new Parliament was to vote unanimously for the ban and dissolution of the DC in the new state.

Despite the particular political structure and seemingly neutral name, it quickly became clear that the Second Republic was a communist country. The first Plan of the Five Years envisaged, in fact, the almost total abolition of private property in mainland Italy.

The factories and agricultural fields in each Italian region came under the control of the Regional Councils for Economic Development, whose members were chosen by the governor of the region but answered directly to the Minister of Economy.

Di Vittorio also concentrated the economy of the Second Republic towards the industrialization and reclamation of many Italian territories. Convinced that Italy should have been as independent as possible, the new Prime Minister's Five-Year Plan focused mainly on certain sectors, such as wheat cultivation and weapons production.

The CGIL became an unofficial government organization. The other trade unions were banned, and every worker in Italy had to register with the CGIL if they hoped to advance their careers.

On the other hand, the Second Republic was notable for its ambiguous and difficoult relationship with the Kremlin. Di Martino distrusted the Soviets, but mainland Italy desperately needed economic aid.

Italy's fate improved in April 1953 when Stalin, finally proving ha had an heart, died from a stroke. Nikolai Bulganin, eager to consolidate his new position of General Secretary as quickly as possible, agreed to help Rome only in exchange for the opening of Italian ports to the Soviet fleet, rather than Rome's accession to the Stalingrad Alliance.

And of course the Second Republic agreed to unquestionably follow Moscow’s foreign policy. Between 1953 and 1956, Italian propaganda completely adopted both the Kremlin's anti-Western and anti-American rhetoric, and Moscow's official line regarding the purges against Bulganin's political rivals.

For this reason, Di Vittorio made a single trip outside mainland Italy during his rule. In 1955, the Prime Minister traveled to Israel, as Bulganin believed that the visit would further strengthen the new alliance between Moscow and Tel Aviv.

However, relations between Moscow and Rome fell into crisis in 1956, following the Soviet suppression of the Bulgarian Uprising. While many communist newspapers in Europe and the rest of the world praised the Soviet military intervention, L'Unità supported in part the cause of the rioters.

Even if the Italian newspaper did not support the anti-communist cause of the Bulgarian rebels, the anonymous author of the article nevertheless denounced Georgi Dimitrov's incompetence and corruption as the main cause of the uprising. In addition, Moscow’s armed intervention was criticized as contrary to Marx’s ideals, and detrimental to the stability of European communist regimes.

Although hardly anyone read that article outside the Second Republic, the Soviet ambassador to Italy immediately requested a meeting with the Prime Minister. Neither the Soviets nor the Second Republic have any records of the conversation between Di Vittorio and the ambassador, but it certainly had no positive outcome.

A few days later, Moscow suddenly announced that interest rates for loans to the Second Republic had been raised.

Worse still, the Kremlin reminded the ambassador of the Second Republic that many Italian soldiers, who had participated in the invasion of Russia in 1941, were still prisoners in the Siberian gulags. Although the Kremlin had agreed to have them repatriated, the agreement could be interrupted at any time.

The 1956 diplomatic crisis was eventually won by Moscow. L’Unità retracted the article, and Enzo Tortora, its possible author, was fired.

However, the disproportionate Soviet reaction had important consequences for the domestic policy of the Second Republic. Suddenly, a large part of the population of the peninsula shared Di Vittorio’s distrust of Moscow.

In the last year of his government, Di Vittorio began purging various Stalinists and other pro-Soviet communists from the government, and began to take an interest in foreign policy, starting to send weapons to the forces of Hossein Fatemi during the Iranian Civil War.

Di Vittorio’s last political action was the signing of the Treaty of Eternal Friendship with the Republic of San Martino on 9 September 1957, recognising the independence of the city state in exchange for its continued neutrality.

Obviously the effects of the treaty were insignificant, but Italian propaganda still claims that it demonstrated Rome’s complete independence from Moscow.

Perhaps for this reason, many conspiracy theorists believe that Di Vittorio did not die of a heart attack, but was poisoned by Moscow two months after the signing of the treaty. Obviously these conspiracy theories tend to ignore that Di Vittorio had long suffered from heart problems, and that his designated successor was even more anti-Soviet than he was.

Di Vittorio is still a controversial figure both in continental Italy and abroad. His admirers praised his conduct before and after the Second Civil War, particularly his decision to preserve Italian democracy, and his social reforms, such as the legalization of abortion and divorce.

His detractors, on the contrary, consider him a common dictator. The foundation of the Ministry of Ideological Integrity caused the arrest and exclusion of many politicians and ordinary citizens, accused of having collaborated with Scelba or simply having sympathies for "capitalist fascism". In fact, it is not possible to justify in any way the arrest of Gronchi, the suspected death of Saragat, or the decades-long exclusion of the DP from the political life of Mainland Italy.

Many, moreover, point precisely to Di Vittorio’s economic and social policies as the cause of the violence and misfortunes that struck the Second Republic in the following decade, including the tragic end of his successor.

In any case, Di Vittorio is still considered one of the most important figures of the twentieth century, whose face decorates posters and T-shirts around the world.