Capture of Cavite

As soon as news reached the southern provinces of Batangas, Cavite, Laguna[1] and Tayabas[2] of the capture of Manila to the army of a criollo captain, immediately various groups of people, especially those turned, often forced to banditry or those who defy friar ownership of their lands took the time to do their bidding. So much so that 3 days after the fall of Tondo, only major towns, often in the coast, or those heavily populated in the interior were left out of bandit-controlled territory. In Tayabas's case however, the residents formed a free government, since most land in Tayabas was natively owned, and only few belonged to the friars. Seizures of friar and allied principalia lands became common. Those who refused to cede were often lynched or murdered by peasants. Some parts of Bulacan[3] were also affected by bandits.

This was the case in the province of Cavite, where it was considered a center of banditry ever since the Spanish first set foot on Luzon. Since the 1770s onward banditry in the province had achieved a rate that was never seen before in other bandit-infested provinces such as Bulacan and Tayabas. The most prominent of these bandit groups was the one led by Luis de los Santos, well known by his nickname, Luis Parang or El Tulisan, which instilled terror on the Spanish due to his timely attack while waiting for the enemy to arrive, hence the nickname

Parang, which came from

para, meaning

to park.

Parang was leading a peasant rebellion against the Spanish back in 1822 when he took word that Novales, a captain of the Spanish army in Manila, rebelled and took over the capital. He ignored this news, although it captured his interest as nobody except the Brits had even captured Manila. Later, he now expressed a desire to form an alliance with Novales after the entire province of Tondo fell to the rebels in a matter of days.

Since the only parts of Cavite remaining under Spanish control are the municipalities of the Cavite peninsula[4] and Cavite Viejo[5], northern Bacoor as well as small pockets of villages loyal to the Spanish, Parang sent one of his accomplices, Juan Upay to Manila for the purpose of forging an alliance between the two sides, arriving at June 14. This reception generated mixed reactions, who distrusted bandits due to the destruction they caused. However, upon the arrival of the Novales brothers (Calba was stationed in Tambobong on Mariano's orders to defend northern Tondo from Spanish attacks) on June 15, they let them in, due to them knowing that most bandits were forced to their current status due to oppression. Andres had no time to met the Caviteño as he traveled around Tondo to recruit troops for the cause.

Upay, Mariano and some of the principalia playing panguingue while discussing an alliance at the Palacio del Gobernador

Initially, Upay only considered forging an alliance at the behest of Parang, but instead Mariano gave him another offer: he, Parang and other major bandit leaders shall be inducted into the soon to be established Imperial Army to trained as regular officers, while their followers would be irregulars. However, Mariano warned them of the consequences if they attempted to loot, kill and persecute, even friars. This was something that Upay disagreed, but he had no other choice but to comply. He doesn't want the rebel government to been seen as brutes.

Along with over 500 troops, and equipment given to Upay by Mariano, he departed Manila by June 18, and reached Parang's camp two days later. Upay explained to Parang what Mariano told him, as well as a plan for a joint attack against the Spanish holding in the northern regions. He also told the bandit leader that they shall be inducted into the army, in which most of them agreed. Parang however chose to be the

alcalde mayor (governor) of Cavite instead.

With all things set aside, they marched from their camp at Imus[6], to the outskirts of Cavite Viejo and Bacoor on June 19, still dawn, arriving by 9am in the morning. A contingent of troops sent by Mariano, numbered 200 marched from Las Piñas to join Parang's forces. While marching towards the capital, the townsfolk had mixed reactions: some welcomed them as liberators, while others closed their doors. Nevertheless, they took over friar and principalia estates, becoming state property, with some being distributed to the peasants.

Once they reached the outskirts of Dalahican[7], the Spanish tried to fend them off with cannonfire, in the hopes that their positions shall be liquidated. However, due to most of the soldiers defending the peninsula were mostly Indios, they often defy, or simply ignore any orders of their superiors. Even worse was some defected to the rebels, giving vital information about the area.

A Spanish captain overseeing the defense fortifications at southern Dalahican

The rebels decided to just encamp around the area while they themselves do marching and combat drills, at the same time sending some troops to retaliate for their previous bombings. This lasted for 3 days, and Parang decided to lure the Spanish by making a false retreat back to Cavite Viejo. Carrying all of their equipment and supply trains, they made such a move on June 23. The Spanish fell for the ruse, and the captain ordered a mobilization of his forces and to attack the retreating rebels, which later found themselves surrounded on all sides: north and south by rebel troops thanks to quick mobility of the army and east and west by sea. As a result the Spanish took heavy casualties and losses of equipment, and most of them became POWs. Those who managed to escape attempted to return, but news broke out that most of their Indio men had mutinied and took over Cavite Nuevo, causing them to surrender in droves.

The fall of Cavite reached the capital on June 25, and all of the bandit leaders were rewarded and retired. Some chose to become local chief of the cuadilleros in several barrios and towns. Parang was subsequently promoted to a general, but true to his word, he refused. Instead he took the position of alcalde mayor, and most Spanish officers were detained in Fort Santiago. Subsequent with the liberation of Cavite was the creation of the

Asemblea de Cavite, the first, although localized form of an independent Philippine institution, followed by an assembly in Tondo.

Laguna and Batangas campaigns

After the fall of Cavite, the rebel leaders set their eyes on the province of Laguna. After resting for a while, they prepared their forces numbering about 2,000, and set foot on July 11 led by Juan Balat, a Lagueño who was also a bandit who joined Parang.

From Muntinlupa, they took San Pedro Tunasan[8] without a fight, and advanced towards Biñan, where they found out that the entire municipality led by a defector of the principales, Juan Monica Mercado welcomed the rebels, and even allocated the local forces to the rebels. Mercado, despite being a respected figure among the Spanish, still nevertheless had some feuds with the friars about his hacienda. He saw the rebel movement as a tool to get rid of the friars, as well as seeing his native Laguna being ran by the Indios, both in the government and church alike.

Mercado himself joined the rebels under the ambitions of becoming the alcalde mayor of Laguna, which directly led him in conflict with Balat's own ambitions to become the alcalde mayor instead. Nevertheless, they put all of their differences and continued their march across the province.

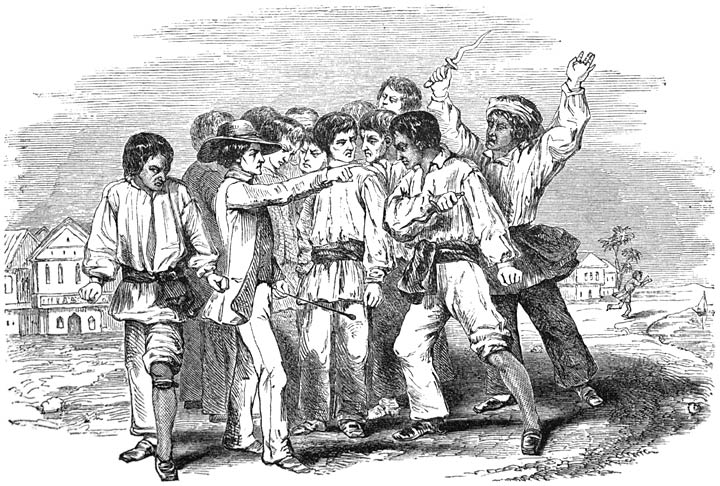

A voluntary irregular in Laguna who joined the rebel army

During their march across Laguna, defection of prominent principales was rampant, while peasants raided several friar lands.

The Spanish there finally decided to stop the advance once and met at Calauan at July 18, where they were soundly defeated by the better trained, and somewhat equipped rebel army of bandits-turned soldiers, irregulars and regulars in a series of skirmishes around the grasslands of the municipality. From there, they retreated back to Pila[9], the last municipality before Pagsanjan, the provincial capital. As a result, the Spanish fiercely defended the municipality, but due to several occasions of Indio soldiers defying orders, Pila fell on July 24, the same day of the battle. Afterwards, Mercado and Balat entered Pagsanjan, and celebrated by doing a victory march on its plaza.

The fall of Pagsanjan to the rebels caused the entirety of the province south of Paete[10] to surrender within rebel hands. Friars were often imprisoned, some escaped to the mountains and became monks, while the principalia faced harassment of lands, and some cases of lynching and mob attacks. Bandits in the province then surrendered and went back to their normal lives before they were forced into banditry.

However, there were still some form of resistance up north of Paete, which was quickly subjugated by Balat, and a force from Andres, which unknowingly sent a force to assist the campaign at Laguna due to the belief that they were battling with the Spanish down south.

By July 28 all of Laguna was under rebel hands, after Infanta[11] surrendered without a fight the previous day.

Simultaneous with the campaign in Laguna was another campaign in Batangas, led by Upay. Unlike in Laguna were there were large bandit activity but checked by Spanish forces occasionally, Upay entered Batangas with ease, in just 3 days from July 11 to 14. Balayan[12] surrendered by July 17 after a 3-day siege.

The battle of Mt. Macolod, on eastern Balayan began on July 18, just a day after the fall of Balayan proper to the rebels. The battle was famous for the first use of the

Cuerpos Arqueros, an elite unit established by Upay himself, which was composed of the most skilled archers, but also riflemen who used handmade-guns found in the rural parts of Katagalugan. Since there are only few musketeers and granadiers stationed in the Philippines at this time, archers were still a major part of the local force, even though musketry has been expanded by the Spanish starting in the 18th century. The Cuerpos wore the first standardized uniform of any Philippine force excluding the Napoleonic-style uniforms of the Spanish army in the Philippines, characterized by wearing a long-sleeve baro, a long salaual, salacot with a red outline, and wide, red handkerchief on the shoulders.

Cuerpos Arqueros (bow illustration supposed to be much wider and larger lol)

With these famed archers, combined with some well-trained regulars from former Spanish army regiments, the rebels managed to destroy the ill, panicked and disarray Spanish and its loyalists, beginning the fall of Batangas. After the battle, few skirmishes were exchanged at the outskirts of Batangas town on July 21, before the capital surrendered since it didn't want to suffer a long siege. As a result of this battle, along with the integration of free Tayabas into the empire, the rebels controlled much of the Tagalog heartland, and set the stage for the war to expand beyond it. Some coastal villages and some of the mountainous interior were taken by Spanish loyalist who continued to plague the rebels' control.

The dispute regarding the position of alcalde mayor of Laguna arrived at Manila on July 23, in which Andres suggested a compromise: Balat shall be the

maestro de campo (commander of the province) while Mercado shall be the alcalde mayor, until elections were held in the near future. Upay was immediately named alcalde mayor of Batangas, where as the position of alcalde mayor of Tayabas remained vacant.

[1] - Territory from the 1790s until 1856 included Rizal east of Cainta and Taytay and the northern and southern parts of the Quezon municipalities of Real and Mauban

[2] - Territory before 1902 consisted merely of southern Quezon, renamed in 1946

[3] - Territory until 1848 included Valenzuela (Polo until 1960) and excluded San Miguel (ceded 1848) and DRT(?)

[4] - Divided into smaller municipalities until 1903

[5] - Now Kawit (as of 1901), included much of Noveleta except the northern part until 1868

[6] - Included Dasmariñas until 1867 (separated as Perez Dasmariñas, reannexed in 1903, separated and renamed in 1917)

[7] - Former muncipality which currently comprises of northern Noveleta and southern Cavite City

[8] - Now San Pedro (as of 1914), included before 1907 the Muntinlupa barangay of Tunasan (Tunasancillo until 1907)

[9] - Included Victoria (Nanhaya until separated) until 1949

[10] - Included Pakil (Paquil before the early 20th century) until 1676 and Kalayaan (separated as Longos) until 1909

[11] - Included General Nakar until 1949 and Real until 1960

[12] - Included Calaca until 1835, Tuy until 1866 (reannexed in 1903 and separated in 1911), Calatagan until 1912 and Lian until 1915 (itself included Nasugbu until 1947(?))