I have to say this thread is a work of art. My hats off to you sir! You have kept me entertained when I should be working for the last few weeks with your daily updates. You should be proud and are sure to receive a turtledove for your efforts.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Dead Live: A Hundred Years' War Timeline

- Thread starter Zulfurium

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 50 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Update Forty-Three: Regnum Balticum Update Forty-Four: Bloody Horror Update Forty-Five: A Bloody Climax Update Forty-Six: The Splintered Realm Update Forty-Seven: The Eastern War Update Forty-Eight: Urbane Heresy Update Forty-Nine: Strife in Iberia Update Fifty: King's End

Update Nineteen: A Hero's Return

This is one of the shortest updates I have had so far, but I really needed to get all the different actors back into place in preparation for the next couple of updates. The updates that come after this one are very long and really get into particularly England and France during and after the Crusade.

As news of the Battles of Sveshtniy first arrived in Europe, the populace was first gripped by shock and horror at the defeat and massacre of French and German knighthood. The victory which followed this tragedy heightened the joy that the following victory brought. Bells were rung across Europe in celebration of the victory, which Bayezid was cursed to the darkest reaches of hell. The news that followed in the next couple of years of victory upon victory and the driving of the Turks from Europe resulted in immense celebrations. On learning of the Fall of Edirne and the following treaty with Süleyman, Pope Honorius V ordered that celebratory masses be held and that the names of the fallen martyrs be published far and wide with prayers ordered said for them for a year - a luxury rarely bestowed on those not able to pay for the privilege. Pope Honorius found himself exalted by European Christendom (1). He used this newfound prestige to institute reforms and restructuring of several religious orders in an effort to streamline and ensure compliance with the dictates of Rome. Using his part of the bounty from the crusade, Honorius set up various facilities to aid the poor and needy in Rome's vicinity. Food was soon distributed and shelters provided while the city found itself experiencing a profound degree of growth, bringing with it artists, composers and writers to raise Rome's status back to the heights it had once held (2).

In the meantime, the crusaders slowly made their way home, returning through Bulgaria - where Ivan Sratsimir feasted them and handed out titles and honors as thanks for their service in saving Bulgaria from the depredations of the Turks. In his train, Edward brought with him the venerable Georgios Gemistos Pletho who he had invited to visit his Kingdom and teach at the University of Oxford for a while, an offer only accepted due to Pletho's regard for Edward and interest in tutoring the young John Lydgate. Pletho would return to Constantinople in 1403 and would become a central part of the Eastern Roman Court. Continuing onward to the Danube, the crusaders returned the way they had come. Arriving at Buda, Sigismund hosted the crusaders for half a year, once more heaping honors and titles on them - and taking the opportunity to offer lands in Croatia to select younger sons to ensure a loyal base of support in the region. Sigismund and Edward spent a long time together, pursuing their shared interests in literature, hunts and martial pursuits (3). A Grand Tournament was held to celebrate the victorious crusade in October 1398 with both crusaders and knights from across Central Europe and Italy turning up for the festivities. In the following Tourney, fought between English, French, German and Hungarian teams the Hungarians were able to emerge victorious, to great celebration and acclaim of the local populace. Sigismund was able to use the presence of the crusaders to force the recalcitrant Hungarian nobility to perform homage at the Grand Tournament to himself, his wife and his son Charles, and was able to end the last remnants of opposition to their rule over Hungary (4).

Wenceslaus IV, King of Bohemia

Once the snows cleared, the crusaders resumed their march homeward along the Danube. In Vienna many of the German contingents peeled off, returning to their homes with great fanfare. Wenceslaus of Bohemia had been King of the Romans since 1376, but on his father Charles's death in 1378, Wenceslaus inherited the Crown of Bohemia and as Emperor-elect assumed the government of the Holy Roman Empire. The problem lay in Wenceslaus lack of a papal coronation, the result of widespread conflict in Germany and Bohemia throughout his reign. In 1387 a quarrel between Frederick, Duke of Bavaria, and the cities of the Swabian League allied with the Archbishop of Salzburg gave the signal for a general war in Swabia, in which the cities, weakened by their isolation, mutual jealousies and internal conflicts, were defeated by the forces of Eberhard II, Count of Württemberg, at Döffingen, near Gafenau, on 24 August 1388. The cities were taken severely and devastated. Most of them quietly acquiesced when King Wenceslaus proclaimed an ambivalent arrangement at Cheb in 1389 that prohibited all leagues between cities, while confirming their political autonomy. This settlement provided a modicum of stability for the next many years, however the cities dropped out as a basis of the central Imperial authority in this period(5).

Even in Bohemia Wenceslaus held a tenuous grip on power at best, as he came into repeated conflicts with the Bohemian nobility led by the House of Rosenberg. On two occasions he was even imprisoned for lengthy spells by rebellious nobles. But the greatest liability for Wenceslaus proved to be his own family. Charles IV had divided his holdings among his sons and other relatives. Although Wenceslaus upon his father's death retained Bohemia, his younger half-brother Sigismund inherited Brandenburg, while John received the newly established Duchy of Görlitz in Upper Lusatia. The March of Moravia was divided between his cousins Jobst and Procopius, and his uncle Wenceslaus I was made Duke of Luxembourg. Hence the young king was left without the resources his father had enjoyed. In 1386, Sigismund became king of Hungary and became involved in affairs further east. Wenceslaus also faced serious opposition from the Bohemian nobles and even from his chancellor, the Prague archbishop Jan of Jenštejn. In a conflict surrounding the investiture of the abbot of Kladruby, the torture and murder of the archbishop's vicar-general John of Nepomuk by royal officials in 1393 sparked a noble rebellion. In 1394 Wenceslaus' cousin Jobst of Moravia was named regent, while Wenceslaus was arrested at Králův Dvůr. King Sigismund of Hungary arranged a truce in 1396, and for his efforts was recognized as heir to Wenceslaus (6).

In view of his troubles in Bohemia, Wenceslaus did not seek a coronation ceremony as Holy Roman Emperor and was long absent from the German lands. Consequently, he faced anger at the Reichstag diets of Nuremberg in 1397 and Frankfurt in 1398. The four Rhenish electors, Count Palatine Rupert III and the Archbishops of Mainz, Cologne and Trier, accused him of failing to maintain the public peace. They demanded that Wenceslaus appear before them to answer to the charges in June 1400. Wenceslaus demurred, in large part because of renewed hostilities in Bohemia. When he failed to appear, the electors meeting at Lahneck Castle declared him deposed on 20 August 1400 on account of "futility, idleness, negligence and ignobility". The next day they chose Rupert as their king at Rhens, though Wenceslaus refused to acknowledge this successor and hoped to crush this revolt against his rule (7).

The crusaders re-entered France in August 1399. They were received at the gates of Dijon with acclamation and gifts of silver presented by the municipality. In Paris the King gave his cousin, Jean Sans Peur, a gift of 20,000 livres. The towns of Burgundy and Flanders vied for the honor of receiving him. On orders of his father, he made a triumphal progress to exhibit himself to the people whose taxes had bought his return. Minstrels preceded him through the gates, fetes and parades greeted him, more gifts of silver and of wine and fish were presented (8). While news of the First Battle of Sveshtniy brought quieter memorials and bitter disappointment, with much blame heaped on the traitorous English and Hungarians - sometimes adding the Burgundians depending on their political persuasions, the majority of the realm's efforts were spent on celebrating a victorious crusade (9). By the end of the celebrations it had become increasingly clear that Enguerrand VII de Coucy's wife Isabelle de Coucy was pregnant - a seeming miracle for the almost 60-year old lord who was without a male heir (10). Edward V found himself in an ambiguous position with many of the French, who admired his role as leader of the crusade but hated him for the First Battle of Sveshtniy and his Englishness. The English contingent left Digenois and marched for Flanders, arriving in Bruges in late September 1399, to further celebrations before setting sail for England.

Procession through London's Streets Celebrating The Turkish Crusade

King Edward V's return to England was an event celebrated across the realm, his arrival brought with it profound hope and joy to the people of the English realm. The return of their pious king from the crusade which they had heard glowing reports of for years was an event like no other. The streets of London were decorated at immense expense and the Parliament was assembled to vote through honors to the returning crusaders. David Stewart, who was heir to the Scottish throne, returned as a twenty-year old veteran crusader heaped with honors by half the courts of Europe and was betrothed to the four-year old Mary of England in preparation for his return to Scotland where he hoped to remove his uncle from power and ensure his own succession to the throne. Edward quickly found himself drawn into the near anarchic conditions that had emerged under his brother's regency, learning with horror of how wrong everything had gone(11).

Footnotes:

(1) Honorius is in a really good position at this point. His election ended the hated schism, he just presided over a successful crusade and is ruling from Rome. His political capital is at a high point at this point in time.

(2) Honorius is beginning his reforms slowly while trying to ensure that his local support is firmed up. Rome is in a much better place than OTL, and is undergoing something like the resurgence it would later in the 15th century IOTL. The beginnings of the Rennaissance are starting to emerge now, somewhat earlier than OTL due to the greater stability of Europe as a whole.

(3) Sigismund is a really fascinating ruler who had the capacity for greatness, but never really reached the heights he could have due to his shifting and uncertain powerbase. Things look much better for him this time around.

(4) IOTL Sigismund returned from the Battle of Nicopolis with his tail between his legs. His authority and prestige at a low point. He experienced further revolts and rebellions, experiencing capture and humiliation. This time he returns with the might of a successful crusading army, his succession secured and his wife as a strong source of legitimacy.

(5) Wenceslaus really didn't have the capacity to rule the HRE at this point in time and was in a much weaker position than his father to begin with.

(6) Wenceslaus really had a hard time of things, probably not helped by his rampant alcoholism. This is all OTL.

(7) I don't have a strong enough grasp of HRE history to know if something like this had been done before - but this is OTL. We are going to get into this entire conflict much more in a later update.

(8) Weirdly enough this was all OTL. When the crusaders returned from Nicopolis, having spent several years imprisoned, they were feasted and feted, with lots of celebrations and festivities. I thought it would be a good base point to work from with the celebrations.

(9) Edward fills this weird place in French consciousness, he is a successful and prolific king who has done well by his subjects and has led a successful crusade, but at the same time he is their greatest enemy and he has brought incredible suffering to their lands. They respect his achievements, but hate him for it.

(10) I couldn't let the Coucy dynasty die out at this point. Their fate IOTL is just so sad and disappointing, with Philippa de Coucy being a repudiated wife while Marie de Coucy found herself fighting for her inheritance while her family died around her and Isabelle de Coucy, née Bar seems to have genuinely grieved the loss of her much older husband and had to fight for her right to the lands. The dispute over the Coucy inheritance went on for years while it was picked apart by the avaricious royal dukes.

(11) We will learn much more about Richard's time as regent in the next update. Things really didn't work out too well.

A Hero's Return

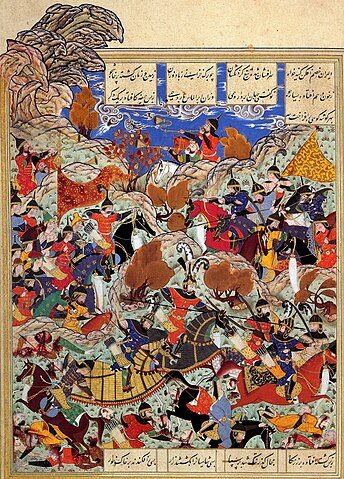

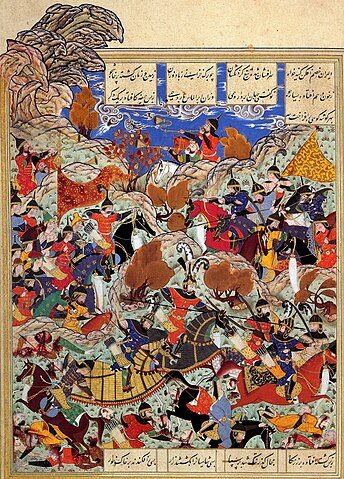

Depiction of the Victorious Crusaders

Depiction of the Victorious Crusaders

As news of the Battles of Sveshtniy first arrived in Europe, the populace was first gripped by shock and horror at the defeat and massacre of French and German knighthood. The victory which followed this tragedy heightened the joy that the following victory brought. Bells were rung across Europe in celebration of the victory, which Bayezid was cursed to the darkest reaches of hell. The news that followed in the next couple of years of victory upon victory and the driving of the Turks from Europe resulted in immense celebrations. On learning of the Fall of Edirne and the following treaty with Süleyman, Pope Honorius V ordered that celebratory masses be held and that the names of the fallen martyrs be published far and wide with prayers ordered said for them for a year - a luxury rarely bestowed on those not able to pay for the privilege. Pope Honorius found himself exalted by European Christendom (1). He used this newfound prestige to institute reforms and restructuring of several religious orders in an effort to streamline and ensure compliance with the dictates of Rome. Using his part of the bounty from the crusade, Honorius set up various facilities to aid the poor and needy in Rome's vicinity. Food was soon distributed and shelters provided while the city found itself experiencing a profound degree of growth, bringing with it artists, composers and writers to raise Rome's status back to the heights it had once held (2).

In the meantime, the crusaders slowly made their way home, returning through Bulgaria - where Ivan Sratsimir feasted them and handed out titles and honors as thanks for their service in saving Bulgaria from the depredations of the Turks. In his train, Edward brought with him the venerable Georgios Gemistos Pletho who he had invited to visit his Kingdom and teach at the University of Oxford for a while, an offer only accepted due to Pletho's regard for Edward and interest in tutoring the young John Lydgate. Pletho would return to Constantinople in 1403 and would become a central part of the Eastern Roman Court. Continuing onward to the Danube, the crusaders returned the way they had come. Arriving at Buda, Sigismund hosted the crusaders for half a year, once more heaping honors and titles on them - and taking the opportunity to offer lands in Croatia to select younger sons to ensure a loyal base of support in the region. Sigismund and Edward spent a long time together, pursuing their shared interests in literature, hunts and martial pursuits (3). A Grand Tournament was held to celebrate the victorious crusade in October 1398 with both crusaders and knights from across Central Europe and Italy turning up for the festivities. In the following Tourney, fought between English, French, German and Hungarian teams the Hungarians were able to emerge victorious, to great celebration and acclaim of the local populace. Sigismund was able to use the presence of the crusaders to force the recalcitrant Hungarian nobility to perform homage at the Grand Tournament to himself, his wife and his son Charles, and was able to end the last remnants of opposition to their rule over Hungary (4).

Wenceslaus IV, King of Bohemia

Even in Bohemia Wenceslaus held a tenuous grip on power at best, as he came into repeated conflicts with the Bohemian nobility led by the House of Rosenberg. On two occasions he was even imprisoned for lengthy spells by rebellious nobles. But the greatest liability for Wenceslaus proved to be his own family. Charles IV had divided his holdings among his sons and other relatives. Although Wenceslaus upon his father's death retained Bohemia, his younger half-brother Sigismund inherited Brandenburg, while John received the newly established Duchy of Görlitz in Upper Lusatia. The March of Moravia was divided between his cousins Jobst and Procopius, and his uncle Wenceslaus I was made Duke of Luxembourg. Hence the young king was left without the resources his father had enjoyed. In 1386, Sigismund became king of Hungary and became involved in affairs further east. Wenceslaus also faced serious opposition from the Bohemian nobles and even from his chancellor, the Prague archbishop Jan of Jenštejn. In a conflict surrounding the investiture of the abbot of Kladruby, the torture and murder of the archbishop's vicar-general John of Nepomuk by royal officials in 1393 sparked a noble rebellion. In 1394 Wenceslaus' cousin Jobst of Moravia was named regent, while Wenceslaus was arrested at Králův Dvůr. King Sigismund of Hungary arranged a truce in 1396, and for his efforts was recognized as heir to Wenceslaus (6).

In view of his troubles in Bohemia, Wenceslaus did not seek a coronation ceremony as Holy Roman Emperor and was long absent from the German lands. Consequently, he faced anger at the Reichstag diets of Nuremberg in 1397 and Frankfurt in 1398. The four Rhenish electors, Count Palatine Rupert III and the Archbishops of Mainz, Cologne and Trier, accused him of failing to maintain the public peace. They demanded that Wenceslaus appear before them to answer to the charges in June 1400. Wenceslaus demurred, in large part because of renewed hostilities in Bohemia. When he failed to appear, the electors meeting at Lahneck Castle declared him deposed on 20 August 1400 on account of "futility, idleness, negligence and ignobility". The next day they chose Rupert as their king at Rhens, though Wenceslaus refused to acknowledge this successor and hoped to crush this revolt against his rule (7).

The crusaders re-entered France in August 1399. They were received at the gates of Dijon with acclamation and gifts of silver presented by the municipality. In Paris the King gave his cousin, Jean Sans Peur, a gift of 20,000 livres. The towns of Burgundy and Flanders vied for the honor of receiving him. On orders of his father, he made a triumphal progress to exhibit himself to the people whose taxes had bought his return. Minstrels preceded him through the gates, fetes and parades greeted him, more gifts of silver and of wine and fish were presented (8). While news of the First Battle of Sveshtniy brought quieter memorials and bitter disappointment, with much blame heaped on the traitorous English and Hungarians - sometimes adding the Burgundians depending on their political persuasions, the majority of the realm's efforts were spent on celebrating a victorious crusade (9). By the end of the celebrations it had become increasingly clear that Enguerrand VII de Coucy's wife Isabelle de Coucy was pregnant - a seeming miracle for the almost 60-year old lord who was without a male heir (10). Edward V found himself in an ambiguous position with many of the French, who admired his role as leader of the crusade but hated him for the First Battle of Sveshtniy and his Englishness. The English contingent left Digenois and marched for Flanders, arriving in Bruges in late September 1399, to further celebrations before setting sail for England.

Procession through London's Streets Celebrating The Turkish Crusade

King Edward V's return to England was an event celebrated across the realm, his arrival brought with it profound hope and joy to the people of the English realm. The return of their pious king from the crusade which they had heard glowing reports of for years was an event like no other. The streets of London were decorated at immense expense and the Parliament was assembled to vote through honors to the returning crusaders. David Stewart, who was heir to the Scottish throne, returned as a twenty-year old veteran crusader heaped with honors by half the courts of Europe and was betrothed to the four-year old Mary of England in preparation for his return to Scotland where he hoped to remove his uncle from power and ensure his own succession to the throne. Edward quickly found himself drawn into the near anarchic conditions that had emerged under his brother's regency, learning with horror of how wrong everything had gone(11).

Footnotes:

(1) Honorius is in a really good position at this point. His election ended the hated schism, he just presided over a successful crusade and is ruling from Rome. His political capital is at a high point at this point in time.

(2) Honorius is beginning his reforms slowly while trying to ensure that his local support is firmed up. Rome is in a much better place than OTL, and is undergoing something like the resurgence it would later in the 15th century IOTL. The beginnings of the Rennaissance are starting to emerge now, somewhat earlier than OTL due to the greater stability of Europe as a whole.

(3) Sigismund is a really fascinating ruler who had the capacity for greatness, but never really reached the heights he could have due to his shifting and uncertain powerbase. Things look much better for him this time around.

(4) IOTL Sigismund returned from the Battle of Nicopolis with his tail between his legs. His authority and prestige at a low point. He experienced further revolts and rebellions, experiencing capture and humiliation. This time he returns with the might of a successful crusading army, his succession secured and his wife as a strong source of legitimacy.

(5) Wenceslaus really didn't have the capacity to rule the HRE at this point in time and was in a much weaker position than his father to begin with.

(6) Wenceslaus really had a hard time of things, probably not helped by his rampant alcoholism. This is all OTL.

(7) I don't have a strong enough grasp of HRE history to know if something like this had been done before - but this is OTL. We are going to get into this entire conflict much more in a later update.

(8) Weirdly enough this was all OTL. When the crusaders returned from Nicopolis, having spent several years imprisoned, they were feasted and feted, with lots of celebrations and festivities. I thought it would be a good base point to work from with the celebrations.

(9) Edward fills this weird place in French consciousness, he is a successful and prolific king who has done well by his subjects and has led a successful crusade, but at the same time he is their greatest enemy and he has brought incredible suffering to their lands. They respect his achievements, but hate him for it.

(10) I couldn't let the Coucy dynasty die out at this point. Their fate IOTL is just so sad and disappointing, with Philippa de Coucy being a repudiated wife while Marie de Coucy found herself fighting for her inheritance while her family died around her and Isabelle de Coucy, née Bar seems to have genuinely grieved the loss of her much older husband and had to fight for her right to the lands. The dispute over the Coucy inheritance went on for years while it was picked apart by the avaricious royal dukes.

(11) We will learn much more about Richard's time as regent in the next update. Things really didn't work out too well.

Update Twenty: The Inner Turmoil

This is the first in a series of enormous updates which cover everything from England and France to China and inbetween. There are a lot of new characters introduced in this one, while we say goodbye to others. I really hope you enjoy them, this is one of my favorite updates so far.

Richard's Regency proved a time of lawlessness and license in which feuds reignited and tyranny blossomed. Richard began by placing his supporters in positions of power. Michael de la Pole (1), whose father had helped finance English wars following the fall of the Bardi and Perruzzi banks, had long held a position of power in the treasury and was pushed to take the position of Chancellor of the Exchequer by Richard while Edward of Norwich became Lord Chancellor. Richard worked hard to push against the intransigence of his uncle the Duke of Gloucester who criticized Richard's actions. Robert de Vere, the Earl of Oxford and childhood rival of King Edward found himself suddenly elevated out of obscurity to Lord Warden of Cinque Ports while his efforts at litigating against his uncle Aubrey de Vere suddenly turned fruitful with the full support of the regent to back him, while Richard richly rewarded Robert for his friendship with lands and titles. Joan of Navarre attempted to calm the situation and tried to push Richard into a more conciliatory position, hoping to take on a care-taker role rather than ruling in the interests of his favorites. Richard married a daughter to Jean V de Montfort, Duke of Brittany during this time, and another to Edward of Norwich. Another daughter would marry Thomas de Montagu, son and heir to the Earl of Salisbury.

As the pressure rose within England and those who had found themselves powerless under Edward rose to the highest positions in government, tempers flared and feuds reemerged. In the mid 1380s John de Holland, Regent and King's half-brother by Joan of Kent, had killed Ralph Stafford, son and heir of the Earl of Stafford, over John's previous murder of one of Ralph's archers (2). Edward had come down hard on his half-brother and confiscated many of his lands, even sending him into exile for a while (3). His return in late 1396 at Richard's invitation, soon after Edward had left, and the public welcome by Richard that followed caused an uproar among the Staffords. Richard restored John de Holland to his lands and considered bringing him into the government as Constable of the Tower. This was too much for the Staffords and their ally Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, whose daughter was married to the Earl of Stafford, Thomas Stafford. While John de Holland was making his way home from a long night of drinking and whoring in London, he was set upon by a band of assassins who butchered John de Holland in a frenzied bloodlust (4). When Holland's body was discovered the next morning it provoked an outraged response from the regent, who immediately ordered the imprisonment of Thomas, Duke of Gloucester and the Stafford brothers, Thomas, William and Edmund under suspicion of murder. Knowing they would not get justice from the enraged Richard, the Staffords scattered into the countryside. The Hollands were quick to react, with the dying Thomas de Holland, brother to the murdered John de Holland, forcing his children to swear an oath of vengeance. The Hollands were soon chasing Stafford supporters and murdering them if they could get their hands on them with the tacit approval of the regent. The Duke of Gloucester was able to force his own release by leveraging his connections to Joan of Navarre and the Duke of Clarence and set about trying to protect his son-in-law and his family. Prince Edward found himself increasingly pushed from the council of state and grew increasingly worried for the safety of his mother and siblings, eventually taking the entire royal family to Wales, where he had spent much of his childhood and had established a deep fount of trust and loyalty in the populace (5). The skirmishes and ambushes launched by Staffords and Hollands against each other developed into a shadow war between the regent and his uncle for control of the regency. The conflict would escalate over the next couple of years, and see William Stafford killed in the fighting alongside John and Edmund de Holland, leaving only Thomas de Holland, Third Earl of Kent from among the male half of the de Holland clan while Thomas Stafford, Third Earl of Stafford and his brother Edmund remained of the Stafford male brood by the time of Edward V's return to England (6).

It was in this environment in early 1398 that Thomas de Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk returned to London from his long-time appointment as Lord Warden of the Scottish Marches. On his arrival he found his wife, Philippa, a distressed and hounded woman. Since Robert de Vere had risen to importance he had used any and every opportunity to harass his one-time betrothed in an effort to take out the hatred he had developed for her and family for their betrayal of him in their childhood. Robert had once been set for high office and a near-royal marriage to Philippa. When that collapsed, following a childish fight with King Edward, and his friends turned on him he grew bitter, his fights with his uncle Aubrey de Vere for the return of his lands turned that bitterness into hatred. The moment he had the opportunity to act on his hatred he did (7). With neither the King nor her Husband present in the capital, Philippa had been forced to accommodate the vicious Robert and accept his abuse when the regent turned down her appeals for it to end. Richard had always felt that his friend Robert was much too harshly treated over a childhood brawl, and that the accusations against him were simply a continuation of the abuse heaped on his friend in the past. This emboldened Robert who took what advantages he could, stalking Philippa and her daughters through the Tower of London where they resided following Robert's promotion to Constable of the Tower. Thomas de Mowbray returned to learn that his second eldest daughter, Mary de Mowbray, had only just escaped rape at the hands of Robert de Vere, saved by the intervention of her young brother Ingleram. In a rage, Thomas de Mowbray hunted through the tower in search of Robert and, on finding him, attacked the man. In the following fight Robert de Vere was able to call for support from the guards of the Tower, who were loyal to him, and proceeded to murder the Duke of Norfolk in a cold rage (8). On realizing how far he had gone, Robert abandoned the Tower and fled for the countryside and safety among his supporters. The discovery of Thomas de Mowbray's body in the office of the Constable of the Tower was a scandal fit to shake the foundations of the realm. The devastated Philippa de Mowbray collapsed completely in grief and horror, while the thirteen-year old son and heir to the Duke of Norfolk, Thomas de Mowbray swore vengeance on the murderer of his father and tormenter of his family (9).

While these two feuds occupied the attentions of the realm, Richard grew ever more autocratic. He found himself trapped in a conflict with the Earl of Arundel and his brother, the Archbishop of Canterbury. This struggle, alongside his feud with the Duke of Gloucester and the aftermath of the murder of the Duke of Norfolk, proved too much for Richard. When information shared by Richard's secretary revealed that Richard was planning to launch a major purge of the upper nobility, it was Richard who found himself pushed from power - his position as regent subjected to a council of great lords led by the Duke of Gloucester until the return of King Edward. The powerlessness of his position led Richard to focus more on his informal conflicts, supporting the efforts of the Hollands in trying to defeat and capture the Staffords - who suddenly found themselves with governmental support, while helping Robert de Vere escape to safety in France and plotting vengeance (10).

The End of Richard's Regency

King Edward returned in the midst of this turmoil and was immediately besieged by the different factions, who all blamed each other for the country's woes. The Dukes of Gloucester and Carlisle were at each other's throats from the moment they were called before the King, shouting recriminations and insults. Unable to ascertain anything beyond the utter catastrophe of Richard's Regency and the murder of Edward's half-brother John de Holland and close friend Thomas de Mowbray, he was left fumbling for answers. Witnessing the devastation of his beloved mistress, Philippa de Mowbray, and the flinty-eyed anger of her children - Edward had Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, tried for the murder of the Duke of Norfolk, attainted him, confiscated his lands and sentenced him to death in absentia (11). The young Thomas de Mowbray and his family were the beneficiaries of the lands, with particularly the young Ingleram de Mowbray benefiting - being elevated to Earl of Oxford as reward for his defense of his sister and, as some whispered, a positioning of the king's bastard in a position of power (12). The Stafford-Holland feud proved more difficult to solve, with no clear proof available as to who murdered John de Holland and plenty of illegal actions on either side. As a result King Edward forced the two sides to end their fighting under threat of sanction and attaintment if that proved unsuccessful. At the same time, he forced the marriage of Edmund Stafford to Joan Holland, the widow of Edmund of Langley, Duke of Cambridge, while Thomas de Holland was forced to marry Katherine Stafford. By joining the two lines to each other by marriage, Edward hoped to ensure that the two clans would become too entangled to feud without breaking many of the rules of chivalry and breaking bonds of loyalty held sacred by feudal society(13).

The Dukes of Carlisle and Gloucester would both receive sanctions for their unbecoming behavior during the Regency. Carlisle found himself ordered to take up the position of Lord Warden of the Western Marches, effectively exiling him from the center of power and placing him under Henry Percy, who had just been elevated to Duke of Northumberland for his services in the crusade, who was placed as Lord Warden of the Scottish Marches, while Ralph Neville became Lord Warden of the Eastern Marches under Percy as well (14). A marriage between the Duke of Northumberland's son Henry and the last remaining daughter of the Duke of Carlisle was also arranged. Thomas, Duke of Gloucester was made regent for Edward over Aquitaine (15). This move left the two main combatants of the feud at opposite ends of the English realm and would hopefully keep them too busy to feud with each other. The only problem with this move turned out to be that Richard was not far enough removed from power. He would stew in his anger and humiliation, blaming Gloucester for his fall from power and the chaos of his time as regent, while slowly growing to hate his brother who continually dismissed him and kept him from power. Richard would begin reaching out to those disappointed with Edward's reign, those who found themselves pushed from the halls of power, and would slowly rebuild the support he enjoyed among the disaffected nobility of England (16). Prince Edward would return to London with the rest of the royal family on learning of his father's return and would increasingly spend his time between Wales, where he was learning to govern as Prince, and London where he participated in his father's council of government.

The return of King Edward brought with it a series of changes to the lands and titles. Edward of Norwich was confirmed in his father's titles as Duke of Cambridge while, as has been mentioned, Henry Percy saw his Earldom raised to a Dukedom while the young Thomas de Mowbray inherited his father's title of Duke of Norfolk. John de Grailly, the Earl of Bedford, who had served first as page and later squire to the King found himself knighted and made Knight of the Garter and member of the Order of the Dragon - an arrangement which had been agreed to by Sigismund and Jean de Nevers at Buda, where the Earl had won both the squire's joust and melee. At the same time Edward started looking for matches for his younger sons, Richard of Kent being betrothed to Anne de Mortimer, eldest daughter of Roger Mortimer the heir to the Dukedom of Clarence, and John of Lincoln being betrothed to Isabella de Mowbray, second eldest daughter of the Mowbray family and half-sister to Edward's bastard children by Philippa de Mowbray. The Mowbray family would join the royal family, to an even greater degree than previously, with Edward seemingly acting as patriarch to the family (17). In the meantime Edward restored many of his men to the positions of the cabinet, but allowed the final Constable of the Tower appointed by his brother, John de la Pole - a younger brother of the Earl of Suffolk - to remain in his post (18).

Charles the Child, Dauphin of Viennois

Alone among the major states of late medieval Europe France had a tax administration capable of appropriating much of the surplus wealth generated by France’s economy to the needs of the Crown without any formal process of consent on behalf of taxpayers. The system dated from the 1360s when a number of financial reforms had been introduced in order to pay the ransom of Charles VI’s grandfather Jean II and to suppress the Great Companies which were then operating under English patronage throughout the country. It was founded on the two principal indirect taxes of the French Monarchy: the aides, a sales tax levied at 5 per cent on most commodities exposed for sale and at 8.3 per cent on wine; and the gabelle, an excise on salt, generally levied at a rate of 10 per cent. During the reign of Charles V these impositions had depended, at least in theory, on the consent of various regional assemblies representing taxpayers. But when, in the crisis which followed Charles V’s death in 1379, it proved impossible to obtain consent to their continuance, the government imposed them by decree and brutally suppressed attempts at concerted opposition. From 1382 the aides and the gabelle were supplemented by a new tax, the taille. Tailles were direct taxes imposed on local communities at unpredictable intervals in order to meet financial emergencies, generally connected with war. There was never any pretense of consent to the taille. Between them the aides and the gabelle raised about two million livres in the average year in addition to the revenues of the royal demesne and the yield of the ‘tenths’ levied on the Church. In the first five years of its existence, between 1382 and 1387, the taille added on average another million livres annually. This represented a heavier burden of taxation than any other European state had been able to impose, both in absolute terms and relative to the country’s wealth and population. The war with England provided the political justification for taxation on this scale and the main reason why, in spite of significant discontent and some localised outbreaks of rebellion, it was tolerated by much of the population for a time. But when the war was suspended in 1383 and was followed by the Second Jacquerie, it was allowed to continue unabated, as war expenditure fell to its lowest levels in half a century by 1387. The aides and the gabelle continued onwards after this, albeit at a reduced rate. The taille was initially abandoned but then revived in 1396 and again in 1397. This created a substantial structural surplus of government revenues over the ordinary demands of peacetime government. Yet from about 1399 onward the treasury was insolvent. The King’s receivers and treasurers were meeting his liabilities with bills of assignment payable three years ahead, many of which were dishonored when the time came (19).

The main reason for the insolvency was that government’s revenues were being appropriated on a large scale by the royal princes and their clients, and by the higher reaches of the civil service. In the first two decades of the fifteenth century the situation deteriorated as a bitter struggle for control of the Crown’s resources was fought out in the council chambers of the royal palaces, in the national and regional assemblies, among the consuls and magistrates of the towns and ultimately on the streets. The essential problem was the incapacity of the King. Charles VI had never had his father’s intelligence or strength of purpose, even in his brief prime at the end of the 1380s. But when his mental health collapsed on the march towards Brittany in the early 1390s things took a turn for the worse. For the next many decades of his long reign the French King lived a life of intermittent sanity, interrupted by ever longer and more frequent ‘absences’, the delicate euphemism used to describe the periods when the King would wander through the corridors of his palaces howling and screaming, tearing and soiling his clothes, breaking the furniture or throwing it on the fire, not knowing who or what he was and unable to recognize his closest friends and kinsmen or even his wife, at times he became convinced he was made of glass, and had to be wrapped tightly and protected from harm for fear he would break. In his intervals of lucidity Charles was capable of picking up traces of his previous political positions. He was gracious and could be articulate, even forceful. He acted out his role. He retained the loyalty and affection of his subjects. But he was no longer capable of governing his realm. Politically he was a spent force, content to allow the factions around him to fight their battles over his head as if he were no more than a distant spectator. The situation was too uncertain to warrant a formal regency, which might have provided a measure of continuity and conserved the strength of the Valois monarchy. So while the King lived everything had to be done in his name. Major decisions were deferred until he recovered his faculties. If a decision could not be put off it was taken in his absence but invariably submitted to him later for his confirmation. Charles was at once indispensable and useless. The day-to-day business of government devolved upon the royal council, a protean body comprising the royal princes, the officers of state, a number of bishops active in the work of government, and a shifting cast of prominent magnates and courtiers. The council became the forum for the rivalries and jealousies of faction as power was uneasily contested between the King’s closest relatives, supported by cliques with no real legitimacy in law or security in fact (20).

The French never contemplated deposing the King, even at the lowest ebb of Charles VI’s fortunes. After three centuries in which the power of the Crown had progressively increased, France had come to identify itself more than any other European society with its monarchy. So far as its ancient and disparate provinces had a sense of common identity, it was the monarchy which had created it. So far as it enjoyed effective government, internal peace and security from its enemies, it owed these things mainly to the monarchy. Almost all of its national myths and symbols were centered upon the monarchy. At the end of the fourteenth century the Provençal jurist Honoré Bonet contrasted the cohesion of his adoptive country with the divided societies all around it. France was ‘the column of Christendom, of nobility and virtue, of well-being, riches and faith’, but, he added, ‘above all else she has a powerful King’. The kings of France were supported by an impressive corps of professional counselors, judges and administrators. But the functioning of the state was never wholly impersonal. It remained critically dependent upon the personality of the monarch. The king was not only a ceremonial figure, a symbol of power, the fount of justice, the source of all secular authority. His was the only authority which could resolve the inevitable political differences among his councilors and ministers. Only he could confer legitimacy on controversial decisions of the state: the making of peace and war, the resolution of the prolonged schism of the Church, major dispositions of the royal demesne, the imposition of tailles or the marriage of his children. Above all the king was the indispensable arbiter in the continual contest for royal favor and largesse among the princes and the top officials and churchmen, the jobbery that served as the grease of every European state. If the king could not perform this function himself it was likely to be taken out of his hands by self-interested groups intent on satisfying their own claims and excluding competitors. The traditional analogy between the state and the human body, which likened the king to the head and mind of the body politic, was more than an arresting metaphor. As Bonet had attributed the prosperity of France in the 1390s to the strength of the Crown, so the next generation of moralists would blame its weakness for social disintegration and civil war that they saw all around them. ‘All is now corrupted, all bent on evil work,’ sang Eustache Deschamps, the poet of a deserted court and a dispirited aristocracy; ‘these are the symptoms of monarchy’s decay.’ (20)

The decline of the Crown and the dispersal of power to the nobility and the civil service would have been plain to anyone who wandered among the courts and gardens of the Hôtel Saint-Pol. The King’s business was still carried on there. But the crowds of provincial officials, ambassadors, petitioners, tradesmen and merrymakers, the display and extravagance, the music, laughter and feasting of the King’s youth had all faded away. Charles himself lived surrounded by a meagre court, accompanied by a dwindling band of loyal retainers and servants of low status. One of these wrote in 1406 a pathetic, perhaps exaggerated account of a King, shuffling unshod though his private apartments, without robes to wear in public, horses to ride out with, or even candles to light his bedroom, his manners mocked and patronized, his authority ignored or manipulated by his former courtiers. The great came before him in search of favors at the first sign of recovery, bustling his loyal attendants out of the way and then turned their backs as soon as he relapsed. When the King was ‘absent’ the greedy, the needy and the ambitious looked for opportunities elsewhere, in the halls of the princely mansions of the capital and the anterooms of prominent bureaucrats. In the two decades which followed the onset of the King’s illness, the Dukes of Berry’s daily household expenditure rose threefold, and the daily consumption of meat substantially exceeded the royal court’s. According to the house biographer of the Duke of Bourbon, those who still called at the Hôtel Saint-Pol found no one to receive them and promptly left. ‘Let us go and dine at the mansion of the Duke of Bourbon,’ they would say; ‘we are sure to find a good welcome there.’ (20)

When it became clear that Charles would not be permanently cured, indeed might not even survive, Isabeau had been given her own household and council. They were eventually installed in the Hôtel Barbette, an imposing mansion beneath the old walls of Philip Augustus a short distance north of the Hôtel St-Pol. She was granted an allowance from the treasury for her children and control of her own dower. She received frequent and increasingly generous grants of money, jewelry and land. By 1406 her income had risen to over 140,000 livres a year, a fourfold increase in twelve years. Isabeau forged a close bond with her elder brother, Louis of Bavaria, an astute and covetous professional courtier, paladin and ladies’ man who made frequent visits to France and settled there in the early years of the fifteenth century. For nearly twenty years Louis served as Isabeau’s political adviser and her eyes and ears at court, supporting himself on the largesse of the King, the Queen and the young Dauphin. A rich marriage came his way together with barrels of jewelry, large gifts of money, and pensions and stipends estimated at about 30,000 francs a year (20).

It was under these circumstances that the children of Charles VI grew up and became pawns in the games of the nobility. Great hopes had been heaped on the young Dauphin Charles, who many thought would be able to take over for his father when he grew of age and thereby save France from the rule of a madman. These hopes were for naught. As Charles grew from a toddler into a boy and neared the age of ten it became increasingly clear that he was simpleminded, unable to understand complex concepts and given to childish tantrums which only grew worse with age, it becoming increasingly clear that he would need a regency to rule on his behalf (21). The possibility of following a mad king with a simple and unstable one provoked a deep sense of horror in the hearts of many Frenchmen, which the royal dukes were quick to leap on. While Isabella of France had been married off to Prince Edward of Wales and the Dauphin was betrothed to the English Princess Catherine, that left the royal family with four daughters and three sons unmatched (22). The eldest of the remaining daughters, Jeanne, was betrothed to Amadeus VIII of Savoy at the insistence of Jean de Berry, who was Amadeus' grandfather. The next daughter, Marie, was betrothed to Jean de Never's son Phillip and the one after that, Michelle, to the second son of Louis II d'Anjou, King of Naples, René d'Anjou. The final daughter, Catherine, was bitterly fought over by the different factions - with Louis d'Orléans emerging victorious, betrothing Catherine to his son and heir Charles d'Orleans (23). The three sons would become puppets in the intrigues of the princes as they were fought over by the different sides. The eldest of the available princes was Louis, who was swiftly married to Margaret de Bourgogne, while the next prince, Jean, would eventually find himself married to the Navarrese princess Aliénor de Navarre, younger daughter of Pedro of Navarre. The final prince, Phillip, was rumored to be the son of Louis d'Orleans and had his support from the beginning. Phillip would eventually marry a daughter of Louis d'Anjou named Jeanne d'Anjou (24).

The Triumph of Death, Depicting the social upheaval and terror that followed the plague

Nine months after the festivities marking the return of the crusaders ended, Enguerrand VIII de Coucy was born (25). The boy stood to inherit one of the largest estates in France. Stretching from Picardy to the Aargau and with marriage ties from the Kings of Aragon to the Kings of England, the Coucy's were at the center of French politics in the region. Under Enguerrand VII de Coucy their lands had grown to include the County of Soisson, Brisgau, Sundgau, parts of the Aargau and Ferrete, not to mention the Duchy of Benevento in Naples. He had served as advisor and ambassador to Kings and Popes, was a noted Crusader and had close ties of blood to English, Barrios and Lorrainer Dukes. His act of freeing the prisoners at the Battles of Sveshtniy also proved fruitful, with William of Ostrevant arranging the betrothal of his newborn daughter Jacqueline of Bavaria (26) to the young Coucy heir. With no other children at the time, this elevated the young Coucy to unforeseen heights, placing potential control of Hainault, Bavaria-Straubing, Frisia and Holland into his hands once his future father-in-law died. Soon after, in 1403, the elderly Enguerrand VII de Coucy died of the plague sweeping France at the time, leaving the regency to his young wife Isabelle de Lorraine who, while grief-stricken, served very capably with the support of William of Ostrevant.

The Plague that swept through France from 1398 to 1403 was the worst instance to hit the country since the initial outbreak in the middle of the fourteenth century and was by far the longest so far (27). The Plague was present in two forms: one that infected the bloodstream, causing the buboes and internal bleeding, and was spread by contact; and a second, more virulent pneumonic type that infected the lungs and was spread by respiratory infection. The presence of both at once caused high mortality and swift spread of contagion. So lethal was the disease that cases were known of persons going to bed well and dying before they woke, of doctors catching the illness at a bedside and dying before the patient. In a given area the plague accomplished its kill within four to six months and then faded, except in the larger cities, where, rooting into the close-quartered population, it abated during the winter, only to reappear in spring and rage for another six months. This process would repeat for years during this long-lasting outbreak. When graveyards filled up, bodies at Avignon were thrown into the Rhône until mass burial pits were dug for dumping the corpses. In Paris such pits corpses piled up in layers until they overflowed. Everywhere reports came of the sick dying too fast for the living to bury. Corpses were dragged out of homes and left in front of doorways. Morning light revealed new piles of bodies. When the efforts to remove the corpses failed because the tenders had all died, the dead lay putrid in the streets for days at a time. When no coffins were to be had, the bodies were laid on boards, two or three at once, to be carried to graveyards or common pits. Families dumped their own relatives into the pits, or buried them so hastily and thinly “that dogs dragged them forth and devoured their bodies.” Amid accumulating death and fear of contagion, people died without last rites and were buried without prayers from the terrified clergy, a prospect that horrified the last hours of the stricken (28).

Flight was the chief recourse of those who could afford it or arrange it. The rich fled to their country places and settled in pastoral palaces removed on every side from the roads with wells of cool water and vaults of rare wines. The urban poor died in their burrows and only the stench of their bodies informed neighbors of their death. That the poor were more heavily afflicted than the rich was clearly remarked at the time, in the north as in the south. The pest attacked especially the and common people, seldom the magnates. The misery and want and hard lives made the poor more susceptible along with close contact and lack of sanitation. It was noticed too that the young died in greater proportion than the old, though not as many as in some previous occurrences. In the countryside peasants dropped dead on the roads, in the fields, in their houses. Survivors in growing helplessness fell into apathy, leaving ripe wheat uncut and livestock untended. Oxen and asses, sheep and goats, pigs and chickens ran wild and they too, according to local reports, succumbed to the pest. In the Alps wolves came down to prey upon sheep and then, “as if alarmed by some invisible warning, turned and fled back into the wilderness.” In the Auvergne, bolder wolves descended upon a plague-stricken city and attacked human survivors. For want of herdsmen, cattle strayed from place to place and died in hedgerows and ditches. Dogs and cats fell like the rest (28).

In all, a quarter of France's population perished over the course of those five years, with many important figures among the dead. The first to die was Antoine de Bourgogne, who was heir to the Duchy of Brabant and half of the marriage alliance between the Dukes of Burgundy and Berry. He was soon followed by the Duchess of Brabant, the woman he was meant to succeed, resulting in Jean de Nevers becoming Duke of Brabant instead (29). Charles d'Anjou, Prince of Taranto and regent for his brother Louis II in France, died soon afterwards with both of his young sons and his wife - his lands and tasks would be taken up by Louis II d'Anjou's second son René when he grew old enough. Louis II, Duc de Bourbon and his son Louis both died as well (30), while Armand Arnaud d'Albret, the Seigneur of Albret, followed soon after (31). Bonne de Bourgogne and Phillip d'Artois, Count of Eu and Constable of France, died in 1401, leaving their seven-year old son Phillip d'Artois as heir and the Constableship once more unfilled and a bone of contention between the royal Dukes (32). Gaston IV de Foix, the count of Foix and Armagnac, died in 1402 along with his wife Beatrix, leaving two sons and three daughters, the eldest of whom would become Gaston V de Foix under the regency of his now-ancient grandmother Agnès de Navarre. He would marry his cousin Princess Bonne de Navarre, daughter of Pedro of Navarre, soon after - cementing Navarrese control of the Foix-Armagnac lands (33). The last spate of deaths included the ancient giants of French politics. First to die was the ever-hardworking peacemaker Enguerrand VII de Coucy, whose son succeeded him in all of his titles. Next to die was the venerable Jean de Berry, called The Magnificent, Duc de Berry and Royal uncle. The final magnate to die of the 1398-1403 plague was Phillip de Bourgogne, called The Bold, Duc de Bourgogne (34). The two dukes were followed by their respective sons, who had none of the childhood friendships that the old dukes had had with their brothers. The next generation of Dukes had taken their seats at the games of power, and they would not leave the field of battle until they were dead or victorious (35).

Footnotes:

(1) The de la Poles never became Earls of Suffolk ITTL, but they do retain important positions in government. The aforementioned father of Michael de la Pole really did take over the financing of the war in France for Edward III and Richard when the Italian banks broke under the strain. That is how the de la Pole family came to power IOTL, rising from rich merchants to Dukes of Suffolk and marriage partners to royalty in a couple generations. It is rather impressive to be honest.

(2) This is an OTL event. The circumstances surrounding the murder of Ralph Stafford are more uncertain, with much pointing towards John being unaware that he was killing the heir to a powerful earldom at the time.

(3) IOTL Richard sanctioned him heavily, but forced the two sides to reconcile. Edward is harsher with his half-brother, banishing him and taking most of his lands. Whether that works out better than OTL is the question.

(4) Without John de Holland trying to make up for things, and in fact returning despite an order of exile, the Staffords don't have the closure they did IOTL which provokes them to taking this drastic action. This sort of thing wouldn't have happened if Edward was present, but he is half-way across Europe at this point in time.

(5) The fact that the situation has become so tense that the royal family seeks safety in Wales should really be an indicator of how badly things are going. The general lawlessness that is gripping England see many of these feuds erupt into bloodshed, as can be seen from what happened under particularly Henry VI IOTL. Richard doesn't have the power or authority he did IOTL, which makes his attempts at crushing his opposition seem more like a personal vendetta rather than a struggle for royal power.

(6) Things really get quite bloody for a while with the Holland-Stafford feud. Here is to hoping that Edward can bring them to peace.

(7) My treatment of Robert de Vere ITTL really isn't very fair, but I think this is a logical end point for him. With all of the abuse and bitterness from the opposition of several kings, the moment he has the license to do so he acts on it.

(8) The irony of Robert de Vere being obsessed with the woman he repudiated IOTL is rather bitter, but when considering the role she played in his fall from grace I think it fits the narrative quite well and he seems the type given to obsession. The murder of the Duke of Norfolk by the Constable of the Tower is a scandal of epic proportions and really sets things turning against Richard, who has sanctioned so much of Robert's behavior. We also get to meet Ingleram de Mowbray who will come to play a much more important role as we go on.

(9) Oaths of vengeance were really in style at the time. On a more serious note, the Mowbray family is really incredibly traumatized by the entire event.

(10) The power struggle in England isn't quite as well developed as in France, and with a competent monarch is somewhat restrained.

(11) This is similar to the punishment exacted against him IOTL, just far more deserved this time around.

(12) The other de Vere's are not going to be happy about these developments. They just lost their hereditary title and are going to want it back.

(13) Whether this solution actually works is rather questionable, and there are many who expect the entire feud to erupt again at any moment, but for now the threats and ties to each other are enough to hold them in place.

(14) Sending him to fight the Scots is about the only thing Edward can come up with to keep his uncle and brother from fighting with each other publicly. Edward is really in a great deal of difficulty, trying to figure out what actually happened and ends up just trying to either bind everyone together with marriages or push them as far apart as possible.

(15) Thomas has spent plenty of time in France already and has administered large swathes of land before, so ruling Aquitaine should be a good opportunity for him, and keeps him far, far away from Richard.

(16) Richard really isn't pleased with how things turns out, and being punished for his work as regent really sits wrongly with him. This is the start of a dark road for him, which really won't end happily. For anyone.

(17) The Mowbray's were already almost part of the royal family, Thomas' death really brings them fully into the fold and sets them up for great things in the future.

(18) This might not be too great of an idea of Edward's part, but there really isn't any reason to remove John de la Pole at this point in time.

(19) The only changes from OTL here is that the taille is implemented two years before OTL and runs for much longer without military conflict to justify it. This should really help people to understand why the French populace is absolutely furious with the nobility constantly.

(20) This is all OTL. I thought it would be interesting to look at the role of the monarchy in France and how Charles' intermittent madness undermined ordinary rule of France.

(21) We don't know much about this Charles because he died quite young. I thought it would be interesting to look at the dynamics is several of Charles' children survive. I know that this is seeming more and more like a France-Screw, but I really wanted to explore the dynamics of what the nobility would do if faced with yet another incapacitated monarch when there are several healthy younger princes with close ties to the different ducal families. The building blocks for the latter parts of Charles' reign are being placed now.

(22) It is really important to remember that not only is the Dauphin "simple", but he is also the son-in-law of the English King. A father-in-law or wife often ends up functioning as regent in situations like this. The French are not liking the implications of that one bit.

(23) The daughters are spread out among the different ducal families. With several powerful ducal families, more than OTL, the competition for royal brides is even fiercer than IOTL and they therefore all end up married into French families.

(24) Each faction now has a Prince to support. Things are going to be soooo fun…

(25) A Coucy heir is going to have a lot of interesting effects on north-eastern France and the Low Countries.

(26) This is the Jacquline, Countess of Hainault who was part of the reason for the Anglo-Burgundian alliance breaking IOTL. This potentially gives the Coucy's control of some of the most prosperous parts of the Netherlands, and directly challenges the Bougogne and Bavarian claims to dominance in the region.

(27) This Plague also hit IOTL, though I haven't been able to find too much about who died of it specifically. This time there are a lot of important people who are going to be affected. It was one of the worst bouts of Plague in France's history.

(28) This is all based on descriptions of the first Black Death outbreak in 1348-49.

(29) The Duchy of Brabant thereby becomes part of the Bourgogne inheritance far quicker than IOTL.

(30) This is the younger son of Louis de Bourbon, his elder son succeeds him like IOTL.

(31) His son Charles d'Albret was Constable at Agincourt IOTL. The Albrets would at one point reach incredible heights as Kings and Queens of Navarre, before marrying into the Bourbon Family. The child born of the Albret-Bourbon union was the man who eventually became King Henri IV of France and founded the Bourbon dynasty which includes Louis XIII through XVIII. It is also worth noting that this is not the René who became King of Naples IOTL due to the marriage of Joanna II of Naples and Louis II d'Anjou providing a different mother than IOTL.

(32) The Constableship is going to be interesting to witness and the factions are going to become increasingly polarised. This also leaves Jean de Nevers as regent to his young grandson and gives him control of parts of Normandy, flanking Orléans lands in the process.

(33) The Navarrese needed to keep hold of the Foix-Armagnac inheritance, and so they do. Gaston V de Foix is not going to be the non-entity his father was. He has more in common with his OTL Armagnac cousins, his Foix grandfather and Navarrese relations.

(34) The death of Jean de Berry and Phillip de Bourgogne really mark the end of an era. Without them events begin to take on a much darker nature - much as it did IOTL. Their heirs are going to be playing rough.

(35) Without the closeness of growing up together and having lived with the incessant feuding of all their parents, the newest generation of Dukes are not going to back down without a fight. They are going to be willing to go further than their parents to get what they want. I have been really fascinated lately with thoughts of why exactly the royal cadet branches, both in France and England, only started fighting each other for real after the progenitors of the lines passed away. It is Louis d'Orléans and Jean Sans Peur who end up murdered, while the Lancaster and York Kings murdered any and every relation they could get their hands on.

The Inner Turmoil

Richard, Duke of Carlisle as Regent of England

Richard, Duke of Carlisle as Regent of England

Richard's Regency proved a time of lawlessness and license in which feuds reignited and tyranny blossomed. Richard began by placing his supporters in positions of power. Michael de la Pole (1), whose father had helped finance English wars following the fall of the Bardi and Perruzzi banks, had long held a position of power in the treasury and was pushed to take the position of Chancellor of the Exchequer by Richard while Edward of Norwich became Lord Chancellor. Richard worked hard to push against the intransigence of his uncle the Duke of Gloucester who criticized Richard's actions. Robert de Vere, the Earl of Oxford and childhood rival of King Edward found himself suddenly elevated out of obscurity to Lord Warden of Cinque Ports while his efforts at litigating against his uncle Aubrey de Vere suddenly turned fruitful with the full support of the regent to back him, while Richard richly rewarded Robert for his friendship with lands and titles. Joan of Navarre attempted to calm the situation and tried to push Richard into a more conciliatory position, hoping to take on a care-taker role rather than ruling in the interests of his favorites. Richard married a daughter to Jean V de Montfort, Duke of Brittany during this time, and another to Edward of Norwich. Another daughter would marry Thomas de Montagu, son and heir to the Earl of Salisbury.

As the pressure rose within England and those who had found themselves powerless under Edward rose to the highest positions in government, tempers flared and feuds reemerged. In the mid 1380s John de Holland, Regent and King's half-brother by Joan of Kent, had killed Ralph Stafford, son and heir of the Earl of Stafford, over John's previous murder of one of Ralph's archers (2). Edward had come down hard on his half-brother and confiscated many of his lands, even sending him into exile for a while (3). His return in late 1396 at Richard's invitation, soon after Edward had left, and the public welcome by Richard that followed caused an uproar among the Staffords. Richard restored John de Holland to his lands and considered bringing him into the government as Constable of the Tower. This was too much for the Staffords and their ally Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, whose daughter was married to the Earl of Stafford, Thomas Stafford. While John de Holland was making his way home from a long night of drinking and whoring in London, he was set upon by a band of assassins who butchered John de Holland in a frenzied bloodlust (4). When Holland's body was discovered the next morning it provoked an outraged response from the regent, who immediately ordered the imprisonment of Thomas, Duke of Gloucester and the Stafford brothers, Thomas, William and Edmund under suspicion of murder. Knowing they would not get justice from the enraged Richard, the Staffords scattered into the countryside. The Hollands were quick to react, with the dying Thomas de Holland, brother to the murdered John de Holland, forcing his children to swear an oath of vengeance. The Hollands were soon chasing Stafford supporters and murdering them if they could get their hands on them with the tacit approval of the regent. The Duke of Gloucester was able to force his own release by leveraging his connections to Joan of Navarre and the Duke of Clarence and set about trying to protect his son-in-law and his family. Prince Edward found himself increasingly pushed from the council of state and grew increasingly worried for the safety of his mother and siblings, eventually taking the entire royal family to Wales, where he had spent much of his childhood and had established a deep fount of trust and loyalty in the populace (5). The skirmishes and ambushes launched by Staffords and Hollands against each other developed into a shadow war between the regent and his uncle for control of the regency. The conflict would escalate over the next couple of years, and see William Stafford killed in the fighting alongside John and Edmund de Holland, leaving only Thomas de Holland, Third Earl of Kent from among the male half of the de Holland clan while Thomas Stafford, Third Earl of Stafford and his brother Edmund remained of the Stafford male brood by the time of Edward V's return to England (6).

It was in this environment in early 1398 that Thomas de Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk returned to London from his long-time appointment as Lord Warden of the Scottish Marches. On his arrival he found his wife, Philippa, a distressed and hounded woman. Since Robert de Vere had risen to importance he had used any and every opportunity to harass his one-time betrothed in an effort to take out the hatred he had developed for her and family for their betrayal of him in their childhood. Robert had once been set for high office and a near-royal marriage to Philippa. When that collapsed, following a childish fight with King Edward, and his friends turned on him he grew bitter, his fights with his uncle Aubrey de Vere for the return of his lands turned that bitterness into hatred. The moment he had the opportunity to act on his hatred he did (7). With neither the King nor her Husband present in the capital, Philippa had been forced to accommodate the vicious Robert and accept his abuse when the regent turned down her appeals for it to end. Richard had always felt that his friend Robert was much too harshly treated over a childhood brawl, and that the accusations against him were simply a continuation of the abuse heaped on his friend in the past. This emboldened Robert who took what advantages he could, stalking Philippa and her daughters through the Tower of London where they resided following Robert's promotion to Constable of the Tower. Thomas de Mowbray returned to learn that his second eldest daughter, Mary de Mowbray, had only just escaped rape at the hands of Robert de Vere, saved by the intervention of her young brother Ingleram. In a rage, Thomas de Mowbray hunted through the tower in search of Robert and, on finding him, attacked the man. In the following fight Robert de Vere was able to call for support from the guards of the Tower, who were loyal to him, and proceeded to murder the Duke of Norfolk in a cold rage (8). On realizing how far he had gone, Robert abandoned the Tower and fled for the countryside and safety among his supporters. The discovery of Thomas de Mowbray's body in the office of the Constable of the Tower was a scandal fit to shake the foundations of the realm. The devastated Philippa de Mowbray collapsed completely in grief and horror, while the thirteen-year old son and heir to the Duke of Norfolk, Thomas de Mowbray swore vengeance on the murderer of his father and tormenter of his family (9).

While these two feuds occupied the attentions of the realm, Richard grew ever more autocratic. He found himself trapped in a conflict with the Earl of Arundel and his brother, the Archbishop of Canterbury. This struggle, alongside his feud with the Duke of Gloucester and the aftermath of the murder of the Duke of Norfolk, proved too much for Richard. When information shared by Richard's secretary revealed that Richard was planning to launch a major purge of the upper nobility, it was Richard who found himself pushed from power - his position as regent subjected to a council of great lords led by the Duke of Gloucester until the return of King Edward. The powerlessness of his position led Richard to focus more on his informal conflicts, supporting the efforts of the Hollands in trying to defeat and capture the Staffords - who suddenly found themselves with governmental support, while helping Robert de Vere escape to safety in France and plotting vengeance (10).

The End of Richard's Regency

The Dukes of Carlisle and Gloucester would both receive sanctions for their unbecoming behavior during the Regency. Carlisle found himself ordered to take up the position of Lord Warden of the Western Marches, effectively exiling him from the center of power and placing him under Henry Percy, who had just been elevated to Duke of Northumberland for his services in the crusade, who was placed as Lord Warden of the Scottish Marches, while Ralph Neville became Lord Warden of the Eastern Marches under Percy as well (14). A marriage between the Duke of Northumberland's son Henry and the last remaining daughter of the Duke of Carlisle was also arranged. Thomas, Duke of Gloucester was made regent for Edward over Aquitaine (15). This move left the two main combatants of the feud at opposite ends of the English realm and would hopefully keep them too busy to feud with each other. The only problem with this move turned out to be that Richard was not far enough removed from power. He would stew in his anger and humiliation, blaming Gloucester for his fall from power and the chaos of his time as regent, while slowly growing to hate his brother who continually dismissed him and kept him from power. Richard would begin reaching out to those disappointed with Edward's reign, those who found themselves pushed from the halls of power, and would slowly rebuild the support he enjoyed among the disaffected nobility of England (16). Prince Edward would return to London with the rest of the royal family on learning of his father's return and would increasingly spend his time between Wales, where he was learning to govern as Prince, and London where he participated in his father's council of government.

The return of King Edward brought with it a series of changes to the lands and titles. Edward of Norwich was confirmed in his father's titles as Duke of Cambridge while, as has been mentioned, Henry Percy saw his Earldom raised to a Dukedom while the young Thomas de Mowbray inherited his father's title of Duke of Norfolk. John de Grailly, the Earl of Bedford, who had served first as page and later squire to the King found himself knighted and made Knight of the Garter and member of the Order of the Dragon - an arrangement which had been agreed to by Sigismund and Jean de Nevers at Buda, where the Earl had won both the squire's joust and melee. At the same time Edward started looking for matches for his younger sons, Richard of Kent being betrothed to Anne de Mortimer, eldest daughter of Roger Mortimer the heir to the Dukedom of Clarence, and John of Lincoln being betrothed to Isabella de Mowbray, second eldest daughter of the Mowbray family and half-sister to Edward's bastard children by Philippa de Mowbray. The Mowbray family would join the royal family, to an even greater degree than previously, with Edward seemingly acting as patriarch to the family (17). In the meantime Edward restored many of his men to the positions of the cabinet, but allowed the final Constable of the Tower appointed by his brother, John de la Pole - a younger brother of the Earl of Suffolk - to remain in his post (18).

Charles the Child, Dauphin of Viennois