For information about the history of Indonesia, 1950-1970, see:

https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...rnative-cold-war.280530/page-21#post-11164323

Despite Western media representations of the rise of communism in Indonesia/Nusantara as a sudden takeover, it in fact was the result of the gradual breakdown of the tripartite

Nasakom (Nationalism, Religion, Communism) balance that President Sukarno had tried to establish. A major contributing factor to the collapse of Nasakom was that the three pillars of the state were themselves unstable; the generals that comprised the "nationalist" base were often self-serving, scheming and focused on their own enrichment through management of state enterprises than on the wellbeing of their country, their junior officers split by different loyalties and visions of Indonesia's future; the Islamists concerned communists as well as non-Muslim regions like Bali; and the communists, whilst able to find large bases of support, were riven by factionalism. The 30 September Movement finally pushed

Nasakom over the edge; The 30 September Movement was spearheaded by military officers sympathetic to the PKI, and as the fruit of the labours of Kamaruzaman Sjam. Hailing from the northeastern Javan town of Tuban and descended from Arab traders, Sjam had been a member of the

pathuk group of youths which opposed Japanese occupation in Yogyakarta during the Second World War. After the war, he had joined the PKI and maintained a number of contacts from former

pathuk members who were now officers in the Indonesian army. In 1964, Sjam had been appointed head of the top-secret PKI Special Bureau. The Special Bureau's existence was hidden even from PKI Central Committee members and took orders from Aidit himself. Sjam and his small group of subordinates in the Special Bureau infiltrated several military bases (to which they were provided access by old friends of Sjam) and established a degree of trust with certain notable officers by passing on intelligence regarding Islamist rebellions throughout the country. This arrangement of course benefitted the PKI by pitting their two greatest threats, the military and the Islamists, against each other, whilst slowly but surely turning elements of the military onside. In the meanwhile, the PKI also grew increasingly close with Sukarno and the leftist wing of the PNI, with the right wing PNI regional party bosses actually often defying the will of Sukarno whilst local PKI elements supported the unitary policies of the president. By 1968, Sukarno's reliance on the PKI and affiliated groups such as the SOBSI (

Sentral Organisasi Buruh Selurah Indonesia - Central All-Indonesian Workers Organisation) trade union confederation and the

merah milisi was practically complete. Opposition army officers had been crushed by the red militias, loyalist army elements and the air force, whilst the Indonesian Navy (TNI-AL) supported the PKI-PNI government due to their increasing ties with Eastern bloc suppliers and their interests regarding Maluku and West Papua. Isolated on the various islands, the rebellious army officers were forced to surrender piecemeal.

Ceremony held by the Sidang Presidium of SOBRI. Note the portrait of Friedrich Engels

In 1968 Aidit was appointed Vice President, a post that had been vacant since the resignation of Mohammad Hatta in December 1956. Despite this, he was by now the most powerful man in Indonesia. It is a matter of historical controversy to which degree Sukarno fully supported the policies that would be implemented under Aidit's direction; even if he did not, he surely felt he had no other allies left; the Islamists and conservatives opposed him, the United States had sought to overthrow him. The communists were at least willing to keep him alive and nominally in charge of the country. 1969 saw the establishment of a new cabinet, stacked almost entirely with communist leaders. Aside from Aidit, of course, it also included figures such as Siauw Giok Tjhan/Shao Yu'tsan [245], who was made a minister without portfolio but would spend a great deal of time maintaining good relations with Peking; Muhammad Hatta Lukman; Oloan Hutapea as Minister of Culture; Subandrio as Foreign Minister (one of the few non-communists, he had nevertheless been the architect of the

konfrontasi with Malaya and the West); and Sjam as Interior Minister. Sudisman maintained his position as General Secretary of the PKI. Shortly thereafter, Sukarno announced the renaming of Indonesia, which would from then on be known as Revolutionary Nusantara. In virtually all organisations (except those openly opposed to the new government), the name

Nusantara replaced Indonesia. The newly-rebranded Partai Komunis Nusantara (PKN) and their

merah milisi turned their eyes onto their opposition within the left. The smaller internal purge of the PKN included amongst its notable victims Njoto. Njoto had once been a notable figure in the PKI, regularly travelling to the Soviet Union to promote ties between the CPSU and the PKI. Njoto had caused controversy by travelling in the Soviet Union with Rita, an Indonesian student living in Moscow and studying Russian literature. Rita was supposed to translate between Russian and Indonesian for Njoto, but the two ended up having an affair whilst Njoto's wife Soetarni was back in Indonesia, pregnant with their sixth child. A rift had already been growing between Njoto and Aidit, particularly regarding different views on the Sino-Soviet split. The affair was a scandal that the PKI could ill-afford, and it gave Aidit an excuse to oust Njoto from the leadership of the PKI. Sukarno would maintain a good relationship with Njoto however, even unsuccessfully trying to convince him to establish a "People's Party" based on "Sukarnoism". With Sukarno no longer positioned to protect Njoto, he was arrested on espionage charges and was executed on September 16th, 1969.

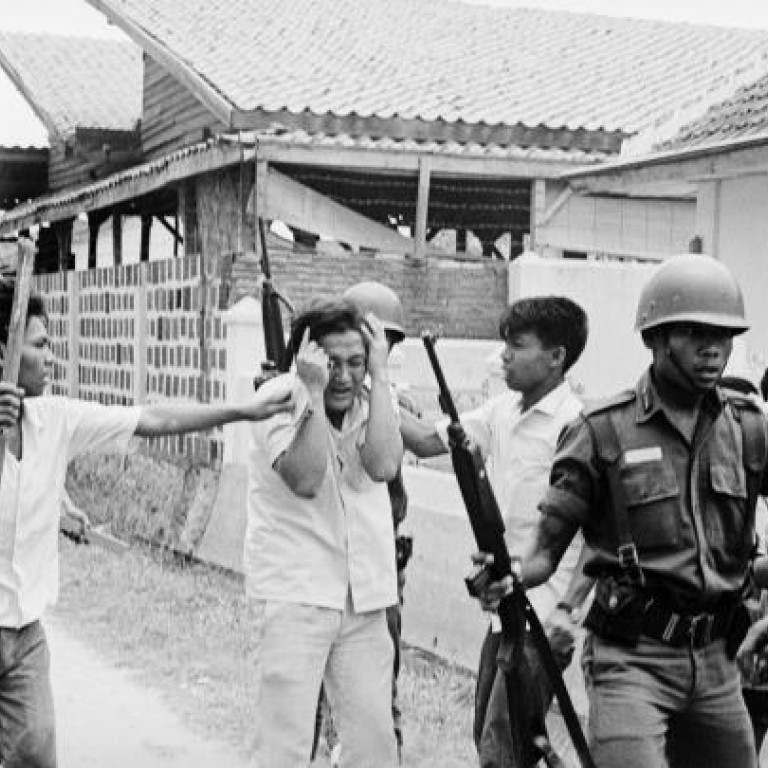

Murba Party member being harassed by local PKI activists and police

The most viciously-suppressed target of the security forces of Revolutionary Nusantara was the

Murba Party. The Murba Party had emerged out of the political vacuum of the late 1940s as the PKI reeled from the aftermath of the Madiun Affair. It was an amalgamation of four main groups: the Revolutionary People's Movement, People's Party, Poor People's Party and the Independent Labour Party of Indonesia and led by their leaders, Tan Malaka, Chairul Saleh, Sukarni and Adam Malik. Guerrilla units loyal to

Murba were active against the Dutch in West and Central Java in the 1950s. The

Murba Party has been characterised as extremely nationalistic, secular and "messianic" in its social radicalism. The group was particularly popular with workers and ex-guerrillas. The leadership of the party were sympathetic to the Soviet Union. Adam Malik himself had been ambassador to the USSR and Poland until his return to Indonesia in 1963 and was appointed trade minister. As the PKI sided with China in their disputes with the Soviets,

Murba intensified their courting of Moscow, hoping to replace the PKI in international socialist organisations, which didn't come to pass. In 1965, at the suggestion of the PKI, Sukarno ordered a number of arrests on

Murba activists, despite appointing Malik as Foreign Minister and even briefly as Deputy Prime Minister. The PKI denounced

Murba as a "Trotskyite" organisation, and as "puppets of imperialists". In 1969-1970, Offices of the

Murba Party were raided by

merah milisi and burnt to the ground. In the progress of arrests, many of these supporters were beaten to death. Others were thrown into prisons throughout Nusantara. Murba was outlawed, along with the

Acoma Party, which had emerged out of the Young Communist Force, led by Ibnu Parna and affiliated with

Murba.

A later image taken in one of the Unity Villages established during the Social Revolutionary period

The Central Committee of the PKN engaged in a rapid programme of social and economic transformation. The immediate effects of these policies was dislocation; a number of localised famines forced the central government to engage in forced requisitioning of rice from farmers. The owners of farming estates were often subjected to violence and collectivisation of their farms, whilst small peasant smallholders also had their rice taken, but were usually left unmolested except in the case of withholding of produce or destruction of surplus; in these instances summary execution was not uncommon. Inherited high levels of inflation were gradually controlled by a major devaluation of the rupiah, although this also wiped out the savings of many Nusantarans. PKI leadership's savings were largely converted and stored in Switzerland, of course. Oil and natural gas production and mining were fully nationalised and quickly became the primary source of income for the state. Despite still suffering from similar issues of corruption and embezzlement as pre-revolutionary Indonesia, high oil prices in the 1970s would allow Nusantara to eventually achieve economic stability and allow investment in large infrastructure projects. In order to deal with the issues of regional smallholder opposition to Nusantaran land reform policies and overpopulation of Java in one policy: transmigration. So-called

Persatuan Desa (Unity Villages) were established throughout Sumatra, Borneo and Sulawesi. These villages were defined by collective ownership and the integration of the PKN into daily life, although they lacked the "struggle sessions" of their Chinese equivalents. Another difference to the Chinese collective villages was the establishment of red militias in every village, comprised of young men and women, and designed to defend the settlements against interference from neighbours, such as indigenous Dayaks on Borneo or followers of imams in Sumatra. The biggest flare-up in opposition to the transmigration policy was the 1973 Aceh Uprising. The uprising began as a regionwide protest against the Unity Villages, demanding the dissolution of those villages and the departure of their inhabitants from the province. During these protests, effigies of local PKN boss Muhamad Samikidin were burnt and in response, the military was sent in to restore order. An insurgency of Islamist rebels supported by local imams and supplied clandestinely by Malaya would be crushed by November 1974. Nusantara would retaliate against Malaya for support of Acehnese rebels by increasing clandestine support for communist insurgents on the Malaya peninsula. In order to link the Unity Villages to major townships, rail links throughout the country were expanded significantly. A few years before Aidit's dominance was established in Indonesia, the SOBSI trade union confederation had started to drift away from the party line, much to the PKI leadership's chagrin. This was largely caused by SOBSI encouraging industrial action at nationalised industrial sites, putting the interests of their membership above the national interest as a whole, or at least that was how it was seen by Aidit. A short burst of purges ousted SOBSI leaders who maintained an independent streak or who had been affiliated with the PNI.

Revolutionary Nusantara President Sukarno dining with Mao Tse-Tung

Internationally, Aidit and Sukarno threw their lot in with the the Chinese in their dispute with the Soviet Union. Whilst not openly hostile to Moscow, the PKN leadership saw the Chinese path to socialism as more relevant to the Nusantaran situation; like China, the number of industrial workers in Nusantara were far exceeded by the rural peasantry. Elements of feudalism still lingered in the form of the Islamic clergy and the Yogyakarta Sultanate, the latter of which was quickly toppled and Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX placed in house arrest, albeit in a relatively luxurious gilded cage in his palace. The particular situation of Nusantara led to an interesting duality in national economic development. The Unity Villages aped the rural communes of China, but the nationalised resource extraction industries allowed Nusantara to engage more heavily in a degree of state involvement in international markets and localised industrial development in processes such as oil refining. Nusantara also remained an OPEC member. The Nusantaran government sought especially close ties not only with China, but also with Vietnam and Korea. Like China and Korea, throughout the 1970s, Jakarta engaged in a significant expansion of naval capacity, although unlike the PLAN, the

Tentara Nasional Nusantara Angkatan Laut (Nusantara National Military-Naval Force; TNNAL) would remain a largely brown-water force, albeit with a couple of missile cruisers attached. The naval buildup was intended to aid in force projection and protect from intrusions from Malaya, the Philippines and the Oceanian Treaty Organisation. Multiple skirmishes between Nusantara and South Maluku and West Papuan ships occurred throughout this period, and as such Royal Australian Naval units were based at Ambon. The presence of the Australians in South Maluku was rabidly denounced by the government of Revolutionary Nusantara, which claimed both South Maluku and West Papua as territories of Nusantara occupied by "imperialists and their running dogs". These confrontations intensified the rift between Moscow and Jakarta, as in various international socialist forums the CPSU leadership denounced "adventurism in Asia" that "exacerbate existing tensions" and "threaten the existing successes of socialism in the Pacific region". Between 1974 and 1976, Jakarta cut off diplomatic relations with Moscow, forcing Indochina to act as a go-between. During the Tibetan campaign, Jakarta made accusations in the United Nations of "wannabe Great Power chauvinism" by Delhi. In response, the Bharati diplomats denounced "the robbery and abuse of Hindus and Buddhists in the Indonesian archipelago", being sure to not acknowledge the new name of Nusantara. In the late 1970s, with the healing of the Sino-Soviet split, Jakarta reestablished relations with Moscow and began to solicit technology transfer from the Soviets, especially interested in the development of nuclear power grids.

Despite the best efforts of Chinese doctors, Sukarno passed away from kidney failure in February 1972. Aidit became the new President, formalising his leadership of Nusantara. As President, Aidit took a personal interest in several areas, most notably the promotion of Nusantaran cinema. Entertainers such as Nun Zairina, Gordon Tobing and Bing Slamet were featured in films promoting values deemed desirable to the government. Zairina's portrayal as a beautiful and ambitious young woman limited by the feudal regime in Yogyakarta made her a star throughout the communist world. The film,

Yogyakarta Merah, was set against the backdrop of the 1969 deposition of the local sultan. More popular with local audiences was

Rakyat Tersenyum Menantang, a musical comedy starring Gordon Tobing about the inhabitants of a Unity Village and their humiliations of a dour old imam who tries to undermine them.

On 7th December, 1975, Nusantara became involved in East Timor. Preoccupied with war in Africa and revolution at home, the Portuguese had largely abandoned East Timor to its fate. In the small nation, a civil war was fought between the two predominant factions, the left-wing

Frente Revolucionária de Timor-Leste Independente also known as "Fretilin" and the conservative

União Democrática Timorense (Timorese Democratic Union, UDT). Fretilin had resisted a UDT coup attempt and unilaterally declared independence from Portugal on 28th November 1975. Australian denunciations of Fretilin's anti-Lisbon coup spooked Fretilin, who requested that Nusantara troops be stationed in the country to protect from a potential Australian-backed UDT counter-coup. Whilst Portugal seemed to legitimately not care about the status of East Timor (perhaps even relieved that an economic liability had been snapped up by someone else), Australia immediately began posturing. Not only were they trying to limit Nusantaran expansion, but they also sought exploitation of potential future natural gas and oil reserves located in the Timor Gap between the island of Timor and Darwin. Upon entry into East Timor, Nusantara troops immediately began to assist Fretilin forces with the capture and forceful disarmament of UDT members. Of the three Carrascalão brothers who led the UDT, João and Mário were able to escape to Australia, whilst Manuel was captured, tortured and murdered by Nusantara troops. One of the founding members of Fretilin, Francisco Xavier do Amaral, was named the first President of East Timor. However, he soon fell out with the Nusantara military leadership in his country. He sought a withdrawal of Nusantaran troops and the establishment of a collective security agreement with Jakarta to protect against a return of the UDT. The Nusantara military refused, saying that the risk of Australian adventurism was too great. Relations between locals and the Nusantara military were also getting increasingly tense. Even putting aside misunderstandings as a result of language barriers, some of the army men would pass the time getting drunk and harassing locals, with little to no discipline upheld by their commanders. Seeing themselves as liberators, the Nusantara troops developed a fairly entitled attitude, helping themselves to food, drinks and the occasional local woman, regardless of the consternation this caused with the locals. Amaral would be ousted by Nicolau dos Reis Lobato, who would accept to negotiate with Jakarta around the potential issue of incorporation into Nusantara. It was in the end decided, largely by Aidit, that the Democratic Republic of East Timor would be integrated into Nusantara as the autonomous province of Timor Timur. Fretilin would be allowed to continue existence as a political formation governing Timor Timur.

Falintil, the armed wing of Fretilin, would be the only ground forces permanently stationed in the area, but would be subject to the authority of the Nusantara Interior Ministry. Portuguese would be allowed to be used in a co-official capacity. This annexation would cause a split in the party, with many of the non-Marxists in Fretilin fleeing to Australia and banding together with the UDT exiles.

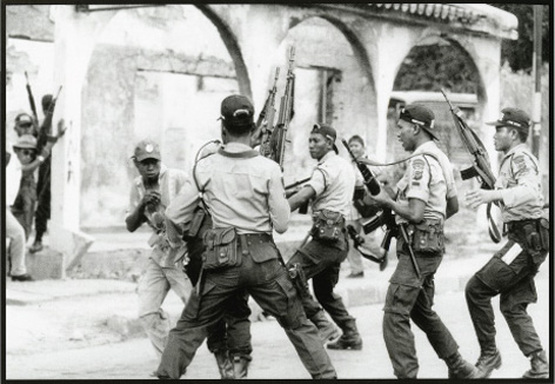

Falintil militia harassing political opponents

===

[245] His Chinese name in pinyin was

Xiāo Yùcàn. Long-time readers may recall that we're using Wade-Giles orthography here for reasons outlined in the China updates.