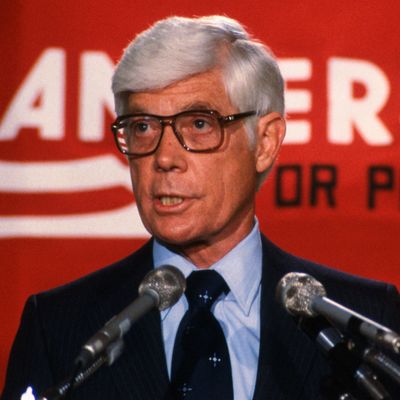

Evan Mecham (Republican)

“I’ll hire blacks as long as they can do the cotton-picking job.”

The rise of Evan Mecham was a long and arduous thing. Mecham was for a long time known as ‘the Harold Stassen of Arizona’ because, like the quixotic liberal Republican, Mecham was a perennial also-ran. After a 2 year stint in the Arizona Senate, Mecham made a failed bid for Arizona GOP Chair and ran for governor three times without success. Most assumed Mecham’s fourth run for Governor in 1982 would end the same way, but Mecham got lucky. First, as the most right-wing candidate in the race, he got a lot of support from Reaganites still sore over the victory of Anderson in 1980 and Mecham hinting at some attempt to sabotage Governor Reagan probably helped him seal the deal in the primary. In the general, Mecham likely would have lost had it not been for the creation of the Justice Party. Businessman William R. Schultz-who had narrowly lost a Senate race to Barry Goldwater as a Democrat 2 years before-saw an opportunity to mount a bid for governor without having to face a primary against incumbent Governor Bruce Babbitt. Schultz ultimately won 25% of the vote to Babbitt’s 37%-and Mecham’s 38%.

As Governor, Mecham spent a lot of time blocking things. A bill to make statewide elections go to top two runoffs was vetoed and the state’s income tax was slashed. Mecham also blocked efforts to establish a state-level Martin Luther King Day holiday, citing alleged ties between King and communist figures. Mecham also pushed to have federal lands within Arizona handed over to the state government, though neither Anderson nor Edwards were receptive. Mecham also developed a reputation for making many statements that were bigoted-defending the use of the slur ‘pickaninny’ and telling an audience of black people ‘what you really need are jobs.’ Mecham’s comments earned him condemnation from many across the political spectrum, but the defiant Governor’s willingness to say such things endeared him to hard-right voters. Mecham, despite these controversies, managed to win reelection in 1986-though it was quite close as Babbitt managed to come within 1,000 votes of returning to the governor’s mansion. Mecham’s second term was largely more of the same until 1987, when he announced he would be running for President.

Mecham had a clear strategy entering the race. Since Reagan, the conservative movement was still looking for a clear champion. In 1984, Senator Jesse Helms, Representative Barry Goldwater, Jr., Senator Paul Laxalt and Representative Phil Crane had all tried to frame themselves as the heir to Reagan only for the number of imitators to divide the vote enough for Baker to claim the nomination. In 1988, Mecham believed he could seize the whole lane for himself. Goldwater, Jr. and Crane had given up their House seats to run in 1984 and Helms had lost reelection, leaving only Laxalt and Representative Jack Kemp to compete with him. And when the debates went underway, neither could keep up with him-Kemp was too awkward and stilted and Laxalt lacked the vision. Mecham had the vision. He promised he would restore America to glory, cast aside the special interests holding the country back and unleash the American dream. The primaries were more or less over by Super Tuesday.

Many assumed Mecham would tone things down for the general election. But he didn’t. Mecham vowed to crush communism in the Western Hemisphere for good and then roll it back overseas, alarming the Soviets. He declared his intent to end ‘special treatment’ for the LGBT community which he decried as ‘a community of perverts corrupting our way of life.’ Mecham also vowed to crack down on illegal immigration, gleefully agreeing when Anderson accused him of seeking to carry out mass deportations. Mecham also promised to ‘unshackle the police’ to deal with rising crime rates. Mecham didn’t just offer red meat, however. He also declared he would cut taxes, return much federal land to the states and defund the ‘socialized medicine’ of AmeriCare-music to the ears of corporate America, who funneled record amounts of donations into his campaign. Mecham also drew attention for how he intended to use the presidency-namely as a weapon against those he didn’t like. In addition to criminals, Mecham vowed to crush ‘pinko agitators’ at home and jail crooked politicians and journalists. Many warned this was a threat to the future of American democracy, but the public seemingly didnt hear these concerns as Mecham entered the White House.

Mecham did not waste any time. His chief strategist Lee Atwater had helped assemble a cabinet shortlist that was the most conservative one that could feasibly get confirmed by the Senate. Helms returned to DC to head the Department of Defense and Crane selected to serve at the Treasury. The closest to a moderate in his cabinet was his former rival Jack Kemp at HUD. His most controversial nominee was for Attorney General: Robert Bork. Bork’s status as a supporter of Nixon and expansive executive power raised many red flags. The Senate tied in their vote but the Vice President ensured Bork got the job. Several Republicans who voted to confirm Bork would later express regret for doing so, as Bork proceeded to wield the Justice Department as a cudgel. Investigations into any Mecham allies were slow-walked and Bork refused to appoint any special counsels. On the other hand, Bork was quite liberal with legal challenges against opponents of Mecham-the most famous instance being filing a suit against Gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson for allegedly leaking information protected by executive privilege. The case against Thompson was quickly dismissed by the courts, but the fact it was filed at all sparked mass protests.

Speaking of mass protests, Mecham faced many of those. His administration’s hardline immigration stance and efforts to roll back Roe v. Wade meant many didn’t even wait past the inauguration to protest. His sabotage of AmeriCare bred backlash too-Mecham in essence made it so poor quality enrollment dropped by 33% in his first two years in office even as full abolition faltered in Congress. But the real wave of discontent would ensue from foreign policy. Mecham, like Edwards, viewed foreign policy as a tool to build domestic support. Unlike Edwards, Mecham was not as concerned about the optics of another quagmire in a tropical location and so he began sending ‘military advisors’ into Nicaragua. Not as many active duty troops were deployed there as in Vietnam, but it was enough to animate opposition. More consequential, however, was the impact of U.S. operations in Nicaragua on relations with Cuba. Cuba had been supporting the left-wing Sandinista forces and stepped up this support as U.S. involvement grew. One confrontation between American ‘advisors’ and Cuban volunteers ended in a dozen Americans dead and Mecham vowing to finally eliminate the communist threat in the country.

US soldiers in Cuba, 1991

Mecham hoped that he could have a quick and easy victory over Cuba but these hopes were dashed when it took weeks to fight to the outskirts of Havana. Even then, despite a relentless American bombing campaign, Castro remained defiant and Cuban resistance would not yield. The war quickly claimed hundreds of lives and by the midterms, casualties on the American side numbered 2,000 killed, captured or wounded soldiers. The midterms were brutal for the Republicans as a result-many races saw them locked out as the Justiceites and Democrats vied for dominance. The Rainbow Coalition got seats in Congress for the first time thanks to rallying strong antiwar support. The Justice Party saw major gains as well, owing to Anderson condemning the war ahead of most Democrats, who framed objections more around the how of the war than the why. The Constitution Party-which had endorsed Mecham in 1988-broke from him over the war and their two members of Congress (Larry McDonald and Ron Paul) held their seats by strong margins. The Republicans battering was so bad that after the midterms they were reduced to barely over 130 seats in the House and only held 39 seats in the Senate.

Most presidents would recognize a need to pivot after such an electoral disaster, but Mecham was not most presidents. He claimed the Justice and Democratic Parties had formed a ‘coalition of sedition’ to block him. These cries of a ‘corrupt bargain’ were met largely with eye rolls, but Mecham had Bork open investigations into possible illegal fundraising and voter fraud by his rival parties. Bork kept the investigations going as long as possible, but faced with an increasingly angry Congress, was forced to close them with a verdict of ‘no conclusive evidence’ of wrongdoing. Bork instead offered Mecham an alternative of targeting radical protestors, which Mecham eagerly approved. Hundreds of prominent antiwar activists were swept up in FBI raids and slapped with charges that sent many to prison for years. But rather than cow the opposition, it in fact made them angrier, especially when Chicago lawyer Barack Obama was detained after defending a quarter of activists in federal court and turned up dead in his cell-officially of suicide, but most doubted this claim.

The events surrounding the Louisiana gubernatorial election of 1991 further cemented the decline of Mecham’s reputation. Incumbent Democrat Buddy Roemer was facing declining approval and faced a strong intra-party challenge from State Treasurer Mary Landrieu. Meanwhile, the state’s Republican leaders were largely rallying around Fox McKeithen, the Secretary of State who newly-minted member of the GOP with a political pedigree (his father John McKeithen had been governor before). However, there was another candidate-Louisiana House member David Duke, former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Duke ran as a far-right populist who tied himself closely to the President. Mecham did not embrace Duke in the first round, but nor did he answer GOP leadership’s pleas to endorse McKeithen, with Mecham viewing him with suspicion thanks to his party switch. In the end, Duke actually won a plurality in the first round, with Roemer narrowly claiming second. Faced with the specter of a Klansman, many Republican leaders-including Senate Leader Howard Baker, RNC Chairman James Baker and even House Minority Leader Trent Lott-spoke out against Duke, some even openly endorsing Roemer, including McKeithen. Absent from that list was Evan Mecham, who after some soul-searching issued an endorsement of Duke-tepid and full of qualifications, but an endorsement all the same. The endorsement probably helped Duke get as close as he did to victory-Roemer won with 53% of the vote to Duke’s 47%-and further solidified Mecham’s image as a racist, especially when Duke dropped the pretense of abandoning his neo-Nazi beliefs to accuse the Jews of rigging his election less than a year afterwards.

By 1992, Mecham found himself with a public approval rating of 23%. Corruption accusations led to an impeachment attempt was in spring of 1992 that Mecham survived by dint of a mere 3 votes in the Senate. Massachusetts Governor William Weld mounted a primary challenge against Mecham going into 1992 and when it became clear Mecham would win, the moderate Republican announced a defection to the Libertarian Party, which received him warmly (or at least the wing of the party the Koch Brothers had spent the last 12 years building up against the likes of Murray Rothbard warmly received him). The Constitution Party also decided to run a ticket against Mecham, nominating party founder Larry McDonald and Texas Representative.Ron Paul. Meanwhile, to the left, many wanted to ensure Mecham would be buried. Leaders in the Rainbow Coalition and the Democratic and Justice Parties engaged in talks about a unity ticket to end the threat Mecham posed for good. The talks ultimately saw the Democrats pull out-their frontrunner, former Vice President Joe Biden, was not willing to veer too far left on policy and was worried about seeming too soft if he went hardline against the war and many Democrats assumed they could win without a coalition-but the Justice Party was able to reach agreement with the Rainbow Coalition to form a unity ticket for 1992.

In the lead up to the first round, many assumed Mecham would be locked out of the runoff, but Mecham outperformed his approval ratings, narrowly lapping the Democrats by less than 1%. Mecham barreled towards the runoff accusing the Justice Party of being crypto-communist. However, Mecham’s cries fell on deaf ears. A poor economy alongside the scandal and authoritarianism and warmongering was too much and both Weld and Biden endorsed the Justice Party ticket to bring an end to his administration. And sure enough, that was what America voted for-it wasn’t’ close either, as Mecham won just over a third of the vote. But Mecham wasn’t done yet. He had his personal lawyer Roy Cohn file lawsuits accusing certain precincts of voter fraud. The courts tossed these lawsuits, but Mecham expected that. He told Bork to prepare for a new plan-a plan to declare the election invalid, the political system rotten to the core and seize as many ballots as possible, all to overturn the election and keep Mecham in office for another four years.

Even for Bork, this was stunning. He held an expansive view of presidential power and skepticism of direct democracy, but this was too far even for him. He quietly contacted the Vice President, hoping he could talk some sense into Mecham. However, the Vice President reached a different conclusion as to what had to be done. This was nothing less than a betrayal of the oath Mecham swore. He convened the cabinet, shared the plan and declared that he felt Mecham was no longer fit to serve. He was attempting to invoke the 25th Amendment and declare Mecham unfit for office. Protests erupted quickly from Defense Secretary Helms, but HUD Secretary Kemp backed the move quickly. Crane surprised by agreeing Mecham was unfit before Bork too surprised (at least the Vice President) by declining to do so. And so it went deadlocked until it got to the Secretary of State, who by pattern (Labor Secretary George Shultz had just voted to remove) and reputation (an ideological conservative who was seen as moderate enough to put fires out overseas but mostly was a loyalist) should’ve sustained the tie. But when Dick Cheney growled “That bastard has to go”, that was that. The cabinet officially voted to remove Mecham at 2:03 AM on December 2nd, 1992. Mecham did not take his removal well, ranting and raving both as he was told and after his removal. Mecham’s removal also angered large swathes of the Republican base-some of whom would turn to violence in the years to come. Mecham worked tirelessly to maintain influence in the GOP despite his removal-a conflict likely responsible for the party’s ultimate fate, but that is a story for later.

Mecham’s post-presidency memoir, largely a screed against his removal via the 25th Amendment (notably not officially considered impeachment despite the tile). The memoir was published in 1996.

As for reputation, Mecham’s is absolutely dismal. His policies are seen as nothing short of disastrous on almost every level-an economic recession that while not the deepest was all but ignored in favor of a quagmire war overseas, corruption and abuses of power and so on mean outside of the far-right fringe, almost no one has anything nice to say about Evan Mecham. Historians have ranked him 44th out of 48 presidents, with only the likes of James Buchanan and Herbert Hoover ranked worse than him.