Part 1: Sun Power

Hello,

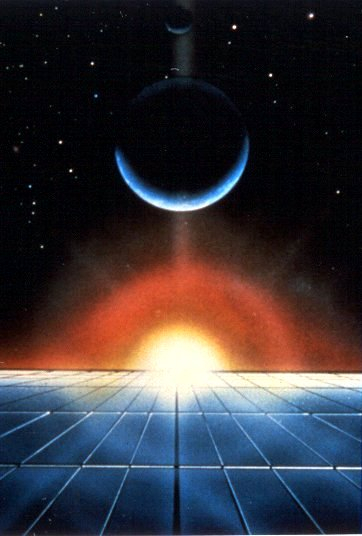

SPS is a concept I’ve known for a little under a year but been invested in ever since I discovered it. The idea of building these vast structures to beam power down to the earth just sounded magical to me. Looking further and further into it has finally brought me to a point of confidence where I can finally write something I’m proud of. Branching off of additional concepts of the time, I hope to create not just a “what if story” of SPS, but a larger story of how space can be explored and expanded into a new world for everyone.

Before we get started I’d like to first admit this is my first alternate history project I’m publicly posting. While I’m going to strive for an appropriate level of accuracy. My main goal is to create something I personally feel proud about creating, and hope it’s something other people can enjoy too. With that being said, I hope you enjoy reading Solar age.

Part 1: Sun Power

Space-Based Solar Power marked an inflection in the United States space program. The decline in NASA funding after Apollo and the struggle to begin the Space Shuttle program lead to a change in spaceflight. With the marvels of Apollo winding down, the Space Shuttle became the “flatbed truck of space”. Instead of a ship of exploration, the Shuttle was a vehicle to enable routine access to space for a variety of purposes, but many viewed this lack of specific purpose as a lack of ambition. The approval of efforts to develop Space Based Solar Power and the move towards mass manufacturing and industry in space would show that even the routine, executed at great enough scale for grand purposes could have its own ambition. The change, marked over the end of the century, would define a transformation of the potential of space for applications on Earth. The combined impacts of the two programs would define the next century in space.

With the founding of the Department of Energy in 1977, it was tasked with securing America’s future in energy. Among other options such as coal, natural gas, ground-based wind and solar, and nuclear, Space-Based Solar Power stood out in ambition. Colossal satellites high above the Earth, beaming energy from the sun back down to Earth, unaffected by the night or weather. Studies done in 1975 by NASA had proven the requirement of wireless power transmission. The concept of Solar Power Satellites (SPS) could lay the groundwork for a clean and renewable form of energy, constantly powering the United States for centuries to come. By the later half of the 1970s, NASA and the DOE had begun proposals for the Solar Power Station program, examining precursor programs consisting of both structural studies of full-sized satellites and ground and space testing of enabling technologies. As the concept was presented to Congress and to the public in seminars and news media, the national perspective of space began to transform slowly but surely. The idea of using space not just as a means of exploration began to take hold. Around the country, the possibility of people living and working in space began to revive a national pride in the space program. From the legacy of Apollo came a projected future full of industry, exploration, science, and expansion from the realm of Earth and into the cosmos.

At the start of 1975, the SPS design was in its infancy. Major details such as the method of power generation and transmission still required additional study and refinement. Within Boeing, initial designs had preferred thermal turbines, which used heat from the sun to spin turbines and generate electricity. However, technology had marched on from the aged-old means, and by 1980, the design progressed to solar arrays for simplicity. Though the efficiency of solar panels was lower than thermal turbines, the benefit of a solid state system was enough of a payoff to prefer solar panels even with the larger area required. Similar debates existed over power transmission. Differing methods of microwave transmission were under consideration, alongside other transmission proposals such as lasers.

While details of the satellite design were still debated by 1979, the larger vision of the program was gaining clarity. Large space freighters would provide the bulk of transportation into Low Earth Orbit, where construction bases would be built for the assembly of station elements. Final assembly of stations would take place in Geostationary orbit by a smaller base. The program in whole, would cost upwards of 2 trillion dollars, and take the effort of the entire country. Alongside these studies came additional supportive goals. After all, if the technology was developed to transport and build massive orbital structures, then why not expand out to develop more than just SBSP? While creating a space based source of power for the United States was the main goal of the proposal, the industrial expansion into space became the first pioneers into the next era of spaceflight.

NASA and the Doe continued mapping out the future in the space industry and how to exploit it, Washington had a different view. While NASA worked on the “could” aspects of SPS, Washington was getting ready to debate the “should” half of SPS. In 1979, Congress took into consideration to create a bill funding NASA and the DOE to turn the SPS preliminary studies into a full program proposal–not approval to execute a program at the scope of SPS or even to test elements, but merely approval to develop a plan. Within the House, support for an SPS bill brought approval swiftly, and moved it to the Senate almost as quickly as it arrived. The serious battle was held in the Senate. Within the DoE, management was heavily influenced by the nuclear program, which was proposed for the same role as SPS. With this backing, Senators opposing the expense of the program proposed nuclear as a faster and lower development alternative. On April 7th, the proposal came to a vote, with the future of the program in the balance. Ultimately, the efforts by NASA to sway key Senators towards SPS worked. While the SPS program received funding for a proposal, funding for nuclear research would still be given to the DOE, becoming a mild success in the wake of 3 Mile Island. The possibility of space growing into a center of industry and applications for Earth brought a wave of public excitement about the future of spaceflight.

News of the SPS program sparked interest around the world such as in Europe, the Soviet Union, and Japan, but for the moment little action was taken outside of the United States. While the SPS program had only begun with a narrow compromise, the first steps towards SBSP were set in stone by congress. Now with the program in its infancy, the proper architecture must be developed for the construction of SPS. By 1980, the program reached its next milestone in developing a complete system for SPS, and made its final program proposal to congress. Alongside this, NASA continued development of the Space Shuttle, which would play a leading role in SPS throughout the early phases of the program.

With the call from Washington to continue on with the SPS program NASA authorized contractors to continue work on their own architectures. NASA had retained two primary contractors, who each offered their own designs for the details of the program: Rockwell and Boeing. The two contractors offered different solutions to key aspects of the program, such as in transportation from Earth. Within Rockwell, the preferred design was a massive single stage to orbit known as Starraker, and on the opposite end of the proposals was the Boeing Space Freighter. The Space Freighter was instead a two stage design, both of which flew back to the launch site similar to the Space Shuttle. Additional concepts occupied middle ground between these two contractors such as the Grumman design, a middle ground using a two stage two orbit design, but landing in the sea instead of like a plane.

Above the Earth another configuration battle was being fought. The question of construction location was solved early. Engineers had been forced to consider where stations would be assembled. Stations within GEO could support a consistent construction of satellites, but placed the construction crew further from Earth. Though LEO stations couldn’t assemble an entire satellite and required final assembly work in GEO, a base location had been commonly agreed upon due to the safety concerns for crews on orbit. Between 1978 and 1980, the final designs of the bases would be refined by individual contractors, but overall the common design would use a higher level of automation for worker safety. Within a base hundreds of people would live and work on the base, mostly living in a shirt sleeve environment with EVA intended only in case of emergency. Even the shape of the SPS platform was up for debate. Basic construction stayed the same, using miles and miles of truss assembled on orbit to build the individual stations, but the specific design of the stations differed between the major and minor contractors Rockwell proposed a trench shaped station, using indented concentrator panels to generate power, while Boeing offered a different design which used a large rectangular shape instead for the main frame of the station.

With a strong collection of proposals, NASA continued along the path to SPS. With 1980 approaching, the SPS studies came to a close as NASA prepared to select the prime contractor for the actual precursor program. The countdown was on for STS-1, the debut of the Space Shuttle Columbia and the next goal in NASA’s future plans for space. Now with a future of routine access to space supporting SPS, the impending launch of Columbia would mark not just the first launch of the Space Shuttle, but the beginning of a new age in spaceflight. The launch of Columbia would carry the potential for the next big step in space–industrialization and applications in space that could benefit everyone on Earth.

Authors Note:

Sun Power was a book written in 1995 by Ralph Nansen. It’s genuinely one of my favorite books and is the main reason why I wanted to actually write an SPS timeline instead of just collecting info on it, which is why I decided to name the first part after it.

SPS is a concept I’ve known for a little under a year but been invested in ever since I discovered it. The idea of building these vast structures to beam power down to the earth just sounded magical to me. Looking further and further into it has finally brought me to a point of confidence where I can finally write something I’m proud of. Branching off of additional concepts of the time, I hope to create not just a “what if story” of SPS, but a larger story of how space can be explored and expanded into a new world for everyone.

Before we get started I’d like to first admit this is my first alternate history project I’m publicly posting. While I’m going to strive for an appropriate level of accuracy. My main goal is to create something I personally feel proud about creating, and hope it’s something other people can enjoy too. With that being said, I hope you enjoy reading Solar age.

Part 1: Sun Power

Space-Based Solar Power marked an inflection in the United States space program. The decline in NASA funding after Apollo and the struggle to begin the Space Shuttle program lead to a change in spaceflight. With the marvels of Apollo winding down, the Space Shuttle became the “flatbed truck of space”. Instead of a ship of exploration, the Shuttle was a vehicle to enable routine access to space for a variety of purposes, but many viewed this lack of specific purpose as a lack of ambition. The approval of efforts to develop Space Based Solar Power and the move towards mass manufacturing and industry in space would show that even the routine, executed at great enough scale for grand purposes could have its own ambition. The change, marked over the end of the century, would define a transformation of the potential of space for applications on Earth. The combined impacts of the two programs would define the next century in space.

With the founding of the Department of Energy in 1977, it was tasked with securing America’s future in energy. Among other options such as coal, natural gas, ground-based wind and solar, and nuclear, Space-Based Solar Power stood out in ambition. Colossal satellites high above the Earth, beaming energy from the sun back down to Earth, unaffected by the night or weather. Studies done in 1975 by NASA had proven the requirement of wireless power transmission. The concept of Solar Power Satellites (SPS) could lay the groundwork for a clean and renewable form of energy, constantly powering the United States for centuries to come. By the later half of the 1970s, NASA and the DOE had begun proposals for the Solar Power Station program, examining precursor programs consisting of both structural studies of full-sized satellites and ground and space testing of enabling technologies. As the concept was presented to Congress and to the public in seminars and news media, the national perspective of space began to transform slowly but surely. The idea of using space not just as a means of exploration began to take hold. Around the country, the possibility of people living and working in space began to revive a national pride in the space program. From the legacy of Apollo came a projected future full of industry, exploration, science, and expansion from the realm of Earth and into the cosmos.

At the start of 1975, the SPS design was in its infancy. Major details such as the method of power generation and transmission still required additional study and refinement. Within Boeing, initial designs had preferred thermal turbines, which used heat from the sun to spin turbines and generate electricity. However, technology had marched on from the aged-old means, and by 1980, the design progressed to solar arrays for simplicity. Though the efficiency of solar panels was lower than thermal turbines, the benefit of a solid state system was enough of a payoff to prefer solar panels even with the larger area required. Similar debates existed over power transmission. Differing methods of microwave transmission were under consideration, alongside other transmission proposals such as lasers.

While details of the satellite design were still debated by 1979, the larger vision of the program was gaining clarity. Large space freighters would provide the bulk of transportation into Low Earth Orbit, where construction bases would be built for the assembly of station elements. Final assembly of stations would take place in Geostationary orbit by a smaller base. The program in whole, would cost upwards of 2 trillion dollars, and take the effort of the entire country. Alongside these studies came additional supportive goals. After all, if the technology was developed to transport and build massive orbital structures, then why not expand out to develop more than just SBSP? While creating a space based source of power for the United States was the main goal of the proposal, the industrial expansion into space became the first pioneers into the next era of spaceflight.

NASA and the Doe continued mapping out the future in the space industry and how to exploit it, Washington had a different view. While NASA worked on the “could” aspects of SPS, Washington was getting ready to debate the “should” half of SPS. In 1979, Congress took into consideration to create a bill funding NASA and the DOE to turn the SPS preliminary studies into a full program proposal–not approval to execute a program at the scope of SPS or even to test elements, but merely approval to develop a plan. Within the House, support for an SPS bill brought approval swiftly, and moved it to the Senate almost as quickly as it arrived. The serious battle was held in the Senate. Within the DoE, management was heavily influenced by the nuclear program, which was proposed for the same role as SPS. With this backing, Senators opposing the expense of the program proposed nuclear as a faster and lower development alternative. On April 7th, the proposal came to a vote, with the future of the program in the balance. Ultimately, the efforts by NASA to sway key Senators towards SPS worked. While the SPS program received funding for a proposal, funding for nuclear research would still be given to the DOE, becoming a mild success in the wake of 3 Mile Island. The possibility of space growing into a center of industry and applications for Earth brought a wave of public excitement about the future of spaceflight.

News of the SPS program sparked interest around the world such as in Europe, the Soviet Union, and Japan, but for the moment little action was taken outside of the United States. While the SPS program had only begun with a narrow compromise, the first steps towards SBSP were set in stone by congress. Now with the program in its infancy, the proper architecture must be developed for the construction of SPS. By 1980, the program reached its next milestone in developing a complete system for SPS, and made its final program proposal to congress. Alongside this, NASA continued development of the Space Shuttle, which would play a leading role in SPS throughout the early phases of the program.

With the call from Washington to continue on with the SPS program NASA authorized contractors to continue work on their own architectures. NASA had retained two primary contractors, who each offered their own designs for the details of the program: Rockwell and Boeing. The two contractors offered different solutions to key aspects of the program, such as in transportation from Earth. Within Rockwell, the preferred design was a massive single stage to orbit known as Starraker, and on the opposite end of the proposals was the Boeing Space Freighter. The Space Freighter was instead a two stage design, both of which flew back to the launch site similar to the Space Shuttle. Additional concepts occupied middle ground between these two contractors such as the Grumman design, a middle ground using a two stage two orbit design, but landing in the sea instead of like a plane.

Above the Earth another configuration battle was being fought. The question of construction location was solved early. Engineers had been forced to consider where stations would be assembled. Stations within GEO could support a consistent construction of satellites, but placed the construction crew further from Earth. Though LEO stations couldn’t assemble an entire satellite and required final assembly work in GEO, a base location had been commonly agreed upon due to the safety concerns for crews on orbit. Between 1978 and 1980, the final designs of the bases would be refined by individual contractors, but overall the common design would use a higher level of automation for worker safety. Within a base hundreds of people would live and work on the base, mostly living in a shirt sleeve environment with EVA intended only in case of emergency. Even the shape of the SPS platform was up for debate. Basic construction stayed the same, using miles and miles of truss assembled on orbit to build the individual stations, but the specific design of the stations differed between the major and minor contractors Rockwell proposed a trench shaped station, using indented concentrator panels to generate power, while Boeing offered a different design which used a large rectangular shape instead for the main frame of the station.

With a strong collection of proposals, NASA continued along the path to SPS. With 1980 approaching, the SPS studies came to a close as NASA prepared to select the prime contractor for the actual precursor program. The countdown was on for STS-1, the debut of the Space Shuttle Columbia and the next goal in NASA’s future plans for space. Now with a future of routine access to space supporting SPS, the impending launch of Columbia would mark not just the first launch of the Space Shuttle, but the beginning of a new age in spaceflight. The launch of Columbia would carry the potential for the next big step in space–industrialization and applications in space that could benefit everyone on Earth.

Authors Note:

Sun Power was a book written in 1995 by Ralph Nansen. It’s genuinely one of my favorite books and is the main reason why I wanted to actually write an SPS timeline instead of just collecting info on it, which is why I decided to name the first part after it.

Last edited: