You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Reds vs. Blues, an alternate Cold War

- Thread starter Analytical Engine

- Start date

Great timeline!  If possible, do you have a list of American Presidents so far?

If possible, do you have a list of American Presidents so far?

Great timeline!If possible, do you have a list of American Presidents so far?

I do, in fact:

Andrew Johnson (Dem) - 1865-69

Ulysses S. Grant (Rep) - 1869-77

Samuel J. Tilden (Dem) - 1877-81

James G. Blaine (Rep) - 1881-89 (ATL character)

Benjamin Harrison (Rep) - 1889-93

Mathew J. Beaconsfield (Rep) - 1893-1901 (ATL character)

Theodore Roosevelt (Rep) - 1901-09

Adrian Buchanan (Dem) - 1909-13 (ATL character)

Jefferson Lowry (Rep) - 1913-21 (ATL character)

I do, in fact:

Andrew Johnson (Dem) - 1865-69

Ulysses S. Grant (Rep) - 1869-77

Samuel J. Tilden (Dem) - 1877-81

James G. Blaine (Rep) - 1881-89 (ATL character)

Benjamin Harrison (Rep) - 1889-93

Mathew J. Beaconsfield (Rep) - 1893-1901 (ATL character)

Theodore Roosevelt (Rep) - 1901-09

Adrian Buchanan (Dem) - 1909-13 (ATL character)

Jefferson Lowry (Rep) - 1913-21 (ATL character)

Thank you!

You have talked about an "Anti-Socialist element of the League of Nations". However, logically, you wouldn't need anything anti-socialist if you don't have any socialists to counter. So: Where are the reds?

EDIT: Russia would be quite uncreative (because it's OTL), France I doubt because it lost the war and would more likely go heavily nationalist, so Germany? Will maybe a MEVAR (Mitteleuropäische Vereinigte Arbeiterrepubliken)-like construct out of Germany and Austria-Hungary be created? That would be creative!

EDIT: Russia would be quite uncreative (because it's OTL), France I doubt because it lost the war and would more likely go heavily nationalist, so Germany? Will maybe a MEVAR (Mitteleuropäische Vereinigte Arbeiterrepubliken)-like construct out of Germany and Austria-Hungary be created? That would be creative!

You have talked about an "Anti-Socialist element of the League of Nations". However, logically, you wouldn't need anything anti-socialist if you don't have any socialists to counter. So: Where are the reds?

Shhh, spoilers.

EDIT: Russia would be quite uncreative (because it's OTL), France I doubt because it lost the war and would more likely go heavily nationalist, so Germany? Will maybe a MEVAR (Mitteleuropäische Vereinigte Arbeiterrepubliken)-like construct out of Germany and Austria-Hungary be created? That would be creative!

All I will say is that it will be complicated, and you will find out soon.

Next post shouldn't be too far off once I've incorporated the information on Australia I've just been researching, and I've made sure all of the footnotes are sorted out.

Speaking of the update, here it is

Chapter 8

In which is presented an overview of the United Kingdom after the war

The war had been hard for Britain, and its empire. Many millions of men (well, mostly men) of fighting age (and some too young or old) were sent out onto the battlefield. They came from all over the empire to fight for king and country. Some came back in one piece, other came back missing pieces. And all too many of them never came home at all, and are still lying in some foreign field that is forever [insert country of choice here].

Meanwhile, back in Britain, things weren’t easy either. With so many men out on the front, women were called in to work in the factories, making shells, bullets, etc., as well as working on busses, trains, and all over the place. Women had been working in various jobs for a long time, of course, including in factories, but this gave them employment in sectors that had hitherto normally held been by men. The campaigners for female suffrage agreed to down their placards and join in the war effort, but once piece was signed, they picked them right back up again.

Universal suffrage for all men and women over the age of 21, unless disqualified on grounds of being mentally ill, imprisoned or a sitting member of the House of Lords, was established in 1919, just in time for the election; it also allowed them to stand for election. Women had the right to vote (and stand for election) in municipal and local elections for decades, but this was the first time they had the right to vote in national elections. The legislation also allowed women to vote in Irish regional and home-rule elections on the same basis as men[1].

The original Tory leader of the War Coalition, Edward Mitchell, was forced to stand down due to his health in 1916, and he wouldn’t return to frontline politics for several more years until he recovered. In his place, the leader of the Coalition Liberals, Austen Chamberlain, was quickly shunted into the PM’s seat, where he would remain until the 1919 election.

And, boy, was that an election. The so-called “Peace Coalition”, which had formed the opposition during the war, had campaigned hard, on the basis that the government had not only dragged the country into a pointless and bloody conflict, where Britain had ended up on the losing side. On the other hand, the members of the War Coalition had campaigned against the Opposition, decrying their lack of support in a war against the formation of a continental hegemon.

Other, newly fledged parties campaigned in this election, which saw an unprecedented number of people eligible to vote in it. Defeat had shaken the consciousness of Britain hard, and also saw several hard-line candidates on both extremes of the political spectrum get considerable support. However, the intricacies of STV mitigated much of that, but they would still win seats in local elections, which in Great Britain still used FPTP, or the bloc vote.

In the end, the War Coalition, with a few new faces, and dropping a few old ones, won out, but with a majority that was cut nearly in half. The new leader of the Conservatives, Grenville Baldwin[2], became the new PM.

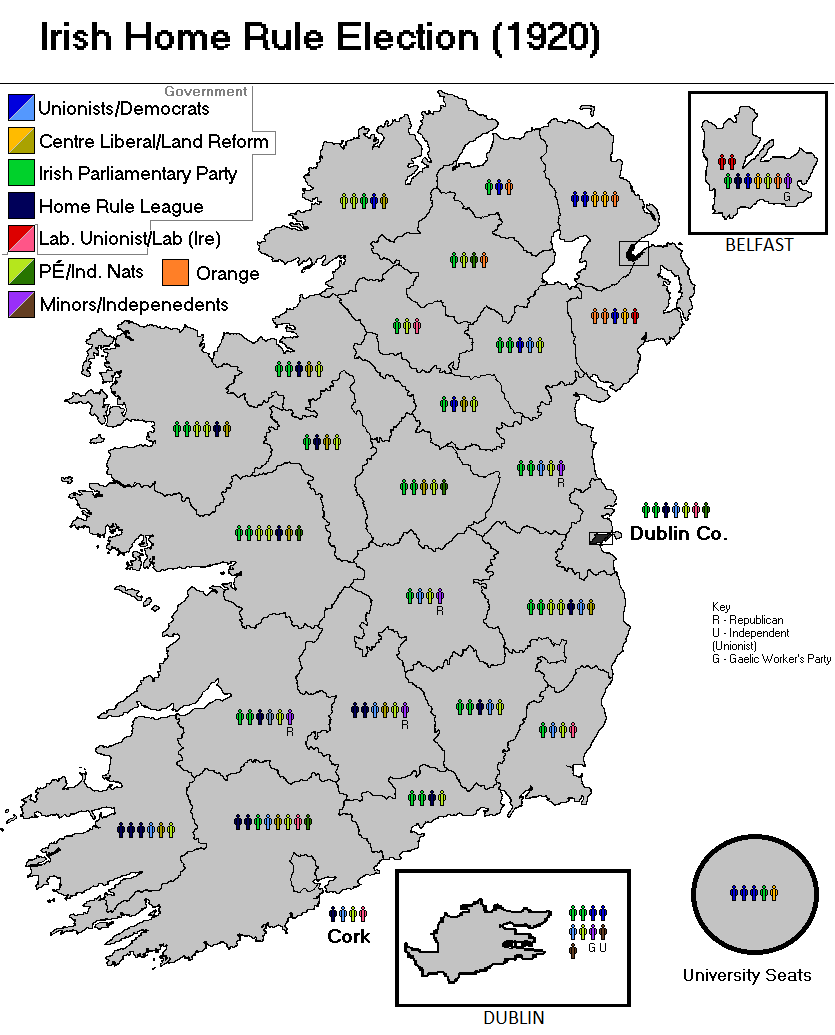

The Irish home rule election, held the following year, had a similar theme. The old coalition held on, though surprisingly with a bigger effective majority than they started with, thanks to support from several new parties.

*

Result of the 1919 Westminster election

HM’s Government (386), of which

Also, HMG’s supporters (28), of which

HM’s Loyal Opposition (207), of which

Other opposition parties

Result of the 1920 Irish Assembly election

HM’s Government (75), of which

Also, HMG’s supporters (24), of which

Official Opposition (33), of which

Other opposition parties

Most of the industries and services that were brought under effective state control were returned to their previous owners. However, the matter of the railway network was of considerable controversy. Many MPs, especially those in the Labour Party, wanted to nationalise the whole system, as had been done in most other European countries. The Tories, along with enough of the Liberals, had other plans however.

There had been calls to merge and rationalise Britain’s railway companies since the 19th century, but little had come of it until now. The only question was how it was to be done.

With Ireland’s railways, there was a choice between three medium-sized groupings, or a single one that covered the entire country. In the end, the latter was agreed upon in the Railways (Ireland) Act 1922, which also transferred government oversight to Dublin. The Irish railways would be nationalised by the home-rule government in 1927, which was allowed for in the 1922 Act.

Meanwhile, the railways in Great Britain were a little more complicated. Several options were mooted. These ranged from one single, nation-wide grouping such as in Ireland, suggested by a handful of opposition Labour MPs, to as many as eight[13].

Eventually, it was agreed that there would be one single grouping for Scotland, with five in England and Wales, which came into force in the Railways (Grouping) Act (1923). A few small companies (mostly those not using standard gauge, or in remote areas) would remain outside these groupings. The new railway companies, or “groupings”, were:

Annoyed that they couldn’t get a nationalised railway system, many, including Labour MPs, tried to get worker participation onto the respective boards of directors for each company, but this was shot down by MPs sympathetic to the railway companies. Instead, there were to be negotiating mechanisms between employee representatives and the directors[15].

*

Radio broadcasting, once done by a number of private firms, was placed under a national monopoly in 1921, under the British Broadcasting Service[16] in Great Britain, and the Irish Broadcasting Service[17] in Ireland. These would later have monopoly over television broadcasts for some time.

IBS came under the authority of the Irish postal ministry[18]. At the insistence of the Irish nationalists, broadcasts were to be made in both English and Gaelic, though the latter was only really listened to in the west of Ireland (where the majority of the Gaelic speakers lived) or by the more romantic nationalists, which had mostly taught themselves.

*

Many promises had been made by HMG in order to keep the war effort running. Some, particularly amongst the Tories, had reservations about keeping them, but the rest of the government held their feet against the fire – sometimes with the help of the opposition as well.

With East Africa becoming a dominion in 1917, there came a push to integrate other British colonies in that area to it, similarly to how things were going in South Africa. In the East Africa Act (1925), Wituland, Uganda, the Rift Valley petty kingdoms and Equatoria were all incorporated into the dominion – as three provinces in Equatoria’s case.

Partially this was because the country was effectively bust – the cost of the war had strained Britain’s economy nearly to breaking point, and it couldn’t afford a muscularly imperial policy any longer. Labour and the other left-wing parties particularly supported a retreat from empire, and were in favour of building a country that wasn’t dependent on colonies for prestige or as a beholden market.

However this was also because Britain wanted to keep the Empire together, but in a different form. The Tories largely wanted the former, to try and maintain Britain’s position as a leading power – which it was, despite being defeated. The Liberals, mindful of the on-going turmoil in the rest of the world, also wanted to maintain the empire, but as a looser, more self-governing empire, to forestall the threat of gently simmering unrest boiling over into something much worse[19].

*

The Suspensory Act (1915) had held up the prospect of home-rule for Scotland (and indeed the rest of Britain) until after the war ended. Joseph Chamberlain’s call of “home rule for all” would have to wait some time to come to full fruition, but the provisions of the Home Rule (Scotland) Act 1915 came into force in 1919, as agreed.

The Scottish Assembly had 73 seats, with the same boundaries as those for the Westminster, and elected by STV. The constituencies were as follows:

It also had limited powers to propose its own measures to the Secretary of State, who could then chose to approve, reject, or amend them; any amended document would then have to go back to the Assembly for final approval.

However, in terms of matters of justice, the Assembly could only scrutinise decisions, and require the Secretary to justify them – it had no power to reject any of these measures.

*

Result of the 1920 Scottish Assembly election

Proportional representation was becoming increasingly popular amongst some of the states of Europe and abroad. Scandinavia and the Low Countries used the D’Hondt system, usually after implementing universal suffrage. However, in the UK, as well as elsewhere in the Empire, the use of the single transferable vote was becoming very much the thing.

Aside from Britain, Australia was one of the most enthusiastic early-adopters of the system. By 1919, it was being used in the municipal elections of every state capital city, as well as several local elections. It took a little longer for it to be adopted in the states’ legislatures, but they too all followed suit – Tasmania had already done so in 1903, and was joined by Victoria (1919), Queensland (1924), South Australia (1925), New South Wales (1927) and Western Australia (1934)[20]. It was first used to elect the territorial assembly of Northern Australia in 1946[21]. National elections for both the House of Representatives and Senate first used STV in 1916, partially to remove the spoiler effect of nascent parties[22]. Compulsory voting was mooted several times during the 1910s and 20s, to combat low turnout, but it was not put into statute until 1927[23], but it was not required that candidates put down fully exhaustive lists of preferences[24].

The Australians also pioneered so-called “group tickets”, for elections to first the Senate[25] and later to the House of Representatives. This system groups candidates together by party, and allows voters to apportion preferences either to single parties, or otherwise to specific candidates of that party, though not both for the same party. Eventually, this would be adopted in several other parts of the Empire/Commonwealth, particularly as colonies gained their independence.

New Zealand also started using STV for national elections in 1928, and in local government in 1936[26]. The Canadian provinces of *Alberta and *Manitoba began using STV in provincial elections during the 1920s[27], which was eventually adopted throughout both state’s ridings (constituencies), as well as municipal elections in Vancouver starting in 1929.

*

The establishment of the Dominion of East Africa increased pressure to grant Home Rule to India. Many from the nascent middle class had formed associations to pursue this, either on a regional or pan-Indian basis, and had insisted on concessions in exchange for helping recruitment. With the war turning desperate, the government in Westminster made promises for this to be brought forwards once peace had been signed.

The Tories may have been annoyed about expanding the vote to women, but the matter of India was a whole other ballgame. The Liberals and left-wing parties, both inside the coalition and in opposition, along with a few moderate Conservatives, managed to overrule the ones that refused to budge. Eventually a timetable was agreed to, and a mammoth piece of legislation, though it needed the use of the Parliament Act to get it past the Lords, who were absolutely resolute in voting it down. India was to get home rule, and achieved it in August 1925. First came the district elections, then the provincial ones, and finally the national ones.

Due to the highly complex nature of Indian society, a rather convoluted system was developed, which included:

For now, the subcontinent was content. But it would not stay that way for much longer…

--

[1] This is even broader than the OTL Representation of the People Act (1918), were women had to be over 30 to vote, and they were still subject to property qualifications or had to be graduates of UK universities. IOTL, they wouldn’t be allowed to vote on an equal basis to men until 1928 in the UK. The Irish Free State allowed universal suffrage in 1922 IOTL.

[2] An ATL cousin of OTL’s Stanley Baldwin.

[3] Sort of equivalent to the OTL National Democratic Labour Party, but with a different origin. It is comprised of more centre-left leaning members of various socialist groups, who have banded together to support the National government, but with no intention of joining either faction of the Labour Party proper (for now). As mentioned in an earlier update – the left of British politics is heavily splintered ITTL.

[4] The Party of Ireland. The Irish Nationalists have come together in a new party, which is more or less equivalent to the SNP of OTL. There is no Sinn Fein ITTL, though the Irish Republican movement is still alive, if rather splintered.

[5] More or less equivalent to the OTL Silver Badge Party. Its platform (for the time being, at least) is pro-veteran’s rights, though it has rather more nationalism than its OTL counterpart.

[6] More of coalition really, comprised of various stripes of hard left and outright Marxist types.

[7] By now, the Liberal Unionists in Ireland have merged wholesale into the Unionist Party.

[8] The Liberals are attempting a rebrand, in order to attract a broader range of voters (i.e. more Catholics).

[9] A home-grown right-wing party, part of the trend in the maturation (or normalisation, if you prefer) of Irish politics, focusing more on the actual business of governing than griping over how much autonomy is enough. Pro-Home Rule (or at least not pro-Independence), and intended to appeal broadly to Catholics. It is more concerned with domestic issues, however, as opposed to being fixated on the question of Home Rule vs. Independence, which is surprisingly a popular position now that Home Rule has been dealt with.

[10] The closest OTL equivalent would probably be the OTL Farmer’s Party, who won seats in the Dail between 1922 and 1932. Basically, a home-grown left-wing party in favour of (surprise, surprise) land reform and the rights of small landholders.

[11] Established by the Orange Order, because the protestant Unionist Party wasn’t (a) protestant or (b) unionist enough . More or less equivalent to the OTL Liverpool Protestant Party.

. More or less equivalent to the OTL Liverpool Protestant Party.

[12] A hard-left/communist(ish) party, not unlike the Action Party, listed above. They don’t take their seats for similar reasons to the Republicans, though they (of course) also oppose the Imperialist Capitalist Government(TM).

[13] IOTL, the then Minister of Transport, Eric Campbell Geddes proposed 5 English groups (Southern, Western, North Western, Eastern and North Eastern), a group for passengers in London and separate single groupings for Scotland and Ireland. Eventually, though four groupings are created – London, Midland and Scottish Railway (which ran most of Scotland’s railways), London and North Eastern Railways (which ran all the way to Edinburgh), Great Western Railway and Southern Railway.

[14] About eight years sooner than its OTL equivalent.

[15] Equivalent to the BBC, and brought about under similar circumstances.

[16] Equivalent to Raidió Teilifís Éireann, the Irish public broadcaster. Ireland would get regular television much sooner than OTL, which was in 1960.

[17] As RTE did IOTL.

[18] This was true for OTL, as well.

[19] More on this later.

[20] IOTL Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory only use STV in their lower houses, whilst New South Wales, South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia all use STV in their upper houses. They use AV, called Instant-runoff in Australia, in the other house. (Queensland did away with its upper house entirely.)

[21] It uses AV IOTL, and only has a lower house.

[22] IOTL, it was established for similar reasons in 1918, though they used single-seat constituencies (i.e. AV) for the lower house. STV was for the HoR’s elections ITTL partially because of its use in the UK House of Commons elections.

[23] 1924 IOTL.

[24] Which is required for Senate elections by the present, IOTL.

[25] Also used IOTL.

[26] So far, New Zealand only uses STV in a few local elections and district health boards IOTL, though Christchurch City Council used it several times from 1917 to 1933.

[27] Also done IOTL, but on a smaller scale.

[28] Quite similar to the system used in India IOTL.

[29] Ditto.

[30] I learned this was used in IOTL from Malê Rising.

[31] There is no equivalent to the Statute of Westminster ITTL yet.

[32] The North-West Frontier Provinces, directly-controlled Baluchistan, Gilgit (an enclave within Kashmir) and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Chapter 8

In which is presented an overview of the United Kingdom after the war

The war had been hard for Britain, and its empire. Many millions of men (well, mostly men) of fighting age (and some too young or old) were sent out onto the battlefield. They came from all over the empire to fight for king and country. Some came back in one piece, other came back missing pieces. And all too many of them never came home at all, and are still lying in some foreign field that is forever [insert country of choice here].

Meanwhile, back in Britain, things weren’t easy either. With so many men out on the front, women were called in to work in the factories, making shells, bullets, etc., as well as working on busses, trains, and all over the place. Women had been working in various jobs for a long time, of course, including in factories, but this gave them employment in sectors that had hitherto normally held been by men. The campaigners for female suffrage agreed to down their placards and join in the war effort, but once piece was signed, they picked them right back up again.

Universal suffrage for all men and women over the age of 21, unless disqualified on grounds of being mentally ill, imprisoned or a sitting member of the House of Lords, was established in 1919, just in time for the election; it also allowed them to stand for election. Women had the right to vote (and stand for election) in municipal and local elections for decades, but this was the first time they had the right to vote in national elections. The legislation also allowed women to vote in Irish regional and home-rule elections on the same basis as men[1].

The original Tory leader of the War Coalition, Edward Mitchell, was forced to stand down due to his health in 1916, and he wouldn’t return to frontline politics for several more years until he recovered. In his place, the leader of the Coalition Liberals, Austen Chamberlain, was quickly shunted into the PM’s seat, where he would remain until the 1919 election.

And, boy, was that an election. The so-called “Peace Coalition”, which had formed the opposition during the war, had campaigned hard, on the basis that the government had not only dragged the country into a pointless and bloody conflict, where Britain had ended up on the losing side. On the other hand, the members of the War Coalition had campaigned against the Opposition, decrying their lack of support in a war against the formation of a continental hegemon.

Other, newly fledged parties campaigned in this election, which saw an unprecedented number of people eligible to vote in it. Defeat had shaken the consciousness of Britain hard, and also saw several hard-line candidates on both extremes of the political spectrum get considerable support. However, the intricacies of STV mitigated much of that, but they would still win seats in local elections, which in Great Britain still used FPTP, or the bloc vote.

In the end, the War Coalition, with a few new faces, and dropping a few old ones, won out, but with a majority that was cut nearly in half. The new leader of the Conservatives, Grenville Baldwin[2], became the new PM.

The Irish home rule election, held the following year, had a similar theme. The old coalition held on, though surprisingly with a bigger effective majority than they started with, thanks to support from several new parties.

*

Result of the 1919 Westminster election

HM’s Government (386), of which

- Conservative Party – 169

- Liberal (coalition) – 104

- Labour (coalition) – 50

- Labour Unionist – 5

- Irish Unionist – 8

- National Democratic Labour[3] – 25

Also, HMG’s supporters (28), of which

- Irish Parliamentary Party – 18

- Home Rule League – 10

HM’s Loyal Opposition (207), of which

- Labour Party – 58

- Liberal Party – 56

- Independent Labour Party – 27

- Cooperative Party – 31

- Social Democratic Federation – 35

Other opposition parties

- Paírtí Éirean[4] – 9 (mostly abstainers)

- National Party[5] – 20

- Action Party[6] – 15

- Independents and other minor parties – 7

Result of the 1920 Irish Assembly election

HM’s Government (75), of which

- Irish Parliamentary Party – 35

- Home Rule League – 18

- Unionist Party[7] – 13

- Centre Liberal[8] – 5

- Labour Unionist – 3

- Independent (Unionist) – 1

Also, HMG’s supporters (24), of which

- Democratic Party[9]

- Land Reform Party[10]

Official Opposition (33), of which

- Paírtí Éirean – 28

- Independent (Nationalist) – 5

Other opposition parties

- Labour Party (Irish) – 5

- Orange Party[11] – 6

- Irish Republicans – 4 (did not take seats)

- Gaelic Worker’s Party[12] – 2 (did not take seats)

- Independents – 1

Most of the industries and services that were brought under effective state control were returned to their previous owners. However, the matter of the railway network was of considerable controversy. Many MPs, especially those in the Labour Party, wanted to nationalise the whole system, as had been done in most other European countries. The Tories, along with enough of the Liberals, had other plans however.

There had been calls to merge and rationalise Britain’s railway companies since the 19th century, but little had come of it until now. The only question was how it was to be done.

With Ireland’s railways, there was a choice between three medium-sized groupings, or a single one that covered the entire country. In the end, the latter was agreed upon in the Railways (Ireland) Act 1922, which also transferred government oversight to Dublin. The Irish railways would be nationalised by the home-rule government in 1927, which was allowed for in the 1922 Act.

Meanwhile, the railways in Great Britain were a little more complicated. Several options were mooted. These ranged from one single, nation-wide grouping such as in Ireland, suggested by a handful of opposition Labour MPs, to as many as eight[13].

Eventually, it was agreed that there would be one single grouping for Scotland, with five in England and Wales, which came into force in the Railways (Grouping) Act (1923). A few small companies (mostly those not using standard gauge, or in remote areas) would remain outside these groupings. The new railway companies, or “groupings”, were:

- Caledonian Railways – covering all of Scotland

- Eastern Railways [think the Eastern region of British Rail IOTL]

- London-Midland Railways [The same as OTL, south of Scotland]

- North Eastern Railways [think the North Eastern region of British Rail IOTL]

- Southern Railways [The same as OTL]

- Western Railways [The same as GWR in OTL]

Annoyed that they couldn’t get a nationalised railway system, many, including Labour MPs, tried to get worker participation onto the respective boards of directors for each company, but this was shot down by MPs sympathetic to the railway companies. Instead, there were to be negotiating mechanisms between employee representatives and the directors[15].

*

Radio broadcasting, once done by a number of private firms, was placed under a national monopoly in 1921, under the British Broadcasting Service[16] in Great Britain, and the Irish Broadcasting Service[17] in Ireland. These would later have monopoly over television broadcasts for some time.

IBS came under the authority of the Irish postal ministry[18]. At the insistence of the Irish nationalists, broadcasts were to be made in both English and Gaelic, though the latter was only really listened to in the west of Ireland (where the majority of the Gaelic speakers lived) or by the more romantic nationalists, which had mostly taught themselves.

*

Many promises had been made by HMG in order to keep the war effort running. Some, particularly amongst the Tories, had reservations about keeping them, but the rest of the government held their feet against the fire – sometimes with the help of the opposition as well.

With East Africa becoming a dominion in 1917, there came a push to integrate other British colonies in that area to it, similarly to how things were going in South Africa. In the East Africa Act (1925), Wituland, Uganda, the Rift Valley petty kingdoms and Equatoria were all incorporated into the dominion – as three provinces in Equatoria’s case.

Partially this was because the country was effectively bust – the cost of the war had strained Britain’s economy nearly to breaking point, and it couldn’t afford a muscularly imperial policy any longer. Labour and the other left-wing parties particularly supported a retreat from empire, and were in favour of building a country that wasn’t dependent on colonies for prestige or as a beholden market.

However this was also because Britain wanted to keep the Empire together, but in a different form. The Tories largely wanted the former, to try and maintain Britain’s position as a leading power – which it was, despite being defeated. The Liberals, mindful of the on-going turmoil in the rest of the world, also wanted to maintain the empire, but as a looser, more self-governing empire, to forestall the threat of gently simmering unrest boiling over into something much worse[19].

*

The Suspensory Act (1915) had held up the prospect of home-rule for Scotland (and indeed the rest of Britain) until after the war ended. Joseph Chamberlain’s call of “home rule for all” would have to wait some time to come to full fruition, but the provisions of the Home Rule (Scotland) Act 1915 came into force in 1919, as agreed.

The Scottish Assembly had 73 seats, with the same boundaries as those for the Westminster, and elected by STV. The constituencies were as follows:

- Aberdeen – 2-seat constituency

- Borders and Lothian – 6-seat constituency

- Clydeside, Stirling, Dumbarton and Falkirk DBs – 6-seat constituency

- Dundee – 2-seat constituency

- Edinburgh – 5-seat constituency

- Fife and Kirkcaldy DB – 3-seat constituency

- Forfar, Perth and Montrose DB – 4-seat constituency

- Galloway – 2-seat constituency

- Glasgow – 15-seat constituency

- Grampian – 5-seat constituency

- Highlands – 4-seat constituency

- Lanarkshire – 7-seat constituency

- Orkney and Shetland – single-seat constituency

- Southwest Scotland and Ayr DB – 8-seat constituency

- Scottish Universities – 3-seat constituency

It also had limited powers to propose its own measures to the Secretary of State, who could then chose to approve, reject, or amend them; any amended document would then have to go back to the Assembly for final approval.

However, in terms of matters of justice, the Assembly could only scrutinise decisions, and require the Secretary to justify them – it had no power to reject any of these measures.

*

Result of the 1920 Scottish Assembly election

- Conservative Party – 23 seats

- Liberal Party – 26 seats

- Labour Party – 12 seats

- Independent Labour Party – 2 seats

- Cooperative Party – 3 seats

- National Party – 1 seat

- Social Democratic Party – 4 seats

- Action Party – 2 seats

Proportional representation was becoming increasingly popular amongst some of the states of Europe and abroad. Scandinavia and the Low Countries used the D’Hondt system, usually after implementing universal suffrage. However, in the UK, as well as elsewhere in the Empire, the use of the single transferable vote was becoming very much the thing.

Aside from Britain, Australia was one of the most enthusiastic early-adopters of the system. By 1919, it was being used in the municipal elections of every state capital city, as well as several local elections. It took a little longer for it to be adopted in the states’ legislatures, but they too all followed suit – Tasmania had already done so in 1903, and was joined by Victoria (1919), Queensland (1924), South Australia (1925), New South Wales (1927) and Western Australia (1934)[20]. It was first used to elect the territorial assembly of Northern Australia in 1946[21]. National elections for both the House of Representatives and Senate first used STV in 1916, partially to remove the spoiler effect of nascent parties[22]. Compulsory voting was mooted several times during the 1910s and 20s, to combat low turnout, but it was not put into statute until 1927[23], but it was not required that candidates put down fully exhaustive lists of preferences[24].

The Australians also pioneered so-called “group tickets”, for elections to first the Senate[25] and later to the House of Representatives. This system groups candidates together by party, and allows voters to apportion preferences either to single parties, or otherwise to specific candidates of that party, though not both for the same party. Eventually, this would be adopted in several other parts of the Empire/Commonwealth, particularly as colonies gained their independence.

New Zealand also started using STV for national elections in 1928, and in local government in 1936[26]. The Canadian provinces of *Alberta and *Manitoba began using STV in provincial elections during the 1920s[27], which was eventually adopted throughout both state’s ridings (constituencies), as well as municipal elections in Vancouver starting in 1929.

*

The establishment of the Dominion of East Africa increased pressure to grant Home Rule to India. Many from the nascent middle class had formed associations to pursue this, either on a regional or pan-Indian basis, and had insisted on concessions in exchange for helping recruitment. With the war turning desperate, the government in Westminster made promises for this to be brought forwards once peace had been signed.

The Tories may have been annoyed about expanding the vote to women, but the matter of India was a whole other ballgame. The Liberals and left-wing parties, both inside the coalition and in opposition, along with a few moderate Conservatives, managed to overrule the ones that refused to budge. Eventually a timetable was agreed to, and a mammoth piece of legislation, though it needed the use of the Parliament Act to get it past the Lords, who were absolutely resolute in voting it down. India was to get home rule, and achieved it in August 1925. First came the district elections, then the provincial ones, and finally the national ones.

Due to the highly complex nature of Indian society, a rather convoluted system was developed, which included:

- Elections using STV throughout, under the Australian-style “group ticket” system

- Constituencies with a large number of seats, so that candidates from religious minorities within those areas would have a decent chance of getting elected

- Scheduled seats for certain small tribes, and for the Anglo-Indian population[28]

- Scheduled seats for the untouchables, at the insistence of the British and non-Hindu politicians[29]

- Separate constituencies for female councillors and MPs[30], voted by women, to make sure that they made up at least a decent fraction of those elected

- A great deal of power being delegated to the provinces, creating a federal India. This was designed to placate the regionalist parties, at the expense of the (still rather small) pan-Indian groups

- The Princely States would be incorporated for purposes of defence and foreign policy (still technically subordinate to Westminster[31]), but would be internally self-governing

- An upper house was established, with members appointed from each of the provinces and territories[32], with each of the Maharajas being given the right to sit there, or appoint a deputy to sit in their place

- Burma was detached from India, and turned into a crown colony

For now, the subcontinent was content. But it would not stay that way for much longer…

--

[1] This is even broader than the OTL Representation of the People Act (1918), were women had to be over 30 to vote, and they were still subject to property qualifications or had to be graduates of UK universities. IOTL, they wouldn’t be allowed to vote on an equal basis to men until 1928 in the UK. The Irish Free State allowed universal suffrage in 1922 IOTL.

[2] An ATL cousin of OTL’s Stanley Baldwin.

[3] Sort of equivalent to the OTL National Democratic Labour Party, but with a different origin. It is comprised of more centre-left leaning members of various socialist groups, who have banded together to support the National government, but with no intention of joining either faction of the Labour Party proper (for now). As mentioned in an earlier update – the left of British politics is heavily splintered ITTL.

[4] The Party of Ireland. The Irish Nationalists have come together in a new party, which is more or less equivalent to the SNP of OTL. There is no Sinn Fein ITTL, though the Irish Republican movement is still alive, if rather splintered.

[5] More or less equivalent to the OTL Silver Badge Party. Its platform (for the time being, at least) is pro-veteran’s rights, though it has rather more nationalism than its OTL counterpart.

[6] More of coalition really, comprised of various stripes of hard left and outright Marxist types.

[7] By now, the Liberal Unionists in Ireland have merged wholesale into the Unionist Party.

[8] The Liberals are attempting a rebrand, in order to attract a broader range of voters (i.e. more Catholics).

[9] A home-grown right-wing party, part of the trend in the maturation (or normalisation, if you prefer) of Irish politics, focusing more on the actual business of governing than griping over how much autonomy is enough. Pro-Home Rule (or at least not pro-Independence), and intended to appeal broadly to Catholics. It is more concerned with domestic issues, however, as opposed to being fixated on the question of Home Rule vs. Independence, which is surprisingly a popular position now that Home Rule has been dealt with.

[10] The closest OTL equivalent would probably be the OTL Farmer’s Party, who won seats in the Dail between 1922 and 1932. Basically, a home-grown left-wing party in favour of (surprise, surprise) land reform and the rights of small landholders.

[11] Established by the Orange Order, because the protestant Unionist Party wasn’t (a) protestant or (b) unionist enough

[12] A hard-left/communist(ish) party, not unlike the Action Party, listed above. They don’t take their seats for similar reasons to the Republicans, though they (of course) also oppose the Imperialist Capitalist Government(TM).

[13] IOTL, the then Minister of Transport, Eric Campbell Geddes proposed 5 English groups (Southern, Western, North Western, Eastern and North Eastern), a group for passengers in London and separate single groupings for Scotland and Ireland. Eventually, though four groupings are created – London, Midland and Scottish Railway (which ran most of Scotland’s railways), London and North Eastern Railways (which ran all the way to Edinburgh), Great Western Railway and Southern Railway.

[14] About eight years sooner than its OTL equivalent.

[15] Equivalent to the BBC, and brought about under similar circumstances.

[16] Equivalent to Raidió Teilifís Éireann, the Irish public broadcaster. Ireland would get regular television much sooner than OTL, which was in 1960.

[17] As RTE did IOTL.

[18] This was true for OTL, as well.

[19] More on this later.

[20] IOTL Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory only use STV in their lower houses, whilst New South Wales, South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia all use STV in their upper houses. They use AV, called Instant-runoff in Australia, in the other house. (Queensland did away with its upper house entirely.)

[21] It uses AV IOTL, and only has a lower house.

[22] IOTL, it was established for similar reasons in 1918, though they used single-seat constituencies (i.e. AV) for the lower house. STV was for the HoR’s elections ITTL partially because of its use in the UK House of Commons elections.

[23] 1924 IOTL.

[24] Which is required for Senate elections by the present, IOTL.

[25] Also used IOTL.

[26] So far, New Zealand only uses STV in a few local elections and district health boards IOTL, though Christchurch City Council used it several times from 1917 to 1933.

[27] Also done IOTL, but on a smaller scale.

[28] Quite similar to the system used in India IOTL.

[29] Ditto.

[30] I learned this was used in IOTL from Malê Rising.

[31] There is no equivalent to the Statute of Westminster ITTL yet.

[32] The North-West Frontier Provinces, directly-controlled Baluchistan, Gilgit (an enclave within Kashmir) and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

And also the obligatory election map for the Irish home rule assembly (1920):

Any comments on my recent Irish Home Rule election map?

Is it too crazy? Do you want me to explain the parties a bit more?

Am I expanding STV too quickly?

All constructive criticism is welcome, chaps (and chapesses).

Is it too crazy? Do you want me to explain the parties a bit more?

Am I expanding STV too quickly?

All constructive criticism is welcome, chaps (and chapesses).

Sorry for not replying for ages - real life got in the way.

Not very much, to be honest. They'll reintegrate later on.

Oh, and the next update should be up soon, if I can decide on whether to post it as is or whether it needs another section.

What are the ideological differences between the Coalition and non-coalition parts of Labour and Liberal, apart from having supported (or not) the war?

Not very much, to be honest. They'll reintegrate later on.

Oh, and the next update should be up soon, if I can decide on whether to post it as is or whether it needs another section.

Chapter 9

In which we see Germany grow larger, and the formation of the League of Nations

The Great War took its toll on both victors and defeated alike. Though the Austrians were amongst the victors, they didn’t gain any territory. It did gain a sphere of influence in Eastern Europe (Poland), though it was shared with Germany[1].

Despite this, the costs incurred by the Empire were great, both in terms of men and hard cash. The minorities of the Empire were making increasing demands for autonomy, but no plan proposed by the Imperial government was acceptable to everyone.

Eventually, the Emperor Rudolf, who had succeeded his father in 1916, decided to put forwards his own plan in 1921. He would remain as emperor over the Habsburg domains, but several of his relatives would be installed as kings over the major parts of the empire. In this way, he hoped, that it would satisfy the more moderate nationalists, and keep the family holdings together at the same time.

Rudolf’s first cousin, Francis Ferdinand, was made king of Hungary, whilst another cousin, Charles Otto[2] became king of Bohemia. Rudolf’s eldest son (Francis Charles) was installed as King of Serbia, his second son (Otto[3]) as King of Croatia, and his third son (Francis Joseph) as King of Albania. Galicia was given to Charles Theodor, king of Poland. Rudolf would remain as Archduke of Austria proper.

In 1921, Luxembourg held a plebiscite on admittance to the German Empire, which was successful, with 79.3% of the vote. Accession was completed on 1st January 1922. Later that year, a similar vote was held in Austria and Liechtenstein, which won, though rather more narrowly – 55.6% and 61.3% respectively; the Austrian terms of accession allowed Rudolf to retain his title as Emperor of the Habsburg Realms, though he would be referred to as Archduke in his capacity as head of a German state. Finally, the German people would be united[4].

Unfortunately, the jubilation would not last long. The writing was on the wall for the old order in Germany…

*

The United States, being the only major power to have avoided fighting in the Great War, was deeply concerned about its effect on the world. Partially encouraged by the so-called Peace Party, President Jefferson Lowry[5] proposed the establishment of “A League of Nations, for the Preservation of World Peace”. This document formed the basis of what would become the League of Nations.

Lowry’s proposals included that the League would incorporate the Permanent Court of Arbitration, formed in 1896[6], take over control of internationalised areas (Shanghai, Tangier, the Bosporus), and form a Permanent Court of International Justice. In addition, there would be a League Council, with permanent members (the great powers of the day) and five non-permanent members (rotating, with three-year terms; one member to come from Europe, one from either Asia, Africa or the Pacific, and one from North or South America, with two more from any part of the world). The Permanent Council members could veto any decision, but this could be overturned by a two-thirds majority of the entire council.

President Lowry invited delegates from all independents states to attend the initial conference (1922) in New York. There was much speculation in the media as to which countries would attend, and which wouldn’t. The French government, for example, looked like it would boycott the conference when the Germans confirmed their attendance, though this turned out not to be the case.

Founding members of the League of Nations include the following:

The Permanent members of the League Council were France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States. The first non-permanent members were Argentina, Greece, Newfoundland, Siam, Sweden and Venezuela.

The first major case between countries before the League was an arbitration case between Sweden and Finland, over the Aaland Islands. They had come under Swedish occupation as a result of the Great War, which Finland disputed. However, the Finish military was not strong enough to dislodge them, and the Germans were not interested in intervening so soon after the war had ended, so, in 1922, Finland brings the case before the Court of Arbitration.

Eventually, the League decides that a referendum of the Islands’ people will resolve the matter, and the result of which will be binding on both parties, to be held the following year.

Sweden wins the referendum, with 79% in favour of remaining under its rule. However, the terms of the final agreement means that Aaland remains highly autonomous, that Finnish observers be allowed to visit the island for the next 30 years, and that the provisions of the Aaland Convention (1856) be upheld – the islands must remain unfortified.

--

[1] No prizes for guessing who had the biggest share.

[2] ATL half-brother to Emperor Karl.

[3] Who we last met in Chapter 6.

[4] Well, apart from those living in Bohemia. And Hungary. And everywhere else…

[5] ATL character.

[6] Equivalent to the OTL Permanent Court of Arbitration, formed in 1899.

In which we see Germany grow larger, and the formation of the League of Nations

The Great War took its toll on both victors and defeated alike. Though the Austrians were amongst the victors, they didn’t gain any territory. It did gain a sphere of influence in Eastern Europe (Poland), though it was shared with Germany[1].

Despite this, the costs incurred by the Empire were great, both in terms of men and hard cash. The minorities of the Empire were making increasing demands for autonomy, but no plan proposed by the Imperial government was acceptable to everyone.

Eventually, the Emperor Rudolf, who had succeeded his father in 1916, decided to put forwards his own plan in 1921. He would remain as emperor over the Habsburg domains, but several of his relatives would be installed as kings over the major parts of the empire. In this way, he hoped, that it would satisfy the more moderate nationalists, and keep the family holdings together at the same time.

Rudolf’s first cousin, Francis Ferdinand, was made king of Hungary, whilst another cousin, Charles Otto[2] became king of Bohemia. Rudolf’s eldest son (Francis Charles) was installed as King of Serbia, his second son (Otto[3]) as King of Croatia, and his third son (Francis Joseph) as King of Albania. Galicia was given to Charles Theodor, king of Poland. Rudolf would remain as Archduke of Austria proper.

In 1921, Luxembourg held a plebiscite on admittance to the German Empire, which was successful, with 79.3% of the vote. Accession was completed on 1st January 1922. Later that year, a similar vote was held in Austria and Liechtenstein, which won, though rather more narrowly – 55.6% and 61.3% respectively; the Austrian terms of accession allowed Rudolf to retain his title as Emperor of the Habsburg Realms, though he would be referred to as Archduke in his capacity as head of a German state. Finally, the German people would be united[4].

Unfortunately, the jubilation would not last long. The writing was on the wall for the old order in Germany…

*

The United States, being the only major power to have avoided fighting in the Great War, was deeply concerned about its effect on the world. Partially encouraged by the so-called Peace Party, President Jefferson Lowry[5] proposed the establishment of “A League of Nations, for the Preservation of World Peace”. This document formed the basis of what would become the League of Nations.

Lowry’s proposals included that the League would incorporate the Permanent Court of Arbitration, formed in 1896[6], take over control of internationalised areas (Shanghai, Tangier, the Bosporus), and form a Permanent Court of International Justice. In addition, there would be a League Council, with permanent members (the great powers of the day) and five non-permanent members (rotating, with three-year terms; one member to come from Europe, one from either Asia, Africa or the Pacific, and one from North or South America, with two more from any part of the world). The Permanent Council members could veto any decision, but this could be overturned by a two-thirds majority of the entire council.

President Lowry invited delegates from all independents states to attend the initial conference (1922) in New York. There was much speculation in the media as to which countries would attend, and which wouldn’t. The French government, for example, looked like it would boycott the conference when the Germans confirmed their attendance, though this turned out not to be the case.

Founding members of the League of Nations include the following:

Albania, Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Central America, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Denmark, East Africa, Ecuador, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Newfoundland, Norway, Paraguay, Persia, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Siam, South Africa, Sweden, the United Baltic Duchy, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uruguay, Venezuela

During the following three years, they would be joined by: Afghanistan, India, Nepal (all 1925), Guatemala (1926), Arabia, Bulgaria, Greece, Haiti, Mesopotamia, Nejd, Romania, Turkey and Yemen (all 1927).

The Permanent members of the League Council were France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States. The first non-permanent members were Argentina, Greece, Newfoundland, Siam, Sweden and Venezuela.

The first major case between countries before the League was an arbitration case between Sweden and Finland, over the Aaland Islands. They had come under Swedish occupation as a result of the Great War, which Finland disputed. However, the Finish military was not strong enough to dislodge them, and the Germans were not interested in intervening so soon after the war had ended, so, in 1922, Finland brings the case before the Court of Arbitration.

Eventually, the League decides that a referendum of the Islands’ people will resolve the matter, and the result of which will be binding on both parties, to be held the following year.

Sweden wins the referendum, with 79% in favour of remaining under its rule. However, the terms of the final agreement means that Aaland remains highly autonomous, that Finnish observers be allowed to visit the island for the next 30 years, and that the provisions of the Aaland Convention (1856) be upheld – the islands must remain unfortified.

--

[1] No prizes for guessing who had the biggest share.

[2] ATL half-brother to Emperor Karl.

[3] Who we last met in Chapter 6.

[4] Well, apart from those living in Bohemia. And Hungary. And everywhere else…

[5] ATL character.

[6] Equivalent to the OTL Permanent Court of Arbitration, formed in 1899.

And, what the heck, the next part is ready...

Chapter 10

In which the world economy shudders, and the major powers feel the strain

Defeat for the United Kingdom was a severe shock to the system. So many men lost, so much blood spilt, so much treasure spent, and for what?

That was a question many both in and out of British political circles. Yes, it had finished the war with more territory than it started, and had managed to curtail Germany’s more ambitious plans. But its centuries-long ambition, to prevent a single power from dominating the continent, had failed.

The British economy was shuddering. Huge numbers of factories had to be converted back from war work, and there were innumerable de-mobbed soldiers to deal with. Many wanted their old jobs back, to find that women had been doing them for years – and many of the women were reluctant to give them up.

Some of the more unlucky ones were traumatised for life. Some had lost limbs, some lost their vision or hearing. Some lost their confidence, and some lost their sanity…

The government was faced with a dire set of challenges. Medical examinations of the working-class men had shown just how poor their health was, especially the inner city boys[1]. Their diets were appalling, their living conditions unsanitary. They had been promised a home fit for heroes, but came back to more of the same.

The end of the war also meant the end of much-needed lines of credit from the major financial markets. The government had sold war bonds to its citizens, and raised taxes, now levied at a much wider range of people than before the war started. But it also borrowed in huge amounts, particularly from the Americans.

The Chancellor was forced to indulge in some financial jiggery-pokery in order to keep up with the interest payments. The war bonds were refinanced, so that they wouldn’t have to be paid back in full as long as they kept up with the interest[2]. Public spending was cut back, despite protestations, especially from the Labour Party.

The older warships were either scrapped or turned into target practice (if they were no longer repairable) or sold off (if they were). Aside from the newly-minted dominions, such as East Africa (and later India), the biggest buyers were in Latin America.

When back-pay to the soldiers was late, there was uproar in the press. When the police demanded better conditions, they went on strike – the government subsequently banned them from doing so[3]. As the economy contracted, jobs were cut or wages were cut. The unions became increasingly militant, and strike after strike hit the country even harder. Communists and Nationalists found themselves in the strange position of protesting with the same message – “The Government Has Failed”. This resonated with many, so much so that they won a lot of seats in the 1919 election, and did as well or better in the following one, in 1922.

*

Result of the 1922 Westminster election – the National Government

HM’s Government (425), of which

HM’s Loyal Opposition (108), of which

By this point, one of the major debates in Westminster was whether Britain could actually afford its empire. The Tories, unsurprisingly, denounced this with great vigour. Many in Labour and the other left-wing parties wanted rid of the old imperialist system altogether. The Liberals were wavering – they wanted to maintain as much of the empire as possible, but in a new relationship.

In 1923, Britain transferred its Solomon Islands colony to Australia, which incorporated it as a territory[5], whilst it gave its colony of Samoa to New Zealand. In 1925, India had become a dominion, whilst the British colonies of Wituland, Uganda, Equatoria, and the various Rift Valley protectorates, were given to East Africa. In 1928, South Africa was given Bechuanaland, Basutoland, Swaziland, Matabeleland and Mashonaland as integrated protectorates, and Zambezia[6] as a territory.

Aside from everything else, this was a huge cost-cutting exercise. With India now an independent country, it would be responsible for the upkeep of its own armed forces, and industrial development could be implemented thanks to British financing.

But Britain hadn’t just borrowed to keep itself afloat. Much of the money it borrowed from America was lent on to France and Russia, to help their war economies. Russia, with a lighter burden in terms of reparations, was (just) managing to keep up payments to Britain and to the Central Powers, though this was done on the backs of the Russian people.

France, on the other hand, was in a much tighter situation. Humiliated by military defeat, by territorial losses, and by a harsh peace settlement, their governments changed so often that they hardly knew if they were coming or going.

A militant right-wing party, Action Nationale, was becoming increasingly popular, gaining more and more seats with each fresh election. By 1924, they headed a governing coalition for the first time, and appointed their leader, Paul Marie Thomas, as president[7], and they passed legislation granting him sweeping powers.

At first, they stated that they were not willing to keep up their payments of reparations and their debt repayments, which made them popular with the exhausted French people. Now they were in power, Thomas declared that they would pay neither.

Defaulting on their loans to Britain caused the UK Treasury headaches, especially as they were counting on repayments from France to pay back its own debts to America. After some grovelling and not inconsiderable commercial concessions, particularly involving lowering tariffs on American goods, Washington agreed to reschedule the payments. France had secured its loans against shares in the Suez Canal, which ended up being taken by Britain – some of these were “gifted” to the US in exchange for offsetting them against the size of Britain’s debt.

Germany took the matter of reparations to the League of Nations court, but by then things were spiralling out of control for them as well.

The Reds were coming out of the woodwork…

--

[1] IOTL, this first came to light during the Boer War.

[2] This happened IOTL too, but rather later. With the US not in the war, the lines of credit from Washington were nowhere nearly as extensive.

[3] Something similar happened IOTL.

[4] Similar to the OTL party.

[5] Including the islands that were part of formerly German New Guinea.

[6] OTL South Rhodesia/Zimbabwe.

[7] The position of president was an appointed one in the Third Republic.

Chapter 10

In which the world economy shudders, and the major powers feel the strain

Defeat for the United Kingdom was a severe shock to the system. So many men lost, so much blood spilt, so much treasure spent, and for what?

That was a question many both in and out of British political circles. Yes, it had finished the war with more territory than it started, and had managed to curtail Germany’s more ambitious plans. But its centuries-long ambition, to prevent a single power from dominating the continent, had failed.

The British economy was shuddering. Huge numbers of factories had to be converted back from war work, and there were innumerable de-mobbed soldiers to deal with. Many wanted their old jobs back, to find that women had been doing them for years – and many of the women were reluctant to give them up.

Some of the more unlucky ones were traumatised for life. Some had lost limbs, some lost their vision or hearing. Some lost their confidence, and some lost their sanity…

The government was faced with a dire set of challenges. Medical examinations of the working-class men had shown just how poor their health was, especially the inner city boys[1]. Their diets were appalling, their living conditions unsanitary. They had been promised a home fit for heroes, but came back to more of the same.

The end of the war also meant the end of much-needed lines of credit from the major financial markets. The government had sold war bonds to its citizens, and raised taxes, now levied at a much wider range of people than before the war started. But it also borrowed in huge amounts, particularly from the Americans.

The Chancellor was forced to indulge in some financial jiggery-pokery in order to keep up with the interest payments. The war bonds were refinanced, so that they wouldn’t have to be paid back in full as long as they kept up with the interest[2]. Public spending was cut back, despite protestations, especially from the Labour Party.

The older warships were either scrapped or turned into target practice (if they were no longer repairable) or sold off (if they were). Aside from the newly-minted dominions, such as East Africa (and later India), the biggest buyers were in Latin America.

When back-pay to the soldiers was late, there was uproar in the press. When the police demanded better conditions, they went on strike – the government subsequently banned them from doing so[3]. As the economy contracted, jobs were cut or wages were cut. The unions became increasingly militant, and strike after strike hit the country even harder. Communists and Nationalists found themselves in the strange position of protesting with the same message – “The Government Has Failed”. This resonated with many, so much so that they won a lot of seats in the 1919 election, and did as well or better in the following one, in 1922.

*

Result of the 1922 Westminster election – the National Government

HM’s Government (425), of which

- Conservative Party – 163

- Liberal Party – 154

- Labour Party – 90

- Irish Unionist – 10

- Irish Labour Party – 5

- Labour Unionist – 3

- Irish Parliamentary Party – 17

- Home Rule League – 7

HM’s Loyal Opposition (108), of which

- Independent Labour Party – 47

- Cooperative Party – 36

- Social Democratic Federation – 25

- Action Party – 22

- National Party – 19

- Independent Conservative – 16

- Independent Liberal – 12

- Paírtí Éirean – 10

- Independents – 7

- Independent Communist – 2

- Scottish Prohibition Party[4] – 2

By this point, one of the major debates in Westminster was whether Britain could actually afford its empire. The Tories, unsurprisingly, denounced this with great vigour. Many in Labour and the other left-wing parties wanted rid of the old imperialist system altogether. The Liberals were wavering – they wanted to maintain as much of the empire as possible, but in a new relationship.

In 1923, Britain transferred its Solomon Islands colony to Australia, which incorporated it as a territory[5], whilst it gave its colony of Samoa to New Zealand. In 1925, India had become a dominion, whilst the British colonies of Wituland, Uganda, Equatoria, and the various Rift Valley protectorates, were given to East Africa. In 1928, South Africa was given Bechuanaland, Basutoland, Swaziland, Matabeleland and Mashonaland as integrated protectorates, and Zambezia[6] as a territory.

Aside from everything else, this was a huge cost-cutting exercise. With India now an independent country, it would be responsible for the upkeep of its own armed forces, and industrial development could be implemented thanks to British financing.

But Britain hadn’t just borrowed to keep itself afloat. Much of the money it borrowed from America was lent on to France and Russia, to help their war economies. Russia, with a lighter burden in terms of reparations, was (just) managing to keep up payments to Britain and to the Central Powers, though this was done on the backs of the Russian people.

France, on the other hand, was in a much tighter situation. Humiliated by military defeat, by territorial losses, and by a harsh peace settlement, their governments changed so often that they hardly knew if they were coming or going.

A militant right-wing party, Action Nationale, was becoming increasingly popular, gaining more and more seats with each fresh election. By 1924, they headed a governing coalition for the first time, and appointed their leader, Paul Marie Thomas, as president[7], and they passed legislation granting him sweeping powers.

At first, they stated that they were not willing to keep up their payments of reparations and their debt repayments, which made them popular with the exhausted French people. Now they were in power, Thomas declared that they would pay neither.

Defaulting on their loans to Britain caused the UK Treasury headaches, especially as they were counting on repayments from France to pay back its own debts to America. After some grovelling and not inconsiderable commercial concessions, particularly involving lowering tariffs on American goods, Washington agreed to reschedule the payments. France had secured its loans against shares in the Suez Canal, which ended up being taken by Britain – some of these were “gifted” to the US in exchange for offsetting them against the size of Britain’s debt.

Germany took the matter of reparations to the League of Nations court, but by then things were spiralling out of control for them as well.

The Reds were coming out of the woodwork…

--

[1] IOTL, this first came to light during the Boer War.

[2] This happened IOTL too, but rather later. With the US not in the war, the lines of credit from Washington were nowhere nearly as extensive.

[3] Something similar happened IOTL.

[4] Similar to the OTL party.

[5] Including the islands that were part of formerly German New Guinea.

[6] OTL South Rhodesia/Zimbabwe.

[7] The position of president was an appointed one in the Third Republic.

Last edited:

Share: