RECONSTRUCTION: THE SECOND AMERICAN REVOLUTION

The Sequel to Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid

By: Red_Galiray

"With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

The Sequel to Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid

By: Red_Galiray

"With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

Note: This story is a sequel to the timeline Until Every Drop of Blood is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War. The story only thread is available here. Given that it's a direct continuation, it's required to read that timeline first.

Chapter 1: The World the War Made

In April 1865, the United States successfully defeated the slaveholders’ rebellion by taking its capital, destroying its largest and most celebrated army, and then forcing the surrender or capturing the rest of its organized forces. But even if this was the end of the Confederate States and the American Civil War, it represented but a turning point in the on-going Second American Revolution and the start of the contentious Reconstruction Era. Winning the war had been possible only after a bloody struggle, but the Yankees who celebrated the end of the war and the freedmen who wept as they finally regained their liberty could hardly imagine that winning the ensuing “peace” would be just as difficult a contest. Marked by divisions, violence, and difficulty, the Reconstruction Era was also defined by the idealism of the victorious Revolutionaries, Black and White, who imagined that they could built a better nation, one that truly exemplified the national pledge of Liberty and Equality, on the ashes of the Old South. This optimism would be their guiding light in the great challenge that laid ahead.

Unlike what most Americans hoped, the defeat of Jackson and the death of Toombs did not bring about immediate peace and a settlement of the issues of the war. The armies had ceased to exist, but many rebels hadn’t laid down their arms yet; and although a stillness had returned to the battlefields, order and security hadn’t returned to the South, where famine, violence, and terrorism still raged on. While the supremacy and perpetuity of the Federal Union had been triumphantly established, the South and the nation as a whole remained in flux. A consensus on how to reconstruct the former Confederacy had not been reached, but Americans already knew that this Second American Revolution would remake the Southern States, and as such the end of the war represented but the beginning of a new process. The war had ended, but peace had not and could not come yet. Not when the South remained under anarchy, and millions of human beings under slavery.

Most common rebel soldiers, except for notorious war criminals, were allowed to return home. But acknowledging their defeat did not mean giving up their cause, much less accepting that they had been on the wrong. The great majority, especially those who had supported the Military Junta, still were fervent believers in White supremacy and slavery, and saw equality and emancipation as forced impositions they ought to resist. They were willing to concede that they could not overcome the Federal government by force of arms, but not that the cause of the Union was just or that it had a right to impose terms of peace over them. Some, in fact, did not even concede to the first point, maintaining the struggle as guerrillas despite their bleak odds of success. Even those who had seemingly accepted the reality of Yankee victory still wished to fight against the revolutionary tide, terrorizing or murdering Black freedmen and White Unionists.

Because “both the foundation of social relations (slavery) and the most recent structure of order and governance (the Confederacy) had almost simultaneously been destroyed,” writes historian Steven Hahn, “but no new social or political system had either quickly emerged or been imposed to replace them,” violence became endemic throughout the region. Especially because the famine and the Jacquerie were still on-going, meaning that in many localities the fight over land and food continued, with deadly consequences. “Cruel famine, bloody war, fratricide, and banditry,” were still “commonplace,” reported a man in the Virginia countryside. “We don’t mind Yankee bayonets if a piece of bread comes with them.” In fact, the surrenders only aggravated the problem. Those who had surrendered were usually given some meager provisions that were not enough for the long journey home; those that dispersed more irregularly, as a result of desertion for example, usually would have to find their own food. This mean “an inclination to robbery,” in the mild words of a Bureau agent, who recorded how “the provisions we give to the starving families are soon seized by the returning marauder.”

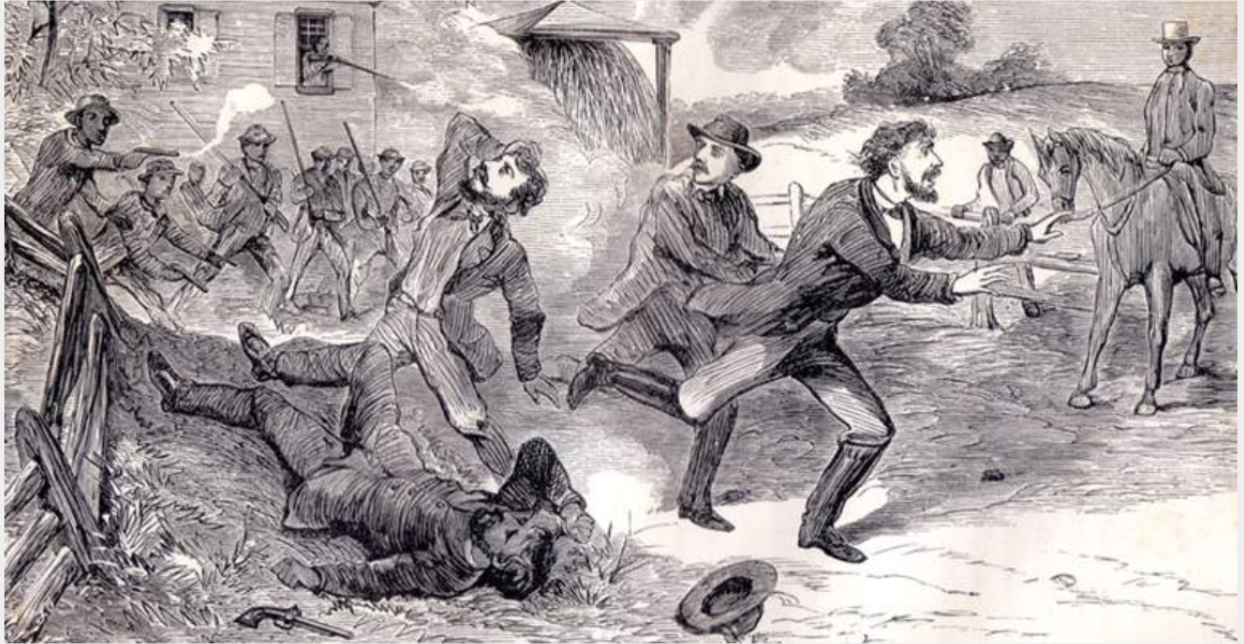

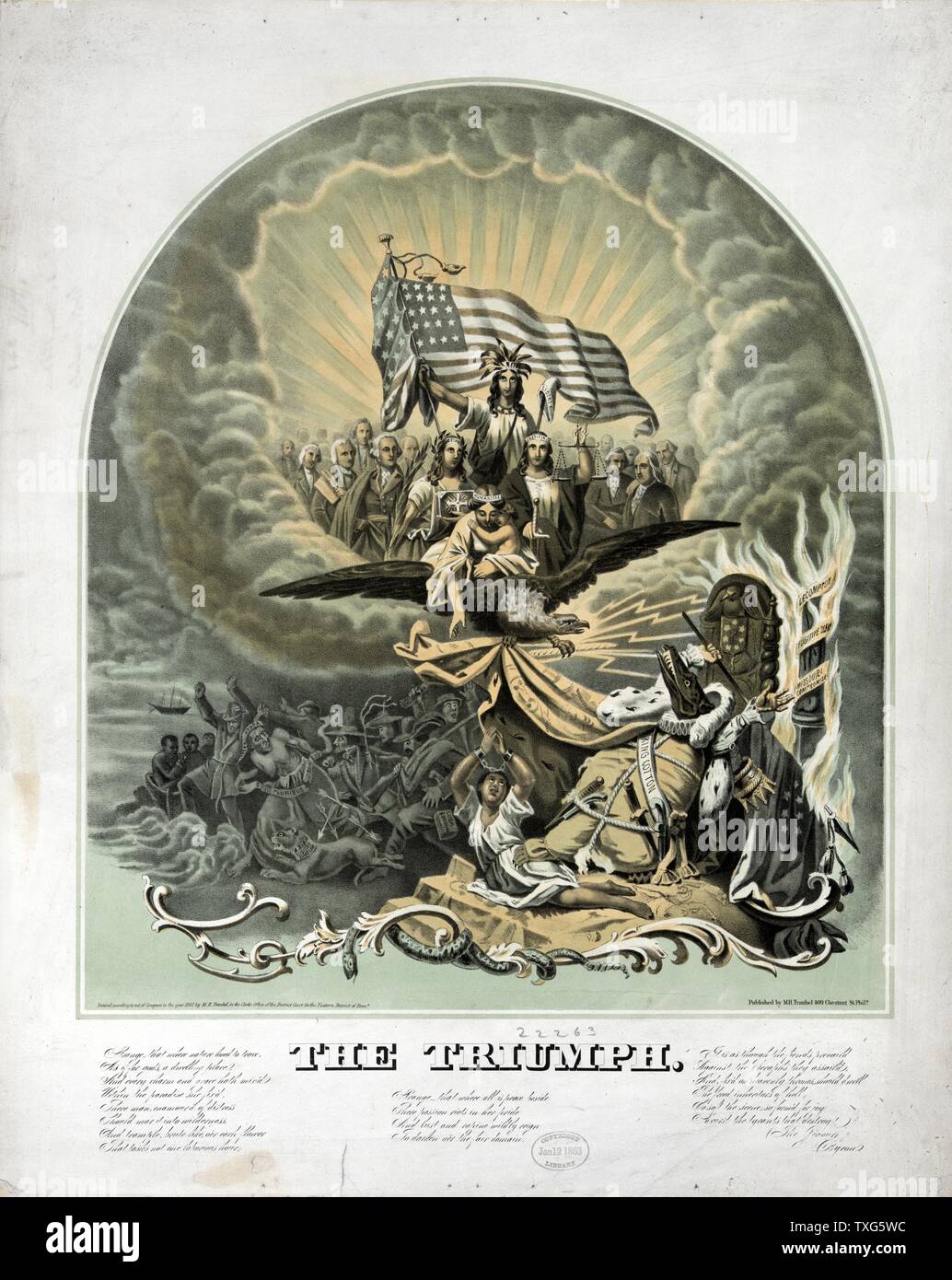

The Victory of the Union

But violence also took on a political angle. Unvanquished rebel guerrillas declared in many States that they would rather see “every nigger in a ditch than walking free,” attacking freedmen ruthlessly. A South Carolina guerrilla band under chieftain Dick Sims slaughtered many White men who took the oath of allegiance, while terrorists in the Black Belt pronounced land redistribution illegitimate and warned that “they would make their own laws . . . and if the negroes failed to hire and contract upon their terms before Christmas, or at that time, they would make the woods stink with their carcasses.” "Our negroes have . . . a tall fall ahead of them," a Mississippian said. “They will learn that freedom and independence are different things.” Because order could only be imposed by Federal soldiers, the areas they hadn’t reached yet devolved into a state of anarchy. In North Carolina, “they govern . . . by the pistol and the rifle;” in Arkansas, when Yankees finally reached a Black settlement near Pine Bluff they found “a sight that apald me 24 Negro men woman and children were hanging to trees all round the Cabbins.”

Everyday life in the South thus was affected by almost continuous violence. “Because so few individuals in the former Confederate states could claim secure standing in official political society, much of day-to-day life there became politicized,” explains Hahn. “With the old rules apparently obsolete and the new ones ill-prescribed, almost every act seemed to bear on the more general struggle over socially meaningful power.” With Confederate public authority destroyed and Federal authority not yet established, there were no rules or laws to effectively govern life, protect property, and punish injustice. “Every social bond had been ruptured,” grieved a Virginian. “All laws had become inoperative for want of officers to enforce them. All the safeguards of life, liberty and property had been uprooted.” Even in Union-occupied Savanah, residents denounced that “without civil government,” they were “exposed to repeated depredations and violence and . . . the peril of famine and anarchy.” In Jackson, within the guerrilla-infested Mississippi interior, civilians likewise clamored for US soldiers to arrive and “shoot the devils down where they can be found.”

How was this violence to be ended, order restored, and the Southern States reintegrated into the Union? The answer, for Northern and Southern reactionaries, was simple: turn power over to the men who had made and ruled the Confederacy. Beholden to strong traditions of White supremacy and local government, these men believed the Federal government had no right to impose laws on the conquered States, that Southern “outrages” would cease if Whites were allowed to reassert their control, and that including Black citizens in the body politic could only be the prelude to ignorant and corrupt “Negro domination.” No one articulated the point better than Robert J. Breckinridge, the uncle of the overthrown former Confederate President. While denouncing the “relentless military despotism” of the Southern Junta, Breckinridge warned Northerners not “to wound, to exasperate, to afflict, nor even to punish” the “deluded” Southern masses through such measures as confiscation and Black suffrage, but instead to “accept their restoration” with no great concession on their part except their military surrender.

This program of Restoration, rather than Reconstruction, would thus not greatly disturb Southern society. It would shield the former rebels from the consequences of their defeat by allowing them to maintain their local political power and force Black Americans into subordination. Its cornerstone was the offers by Southern State governments to allow rebel officeholders to retain their posts and to call the Confederate Legislatures into session in exchange of recognizing Federal authority. Lincoln had, in fact, seemed to toy with that very idea before. But this was as a concession in exchange of a surrender; now that the enemy had been destroyed, there was no need to compromise. And yet, several important men still argued against occupation, believed Reconstruction was both unpracticable and unwise, and thought the easiest way to restore order and governance was not through the Army, but by conciliating the elites of the old South.

The most salient example was General Sherman. While negotiating a surrender with General Johnston, Sherman had warned that not surrendering would be “to die in the last ditch and entail on his country an indefinite and prolonged military occupation.” Johnston had surrendered, so Sherman believed such an occupation was no longer needed nor desirable. Consequently, Sherman’s first arrangement was magnanimous. Assuring Johnston that Southerners would not be made “slaves to the people of the North,” Sherman offered to recognize the Confederate State governments, allow Southern soldiers to keep their arms and form militias to “preserve order,” and to offer a full pardon to every officer and official of the Confederacy, which would include the restoration of property. Sherman went as far as assuring Zebulon Vance that he’d keep his post as North Carolina Governor. Not a word was said about slavery. The US Army, Sherman believed, ought not to interfere with the inner politics of the Southern States, but allow local elites to retain their power. The Army simply could not reach and directly govern all the people in “all the recesses of their unhappy country,” and to try would result in “pure anarchy.” Sherman boasted that his arrangement would instead “produce Peace from the Potomac to the Rio Grande.”

The surrender of General Joe Johnston

The peace envisioned by Sherman was also the peace many Southerners were hoping for. Its terms were, as a matter of fact, essentially identical to the ones Breckinridge and Campbell had once sought. Yet, despite the coup and their ensuing catastrophic defeat, some Southerners still believed they could have a significant say in the post-war settlement, regulating Black labor and limiting their newfound freedom. “Political reconstruction might be unavoidable now,” Mary Greenhow Lee wrote, “but social reconstruction we . . . might prevent.” Some masters went as far as refusing to acknowledge the end of slavery. “To announce their freedom is not to make them free,” a general wrote ruefully. In Arkansas, a Bureau commissioner reported, “the freedmen are still treated as Slaves, the former slave owners in some cases proclaiming that ‘Slavery has not been abolished by any competent authority.’” Emancipation had been proclaimed, but it had yet to be enforced, and Southerners recognized that without Federal power they could yet cling to the remnants of the institution. Indeed, if control was turned over to the rebels, even the 13th amendment could be imperiled.

Even in areas where war-time emancipation had already virtually ended slavery, or where Reconstructed State governments under Lincoln had proclaimed its de jure end, it was clear that Southerners had not acquiesced to the full implications of Black freedom. In Alabama, planters “appeared disinclined to offer employment, except with guarantees that would practically reduce the Freedmen again to a state of bondage.” Supposedly loyal Mississippi planters, who had retained their lands by swearing loyalty to the government, still did not know "the first principles of a free-labor system" and believed "some compulsory system . . . indispensable," denounced a Bureau agent. In Tennessee, where the Brownlow constitution had already banned slavery, “regulators . . . are riding about whipping, maiming and killing all negroes who do not obey the orders of their former masters, just as if slavery existed.” In the so-called “Shermanland” settlements in South Carolina, former planters refused to recognize land redistribution, obtaining writs from rebel judges to expel Black landowners, and organizing militias to forcibly drive them away or force them to work.

All these measures were an example of the kind of peace settlement Southerners envisioned. If they could not have slavery, Bruce Levine writes, “Maybe a less complete form of servitude could be imposed—some form that, if not as satisfactory to them as old-South slavery, would still prove more profitable for employers than would genuinely free labor.” Some “system of serfdom,” in the words of James Appleton Blackshear; “things as they were, but perhaps under some other name,” in those of William J. Minor. Something that would, a Louisiana planter said, “keep ‘em as near a state of bondage as possible.” Even if freedom had to begrudgingly acknowledged, if allowed to “take charge of our affairs,” Southerners could still limit the freedmen’s rights, preventing them from moving freely, choosing and bargaining with employers, seeking legal redress, or have a say in government. This was the kind of settlement promised by Sherman’s peace cartel and the designs of Northern reactionaries, who preferred unjust peace by allowing White Southerners to subordinate the freedmen rather than a turbulent struggle to enforce Black rights against White violence.

But the Lincoln administration and the Northern people who had reelected him on the promise of Reconstructing the Union could not accept such a peace. In fact, when Grant read Sherman’s dispatch to the Cabinet, they were all astonished. An infuriated Stanton went as far as calling Sherman a traitor, something echoed by other Republican politicians. The fact that he had even thought to negotiate with a leader of the Confederate Junta was an especially “infamous outrage” to many. The Army and Navy Journal, which broadly reflected the opinions of Union soldiers, wrote sadly that Sherman “still stands, politically, where he did four years ago, untaught by events,” while the nation “has drifted forward, and he is left hopelessly in the rear.” Lincoln at once countermanded Sherman, sent Grant to conclude an unconditional surrender, and assured his Cabinet that “there is no authorized organ for us to treat with . . . We must simply begin with, and mould from, disorganized and discordant elements.” The government, in other words, would not recognize the rebel authorities.

As several Confederate Governors and Legislators were arrested and trialed over the next weeks, it became even clearer that the Lincoln administration was of “the opinion that no civil authority should be recognized which has its source in rebel election or appointment,” wrote Salmon P. Chase. Thus, the vision of a loyal but unreconstructed South was ended. Consequently, the South was to be declared a region without government, for the Confederacy and its States had been swept away. Unwilling to recognize the authority of the rebel officeholders, the US Army and the Bureaus all would have to take the tasks of governance upon themselves through military occupation, something unprecedented in American history and unconceivable in the antebellum. They would have to quell Southern violence, provide aid for the hungry, and pave the way for political reorganization. They would have to, as well, enforce the revolutionary laws and proclamation that resulted from the war, securing emancipation and defending civil rights. This would be the first step towards remaking the nation.

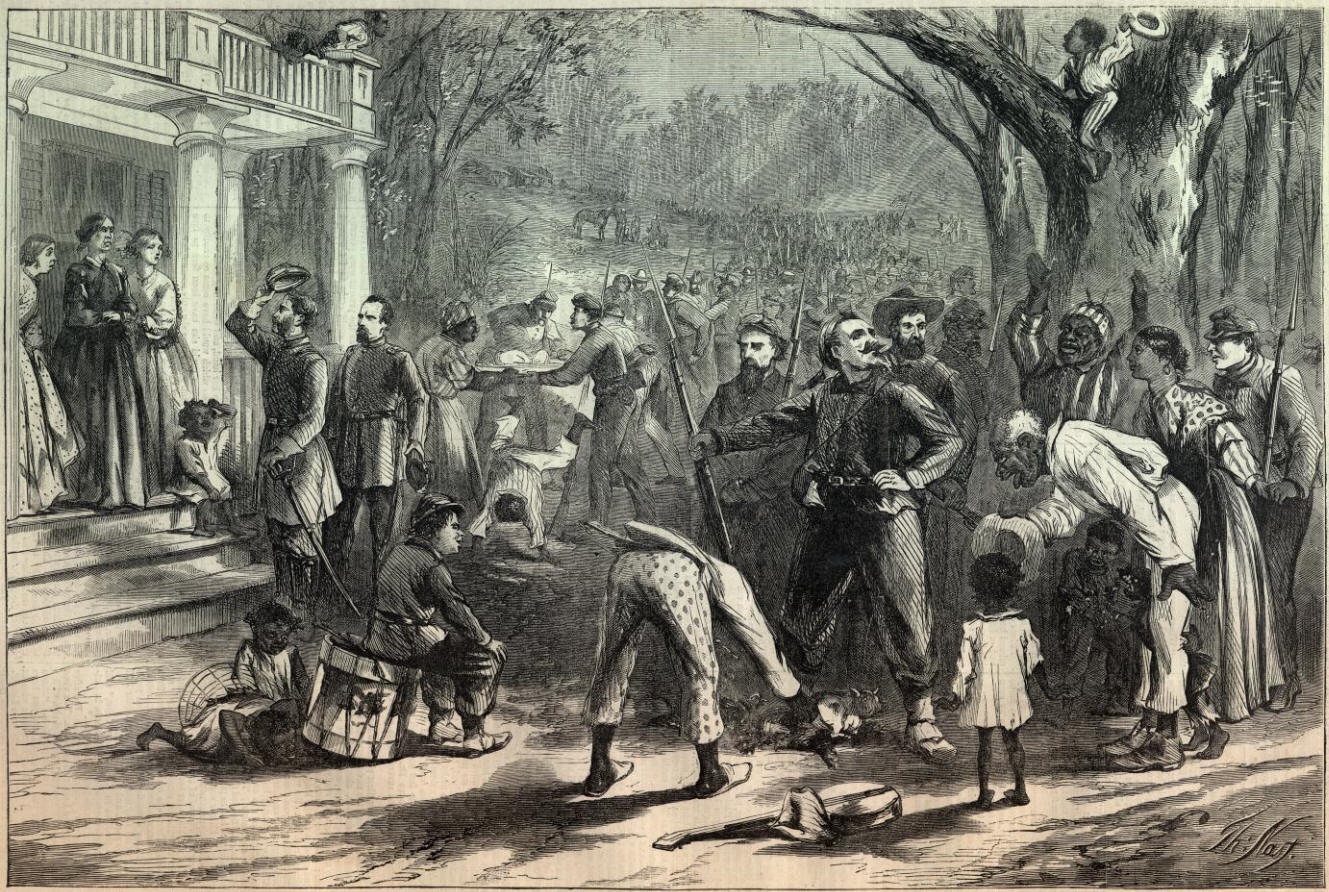

The Union Army transformed into an Army of Occupation

Within a famine-stricken South still in violent upheaval, only “the army of occupation” held power and could impose a measure of order. The commander over South Carolina, General Quincy Adams Gillmore, thus declared that “Lawlessness must be suppressed, industry encouraged, and confidence in the beneficence of the Government established,” by doling out rations and “hanging bandits, horse-thieves, and marauders . . . Wherever the authority of the United States exists there must exist protection for persons and property.” The end of the war in this way did not mean a retreat from the South, but rather the expansion of Army outposts to places that had not even seen a Yankee soldier during the conflict. “Slowly but surely, the military spread out toward regions far from the war’s front lines,” writes Gregory P. Downs. “From about 120 towns in March 1865, the army extended to 218 reported posts by the end of May and 334 by the end of August . . . People who had never seen a federal officer other than a postmaster suddenly found companies of troops in crossroads villages and county seats . . . making the army suddenly, shockingly present.”

The US Army, then, would be the enforcer of “peace and order” in the South, seeking to destroy the last remnants of the rebellion, suppress guerrillas, and defend civilians from violence. But it went farther than merely a police force, for the bluejackets also enforced the government’s revolutionary vision, redistributing land, arresting and judging traitors, and interfering directly in the Southern economy and society by regulating contracts and imposing new social rules. A judge who tried to overrule confiscation in Mississippi was promptly arrested by the military authorities for instance, while several North Carolina militiamen were hanged as war criminals for their actions against Western Unionists. Southern rebels had “lost their rights as citizens,” commanders warned, and as such they were subjected to martial law. A cousin of the exiled Commodore Maury bemoaned how the South “stands in the light of a conquered province and has no rights,” a sign of this oppression being how a friend had been arrested for hitting his former slave – something simply unthinkable in the antebellum.

The Second American Revolution would then go forward, with greater intensity and vigor after achieving military victory. The experiences and teachings of the long and bloody Civil War had convinced Northerners that this was the only way to truly secure the nation and its future prosperity and stability. The victory of Lincoln in the 1864 election, alongside the successful referendums on Black suffrage, also showed the commitment of the Northern people to Reconstruction and a new conception of Black people. As they saw Black soldiers taking a central role in many pivotal triumphs over the rebel armies, observed their self-reliance and hard work in redistributed land, and admired their drive for self-improvement and literacy, Northerners came to believe that Black people, freed from the fetters of slavery, could make the South flourish through free labor. The Philadelphia Inquirer declared that under free labor the South “will blossom like a rose, and her property will mount to an aggregate far exceeding the returns of the best days of the South, before the Rebellion paralyzed her industry, destroyed her resources, and enveloped her in the drapery of woe.” But this could only be if Black people were truly free, not only from slavery, but from violence, oppression, and discrimination.

The conditions in the South certainly demonstrated the need for continuous military intervention. Some believed, like Chase, that Southern Whites had been chastised by defeat and were ready to “accommodate themselves to any mode of reorganization the National Government may think best— even including the restoration to the blacks of the right of suffrage.” But other Northerners saw a South in active rebellion, “seething and boiling, as if a volcano were struggling beneath it.” Carl Schurz, during a Southern tour, reported “an utter absence of national feeling” and a “continuation of the war, not against the armed defenders of the Government, but against its unarmed friends.” The South “must be reconstructed, or rather constructed anew,” Schruz concluded, reflecting the prevailing Northern vision. “A free labor society must be established and built up on the ruins of the slave labor society . . . national control in the South must not cease until . . . free labor is fully developed and firmly established.” Officers on the field recommended at least three to five years of occupation; Thaddeus Stevens went as far as saying that it should continue until a new generation of Southerners was born to replace the old one and its devotion to the slave system.

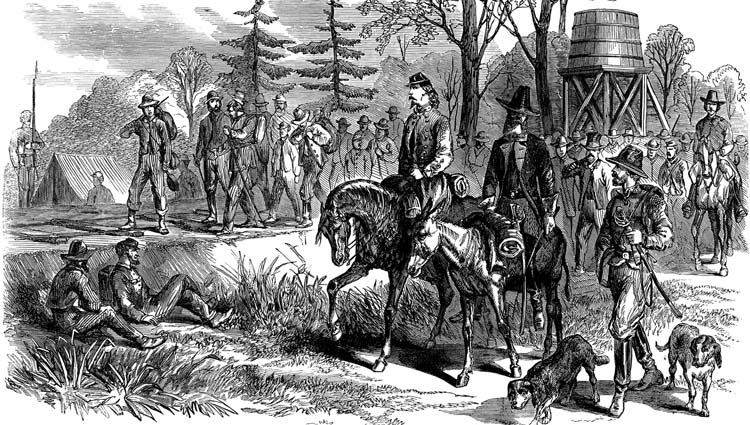

The Federal Government as the custodian of freedom and order in the post-war South

Faced with this situation, and despite misgivings over the nature of military rule, the constitutional justifications for Reconstruction, and how far these revolutionary changes should be pushed, Republicans stood united behind the goal of reconstructing the South. It is true that there still existed divisions between Moderates and Radicals, between the President and Congress. But overall, Abraham Lincoln and his Republican Party agreed on the necessity of transforming the South politically, socially, and economically. In the words of Senator William Pitt Fessenden, to not “yield the fruits of war” by turning power over to the same rebels they had been fighting, and to continue the occupation “until the civil authority of the government can be established firmly and upon a sure foundation.” To achieve this, they wished not merely to declare “parchment rights,” but to make them effective and offer loyalists real protection. Emancipation, James Garfield declared, could not be “a mere negation; the bare privilege of not being chained, bought, and sold, branded and scourged.” A Senator likewise said that “Southern legislators and people must learn, if they are compelled to learn by the bayonets of the Army of the United States, that the civil rights must and shall be respected.”

The instrument for compelling this respect would be the power of the National government. Embracing the greatly expanded National State, Republicans believed they had both the right and the duty to protect the rights of its citizens, even if this interfered with deeply rooted traditions of racism and local governance. “The prime issue of the war was between nationality one and indivisible, and the loose and changeable federation of independent States.” declared the aptly named The Nation. Union victory had in this regard marked “the consolidation of nationality under democratic forms . . . ratified by the blood of thousands of her sons.” This new American nation scarcely resembled its antebellum counterpart with its standing armies, national police force and bureaucracy, and expanded legal powers and constitutionally protected rights. “The youngest of us,” Wendell Phillips wrote, “are never again to see the republic in which we were born.” Nevertheless, these changes, astounding as they were, were here to stay, with the activist State only expanding, not retreating, in the face of famine, resistance, and violence.

By committing itself to this revolutionary path, the US government opened new possibilities to those who had been traditionally excluded from Southern power. One of these groups were Southern Unionists, who believed that the end of rebel rule entitled them to taking in the reins of their States. Having resisted the Confederacy and suffered greatly for the cause of the Union, Southern Unionists were characterized by a “hatred of those who went into the Rebellion” and the “ruling class” that had plunged the region into ruin by seceding, and then executing the coup to prevent a negotiated peace. But loyalty to the Union did not necessarily mean a complete acceptance of the new order. Many had accepted emancipation only reluctantly; few supported Black civil rights. Certainly, the coup and the Jacquerie had strengthened Unionist sentiments or turned many away from the Confederacy. But there remained many who could denounce slaveholders and in the same breath express bitter racism against Black freedmen. However, there were also many who had decided that an alliance with Yankees and former slaves, even if it required Black suffrage, was better than being placed again under the rule of the planter aristocracy.

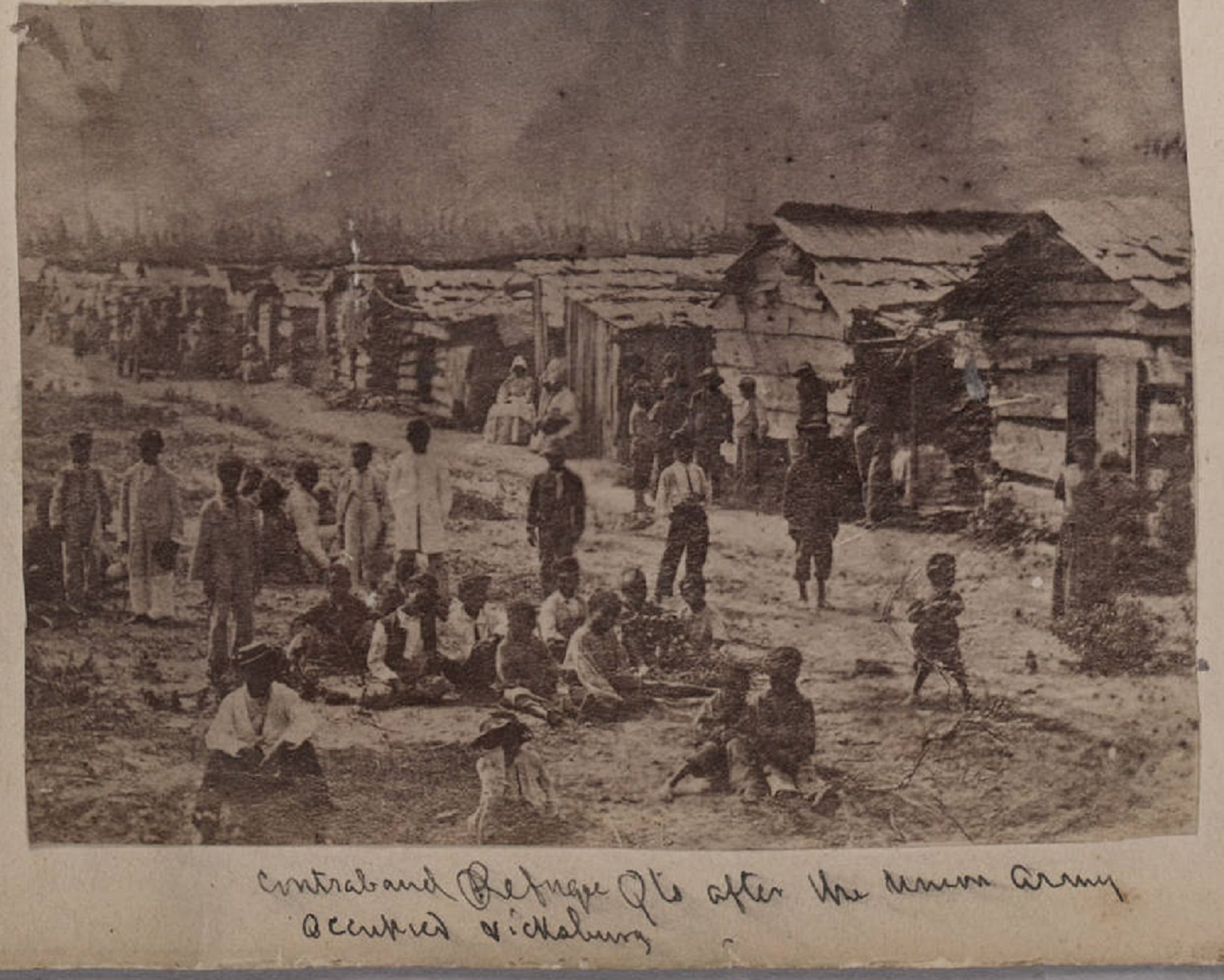

The Second Revolution also opened new avenues for Black people to assert their freedom and agency in this new South. In all sorts of gatherings and conventions throughout the region, which would have been simply impossible to even imagine before emancipation, Black people expressed their vision for a new nation where “the wall of prejudice” would be knocked down and “all of our race . . . would be able to dwell under the bright and genial rays of universal liberty.” Noting how “in the darkest hour of American history . . . we remained loyal to the Government of the United States” and “gladly came forth to fight her battles and to protect the flag that enslaved us,” Black citizens demanded equality, the right of suffrage, and political influence in their States as just their due payment for their loyalty and bravery. They further demanded the redistribution of lands as reparations for their years of unrequited toil, joined together to seize plantations and then defend themselves against terrorists, and called on the Federal government to not only declare their rights, but to defend them, to make this newfound freedom accessible and meaningful. In this way, Black people and their Radical allies continued to push for the project of a new nation.

The dream of a new nation did not merely require loyal States, but ones built on new foundations of social and economic life.

The defeat of the South did not necessarily imply its Reconstruction. With the Southern States compelled back into the Union, the government could have allowed its local elites to rule them in exchange of loyalty, betraying its Black and Unionist allies and restoring the Union as it was, or at least as closely as possible to it. But the governing Republicans could not accept this, instead adopting a program of revolutionary change fostered and defended by National power. This was made clear by Lincoln’s long awaited new announcement to the people of the South, where he appointed provisional governors to each state but maintained them under military rule, with the Army being empowered to protect the rights of loyalists. The new governments would have to elect constitutional conventions by universal male suffrage, that is, including Black voters, to create new constitutions that had to recognize the end of slavery, equality under the law, the civil rights declared by Congressional legislation, and land redistribution. The Proclamation of Reconstruction, furthermore, not only affirmed the exclusions in the Proclamation of Amnesty, but extended them to exclude most former Confederates and to punish the rebel leadership. Herein laid the promise of a radical Reconstruction.

The United States thus would build a new South on new foundations, not simply compel loyalty from the old one. The former structures of power were to be demolished and replaced; the former political and economic rulers were to be exiled, imprisoned, or even executed; and the Southern economy of large plantations and enslaved labor was to be remade into one of independent yeomen and free labor. This was, Downs writes, “a laudable but risky effort to go beyond most occupiers and attempt to remake the society it had conquered.” The government had been given the choice to “accommodate white rebels and accept the persistence of either slavery or the vestiges of slavery,” but it instead decided to enforce liberty and equality in a region that still resisted both. “From the moment the United States committed to overturning Southern society,” Downs concludes, “the die was cast for a long, violent struggle that would be decided as much by force as by law or politics.”

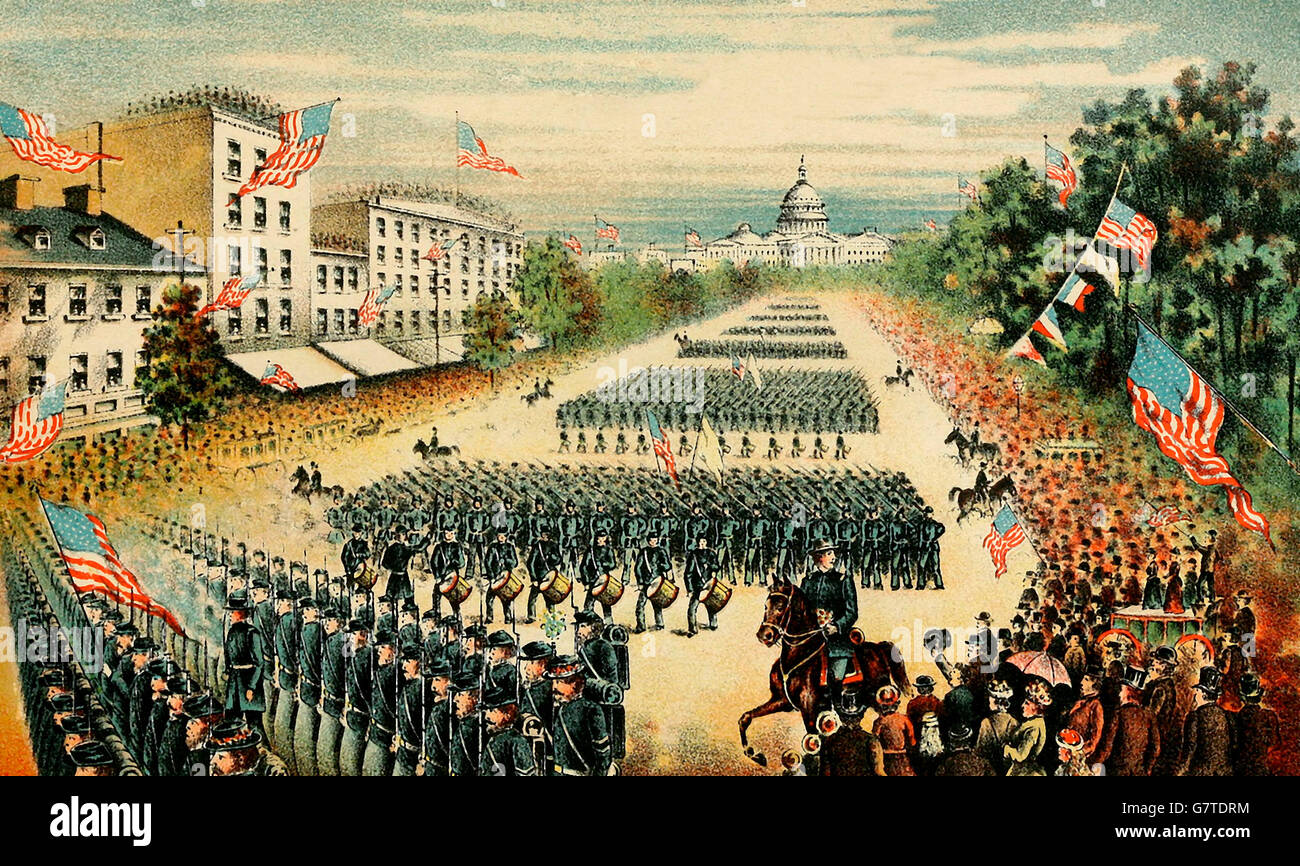

In May 1865, the three victorious Union armies, Grant’s Army of the Susquehanna, Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland, and Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee, all gathered in Washington for the Grand Review of the Union Armies. This parade marked the victory of the Union and the return of the National Government to Washington after over four years in Philadelphia. The heretofore desolated Washington now was a scenario of jubilation, as thousands of civilians poured into it to throw flowers on the path of the soldiers and wave the bright flag of the reunited American nation. The two hundred thousand soldiers, including several USCT regiments such as the 54th Massachusetts, would march amidst buildings that were still being reconstructed, including a new Capitol this time built by an entirely free force of both Black and White workers. Victory had come, and with it peace and the demobilization of the armies, and although the nation, like its capital, had not been completely reconstructed yet, there was hope that soon enough new foundations of equality and racial cooperation could be laid.

The Grand Review

But the festive mood obscured the fact that over one hundred thousand soldiers would remain in a South still under famine and rebellion, and that the fight for a true peace was only starting. Yet there was no other option, an Illinois Yankee observed. Having committed themselves to Reconstructing the Union, Americans now “must live in the world the War made” – a world of revolutionary change, deep and oftentimes bloody conflict, and battles for defining and asserting freedom, democracy, and rights. By choosing to remake the nation, the US government started a White Southern insurgency that would violently resist the tide of the Revolution, leading to a struggle for peace that was in its own way just as difficult as the struggle for victory in the Civil War. But this was also a world of hope, new opportunities, and new visions for a better nation, one truly founded on liberty and equality. That war had maintained the unity of the country, but Reconstruction, the Second American Revolution, would remake it, forever changing the United States and defining it as a nation.

Last edited: