You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Osman Reborn; The Survival of Ottoman Democracy [An Ottoman TL set in the 1900s]

- Thread starter Sarthak

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 110 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Holidays in the Ottoman Empire Chapter 66: The Swedish Republic of Ostrobothnia & Growing Disillusionment Look into the future [4] Chapter 67: cultural update – The Top 3 Sports in the Ottoman Empire turtledoves 1926 Ottoman General Elections Map. Chapter 68: African Rumblings. Chapter 69: Land of the UnfreeA lot of it will come down to what side the Ottoman Empire and Great Britain end up coming in on. Great Britain is fairly easy to predict - they have existing treaties with France and Russia, so unless some-one does something stupid they will likely get pulled in that way. The Ottoman Empire, as discussed previously, will be a lot more complicated.any predictions in regards to ittl WW1?

To talk about naval matters for a second, Germany presumably will have retained the Goeben, and if she and Breslau don't go to the Ottomans, there are lots of ways they could be used. Obviously, Goeben could have stayed with the other Battlecruisers, but the possibilty also exists that she could be used as a powerful commerce raider. The British struggled to deal with von Spee's cruisers - a rogue Battlecruiser on the loose would be serious trouble.

Well anything can happen at this stage, so we had to see how the war goes.any predictions in regards to ittl WW1?

Also reply to previous discussion about Britain: if they stay neutral, can France and Russia alone able to defeat Germany?

It might make Command decisions on the Western Front easier if France is aloneAlso reply to previous discussion about Britain: if they stay neutral, can France and Russia alone able to defeat Germany?

A-H won't have to deal with Serbia or Italy. So there is a plus for them.any predictions in regards to ittl WW1?

And they are supposedly going to be on Defensive against Russia.

But considering that their intelligence head is a Russian spy, maybe Russia will be able to circumvent some of the defences but considering that A-H won't have to fight on three fronts, I think A-H will do better here.

They might be able to hold their fronts against Russia without German assistance, which might allow Germany to do even better against Russia (?, I am not that sure about it)

I have heard that Russia was the fastest growing economy back before WWI. Though I don't know how much good a extra year would do for them. But Russia will do better than OTL simply because Bosphorous will be open for them.

French plan 17 might be bit more successful (due to Alscae Lorraine)

But some of their troops will also be tied down in the Alps.

I think Britian will join the Entente (later or early but they will join against Germany).And here is a question I had for some time. If Plan 17 was somewhat successful (not totally), would they do worse against Schlieffen plan, because they would have even more exposed flank. Like how Hannibal did Cannae, he depressed his centre (like how plan 17 will push the Germans along the Rhine) and then attacked their flanks (which the Schlieffen plan would do)?

Italy will do same as OTL(?)

Deleted member 117308

I think Britain will definitely join the Entente at some point, even if Germany does not execute the Schliefen Plan. The Ottomans clearly do not like the Italians, but they also have a negative opinion on the Russians and the French (the French supported Italy during the invasion of Lybia).

The Ottomans have no reason to support Russia. I think the Ottomans will remain neutral until Russia falls and then will join the Entente, to weaken Italy and maybe regain Bosnia.

The Ottomans have no reason to support Russia. I think the Ottomans will remain neutral until Russia falls and then will join the Entente, to weaken Italy and maybe regain Bosnia.

Ottomans are supposed to be involved in their own little war in the Balkans (If I understood what OP was trying to say).The Ottomans have no reason to support Russia. I think the Ottomans will remain neutral until Russia falls and then will join the Entente, to weaken Italy and maybe regain Bosnia.

So I don't think they will do much in the intial years of the great war.

Afterwards they will join the side, they think would win.

Hey Sarthaka, out of curiosity what would the Jewish population of the Ottoman Empire be TTL around late 1914-early 1915. The 1905-1906 census gave a population of around 260,000, and with increased Jewish immigration in the years since as well as natural population growth would a population of around 350,000 be accurate?

Romania wins.any predictions in regards to ittl WW1?

Balkan wars, ottomans either ask romania to join them for Bulgarian land, or ottomans force Bulgaria to lose it anyway to weaken them, or lastly romania starts a war after taking it.

Got a question if there is a post ww2 era esq and then progressive era, how will ottomans stop ottoman jews from then just moving to palestine?

Lastly do jews form their own military units or mixed?

Lastly do jews form their own military units or mixed?

My knowledge in modern Ottoman military is not very in depth but I have never heard anything about ethnic or religious segregation in Ottoman military.

Chapter 19: War Arrives

Chapter 19: War Arrives

***

“When war was declared between Germany and France, and subsequently, Europe fell into war, France was on the backfoot. They had the need to garrison their border in the Alps with Italy and had to form a plan to invade Italian Eritrea and Italian Somalia, both of which seemed like a daunting proposal, considering there was a limit to how many troops France could commit to Djibouti. Nonetheless, the French were quite optimistic about the war, and many in the government, and the people cajoled each other stating that this was a war that at maximum, would be over by Christmas.

German Chief of Staff, Karl von Bulow

Karl von Bulow, the German Chief of Staff, was planning on pulling through with the old Schlieffen Plan. German strategy had given priority to offensive operations against France and had a defensive posture against Russia since 1891. Germany planning was determined by numerical inferiority, the speed of mobilization and the concentration and the effect of the vast increase of the power of modern weapons. Frontier attacks were expected to be brutal and very costly as well as protracted, with expected results to be limited, especially after France and Russia modernized their border fortifications on the frontiers of Germany. Karl von Bulow followed through with Alfred von Schlieffen’s plan of bypassing French defenses by conducting a maneuver through Namur and Antwerp in Belgium to threaten Paris itself from the north. Helmuth von Moltke took power in 1906 to become the Chief of General Staff and was less certain about the plan, and modified it to have more troops, increasing the number from 1.3 million to 1.7 million into the Westheer or the Western Army. Moltke instead wished to have the support of the Austro-Hungarian Army in the eastern front to make up for the disturbing lack of German troops on the eastern front itself.

However this plan meant that Belgium would need to be subdued, browbeaten into submission to Germany, either through diplomacy or force if needed. And Germany was willing to use force if needed. On February 19, the British government announced the mobilization of the Royal Navy after the first declaration of war was announced. Hostilities of small skirmishes broke out all over Alsace-Lorraine and the Polish border. On February 23, the German government sent an ultimatum to the Belgian government in Brussels, demanding passage through Belgian territory, as German troops crossed the frontier with Luxembourg to outflank French positions near Alsace-Lorraine.

Meanwhile in Belgium, the government since May 1914 under Chief of General Staff Antonin de Selliers de Moranville and King Albert I had been planning for a concentration of the army in the east on the german border, and met with railway officials in June to coordinate strategy. As the Alsatian Crisis spilled over into the rest of the Europe, Belgium declared armed neutrality and Albert I ordered the mobilization of troops on February 21. Belgian troops were to be amassed in central Belgium, in front of the national redoubt at Antwerp, ready to face any border, whilst the fortified position of liege, and the fortified position of Namur were left to secure the frontiers, a suicide mission in all regards.

Britain watched the developments worriedly and sent delegations to both Paris and Berlin on February 19, asking whether or not the French and German governments would respect Belgian neutrality. The French government assured the British that the French military would respect Belgium’s neutrality, however worryingly so, the Germans gave no answer.

When Germany issued the ultimatum on February 23, they gave until the end of February 24 to form a response for the Belgians. The Belgians were taken off guard by the ultimatum, whilst they had known it was a great probability, they weren’t actually sure that the Germans would do it, as violating neutrality in this day and age was quite unexpected and thought long past in European military politics and actions. On February 24, the Belgian government replied by rejecting the German ultimatum for passage and the Belgian government asked for support from the British government if Germany invaded. On February 25, German troops crossed the Belgian frontier and attacked the defenses at Liege.

In Britain itself, the Liberal Party, governing the government, and led by Prime Minister Asquith and its voters were anti-war, whilst the Tories remained pro-war. As Germany and France became the central players in the crisis, British leaders had an increasing commitment to the defense of France. First if Germany again conquered France, as had happened in 1870, it would become a major threat to British economic, political and cultural interests. Second and perhaps more importantly, partisanship was involved. The Liberal Party identified with internationalism and free trade, as opposed to warfare and jingoism. By contrast, the Conservative Party was defined as the party of Nationalism and Patriotism. Britons expected that the Tories would show the capacity of running in a war as such. Liberal voters initially wanted peace, and demanded as such, however found themselves outraged when Germany invaded Belgium and breached the Treaty of London of 1839, which was being derided by the German press as a worthless scrap of paper.

Liberal politician and future prime minister, David Lloyd George would tell reporters “Up until day before tomorrow, only a few members of the cabinet were in favor of intervention in the new war, however the violation of Belgian territory and sovereignty as well as neutrality has completely altered the situation.”

On the evening of February 25, the British government sent an ultimatum to Germany and demanded that the Germans withdraw from Belgium or face war. The ultimatum would expire the next day without the Germans replying to the ultimatum, and parliament voted in favor of declaring war on the Germans. On February 26, the British government finally formally declared war on the German Empire, though deliberation was being committed for a declaration of war against Italy and Austria-Hungary, as some wished to leverage Italy’s economic dependence on British imports to their advantage.

German troops entering Belgium

However soon enough, the declarations of war soon took place between Austria-Hungary and Italy with the United Kingdom as well, making war the only option left.” Great Britain in the Great War. University of Nantes, 1988.

“The first major action between France and Germany during the opening stages of the war was the Battle of Mulhouse/Mulhausen which took place in German Alsace from between February 28 to 9 March, 1915. It would culminate to become one of the dark forerunners of the upcoming battle of wits and blood during the Great War.

In Alsace, as war tensions ramped up during the Alsatian crisis, the deployment plan of the 7th Army was given to the command of General Josias von Heeringen, with the XIV, XV, XIV Reserve Corps alongside the 60th Landswehr Brigade forming the aegis of the German troops in Alsace. The 1st and 2nd Bavarian Brigades, alongside the 55th Landswehr Brigade, the 110th Landswehr Regiment, and a battery of heavy field howitzers were also added to the army under the provisional command of the XIV corps as mobilization continued. Meanwhile the French had mobilized the VII, VIII, XIII, XXI, XIV Corps and the 6th Cavalry Division to form the 1st Army or the Army of Alsace. The 14th, and 41st Divisions, alongside the 57th Reserve Division and the 8th Cavalry Division formed the southern flank of the 1st Army becoming a miniature army of its own.

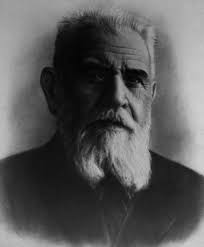

General Dubail

A few border skirmishes took place between the German and French patrols as soon as war was declared. These skirmishes weren’t decisive, however they were enough to give Germany the information that the French had a chain of border frontier posts, supported by a larger position behind which was heavily fortified. The French stayed true to their idea of an offensive doctrine and advanced through German positions on the frontiers and advanced to the Schluct Pass, where the Germans were forced to blow up the tunnel to delay the French. Joffre received information from General August Dubail, the commander of the 1st Army about the holdup of French forces, and directed the VII Corps led by General Louis Bonneau with the 14th Division to advance on the flanks and rears to lessen the pressure on the central force of the 1st Army. The French were successful. The French advanced from Belfort all the way to Mulhouse and Colmar 35 kilometers to the north east and were only really hampered by the breakdown of supply service and delays in equipment supply. The local Alsatian population egged the French on, and aided the French in many ways that they could, feeding some of the troops, and giving the thirsty troops some water to drink when they wanted, and a few volunteer regiments signed up in the French army as well. The French were becoming more confident, as it was obvious whom the local population seemed to prefer.

a painting of the Battle of Mulhouse

The French seized the border town of Altkirch 15 kilometers south of Mulhouse with a small bayonet charge and forced the small German garrison there to retreat again. On March 4, Bonneau continued to advance and occupied Mulhouse, after a small engagement with the 58th Infantry Brigade of the Germans was forced to retreat. The 1st Army Commander, Dubail, preferred to dig in and wait for mobilization to finish but Joffre ordered the advance to continue. Dubail went against orders and instead dug the vast majority of his troops into defensive entrenchments and sent only a small portion of his force to continue the advance. On March 6th, the parts of the XIV and XV Corps of the German 7th Army arrived from Strasbourg and counter-attacked at Cernay. The Germans and their infantry emerged from the Hardt forest, and advanced into the east side of the city. Communications on both sides collapsed temporarily, and both sides of troops fought independently in isolated actions, with the Germans especially making costly frontal attacks. As night fell, the Germans continued to advance in the suburb of Rixheim, east of Mulhouse, and inexperienced German troops fired wildly on both sides, wasting huge amounts of ammunition and occasionally shooting each other as well.

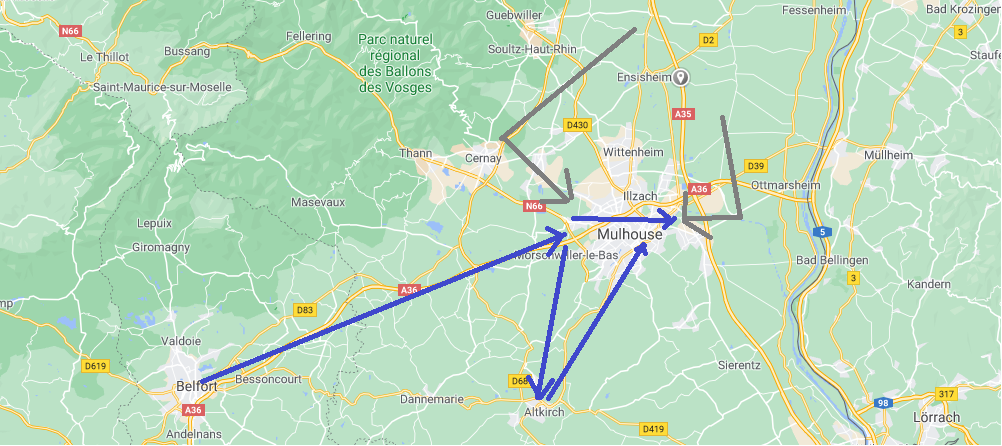

Strategic map of the Battle of Mulhouse. Blue lines depict French movements and Grey lines depict German movements.

The Germans then tried to assault the main defensive line made by Dubail, however Dubail’s defensive line managed to stall the Germans enough for 57th Reserve Division to arrive and create a flanking action, defeating the Germans pushing them out of the Mulhouse area entirely being pushed out entirely. The battle of Mulhouse saw the loss of around 2500 French lives and around 3000 German lives, making it the first major battle of the war. The battle was extremely consequential as well, as it assured southern Alsace, and most of the Alsatian regions barring Strasbourg and its surroundings fell to French occupation for the duration of the war in its entirety.” The Battle for Alsace: 1915. Max Hastings, Penguin Publishing, 1992.

“Tensions among the Balkan states over their overlapping religious and ethnic claims in the Ottoman controlled Rumelia, Thrace and Maacedonia subsided after the intervention of the Great Powers in 1878 and 1881, which aimed to secure a more complete protection for the province’s Christian majority population as well as a way to maintain the status quo. By 1867, Montenegro and Serbia had gained their independence which was confirmed by the Treaty of Berlin 1878, and Romania had long been taken out of the Ottoman Sphere of Influence. For decades, the Balkan question remained calm and one of tepid calm, until the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, which revived questions of viability of future Ottoman rule in the Balkans once again. Serbia’s aspirations to take over Bosnia and Herzegovina were thwarted by the Bosnian Crisis of 1908 which led to the Austrian annexation of the province in 1908 triggering a Europe wide diplomatic crisis that almost led to war. The Serbs wary of Austrian military might turned their attention of war to the south.

Prime Minister Stanojevic of Serbia

The Serbians and Bulgarians stood down for their belligerent stance when the Ottomans kicked the Italians out of Libya, reaffirming their ailing, but still worthwhile status as a great power within global geopolitics. However the interference of the British and German governments in favor of the Ottomans had given an impression that the British and Germans were the guarantors of Ottoman territorial sovereignty. With Europe descending into war, with the British and Germans directly involved in the Great War with one another, the diplomats in Belgrade, and Sofia started to believe that this was their most opportune time to take control of the territories that they regarded as rightfully theirs. Montenegro led by King Nicholas I was all for the idea, and even pledged the support of his country’s 25,000 troops immediately. Secret negotiations began to take place with the Greeks as well as Stanojevic, a Yugoslavic nationalist who was becoming increasingly pressured by the rest of his armed parliament to take action against the Ottoman government.

There was a flaw into the Greco-Serbian negotiations. The Serbians assumed that the Greeks would jump for a chance against the Ottomans without question, however were rudely beaten back diplomatically when the Greek diplomats pointed out that the Ottomans and their economic deal with Greece was greatly benefitting both countries involved. Whilst the Serbs and Bulgarians could take up the economic trade deficit to replace the Ottomans in the case of war, neither the Serbs or Bulgarians combined had enough economic clout as that of the Ottomans, and the Greek stock marketers were up in arms against any idea of a war against the Ottoman Empire, especially as some of the effects of the American Great Depression seeped into the Greek Kingdom. King George I of Greece, who was planning for his abdication as he grew older and older as days passed, also found himself frowning at the economic implications of the notion.

King George I of Greece

There was of course the idea of losing preferential trading status which would make Greece lose the savvy markets of Hejaz, the Levant and the Persian Gulf, and the heavy amount of imports and exports between Greece and the Ottoman Empire over the past few years had made economic dependence with each other more and more lucrative and made the idea of war all the more limiting in the eyes of many Greeks in the Kingdom of Greece. The second reason was also because of the burgeoning Ottoman democracy, which had led to a dampening of nationalistic feelings within the Ottoman Empire, and Ottoman Greeks. The election of a moderate Ottoman Greek to the Princedom of Samos, and the failure of Greek nationalistic parties to gain electoral threshold were testament to this fact. As long as the Ottomans remained democratic and respected the opinions of its minorities, especially the greeks, the Greek government doubted that the population would really be welcoming of Greek invasion, much less the non-Greek population of the areas that Greek nationalists aimed for. The third reason was the growing reforms of the Ottoman Army and Ottoman Navy which hadn’t gone noticed by the Greeks. Greek military attaches in Constantinople brought back news of massive reforms, and massive fortifications, and of course the 1911 Naval Plan had managed to bring the Ottomans back to a position of formidable naval power, which worried Greece, as they were predominantly a maritime trade power. As the Serbians and Bulgarians were unable to provide a proper replacement for the loss of Ottoman markets, as well as the fact that the Greek Navy would not be able to stop Ottoman reinforcements in the Balkans with the recent naval developments, Venizelos stalled the secret negotiations with Belgrade and Sofia.

Meanwhile, Ahmet Riza was wizening up to the threat being made to the Ottoman Empire as Ottoman Military Attaches reported suspicious movements of the Bulgarian and Serbian militaries. He had the Ottoman Intelligence work for breaking the telegraph codes and lines once again. Ottoman codebreakers managed to break the communication codes between Serbia and Greece just before Venizelos started to drag his feet over negotiations and the Ottomans quickly found out what was happening. The Ottomans ordered a secret partial mobilization of reserves in the Balkans whilst Ahmet Riza assigned a group of 12 diplomats to start secret negotiations with Athens to secure Greek neutrality in a future Balkan War, which Riza thought to be inevitable by that point.

On March 18, the Ottoman delegation arrived in Athens and began hushed negotiations with the Greeks. Venizelos of course wizened up to the fact that the Ottomans had probably found out that diplomatic intrigue had taken place between Athens and Belgrade, and was willing to hear the Ottomans out. The Ottomans directed by Riza offered the Greeks more economic access in the Ottoman Empire, and its approaches and links with the Asian economy. The Ottomans also more importantly offered border corrections with the Greco-Ottoman border, and offered the Greeks the Preveza Sanjak, all of the Northern Aegean Islands other than Lemnos and the areas ceded by Greece in 1897 back if the Greeks remained neutral in a near inevitable future war. This was of course a very convincing offer, as the Greeks would be able to enrich themselves more, and gain considerable land in the process. However Venizelos tried to push for more, and asked for the Tymfala Corridor, which the Ottomans wanted to keep as well, and Greek supervised plebiscites in Lemnos and Lesbos. The Ottomans accepted the first demand and agreed to give the Tymfala Corridor to the Greeks, however rejected any idea of giving Lemnos and Lesbos to Greece. Instead Riza compromised that the Greeks would be allowed to send Consuls to the islands and legations to check on the situation indefinitely and allow the Greek population of the island have their democratic rights within the empire affirmed. Venizelos also raised the idea of a naval treaty, and maintaining the current status quo of gross tons of the Royal Hellenic Navy and the Ottoman Imperial Navy, to which Riza hesitantly agreed.

The (Secret) Treaty of Athens was signed between the Ottomans and Greeks on March 29, 1915 and stipulated the following points:-

The border agreement with Greece after the Secret Treaty of Athens.

On March 31st the opposition parties within the Ottoman government tried to lambast the transfer of territories and denounce it, however the same time the Ottoman government received a declaration of war from Bulgaria and Serbia and Montenegro citing liberation of their ethnic peoples.” Diplomacy within the Balkan War. University of Odessa, 2019.

“When the Balkan War had been declared, the Russians were just as caught off guard as the Ottomans. The Russians were busy fighting a massive war against Austria-Hungary and Germany, and they certainly didn’t want to drag the Ottomans into that extensive list. They made diplomatic noises in favor of the Balkan Alliance, however only gave lip service to the support they would give to the governments in Belgrade and Sofia. The Russians preferred to keep their flanks secured.

The Ottomans when war broke out had around 350,000 men mobilized in the Balkans with some 400,000 en route to the Balkans from the Anatolian armies as the Ottoman mobilization continued in earnest and now expanded without the need to conduct it in secret. Ahmet Riza formed a national government, entering into a temporary coalition with every political party present in the Ottoman Chamber of Deputies and the Ottoman Senate and declared war time law.

The Ottoman flag used during the Balkan War. This flag depicts the Exalted Ottoman State during times of war.

The first engagement of the Balkan War took place in the strategic fortress town of Kardzhali. Shortly before the war, Bulgaria had deployed the 2nd Thracian Infantry Division reinforced with 3 artillery regiments to the area around Haskovo and had orders to protect the routes between Plovdiv and Stara Zagora. The Ottoman forces in Kardzhali were dangerously close to the Plovdiv-Harmanli railway line and the base of the Bulgarian Armies which were to advance in Eastern Thrace. The commander of the 2nd Army, Nikola Ivanov ordered the 2nd Army to advance towards the fortress city, the first city in a long range of fortifications across the Rhodope Mountains and to push the Ottomans to the south of the Arda River.

Meanwhile, the local commander of the area, Mehmed Yaver Pasha received orders from Mustafa Kemal, the commander of the Rhodope and Bulgarian Front, who had hastily come back into service splitting his honeymoon time in half, and was ordered to defend the first fortress city to allow reinforcements to arrive. Yaver Pasha had around 15,000 troops in the region, consisting largely of the 3rd Mountaineer Division. Meanwhile on the other hand, Ivanov had around 20,000 men consisting of the 2nd Thracian Division and the 40th Infantry Division converging on Kardzhali.

On April 2nd, 1915, the artillery regiments of the Bulgarians opened fire on the Ottoman fortifications which returned fire, beginning a massive cannonade between the two forces. Colonel Vasil Delov was ordered to take independent command of four columns and Delov took command as ordered. His four columns marched into the village of Kovancilar after defeating the small Ottoman garrison there, and started to heard for Kardzhali in a small flanking maneuver. Yaver Pasha hearing of this sent 3,000 troops under the command of Neshat Bey, the famous commander from the Italo-Ottoman War to counter attack against Delov and his troops and relieve the Ottoman flanks in the region.

After Neshat Bey drove the Bulgarians out of the villages surrounding Kardzhali, General Ivan Fichev, in total command of the Bulgarian Rhodope Front ordered General Ivanov to stop the advance of the 2nd Army against Kardzhali because the Bulgarians weren’t aware of the total Ottoman strength in the region. However, Ivanov did not withdraw his troops as ordered by the Bulgarian high command, and gave his officers autonomy and freedom of command and action. The detachment led by Delov counter attacked against Neshat Bey again and managed to retake some of the outlying villages. Neshat Bey managed to hold his ground and defend the flanks of the fortress however.

With that out of the way on April 4, Yaver Pasha received 1000 reinforcements and decided to take a risk and 10,000 Ottoman troops sallied out of the fortress lines and accompanied with artillery and cover fire, and attacked the Bulgarian positions. The Bulgarians were taken aback by the sudden attack, especially amidst torrential rain and the surprise factor, as well as the superior artillery that the Ottomans possessed with them pushed the Bulgarians out of Kardzhal for good.

a depiction of the Battle of Kardzhali

As the Ottomans won the first land engagement of the war, the Ottoman Black Sea Fleet also declared a blockade of the Tsardom of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Adriatic Fleet also declared a blockade of Montenegro, thus starting the war in absolute earnest.” The War in the Balkans: Ottoman Validation. Penguin Publishing, 2007.

***

***

“When war was declared between Germany and France, and subsequently, Europe fell into war, France was on the backfoot. They had the need to garrison their border in the Alps with Italy and had to form a plan to invade Italian Eritrea and Italian Somalia, both of which seemed like a daunting proposal, considering there was a limit to how many troops France could commit to Djibouti. Nonetheless, the French were quite optimistic about the war, and many in the government, and the people cajoled each other stating that this was a war that at maximum, would be over by Christmas.

German Chief of Staff, Karl von Bulow

Karl von Bulow, the German Chief of Staff, was planning on pulling through with the old Schlieffen Plan. German strategy had given priority to offensive operations against France and had a defensive posture against Russia since 1891. Germany planning was determined by numerical inferiority, the speed of mobilization and the concentration and the effect of the vast increase of the power of modern weapons. Frontier attacks were expected to be brutal and very costly as well as protracted, with expected results to be limited, especially after France and Russia modernized their border fortifications on the frontiers of Germany. Karl von Bulow followed through with Alfred von Schlieffen’s plan of bypassing French defenses by conducting a maneuver through Namur and Antwerp in Belgium to threaten Paris itself from the north. Helmuth von Moltke took power in 1906 to become the Chief of General Staff and was less certain about the plan, and modified it to have more troops, increasing the number from 1.3 million to 1.7 million into the Westheer or the Western Army. Moltke instead wished to have the support of the Austro-Hungarian Army in the eastern front to make up for the disturbing lack of German troops on the eastern front itself.

However this plan meant that Belgium would need to be subdued, browbeaten into submission to Germany, either through diplomacy or force if needed. And Germany was willing to use force if needed. On February 19, the British government announced the mobilization of the Royal Navy after the first declaration of war was announced. Hostilities of small skirmishes broke out all over Alsace-Lorraine and the Polish border. On February 23, the German government sent an ultimatum to the Belgian government in Brussels, demanding passage through Belgian territory, as German troops crossed the frontier with Luxembourg to outflank French positions near Alsace-Lorraine.

Meanwhile in Belgium, the government since May 1914 under Chief of General Staff Antonin de Selliers de Moranville and King Albert I had been planning for a concentration of the army in the east on the german border, and met with railway officials in June to coordinate strategy. As the Alsatian Crisis spilled over into the rest of the Europe, Belgium declared armed neutrality and Albert I ordered the mobilization of troops on February 21. Belgian troops were to be amassed in central Belgium, in front of the national redoubt at Antwerp, ready to face any border, whilst the fortified position of liege, and the fortified position of Namur were left to secure the frontiers, a suicide mission in all regards.

Britain watched the developments worriedly and sent delegations to both Paris and Berlin on February 19, asking whether or not the French and German governments would respect Belgian neutrality. The French government assured the British that the French military would respect Belgium’s neutrality, however worryingly so, the Germans gave no answer.

When Germany issued the ultimatum on February 23, they gave until the end of February 24 to form a response for the Belgians. The Belgians were taken off guard by the ultimatum, whilst they had known it was a great probability, they weren’t actually sure that the Germans would do it, as violating neutrality in this day and age was quite unexpected and thought long past in European military politics and actions. On February 24, the Belgian government replied by rejecting the German ultimatum for passage and the Belgian government asked for support from the British government if Germany invaded. On February 25, German troops crossed the Belgian frontier and attacked the defenses at Liege.

In Britain itself, the Liberal Party, governing the government, and led by Prime Minister Asquith and its voters were anti-war, whilst the Tories remained pro-war. As Germany and France became the central players in the crisis, British leaders had an increasing commitment to the defense of France. First if Germany again conquered France, as had happened in 1870, it would become a major threat to British economic, political and cultural interests. Second and perhaps more importantly, partisanship was involved. The Liberal Party identified with internationalism and free trade, as opposed to warfare and jingoism. By contrast, the Conservative Party was defined as the party of Nationalism and Patriotism. Britons expected that the Tories would show the capacity of running in a war as such. Liberal voters initially wanted peace, and demanded as such, however found themselves outraged when Germany invaded Belgium and breached the Treaty of London of 1839, which was being derided by the German press as a worthless scrap of paper.

Liberal politician and future prime minister, David Lloyd George would tell reporters “Up until day before tomorrow, only a few members of the cabinet were in favor of intervention in the new war, however the violation of Belgian territory and sovereignty as well as neutrality has completely altered the situation.”

On the evening of February 25, the British government sent an ultimatum to Germany and demanded that the Germans withdraw from Belgium or face war. The ultimatum would expire the next day without the Germans replying to the ultimatum, and parliament voted in favor of declaring war on the Germans. On February 26, the British government finally formally declared war on the German Empire, though deliberation was being committed for a declaration of war against Italy and Austria-Hungary, as some wished to leverage Italy’s economic dependence on British imports to their advantage.

German troops entering Belgium

However soon enough, the declarations of war soon took place between Austria-Hungary and Italy with the United Kingdom as well, making war the only option left.” Great Britain in the Great War. University of Nantes, 1988.

“The first major action between France and Germany during the opening stages of the war was the Battle of Mulhouse/Mulhausen which took place in German Alsace from between February 28 to 9 March, 1915. It would culminate to become one of the dark forerunners of the upcoming battle of wits and blood during the Great War.

In Alsace, as war tensions ramped up during the Alsatian crisis, the deployment plan of the 7th Army was given to the command of General Josias von Heeringen, with the XIV, XV, XIV Reserve Corps alongside the 60th Landswehr Brigade forming the aegis of the German troops in Alsace. The 1st and 2nd Bavarian Brigades, alongside the 55th Landswehr Brigade, the 110th Landswehr Regiment, and a battery of heavy field howitzers were also added to the army under the provisional command of the XIV corps as mobilization continued. Meanwhile the French had mobilized the VII, VIII, XIII, XXI, XIV Corps and the 6th Cavalry Division to form the 1st Army or the Army of Alsace. The 14th, and 41st Divisions, alongside the 57th Reserve Division and the 8th Cavalry Division formed the southern flank of the 1st Army becoming a miniature army of its own.

General Dubail

A few border skirmishes took place between the German and French patrols as soon as war was declared. These skirmishes weren’t decisive, however they were enough to give Germany the information that the French had a chain of border frontier posts, supported by a larger position behind which was heavily fortified. The French stayed true to their idea of an offensive doctrine and advanced through German positions on the frontiers and advanced to the Schluct Pass, where the Germans were forced to blow up the tunnel to delay the French. Joffre received information from General August Dubail, the commander of the 1st Army about the holdup of French forces, and directed the VII Corps led by General Louis Bonneau with the 14th Division to advance on the flanks and rears to lessen the pressure on the central force of the 1st Army. The French were successful. The French advanced from Belfort all the way to Mulhouse and Colmar 35 kilometers to the north east and were only really hampered by the breakdown of supply service and delays in equipment supply. The local Alsatian population egged the French on, and aided the French in many ways that they could, feeding some of the troops, and giving the thirsty troops some water to drink when they wanted, and a few volunteer regiments signed up in the French army as well. The French were becoming more confident, as it was obvious whom the local population seemed to prefer.

a painting of the Battle of Mulhouse

The French seized the border town of Altkirch 15 kilometers south of Mulhouse with a small bayonet charge and forced the small German garrison there to retreat again. On March 4, Bonneau continued to advance and occupied Mulhouse, after a small engagement with the 58th Infantry Brigade of the Germans was forced to retreat. The 1st Army Commander, Dubail, preferred to dig in and wait for mobilization to finish but Joffre ordered the advance to continue. Dubail went against orders and instead dug the vast majority of his troops into defensive entrenchments and sent only a small portion of his force to continue the advance. On March 6th, the parts of the XIV and XV Corps of the German 7th Army arrived from Strasbourg and counter-attacked at Cernay. The Germans and their infantry emerged from the Hardt forest, and advanced into the east side of the city. Communications on both sides collapsed temporarily, and both sides of troops fought independently in isolated actions, with the Germans especially making costly frontal attacks. As night fell, the Germans continued to advance in the suburb of Rixheim, east of Mulhouse, and inexperienced German troops fired wildly on both sides, wasting huge amounts of ammunition and occasionally shooting each other as well.

Strategic map of the Battle of Mulhouse. Blue lines depict French movements and Grey lines depict German movements.

The Germans then tried to assault the main defensive line made by Dubail, however Dubail’s defensive line managed to stall the Germans enough for 57th Reserve Division to arrive and create a flanking action, defeating the Germans pushing them out of the Mulhouse area entirely being pushed out entirely. The battle of Mulhouse saw the loss of around 2500 French lives and around 3000 German lives, making it the first major battle of the war. The battle was extremely consequential as well, as it assured southern Alsace, and most of the Alsatian regions barring Strasbourg and its surroundings fell to French occupation for the duration of the war in its entirety.” The Battle for Alsace: 1915. Max Hastings, Penguin Publishing, 1992.

“Tensions among the Balkan states over their overlapping religious and ethnic claims in the Ottoman controlled Rumelia, Thrace and Maacedonia subsided after the intervention of the Great Powers in 1878 and 1881, which aimed to secure a more complete protection for the province’s Christian majority population as well as a way to maintain the status quo. By 1867, Montenegro and Serbia had gained their independence which was confirmed by the Treaty of Berlin 1878, and Romania had long been taken out of the Ottoman Sphere of Influence. For decades, the Balkan question remained calm and one of tepid calm, until the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, which revived questions of viability of future Ottoman rule in the Balkans once again. Serbia’s aspirations to take over Bosnia and Herzegovina were thwarted by the Bosnian Crisis of 1908 which led to the Austrian annexation of the province in 1908 triggering a Europe wide diplomatic crisis that almost led to war. The Serbs wary of Austrian military might turned their attention of war to the south.

Prime Minister Stanojevic of Serbia

The Serbians and Bulgarians stood down for their belligerent stance when the Ottomans kicked the Italians out of Libya, reaffirming their ailing, but still worthwhile status as a great power within global geopolitics. However the interference of the British and German governments in favor of the Ottomans had given an impression that the British and Germans were the guarantors of Ottoman territorial sovereignty. With Europe descending into war, with the British and Germans directly involved in the Great War with one another, the diplomats in Belgrade, and Sofia started to believe that this was their most opportune time to take control of the territories that they regarded as rightfully theirs. Montenegro led by King Nicholas I was all for the idea, and even pledged the support of his country’s 25,000 troops immediately. Secret negotiations began to take place with the Greeks as well as Stanojevic, a Yugoslavic nationalist who was becoming increasingly pressured by the rest of his armed parliament to take action against the Ottoman government.

There was a flaw into the Greco-Serbian negotiations. The Serbians assumed that the Greeks would jump for a chance against the Ottomans without question, however were rudely beaten back diplomatically when the Greek diplomats pointed out that the Ottomans and their economic deal with Greece was greatly benefitting both countries involved. Whilst the Serbs and Bulgarians could take up the economic trade deficit to replace the Ottomans in the case of war, neither the Serbs or Bulgarians combined had enough economic clout as that of the Ottomans, and the Greek stock marketers were up in arms against any idea of a war against the Ottoman Empire, especially as some of the effects of the American Great Depression seeped into the Greek Kingdom. King George I of Greece, who was planning for his abdication as he grew older and older as days passed, also found himself frowning at the economic implications of the notion.

King George I of Greece

There was of course the idea of losing preferential trading status which would make Greece lose the savvy markets of Hejaz, the Levant and the Persian Gulf, and the heavy amount of imports and exports between Greece and the Ottoman Empire over the past few years had made economic dependence with each other more and more lucrative and made the idea of war all the more limiting in the eyes of many Greeks in the Kingdom of Greece. The second reason was also because of the burgeoning Ottoman democracy, which had led to a dampening of nationalistic feelings within the Ottoman Empire, and Ottoman Greeks. The election of a moderate Ottoman Greek to the Princedom of Samos, and the failure of Greek nationalistic parties to gain electoral threshold were testament to this fact. As long as the Ottomans remained democratic and respected the opinions of its minorities, especially the greeks, the Greek government doubted that the population would really be welcoming of Greek invasion, much less the non-Greek population of the areas that Greek nationalists aimed for. The third reason was the growing reforms of the Ottoman Army and Ottoman Navy which hadn’t gone noticed by the Greeks. Greek military attaches in Constantinople brought back news of massive reforms, and massive fortifications, and of course the 1911 Naval Plan had managed to bring the Ottomans back to a position of formidable naval power, which worried Greece, as they were predominantly a maritime trade power. As the Serbians and Bulgarians were unable to provide a proper replacement for the loss of Ottoman markets, as well as the fact that the Greek Navy would not be able to stop Ottoman reinforcements in the Balkans with the recent naval developments, Venizelos stalled the secret negotiations with Belgrade and Sofia.

Meanwhile, Ahmet Riza was wizening up to the threat being made to the Ottoman Empire as Ottoman Military Attaches reported suspicious movements of the Bulgarian and Serbian militaries. He had the Ottoman Intelligence work for breaking the telegraph codes and lines once again. Ottoman codebreakers managed to break the communication codes between Serbia and Greece just before Venizelos started to drag his feet over negotiations and the Ottomans quickly found out what was happening. The Ottomans ordered a secret partial mobilization of reserves in the Balkans whilst Ahmet Riza assigned a group of 12 diplomats to start secret negotiations with Athens to secure Greek neutrality in a future Balkan War, which Riza thought to be inevitable by that point.

On March 18, the Ottoman delegation arrived in Athens and began hushed negotiations with the Greeks. Venizelos of course wizened up to the fact that the Ottomans had probably found out that diplomatic intrigue had taken place between Athens and Belgrade, and was willing to hear the Ottomans out. The Ottomans directed by Riza offered the Greeks more economic access in the Ottoman Empire, and its approaches and links with the Asian economy. The Ottomans also more importantly offered border corrections with the Greco-Ottoman border, and offered the Greeks the Preveza Sanjak, all of the Northern Aegean Islands other than Lemnos and the areas ceded by Greece in 1897 back if the Greeks remained neutral in a near inevitable future war. This was of course a very convincing offer, as the Greeks would be able to enrich themselves more, and gain considerable land in the process. However Venizelos tried to push for more, and asked for the Tymfala Corridor, which the Ottomans wanted to keep as well, and Greek supervised plebiscites in Lemnos and Lesbos. The Ottomans accepted the first demand and agreed to give the Tymfala Corridor to the Greeks, however rejected any idea of giving Lemnos and Lesbos to Greece. Instead Riza compromised that the Greeks would be allowed to send Consuls to the islands and legations to check on the situation indefinitely and allow the Greek population of the island have their democratic rights within the empire affirmed. Venizelos also raised the idea of a naval treaty, and maintaining the current status quo of gross tons of the Royal Hellenic Navy and the Ottoman Imperial Navy, to which Riza hesitantly agreed.

The (Secret) Treaty of Athens was signed between the Ottomans and Greeks on March 29, 1915 and stipulated the following points:-

- The Greek Government and Kingdom would receive lower tariffs than other countries within the Ottoman Empire (2% instead of 5%) and become a ‘favored economic nation’ of the empire.

- The transfer of Preveza, Tymfala, the Northern Aegean Islands and the Areas ceded to the empire in 1897 to be ceded to Greece.

- The muslim population of the areas above would be allowed full access back to the Ottoman Empire.

- The Greeks and Ottomans to maintain their gross tons within their respective navies maintaining naval parity with one another.

- The greek government to send 5 consuls and 5 legations to the Ottoman Aegean to affirm the democratic rights of the Ottoman Greek population of the islands.

- The Greek government to remain neutral in any future conflict between the powers of the Ottoman Empire and the other local Balkan powers.

The border agreement with Greece after the Secret Treaty of Athens.

On March 31st the opposition parties within the Ottoman government tried to lambast the transfer of territories and denounce it, however the same time the Ottoman government received a declaration of war from Bulgaria and Serbia and Montenegro citing liberation of their ethnic peoples.” Diplomacy within the Balkan War. University of Odessa, 2019.

“When the Balkan War had been declared, the Russians were just as caught off guard as the Ottomans. The Russians were busy fighting a massive war against Austria-Hungary and Germany, and they certainly didn’t want to drag the Ottomans into that extensive list. They made diplomatic noises in favor of the Balkan Alliance, however only gave lip service to the support they would give to the governments in Belgrade and Sofia. The Russians preferred to keep their flanks secured.

The Ottomans when war broke out had around 350,000 men mobilized in the Balkans with some 400,000 en route to the Balkans from the Anatolian armies as the Ottoman mobilization continued in earnest and now expanded without the need to conduct it in secret. Ahmet Riza formed a national government, entering into a temporary coalition with every political party present in the Ottoman Chamber of Deputies and the Ottoman Senate and declared war time law.

The Ottoman flag used during the Balkan War. This flag depicts the Exalted Ottoman State during times of war.

The first engagement of the Balkan War took place in the strategic fortress town of Kardzhali. Shortly before the war, Bulgaria had deployed the 2nd Thracian Infantry Division reinforced with 3 artillery regiments to the area around Haskovo and had orders to protect the routes between Plovdiv and Stara Zagora. The Ottoman forces in Kardzhali were dangerously close to the Plovdiv-Harmanli railway line and the base of the Bulgarian Armies which were to advance in Eastern Thrace. The commander of the 2nd Army, Nikola Ivanov ordered the 2nd Army to advance towards the fortress city, the first city in a long range of fortifications across the Rhodope Mountains and to push the Ottomans to the south of the Arda River.

Meanwhile, the local commander of the area, Mehmed Yaver Pasha received orders from Mustafa Kemal, the commander of the Rhodope and Bulgarian Front, who had hastily come back into service splitting his honeymoon time in half, and was ordered to defend the first fortress city to allow reinforcements to arrive. Yaver Pasha had around 15,000 troops in the region, consisting largely of the 3rd Mountaineer Division. Meanwhile on the other hand, Ivanov had around 20,000 men consisting of the 2nd Thracian Division and the 40th Infantry Division converging on Kardzhali.

On April 2nd, 1915, the artillery regiments of the Bulgarians opened fire on the Ottoman fortifications which returned fire, beginning a massive cannonade between the two forces. Colonel Vasil Delov was ordered to take independent command of four columns and Delov took command as ordered. His four columns marched into the village of Kovancilar after defeating the small Ottoman garrison there, and started to heard for Kardzhali in a small flanking maneuver. Yaver Pasha hearing of this sent 3,000 troops under the command of Neshat Bey, the famous commander from the Italo-Ottoman War to counter attack against Delov and his troops and relieve the Ottoman flanks in the region.

After Neshat Bey drove the Bulgarians out of the villages surrounding Kardzhali, General Ivan Fichev, in total command of the Bulgarian Rhodope Front ordered General Ivanov to stop the advance of the 2nd Army against Kardzhali because the Bulgarians weren’t aware of the total Ottoman strength in the region. However, Ivanov did not withdraw his troops as ordered by the Bulgarian high command, and gave his officers autonomy and freedom of command and action. The detachment led by Delov counter attacked against Neshat Bey again and managed to retake some of the outlying villages. Neshat Bey managed to hold his ground and defend the flanks of the fortress however.

With that out of the way on April 4, Yaver Pasha received 1000 reinforcements and decided to take a risk and 10,000 Ottoman troops sallied out of the fortress lines and accompanied with artillery and cover fire, and attacked the Bulgarian positions. The Bulgarians were taken aback by the sudden attack, especially amidst torrential rain and the surprise factor, as well as the superior artillery that the Ottomans possessed with them pushed the Bulgarians out of Kardzhal for good.

a depiction of the Battle of Kardzhali

As the Ottomans won the first land engagement of the war, the Ottoman Black Sea Fleet also declared a blockade of the Tsardom of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Adriatic Fleet also declared a blockade of Montenegro, thus starting the war in absolute earnest.” The War in the Balkans: Ottoman Validation. Penguin Publishing, 2007.

***

The Ottomans are off to a good start. Trading some territory to secure Greek flank is absolutely worth it at this time. They need all the troops they can get to bear the brunt of the Balkan front, even when every preparation were miles better than OTL. Besides tying the Greeks into more codependency with OE economy would be a good thing. Would prevent them from getting any ideas of attacking their important economic partner.

Also, I don't know much about OTL WW1 details but seems the Germans are screwed more than OTL as they lost strategic territory and already angered Britain into war. The war might even be shorter this time.

Also, I don't know much about OTL WW1 details but seems the Germans are screwed more than OTL as they lost strategic territory and already angered Britain into war. The war might even be shorter this time.

no. Vlore and Durazzo is more than enough for the adriatic fleet.Will the Ottomans have basing rights at Port of preveza for naval warships ?

Indeed. To gain some you must lose some after all....The Ottomans are off to a good start. Trading some territory to secure Greek flank is absolutely worth it at this time.

Indeed. Making attacking each other economically ruinous is a good way to secure each other's bordersThey need all the troops they can get to bear the brunt of the Balkan front, even when every preparation were miles better than OTL. Besides tying the Greeks into more codependency with OE economy would be a good thing. Would prevent them from getting any ideas of attacking their important economic partner.

They are in a worse situation than otl that's for sure.Also, I don't know much about OTL WW1 details but seems the Germans are screwed more than OTL as they lost strategic territory and already angered Britain into war. The war might even be shorter this time.

indeed unfortunately.One mistake by Mustafa Kemal and he will be accused of conspiring with enemies because of his marriage.

Unlikely, I remember there's a chapter about Mustafa Kemal becoming Grand Vizier.One mistake by Mustafa Kemal and he will be accused of conspiring with enemies because of his marriage.

Threadmarks

View all 110 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Holidays in the Ottoman Empire Chapter 66: The Swedish Republic of Ostrobothnia & Growing Disillusionment Look into the future [4] Chapter 67: cultural update – The Top 3 Sports in the Ottoman Empire turtledoves 1926 Ottoman General Elections Map. Chapter 68: African Rumblings. Chapter 69: Land of the Unfree

Share: