Okay, hope this goes well. I'm a fanfiction reader, don't make fun of me, but have always particularly enjoyed Alternate History stories. That naturally led me here. Only found this site like a month ago, and decided to give it a try. I was originally going to do an alternate beginning for the colonization of the Americas, but eventually decided that it wasn't a particularly creative choice as an American myself. However my father grew up in Norway, and Norway is mainly famous for vikings, so here I am. I'll put a post afterwards so you'll actually have read my attempt.

Remember I'm new though. If I made some AH faux pas that I didn't know about or posted this wrong, please tell me. Hope you enjoy.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Rolf wasn’t scared to admit he breathed a sigh of relief when the storm finally dispersed. Near two decades of seafaring everywhere from Jutland to Ireland, trading with the kingdoms of Essex, Kent, Northumbria, Mercia, Gwynedd, Dyfed, Connacht, Ulaid, Mide, Neustria, and never had he seen a storm come on so quick. Never had he been so fearful that he’d met his end.

“Thank Ægir. He might be in a mood, but at least he didn’t send us into Rán’s grasp,” Rolf declared aloud. His fellows clearly agreed, as he heard more than a few thankful prayers to the gods. While wishing to join them, Rolf felt it more necessary he get their bearings. He quickly scouted the sky, both searching and trying to grasp just where the sudden storm had sent them. The gods seemed with them though as he saw something that made it irrelevant, he quickly pointed and shouted, “Birds.”

His crewmen quickly craned their heads to look for themselves, and indeed there were distant birds on the horizon. They didn’t need his command before they were taking their positions. Using oars, they rotated the knarr till the wind caught the sail, and then used them to create more speed in the direction of the birds. Where there were birds, there was land, and after that storm even Norsemen wished for land.

As they moved, Rolf turned to his mate. Arne was a small man for a Norsemen, but he’d always had a sense for navigation. If he also had a head for numbers and counting, he’d probably be the one in charge rather than Rolf. “Where you reckon we are?”

Arne hesitated for a bit before replying, “Not so sure. We were travelling northeast, and the storm sent us northwest.”

“We left Northumbria half a day before that storm caught us, and been flung around for a near a day. That means Pictland,” Rolf said.

Arne however shook his head before saying, “No. Too far north. We’d have to go half a day south for Pictland, and probably a bit west.”

“But there’s nothing north of Pictland,” Rolf pointed out, eyebrow furrowed.

“I know.”

Well, that was interesting. Nothing to do but nothing to do but wait now. Either Arne was wrong or…Rolf had no clue.

It only took a short time before they got close enough to see. It was certainly land. Islands?

“You ever heard of any islands north of Pictland, Arne?” Rolf asked without removing his eyes from the growing islands.

“No I haven’t,” Arne replied.

That was more than enough for Rolf to start thinking. While they didn’t know that these islands had never been settled, they were clearly isolated to the point that few if any knew of them. There was opportunity there. While Hordaland, Rolf’s home, along with other Norse held regions wasn’t exactly overpopulated, land was still previous. Plus, Rolf had always felt there was a certain…restlessness among the Norse compared to other peoples. If these lands were sparsely populated enough, Rolf was sure that more than a few second sons and their women would be willing to strike out if they could potentially build a life.

They’d disembark, get a quick lay of the land, and hopefully refill their freshwater. They’d then set off east to Hordaland where their cargo of wine and silk they’d picked up from Neustria would be sold for a good price. Then, if the information they got from the islands was promising enough, Rolf could present it at the next ting. He’d even wait for a lagting if necessary. There’d have to be a jarl or goði willing to head a group to settle them.

Although maybe one wasn’t necessary.

Rolf was a karl, freeman. A prosperous one, considering his merchant business. He had enough money saved away to support a small effort, maybe a few dozen if they contributed some. Maybe twice that if he could convince a few sons of prominent land-owners who would be able to provide a bit extra than the necessities. Rolf had spent long enough traveling that he wouldn’t mind settling down with his wife and children on a permanent basis. Successfully heading such a group to claim these islands could very well end up with him as a goði, if not a jarl.

Yes, that sounds very nice. Rolf fixed his eyes on the approaching islands even more intently. It might just be his future before him.

…He didn’t know just how right he was.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

The discovery of the Hjaltland Islands (Shetland Islands OTL) is generally the point by which modern historians discern the beginning of the Norse Age of Settlement. It is a major turning point for the Norse people, ironic considering it seemingly came about through luck. The merchant ship of Rolf the Lucky was sent off course from its projected path between modern Jórvík, then known as Eoforwic (York OTL), and Hordaland by a sudden storm, ending up on course with the Hjaltland Islands.

While the official date generally used for the discovery is 710 AD, the exact date remains debated. The earliest possible point of discovery is generally considered several years before the start of the 8th century, with 710 being the other end of the scale. 710 is used as it is almost universally accepted as the date by which the Norse had undoubtedly discovered the Hjaltland Islands.

This is due to the lack of information regarding the settling of Hjaltland. While the sagas written clearly state the story of their discovery, there is literally nothing regarding their actual settling. As these sagas were written at least a century after the events, it is possible that the specifics were lost. We do not know who led the settlement, how many people were among the initial colonists, the year it occurred, or even what was done with the indigenous population that archeological efforts show were there.

Thankfully, the sagas give us an amount of information after this that while scarce appears to be supported by archeological evidence gathered.

The discovery of the very loosely populated Hjaltland Islands showed the clear possibility to the Norse of similar such places having either been missed entirely or occupying such a peripheral role that they were considered irrelevant by the larger kingdoms of the British Isles. With Hjaltland being too small and rocky to support any truly significant population, the Norse settlers set out to see if there were any more such opportunities. The sagas speak of systematic exploration of the waters north of Pictland.

Exploration that quickly bore fruit. Supposedly, Færøerne (Faroe Islands OTL) was discovered in 720, and settled by 725. The Norse had also subsumed Orcades (Orkney OTL) to reform it as Orkneyjar, supposedly in the same 720-725 range as Færøerne. The Norse had known of the region before, but it had been inhabited by Picts. It was likely in the eagerness of the settlement; the settlers had chosen to ignore it being a part of Pictland. The sagas also tell us that the Norse settlers killed the males of the indigenous Picts, taking the women and children as thralls. This is in contrast to Færøerne, where the insignificant indigenous populace had seemingly been assimilated into the Norse settlers without conflict. The sagas state that Færøerne had been inhabited by Norse, thus implying it had been settled by Norse potentially centuries before, which assisting in a peaceful integration. In 728, Snæland (Iceland OTL) was discovered. By 750, only a few sparse settlers were in Snæland, primarily those exiles who had little choice but to endure the miserable cold and weather, the only ones as the entire population would remain in only a few hundred till roughly the last few decades of the 9th century when the Medieval Warm Period increased the amount of habitable land there. Another area of settlement started in 730, a more extensive one. Orkneyjar had received the bulk of Norse settlers due to its mild climate and fertile soil making it well suited for agriculture, compared to the other areas that more relied of fishing and raising animals. The same reckless settlement that allowed the settlement of Orkneyjar caused settlers to start settling northern Pictland (Caithness, Sutherland, and Ross OTL), violently overtaking the sparse Pict populace in a similar manner as they had Orkneyjar. The region would eventually be called Suðrland by the Norse. The question of why King Nechtan didn’t respond to this invasion is generally answered by the belief that he either didn’t know due to the difficult terrain of the Highlands causing poor communication or possibly the sparse Pict populace of the area being generally disregarded by the royal court, who wouldn’t have known the Norse as anything but raiders.

This brief period of expansion by the Norse only encouraged their drive for colonization. Now the Norse were encroaching and settling lands held by the kingdoms of Britain at the time, and this was likely the reason for the timely conquests by the Norse. Either luck or careful planning after information gathering allowed the Norse to claim territories at the ends of the kingdoms’ territories by using their focus on other conflicts to draw attention away from themselves.

The sagas claim the Norse started the conquest of the islands that would later by known as Far Graseyland, Graseyland being an amalgamation of gras meaning grassy or pasture and eyland meaning islands (Outer Hebrides OTL), in 735. These islands were under the control of the Gaelic kingdom Dál Riata, but Dál Riata was under attack by King Óengus of the Pict kingdom of Fortriu at the time. Dál Riata was defeated by 741, with Graseyland (Inner Hebrides OTL) being taken by Fortriu. By this time Óengus must have known of the Norse in Far Graseyland, but it appears he likely considered them a peripheral threat and instead conducted military campaigns against the Kingdom of Northumbria in 740 and then allied with Northumbria against the Britons of Alt Clut in 744, 750, and 756. It wasn’t until the Norse attacked Graseyland in 750, taking advantage of a devastating defeat of the Picts by the Britons where Óengus’ brother was killed, that Óengus turned his attention to them. He conducted a short campaign in 752 where he ‘scattered the raiders plaguing the west’ before pulling out. Whether exaggeration of his victories or simply the result of Norse reinforcements, the Norse steadily took over Graseyland in the subsequent years till Óengus set out to once again scatter the Norse in 757. This time he would find only defeat.

With Óengus heading with his forces to the west, the Norse attacked the Pict settlements on the eastern coast that made up Pictland. The terrain and dispersed nature of the Picts that previously aided them against any invaders only assisted the Norse. The disorganized Norse; lacking any strong central leadership, had a natural sense for unconventional warfare. Relying heavily on the element of surprise in ambushes and sudden raids, deceit, stealth, and ruthlessness were not considered cowardly to the Norse but simply practical. Norse raids of the time were often likened to ‘swarming bees’, with excellent communication and dispersed raiding groups proving capable of moving faster, encompassing a wider area, and devastating more land than a conventional force. Óengus rushed to the east when he found out, but the Norse had fled in the style that would soon become characteristic of them. Norse forces now approached from the west, attacking where Óengus wasn’t. Eventually these unconventional tactics ate away at Óengus’ forces, and undermined confidence in him. Óengus’ force was eventually decisively defeated and Óengus killed in 758 where the modern River South Esk met the sea (around Montrose OTL), when the forces of Óengus and allied forces of the Pict kingdom of Circinn were destroyed when a night raid by Norse forces from the sea drove them away from the coast where awaiting Norse raider bands flanked them. This defeat marked the turning point in the fall of Pictland to the Norse, resulting in total Norse control over Pictland (Central and northern Scotland OTL). The Norse quickly settled the devastated land, the few remaining Picts being in isolation or women and children willfully submitting to assimilation into Norse culture or taken as thralls.

The Norse didn’t only make an impact in Pictland during this time. In fact, arguably one of the most significant events in history happened in the same timeframe. A raid on the monastery of Lindisfarne in 758. The Anglo-Saxons had largely abandoned reliance on the sea as they settled, and eventually a great number of monasteries were established on islands, peninsulas, and river mouths where they were distanced from the interference and politics of the mainland. No Christians could ever imagine attacking a holy place either, so they were viewed as safe. The Norse obviously did not share this belief, and the Norse raiders were no doubt amazed that such a wealthy place was so vulnerable.

So, it was on June 8th in 758 that Norse raiders attacked Lindisfarne without warning. To the Norse, it was likely a peripheral act by a small group who saw an opportunity. Largely unimportant compared to their efforts to conquer and settle Pictland. To the Christians of Britain, it was an unimaginable act of violence and sacrilege. The raiders killed the monks or threw them into the sea, with some also carried off as thralls alongside some of the treasure of the monastery.

There was another factor that made the raid the turning point it would historically be attributed as. King Ceowulf had ruled the Kingdom of Northumbria from 729 to 737, when he abdicated to enter the monastery of Lindisfarne. The former king was killed in the raid. The newly crowned King Oswulf was murdered within the year by Æthelwald Moll, who usurped the throne. Northumbria was thus engulfed in a civil war for several years that prevented a direct reprisal against the Norse, but the mere knowledge that Ceowulf was so brutally killed made the raid more impactful in Northumbria and the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Several other monasteries had been raided by the Norse before this, most notably Iona, but it was ultimately the raid on Lindisfarne that captured the attention of Britain. Together with the news of Pictland’s fall, history would remember the raid of Lindisfarne as the start of the ‘Viking Age’. So, it was that an unimportant raid to the Norse reverberated through history.

Despite the taking of Pictland and former Dál Riata, the Norse Age of Settlement continued. Modern historians still debate the reasoning behind the aggressive expansion by the Norse of the time. Some believe the Norse were simply ‘riding the momentum’ from their previous victories, encouraged by their taking of Pictland. It is also suggested that subsequent expansion actually started out as mere raids by prominent Norse warlords that characterized the Vikings, and they only truly claimed and settled lands when they discovered just how unprepared the natives of these lands were in regard to resisting them. There is also evidence that supports the belief that Alt Clut and Northumbria would eventually lead invasions of Norse Pictland, and it was in Norse counterattacks that subsequent conquests were achieved. One factor that almost all historians believe played a role was an unparalleled population boom engulfing the Norse. The rumors regarding the discovery and settlement of Hjaltland, Færøerne, and Orkneyjar seemed to have spread through the scattered Norse population. This created an optimistic atmosphere that led to major population growth that far outstripped the amount of available land these areas provided. In which case the assaults on Far Graseyland, Graseyland, and Pictland were borne as much from necessity as optimism, as mass starvation would have resulted without the gaining of additional land. While undoubtedly a factor, historians instead argue the degree by which it was a factor. Whether it was the driving force behind the expansion or simply supported the expansion already occurring? Regardless, this population boom was essential in the Norse Age of Settlement as it provided the, honestly inconsequential beforehand, Norse the numbers of young men driven to gain land for settlement to support their wars of conquest.

It appears that conflict arose first between the Norse and the Britons of Alt Clut after the fall of Pictland. The famous viking warlord Gunnar Rolfson, the primary Norse leader credited with defeating Óengus and often ascribed as the son of Rolf the Lucky, inflicted a great defeat on the Britons in 760. A Norse force was then repulsed from Dumbarton Castle in 761. King Alhred of Northumbria led an invasion of Norse Pictland in 766, after deposing King Æthelwald Moll in 765. For the next century Northumbria would be the most persistent enemy of the Norse, a conflict largely driven by religious differences. Gunnar Rolfson is similarly credited with the decisive Norse victory in 780 where Dumbarton Castle was taken, arguably the defining moment of Norse conquest of Alt Clut that was finished by 782. Gunnar supposedly died of his wounds he sustained from the attack. The war with Northumbria was more contentious, with a ‘devastating defeat’ of a Norse force in Bernicia recorded in 771. However, the Norse gradually overwhelmed northern Northumbria, with Lothian being taken by the Norse in 774 when King Alhred was defeated by the legendary viking warrior Snorre Ailsson. This defeat led to King Alhred being deposed in Eoforwic (York OTL) and replaced by King Æthelred. Æthelred was no more successful against the Norse though, despite the capture and execution of Snorre Ailsson in 775, and was overthrown and exiled in 779. The succeeding King Ælwald succeeded in briefly pushing the Norse back, but was murdered ealdorman Sicga in 788 due to politics. King Osred in turn made peace with the Norse in his short reign between 789 and 790, but was exiled to the Isle of Man to be replaced by King Æthelred, who had returned from exile. The Norse attempted to put Osred back on the throne in 792, but he was apprehended and executed by Æthelred. This show by the Norse that they would be willing to support claimants to the Northumbrian throne appeared to have led to the de-escalation of warfare between Norse Pictland and Northumbria for several decades. These decades of near constant warfare led to the Norse gaining control of Alt Clut, and capturing the territories of Lothian, Galloway, and Rheged from Northumbria (Lothian, Dumfries and Galloway, and Cumbria OTL, totaling northwest England and all of Scotland bar the far southeast).

While no doubt the greatest number of Norse were focused on the wars on the mainland, other Norse focused on Ireland and some raiders pillaged coastal settlements far and wide in what would later be viewed as the characteristic acts of Vikings.

Norse activity in the Irish Sea was dominated by the legendary viking Ívarr. Ívarr is no doubt best known for the founding of then Dyflin (Dublin OTL), derived from the Irish Dubh Linn, which meant ‘black pool’. The traditional date of its founding according to the sagas is the winter of 740-741, when Norse overwintered there by establishing longphorts. These ship-fortresses served multiple purposes, firstly as early settlements and to facilitate travel and trade in the region before later acting as bases to conduct raids further inland. While many historians argue that the Norse likely only stayed there for a short time before leaving, and it would be reestablished later, if it did start then it would mean Dyflin was the first major settlement established by the Norse in the British Isles.

Ívarr is then assumed to have assisted in the taking of Graseyland, but reportedly participated little in the wars against Pictland, Alt Clut, and Northumbria besides in a peripheral role. He instead became the main Norse leader in the Irish Sea. In his role as the goði, chieftain, of Dyflin, Ívarr largely shaped early Norse-Gaelic relations. Generally, the first several decades of Norse settlements in Ireland, there had grown to be several Norse settlements throughout Ireland in Linns, Wexford, Waterford, Cork, and Limerick, were remarkably peaceful by the standards of early Norse settlement. They relied more on trade with the local Irish kingdoms, primarily in thralls/slaves taken from Dál Riata, Pictland, Alt Clut, and Northumbria.

Eventually violence would begin though. According to the sagas, violence broke out when Norse attempted to settle greater portions of Ireland around 770 due to the ongoing wars against Alt Clut and Northumbria on the mainland discouraging heavy Norse settlement of the area. The native Gaels naturally protested this. Ívarr was supposedly reluctant to go to war, but eventually had little choice but to lead the Norse in Ireland. The greatest Norse triumph occurred regarding the Kingdom of Ulaid in northeast Ireland, which they overran and took from the Northern Uí Néill. However, the Norse suffered a terrible defeat at the hand of Northern Uí Néill at Magh (Muff OTL) in 775. A subsequent attack on Norse Ulaid was highly successful, and for a time it seemed likely the Norse would be driven from northern Ireland.

Ívarr would manage to prevent this through two act which would greatly solidify Norse presence in the British Isles. Firstly, was the capture of the Isle of Mann in 776. While with little immediate effect on the Norse in Ireland, it was an important event in the wars against Alt Clut and Northumbria. From the Isle Norse raiders could easily attack Alt Clut from the south and Northumbria’s Rheged and Cumbria from the west, an allowance that the sagas attest to shifting the battle lines in a way that seemingly precipitated the fall of Dumbarton Castle in 780 and the loss of Rheged and Cumbria to the Norse. The Isle of Man would also become a pivotal location in the domination of the Irish Sea by Ívarr’s line. The second major accomplishment was Ívarr’s forging of an alliance with Southern Uí Néill, a different branch of the same dynasty as Northern Uí Néill that were the ceremonial overlords of Ireland as High Kings and their traditional rivals, in 777. Despite Norse settlement and Viking raids, Southern Uí Néill saw opportunity in the prosperity Norse trade offered and the damage their raids could inflict on their enemies. Ívarr had several of his sons and grandsons take Gaelic brides, and vice versa. This eventually stabilized Norse settlement, with viking raids primarily focused on Northern Uí Néill and trade bringing greater prosperity to the south and east of Ireland. This also heralded the immense cultural exchange that would create the Norse-Gaels, although Ulaid remained more strictly Norse, and have a great impact on the Norse roughly a century later. While this alliance would not last forever, the Norse settlements soon were participating in the intermittent warfare of the native Irish kingdoms like they were natives themselves and thus asserted growing Norse power on all of Ireland.

While Ívarr traditionally died in 788 at over sixty years of age, his acts would make a massive difference in the future. Ívarr’s line would eventually grow to dominate the Irish Sea in both territory and trade. The Uí Ímair line would go on to found the Kingdom of the Isles (largely same as OTL), which ruled Far Graseyland, Graseyland, the Kingdom of Dyflin, and the Isle of Man. These would later be called Suðreyjar, or ‘Southern Islands’, in comparison to the Norðreyjar islands of Hjaltland, Orkneyjar, and Færøerne, or ‘Northern Islands’. Most historians consider the Uí Ímair line the first Norse dynasty of the Medieval Ages.

While these events were undoubtedly the most crucial in forming the Norse power base so critical in later history, later folklore and Renaissance tales focused on a different series of events. For the Carolingian Empire began in contemporary times to the latter half of the Norse Age of Settlement. The Carolingian dynasty finally replaced the Merovingian dynasty under the rule of King Pepin the Short in 751. Pepin’s son would end up overshadowing Pepin. Charles the Great, more widely known as Charlemagne, would succeed his father in 768 as co-ruler with his brother, Carloman. Carloman’s death in 771 left Charlemagne the undisputed ruler of the Frankish Kingdom. Charlemagne would spend almost the entirety of his reign conducting warfare, spreading Christianity by the sword and expanding the Carolingian Empire into the strongest and most powerful European power since the Western Roman Empire.

The Norse fit in during the Saxon Wars Charlemagne conducted against the Germanic Saxons. The first campaign of the war would start in 773, repeatedly intersected by Charlemagne’s campaigns in Italy. In 776, the Saxon war leader, Widukind, fled to his wife’s home of Jutland to stay with the Dane king Sigfred. He would return to Saxony to lead a new rebellion in 782, partly brought about by the code of law instituted Charlemagne that was harsh on religious issues against the native paganism, but this time he was not alone.

For Eirik the Pagan would bring several Norse armies against the Franks. It is generally believed that the news of the viking raids against Christian monasteries and churches had spread throughout the surrounding lands, and Widukind sought out the seemingly anti-Christian Norse for assistance against Charlemagne. Obviously, he succeeded. The Norse reinforcements also seemingly encouraged King Sigfred. Overall, when rebellion broke out in 782, Widukind’s Saxons were joined by several armies of Norse and Danes.

The Norse split into two forces. One led by a viking named Ragnar landed in Frisian east of the Lauwers River. Charlemagne’s grandfather had taken everything west of the Lauwers around 733, and Charlamagne himself had subdued everything east of it in 772 before initiating the Saxon Wars. The Frisians rose up, and the assistance of the Norse immediately removed Frankish control. The Frisians west of the Lauwers also staging an uprising afterwards. A mass return to paganism by the Frisian population followed, with large influence by Norse paganism. Marauders and raiders burned churches, and priests were forced to flee south. The Frisians subsequently sent an army to aid Widukind in Saxony against the Franks, and the Norse forces returned to their ships to attack the Franks.

Eirik himself led the majority of the Norse to attack Paris, arguably the most important city of the Frankish subkingdom of Neustria. Forbidding his vikings to raid the banks of Seine as they sailed up it to prevent being slowed or Paris receiving advance warning, his force fell on Paris in a surprise attack. He successfully took the Paris, and even went so far as to occupy it as his base of operations for a time. Viking raiders ravaged the land around Paris, while their ships sent much of the loot north to Norse territory. This had the effect of forcing Charlemagne to turn west from Saxony towards Neustria, or risk having one of the core Frankish territories ravaged and possibly ferment rebellion against him.

This worked to the benefit of Widukind. Widukind had brought about the defeat of a Frank force at Süntel, and the Dane forces started a vicious campaign against the Obotrites by both land and sea. The Obotrites were a confederation of West Slavic tribes to the northeast of Saxony, who had assisted Charlemagne against the Saxons. These setbacks caused Charlemagne to execute 4,500 Saxons who had been caught practicing paganism even after reverting to Christianity, the Verden Massacre. However afterwards he turned west, moving through Austrasia to expel Eirik from Neustria.

Eirik’s forces offered a degree of resistance to Charlemagne’s forces, but fled by ship before any major battle could occur. Charlemagne marched into Paris with his forces without encountering resistance. Eirik was far from done however. His forces raided Bretons (Brittany OTL), a dependency of the Franks, and then captured Nantes. Meanwhile the Norse forces under Ragnar went further south and captured Bordeaux. While easily accessible targets for the vikings, it is also thought these attacks were specifically conducted in hopes of inciting rebellion in Aquitaine, where Charlemagne and his father had dealt with a number of rebellions for independence, and other recently conquered regions. While a rebellion did occur, forces loyal to Charlemagne repelled an attempt by Ragnar to sail up the Garonne to capture Toulouse. This encouraged the loyalists to hold out till Charlemagne split his forces into two and sent one down to reinforce his control of Aquitaine while he himself went back to Saxony. Ragnar abandoned Bordeaux in face of a Frankish siege, and sailed up to Nantes. Eirik left and then set out in a bold campaign to take Aachen, Charlemagne’s capital in Austrasia, in 784.

Eirik sailed up the Rhine, intending to take Cologne. He succeeded, but an unexpectedly high Frankish force inflicted heavy casualties. Eirik wasn’t deterred though, leaving a small force to hold Cologne while he led the majority to take Aachen. An attempt to take Aachen quickly resulted in a failed assault, and Eirik was forced to settle down into a siege. Meanwhile Ragnar had sailed his forces up the Loire to try and take Tours.

However, fortunes turned against the Norse. Charlemagne had quickly abandoned Saxony to reinforce Aachen. In a lightning march, Charlemagne’s forces closed on Cologne. Eirik’s forces learned of the march, but failed to flee in time. They were forced to hold Cologne against Charlemagne till the forces besieging Aachen returned. They did so barely but even then, the Norse weren’t capable of holding. After a vicious battle, Eirik was forced to lead the ragged remains of his forces in a flight down the Rhine. Meanwhile, Ragnar’s attempt to take Tours failed. Three assaults resulted in heavy casualties, and a subsequent counterattack retook Nantes.

The war fully turned, with the Norse never regaining their early momentum. Some estimates say that the Norse forces were fully cut in half from these defeats, and a number abandoned the campaign, led by Ragnar. Eirik however refused to flee, and gathered the remains of his forces. He landed his forces, and then marched them near Tournai. There he took a strong defensive position that all but abandoning any hope to escape. Charlemagne took the offer of battle that would remove the Norse from the conflict. The Battle of Tournai officially lasted six days, four of a standoff and then a furious assault by Frankish forces that the Norse held off for a full day before being overwhelmed the second. The Norse were slaughtered, the Franks took heavy casualties, and Eirik was captured. Charlemagne then had Eirik executed in Aachen in the winter of 774.

The Franks were surprised to find Eirik was a young man, reportedly only eighteen by the time of his execution. Many historians subscribe to the belief that Eirik was a son of Gunnar Rolfson, the legendary warlord who largely overran Alt Clut. It would explain both how such a young warrior could lead such a large force, and just where the Norse forces had come from. The fall of Alt Clut in 782 would have left many Norse warriors either to join the war against Northumbria or search for battles elsewhere to fight.

Early folklore and culture during the Norse Renaissance would immortalize Eirik as a pagan champion against the onslaught of Christianity, hence his name of Eirik the Pagan. He would also popularly be portrayed as the great contemporary rival of Charlemagne. Another popular story plot regarding Eirik is a theorized betrayal of Eirik by Widukind and Sigfred. The Saxons and Danes had stayed concentrated in Saxony and the east, Sigfred overrunning the Obotrites and Widukind waging war against the Christian Saxon tribes while gathering the pagan Saxons and fortifying northern Saxony. The most popular story states that the Saxons and Danes were supposed to send forces to meet Eirik at Cologne to help him take Aachen, but withheld their forces to focus on defeating the remaining Franks in Saxony when Charlemagne went west. The Battle of Tournai is in turn portrayed as a heroic sacrifice by the Norse forces under Eirik to both draw Charlemagne further from Saxony for a time and inflict heavy casualties on the Franks even if it meant their destruction to assist the Saxons and Danes.

History, how it so often is, presents a more dismal picture of Eirik. Rather than Charlemagne’s greatest rival, Eirik is rarely mentioned by name at the time. The only known decree by Charlemagne regarding the Norse calls them ‘bands of heathen raiders’, and simple numbers made them little more than a minor threat to Charlemagne. While certainly their ability to promote rebellions throughout the Frankish kingdoms was dangerous, the Norse themselves were limited in numbers enough that they could have defeated ten times their numbers and the Franks could have easily replaced their losses. After the war the only acts Charlemagne took against the Norse were a basic series of defenses against future Norse incursions or raids, that were partly successful later although ultimately irrelevant, and reopening trade with King Offa of Mercia in exchange for Mercia refusing to trade with the Norse. Ultimately little for a man of Charlemagne’s power and influence.

More evidence exists that portrays the image that Charlemagne viewed Widukind and Sigfred as the true threats of the Saxon Wars. Indeed, after Eirik’s execution Charlemagne signed the Treaty of Hamburg in 786 that split Saxony in two, northern pagan Saxony under Widukind and southern Christian Saxony under himself. Charlemagne seemingly believed Widukind and Sigfred too strong too easily defeat by this point and instead prioritized putting down the rebellions caused by the Norse campaigns and conquering territories to the east and south that would likely prove simpler and less contentious.

Eirik is instead generally viewed by historians in two ways. The first, and worse, view is that he was little more than a brutal and vicious raider. He primarily focused on sacking Frank towns and plundering the countryside, and refused to flee even if it meant destruction. The other version is that a young Norse eager to live up to his father’s achievements by winning battles and plunder, and sometimes considered little more than a pawn of Widukind and Sigfred to force Charlemagne to devote his attention to the west. The Battle of Tournai in turn is generally viewed as a result of poor communication or naivety, Eirik either not receiving permission to retreat by Widukind and Sigfred and thus fighting to the end or not receiving the permission in time to avoid destruction.

In fact, while beneficial to the Saxons and Danes, many historians view the Norse participation in the Saxon Wars as a serious strategic blunder for the Norse. If the Norse forces sent against Charlemagne were instead devoted to the war with Northumbria, there is genuine reason to believe that the Norse could have decisively defeated Northumbria and overrun all of northern England. If so, then Eirik would likely have severely harmed the Norse in the long term by participating in the Saxon Wars. So, if he joined for any other reason than the defense of paganism, one could argue that Eirik was an unsuccessful leader of the Norse.

Regardless of his actual historical importance or impact, much like the Raid of Lindisfarne is used to mark the beginning of the Viking Age, Eirik’s death is often used as the point by which the Norse Age of Settlement ended. The feverish, almost manic, expansion of the Norse largely came to an end, and with it the almost constant conflict. While the Norse would settle and conquer more land in the future, it was a more calculated and opportunistic type of expansion compared to the vicious butchery the early Norse conducted against the Pits of Pictland, Britons of Alt Clut, Gaels of Dal Riata, and Anglo-Saxons of Northumbria.

Instead, the Norse Age of Trade began in 885.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

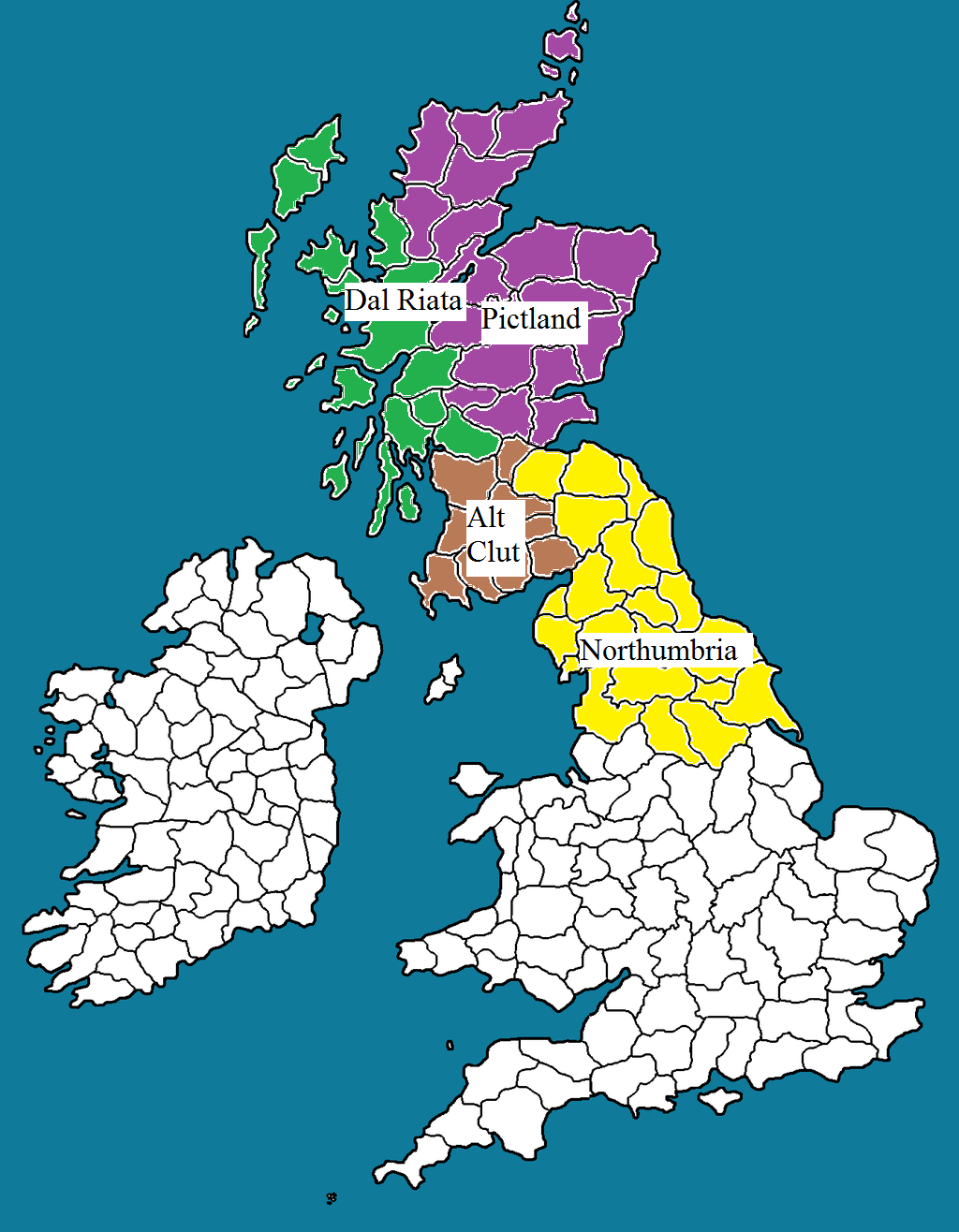

This is what you need to know of the northern kingdoms of Britain before the Norse arrived.

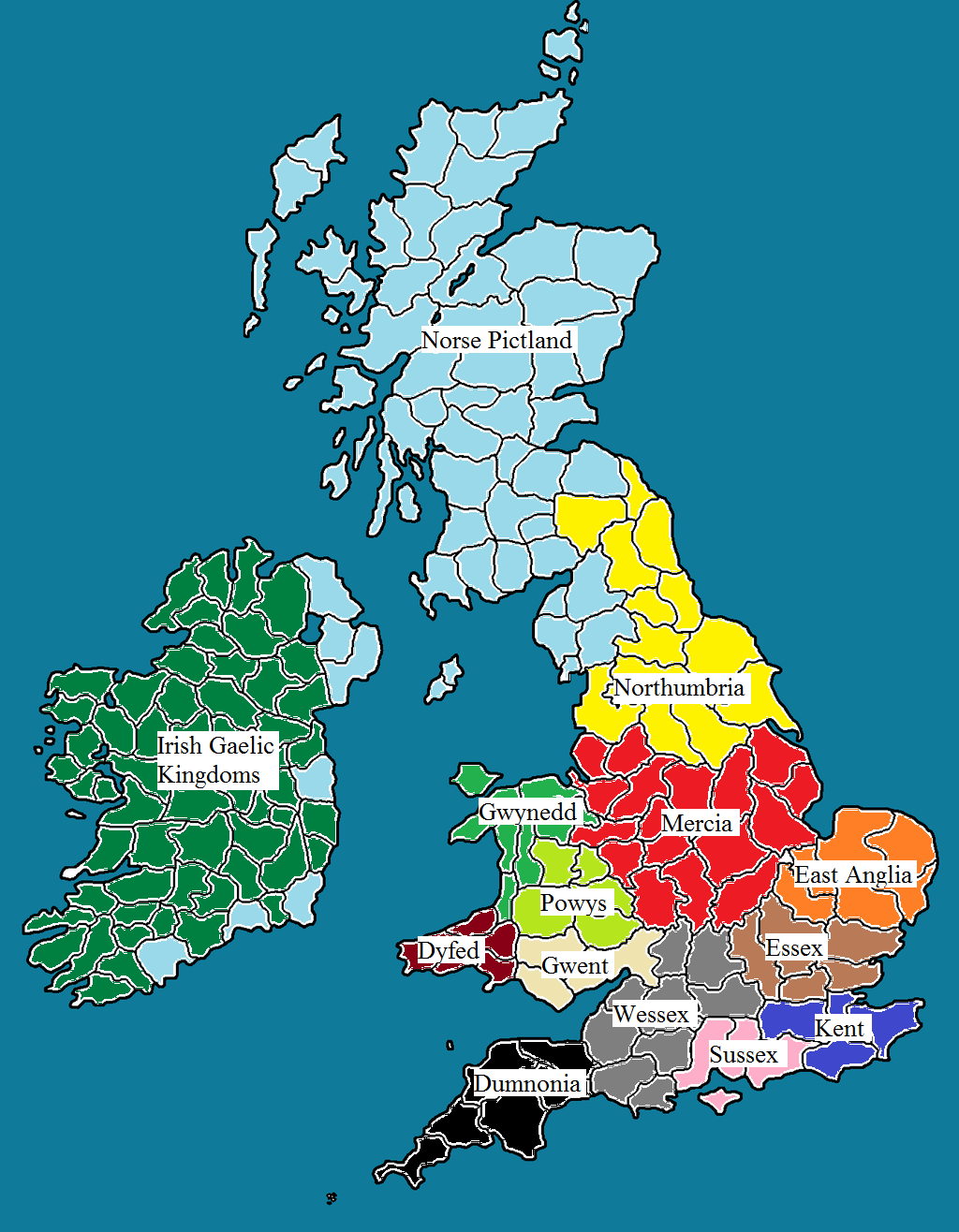

This is roughly the borders of the kingdoms of Britain at the end of the Norse Age of Settlement. Obviously, everything light blue is Norse territory. Remember that Scotland has roughly a fifth or sixth of the arable land as England, so the disparity in territory isn't quite as huge as the borders might imply. Northumbria was able to largely hold off the Norse.

I believe Mercia was the greatest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms at the time, and was probably the equal of the Norse.

I didn't define all the Irish Gaelic kingdoms as I'm having difficulty finding any maps from before 900 AD. If anyone wants, I'll do my best to give a rough map with as much accuracy as possible.

Remember I'm new though. If I made some AH faux pas that I didn't know about or posted this wrong, please tell me. Hope you enjoy.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Rolf wasn’t scared to admit he breathed a sigh of relief when the storm finally dispersed. Near two decades of seafaring everywhere from Jutland to Ireland, trading with the kingdoms of Essex, Kent, Northumbria, Mercia, Gwynedd, Dyfed, Connacht, Ulaid, Mide, Neustria, and never had he seen a storm come on so quick. Never had he been so fearful that he’d met his end.

“Thank Ægir. He might be in a mood, but at least he didn’t send us into Rán’s grasp,” Rolf declared aloud. His fellows clearly agreed, as he heard more than a few thankful prayers to the gods. While wishing to join them, Rolf felt it more necessary he get their bearings. He quickly scouted the sky, both searching and trying to grasp just where the sudden storm had sent them. The gods seemed with them though as he saw something that made it irrelevant, he quickly pointed and shouted, “Birds.”

His crewmen quickly craned their heads to look for themselves, and indeed there were distant birds on the horizon. They didn’t need his command before they were taking their positions. Using oars, they rotated the knarr till the wind caught the sail, and then used them to create more speed in the direction of the birds. Where there were birds, there was land, and after that storm even Norsemen wished for land.

As they moved, Rolf turned to his mate. Arne was a small man for a Norsemen, but he’d always had a sense for navigation. If he also had a head for numbers and counting, he’d probably be the one in charge rather than Rolf. “Where you reckon we are?”

Arne hesitated for a bit before replying, “Not so sure. We were travelling northeast, and the storm sent us northwest.”

“We left Northumbria half a day before that storm caught us, and been flung around for a near a day. That means Pictland,” Rolf said.

Arne however shook his head before saying, “No. Too far north. We’d have to go half a day south for Pictland, and probably a bit west.”

“But there’s nothing north of Pictland,” Rolf pointed out, eyebrow furrowed.

“I know.”

Well, that was interesting. Nothing to do but nothing to do but wait now. Either Arne was wrong or…Rolf had no clue.

It only took a short time before they got close enough to see. It was certainly land. Islands?

“You ever heard of any islands north of Pictland, Arne?” Rolf asked without removing his eyes from the growing islands.

“No I haven’t,” Arne replied.

That was more than enough for Rolf to start thinking. While they didn’t know that these islands had never been settled, they were clearly isolated to the point that few if any knew of them. There was opportunity there. While Hordaland, Rolf’s home, along with other Norse held regions wasn’t exactly overpopulated, land was still previous. Plus, Rolf had always felt there was a certain…restlessness among the Norse compared to other peoples. If these lands were sparsely populated enough, Rolf was sure that more than a few second sons and their women would be willing to strike out if they could potentially build a life.

They’d disembark, get a quick lay of the land, and hopefully refill their freshwater. They’d then set off east to Hordaland where their cargo of wine and silk they’d picked up from Neustria would be sold for a good price. Then, if the information they got from the islands was promising enough, Rolf could present it at the next ting. He’d even wait for a lagting if necessary. There’d have to be a jarl or goði willing to head a group to settle them.

Although maybe one wasn’t necessary.

Rolf was a karl, freeman. A prosperous one, considering his merchant business. He had enough money saved away to support a small effort, maybe a few dozen if they contributed some. Maybe twice that if he could convince a few sons of prominent land-owners who would be able to provide a bit extra than the necessities. Rolf had spent long enough traveling that he wouldn’t mind settling down with his wife and children on a permanent basis. Successfully heading such a group to claim these islands could very well end up with him as a goði, if not a jarl.

Yes, that sounds very nice. Rolf fixed his eyes on the approaching islands even more intently. It might just be his future before him.

…He didn’t know just how right he was.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

The discovery of the Hjaltland Islands (Shetland Islands OTL) is generally the point by which modern historians discern the beginning of the Norse Age of Settlement. It is a major turning point for the Norse people, ironic considering it seemingly came about through luck. The merchant ship of Rolf the Lucky was sent off course from its projected path between modern Jórvík, then known as Eoforwic (York OTL), and Hordaland by a sudden storm, ending up on course with the Hjaltland Islands.

While the official date generally used for the discovery is 710 AD, the exact date remains debated. The earliest possible point of discovery is generally considered several years before the start of the 8th century, with 710 being the other end of the scale. 710 is used as it is almost universally accepted as the date by which the Norse had undoubtedly discovered the Hjaltland Islands.

This is due to the lack of information regarding the settling of Hjaltland. While the sagas written clearly state the story of their discovery, there is literally nothing regarding their actual settling. As these sagas were written at least a century after the events, it is possible that the specifics were lost. We do not know who led the settlement, how many people were among the initial colonists, the year it occurred, or even what was done with the indigenous population that archeological efforts show were there.

Thankfully, the sagas give us an amount of information after this that while scarce appears to be supported by archeological evidence gathered.

The discovery of the very loosely populated Hjaltland Islands showed the clear possibility to the Norse of similar such places having either been missed entirely or occupying such a peripheral role that they were considered irrelevant by the larger kingdoms of the British Isles. With Hjaltland being too small and rocky to support any truly significant population, the Norse settlers set out to see if there were any more such opportunities. The sagas speak of systematic exploration of the waters north of Pictland.

Exploration that quickly bore fruit. Supposedly, Færøerne (Faroe Islands OTL) was discovered in 720, and settled by 725. The Norse had also subsumed Orcades (Orkney OTL) to reform it as Orkneyjar, supposedly in the same 720-725 range as Færøerne. The Norse had known of the region before, but it had been inhabited by Picts. It was likely in the eagerness of the settlement; the settlers had chosen to ignore it being a part of Pictland. The sagas also tell us that the Norse settlers killed the males of the indigenous Picts, taking the women and children as thralls. This is in contrast to Færøerne, where the insignificant indigenous populace had seemingly been assimilated into the Norse settlers without conflict. The sagas state that Færøerne had been inhabited by Norse, thus implying it had been settled by Norse potentially centuries before, which assisting in a peaceful integration. In 728, Snæland (Iceland OTL) was discovered. By 750, only a few sparse settlers were in Snæland, primarily those exiles who had little choice but to endure the miserable cold and weather, the only ones as the entire population would remain in only a few hundred till roughly the last few decades of the 9th century when the Medieval Warm Period increased the amount of habitable land there. Another area of settlement started in 730, a more extensive one. Orkneyjar had received the bulk of Norse settlers due to its mild climate and fertile soil making it well suited for agriculture, compared to the other areas that more relied of fishing and raising animals. The same reckless settlement that allowed the settlement of Orkneyjar caused settlers to start settling northern Pictland (Caithness, Sutherland, and Ross OTL), violently overtaking the sparse Pict populace in a similar manner as they had Orkneyjar. The region would eventually be called Suðrland by the Norse. The question of why King Nechtan didn’t respond to this invasion is generally answered by the belief that he either didn’t know due to the difficult terrain of the Highlands causing poor communication or possibly the sparse Pict populace of the area being generally disregarded by the royal court, who wouldn’t have known the Norse as anything but raiders.

This brief period of expansion by the Norse only encouraged their drive for colonization. Now the Norse were encroaching and settling lands held by the kingdoms of Britain at the time, and this was likely the reason for the timely conquests by the Norse. Either luck or careful planning after information gathering allowed the Norse to claim territories at the ends of the kingdoms’ territories by using their focus on other conflicts to draw attention away from themselves.

The sagas claim the Norse started the conquest of the islands that would later by known as Far Graseyland, Graseyland being an amalgamation of gras meaning grassy or pasture and eyland meaning islands (Outer Hebrides OTL), in 735. These islands were under the control of the Gaelic kingdom Dál Riata, but Dál Riata was under attack by King Óengus of the Pict kingdom of Fortriu at the time. Dál Riata was defeated by 741, with Graseyland (Inner Hebrides OTL) being taken by Fortriu. By this time Óengus must have known of the Norse in Far Graseyland, but it appears he likely considered them a peripheral threat and instead conducted military campaigns against the Kingdom of Northumbria in 740 and then allied with Northumbria against the Britons of Alt Clut in 744, 750, and 756. It wasn’t until the Norse attacked Graseyland in 750, taking advantage of a devastating defeat of the Picts by the Britons where Óengus’ brother was killed, that Óengus turned his attention to them. He conducted a short campaign in 752 where he ‘scattered the raiders plaguing the west’ before pulling out. Whether exaggeration of his victories or simply the result of Norse reinforcements, the Norse steadily took over Graseyland in the subsequent years till Óengus set out to once again scatter the Norse in 757. This time he would find only defeat.

With Óengus heading with his forces to the west, the Norse attacked the Pict settlements on the eastern coast that made up Pictland. The terrain and dispersed nature of the Picts that previously aided them against any invaders only assisted the Norse. The disorganized Norse; lacking any strong central leadership, had a natural sense for unconventional warfare. Relying heavily on the element of surprise in ambushes and sudden raids, deceit, stealth, and ruthlessness were not considered cowardly to the Norse but simply practical. Norse raids of the time were often likened to ‘swarming bees’, with excellent communication and dispersed raiding groups proving capable of moving faster, encompassing a wider area, and devastating more land than a conventional force. Óengus rushed to the east when he found out, but the Norse had fled in the style that would soon become characteristic of them. Norse forces now approached from the west, attacking where Óengus wasn’t. Eventually these unconventional tactics ate away at Óengus’ forces, and undermined confidence in him. Óengus’ force was eventually decisively defeated and Óengus killed in 758 where the modern River South Esk met the sea (around Montrose OTL), when the forces of Óengus and allied forces of the Pict kingdom of Circinn were destroyed when a night raid by Norse forces from the sea drove them away from the coast where awaiting Norse raider bands flanked them. This defeat marked the turning point in the fall of Pictland to the Norse, resulting in total Norse control over Pictland (Central and northern Scotland OTL). The Norse quickly settled the devastated land, the few remaining Picts being in isolation or women and children willfully submitting to assimilation into Norse culture or taken as thralls.

The Norse didn’t only make an impact in Pictland during this time. In fact, arguably one of the most significant events in history happened in the same timeframe. A raid on the monastery of Lindisfarne in 758. The Anglo-Saxons had largely abandoned reliance on the sea as they settled, and eventually a great number of monasteries were established on islands, peninsulas, and river mouths where they were distanced from the interference and politics of the mainland. No Christians could ever imagine attacking a holy place either, so they were viewed as safe. The Norse obviously did not share this belief, and the Norse raiders were no doubt amazed that such a wealthy place was so vulnerable.

So, it was on June 8th in 758 that Norse raiders attacked Lindisfarne without warning. To the Norse, it was likely a peripheral act by a small group who saw an opportunity. Largely unimportant compared to their efforts to conquer and settle Pictland. To the Christians of Britain, it was an unimaginable act of violence and sacrilege. The raiders killed the monks or threw them into the sea, with some also carried off as thralls alongside some of the treasure of the monastery.

There was another factor that made the raid the turning point it would historically be attributed as. King Ceowulf had ruled the Kingdom of Northumbria from 729 to 737, when he abdicated to enter the monastery of Lindisfarne. The former king was killed in the raid. The newly crowned King Oswulf was murdered within the year by Æthelwald Moll, who usurped the throne. Northumbria was thus engulfed in a civil war for several years that prevented a direct reprisal against the Norse, but the mere knowledge that Ceowulf was so brutally killed made the raid more impactful in Northumbria and the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Several other monasteries had been raided by the Norse before this, most notably Iona, but it was ultimately the raid on Lindisfarne that captured the attention of Britain. Together with the news of Pictland’s fall, history would remember the raid of Lindisfarne as the start of the ‘Viking Age’. So, it was that an unimportant raid to the Norse reverberated through history.

Despite the taking of Pictland and former Dál Riata, the Norse Age of Settlement continued. Modern historians still debate the reasoning behind the aggressive expansion by the Norse of the time. Some believe the Norse were simply ‘riding the momentum’ from their previous victories, encouraged by their taking of Pictland. It is also suggested that subsequent expansion actually started out as mere raids by prominent Norse warlords that characterized the Vikings, and they only truly claimed and settled lands when they discovered just how unprepared the natives of these lands were in regard to resisting them. There is also evidence that supports the belief that Alt Clut and Northumbria would eventually lead invasions of Norse Pictland, and it was in Norse counterattacks that subsequent conquests were achieved. One factor that almost all historians believe played a role was an unparalleled population boom engulfing the Norse. The rumors regarding the discovery and settlement of Hjaltland, Færøerne, and Orkneyjar seemed to have spread through the scattered Norse population. This created an optimistic atmosphere that led to major population growth that far outstripped the amount of available land these areas provided. In which case the assaults on Far Graseyland, Graseyland, and Pictland were borne as much from necessity as optimism, as mass starvation would have resulted without the gaining of additional land. While undoubtedly a factor, historians instead argue the degree by which it was a factor. Whether it was the driving force behind the expansion or simply supported the expansion already occurring? Regardless, this population boom was essential in the Norse Age of Settlement as it provided the, honestly inconsequential beforehand, Norse the numbers of young men driven to gain land for settlement to support their wars of conquest.

It appears that conflict arose first between the Norse and the Britons of Alt Clut after the fall of Pictland. The famous viking warlord Gunnar Rolfson, the primary Norse leader credited with defeating Óengus and often ascribed as the son of Rolf the Lucky, inflicted a great defeat on the Britons in 760. A Norse force was then repulsed from Dumbarton Castle in 761. King Alhred of Northumbria led an invasion of Norse Pictland in 766, after deposing King Æthelwald Moll in 765. For the next century Northumbria would be the most persistent enemy of the Norse, a conflict largely driven by religious differences. Gunnar Rolfson is similarly credited with the decisive Norse victory in 780 where Dumbarton Castle was taken, arguably the defining moment of Norse conquest of Alt Clut that was finished by 782. Gunnar supposedly died of his wounds he sustained from the attack. The war with Northumbria was more contentious, with a ‘devastating defeat’ of a Norse force in Bernicia recorded in 771. However, the Norse gradually overwhelmed northern Northumbria, with Lothian being taken by the Norse in 774 when King Alhred was defeated by the legendary viking warrior Snorre Ailsson. This defeat led to King Alhred being deposed in Eoforwic (York OTL) and replaced by King Æthelred. Æthelred was no more successful against the Norse though, despite the capture and execution of Snorre Ailsson in 775, and was overthrown and exiled in 779. The succeeding King Ælwald succeeded in briefly pushing the Norse back, but was murdered ealdorman Sicga in 788 due to politics. King Osred in turn made peace with the Norse in his short reign between 789 and 790, but was exiled to the Isle of Man to be replaced by King Æthelred, who had returned from exile. The Norse attempted to put Osred back on the throne in 792, but he was apprehended and executed by Æthelred. This show by the Norse that they would be willing to support claimants to the Northumbrian throne appeared to have led to the de-escalation of warfare between Norse Pictland and Northumbria for several decades. These decades of near constant warfare led to the Norse gaining control of Alt Clut, and capturing the territories of Lothian, Galloway, and Rheged from Northumbria (Lothian, Dumfries and Galloway, and Cumbria OTL, totaling northwest England and all of Scotland bar the far southeast).

While no doubt the greatest number of Norse were focused on the wars on the mainland, other Norse focused on Ireland and some raiders pillaged coastal settlements far and wide in what would later be viewed as the characteristic acts of Vikings.

Norse activity in the Irish Sea was dominated by the legendary viking Ívarr. Ívarr is no doubt best known for the founding of then Dyflin (Dublin OTL), derived from the Irish Dubh Linn, which meant ‘black pool’. The traditional date of its founding according to the sagas is the winter of 740-741, when Norse overwintered there by establishing longphorts. These ship-fortresses served multiple purposes, firstly as early settlements and to facilitate travel and trade in the region before later acting as bases to conduct raids further inland. While many historians argue that the Norse likely only stayed there for a short time before leaving, and it would be reestablished later, if it did start then it would mean Dyflin was the first major settlement established by the Norse in the British Isles.

Ívarr is then assumed to have assisted in the taking of Graseyland, but reportedly participated little in the wars against Pictland, Alt Clut, and Northumbria besides in a peripheral role. He instead became the main Norse leader in the Irish Sea. In his role as the goði, chieftain, of Dyflin, Ívarr largely shaped early Norse-Gaelic relations. Generally, the first several decades of Norse settlements in Ireland, there had grown to be several Norse settlements throughout Ireland in Linns, Wexford, Waterford, Cork, and Limerick, were remarkably peaceful by the standards of early Norse settlement. They relied more on trade with the local Irish kingdoms, primarily in thralls/slaves taken from Dál Riata, Pictland, Alt Clut, and Northumbria.

Eventually violence would begin though. According to the sagas, violence broke out when Norse attempted to settle greater portions of Ireland around 770 due to the ongoing wars against Alt Clut and Northumbria on the mainland discouraging heavy Norse settlement of the area. The native Gaels naturally protested this. Ívarr was supposedly reluctant to go to war, but eventually had little choice but to lead the Norse in Ireland. The greatest Norse triumph occurred regarding the Kingdom of Ulaid in northeast Ireland, which they overran and took from the Northern Uí Néill. However, the Norse suffered a terrible defeat at the hand of Northern Uí Néill at Magh (Muff OTL) in 775. A subsequent attack on Norse Ulaid was highly successful, and for a time it seemed likely the Norse would be driven from northern Ireland.

Ívarr would manage to prevent this through two act which would greatly solidify Norse presence in the British Isles. Firstly, was the capture of the Isle of Mann in 776. While with little immediate effect on the Norse in Ireland, it was an important event in the wars against Alt Clut and Northumbria. From the Isle Norse raiders could easily attack Alt Clut from the south and Northumbria’s Rheged and Cumbria from the west, an allowance that the sagas attest to shifting the battle lines in a way that seemingly precipitated the fall of Dumbarton Castle in 780 and the loss of Rheged and Cumbria to the Norse. The Isle of Man would also become a pivotal location in the domination of the Irish Sea by Ívarr’s line. The second major accomplishment was Ívarr’s forging of an alliance with Southern Uí Néill, a different branch of the same dynasty as Northern Uí Néill that were the ceremonial overlords of Ireland as High Kings and their traditional rivals, in 777. Despite Norse settlement and Viking raids, Southern Uí Néill saw opportunity in the prosperity Norse trade offered and the damage their raids could inflict on their enemies. Ívarr had several of his sons and grandsons take Gaelic brides, and vice versa. This eventually stabilized Norse settlement, with viking raids primarily focused on Northern Uí Néill and trade bringing greater prosperity to the south and east of Ireland. This also heralded the immense cultural exchange that would create the Norse-Gaels, although Ulaid remained more strictly Norse, and have a great impact on the Norse roughly a century later. While this alliance would not last forever, the Norse settlements soon were participating in the intermittent warfare of the native Irish kingdoms like they were natives themselves and thus asserted growing Norse power on all of Ireland.

While Ívarr traditionally died in 788 at over sixty years of age, his acts would make a massive difference in the future. Ívarr’s line would eventually grow to dominate the Irish Sea in both territory and trade. The Uí Ímair line would go on to found the Kingdom of the Isles (largely same as OTL), which ruled Far Graseyland, Graseyland, the Kingdom of Dyflin, and the Isle of Man. These would later be called Suðreyjar, or ‘Southern Islands’, in comparison to the Norðreyjar islands of Hjaltland, Orkneyjar, and Færøerne, or ‘Northern Islands’. Most historians consider the Uí Ímair line the first Norse dynasty of the Medieval Ages.

While these events were undoubtedly the most crucial in forming the Norse power base so critical in later history, later folklore and Renaissance tales focused on a different series of events. For the Carolingian Empire began in contemporary times to the latter half of the Norse Age of Settlement. The Carolingian dynasty finally replaced the Merovingian dynasty under the rule of King Pepin the Short in 751. Pepin’s son would end up overshadowing Pepin. Charles the Great, more widely known as Charlemagne, would succeed his father in 768 as co-ruler with his brother, Carloman. Carloman’s death in 771 left Charlemagne the undisputed ruler of the Frankish Kingdom. Charlemagne would spend almost the entirety of his reign conducting warfare, spreading Christianity by the sword and expanding the Carolingian Empire into the strongest and most powerful European power since the Western Roman Empire.

The Norse fit in during the Saxon Wars Charlemagne conducted against the Germanic Saxons. The first campaign of the war would start in 773, repeatedly intersected by Charlemagne’s campaigns in Italy. In 776, the Saxon war leader, Widukind, fled to his wife’s home of Jutland to stay with the Dane king Sigfred. He would return to Saxony to lead a new rebellion in 782, partly brought about by the code of law instituted Charlemagne that was harsh on religious issues against the native paganism, but this time he was not alone.

For Eirik the Pagan would bring several Norse armies against the Franks. It is generally believed that the news of the viking raids against Christian monasteries and churches had spread throughout the surrounding lands, and Widukind sought out the seemingly anti-Christian Norse for assistance against Charlemagne. Obviously, he succeeded. The Norse reinforcements also seemingly encouraged King Sigfred. Overall, when rebellion broke out in 782, Widukind’s Saxons were joined by several armies of Norse and Danes.

The Norse split into two forces. One led by a viking named Ragnar landed in Frisian east of the Lauwers River. Charlemagne’s grandfather had taken everything west of the Lauwers around 733, and Charlamagne himself had subdued everything east of it in 772 before initiating the Saxon Wars. The Frisians rose up, and the assistance of the Norse immediately removed Frankish control. The Frisians west of the Lauwers also staging an uprising afterwards. A mass return to paganism by the Frisian population followed, with large influence by Norse paganism. Marauders and raiders burned churches, and priests were forced to flee south. The Frisians subsequently sent an army to aid Widukind in Saxony against the Franks, and the Norse forces returned to their ships to attack the Franks.

Eirik himself led the majority of the Norse to attack Paris, arguably the most important city of the Frankish subkingdom of Neustria. Forbidding his vikings to raid the banks of Seine as they sailed up it to prevent being slowed or Paris receiving advance warning, his force fell on Paris in a surprise attack. He successfully took the Paris, and even went so far as to occupy it as his base of operations for a time. Viking raiders ravaged the land around Paris, while their ships sent much of the loot north to Norse territory. This had the effect of forcing Charlemagne to turn west from Saxony towards Neustria, or risk having one of the core Frankish territories ravaged and possibly ferment rebellion against him.

This worked to the benefit of Widukind. Widukind had brought about the defeat of a Frank force at Süntel, and the Dane forces started a vicious campaign against the Obotrites by both land and sea. The Obotrites were a confederation of West Slavic tribes to the northeast of Saxony, who had assisted Charlemagne against the Saxons. These setbacks caused Charlemagne to execute 4,500 Saxons who had been caught practicing paganism even after reverting to Christianity, the Verden Massacre. However afterwards he turned west, moving through Austrasia to expel Eirik from Neustria.

Eirik’s forces offered a degree of resistance to Charlemagne’s forces, but fled by ship before any major battle could occur. Charlemagne marched into Paris with his forces without encountering resistance. Eirik was far from done however. His forces raided Bretons (Brittany OTL), a dependency of the Franks, and then captured Nantes. Meanwhile the Norse forces under Ragnar went further south and captured Bordeaux. While easily accessible targets for the vikings, it is also thought these attacks were specifically conducted in hopes of inciting rebellion in Aquitaine, where Charlemagne and his father had dealt with a number of rebellions for independence, and other recently conquered regions. While a rebellion did occur, forces loyal to Charlemagne repelled an attempt by Ragnar to sail up the Garonne to capture Toulouse. This encouraged the loyalists to hold out till Charlemagne split his forces into two and sent one down to reinforce his control of Aquitaine while he himself went back to Saxony. Ragnar abandoned Bordeaux in face of a Frankish siege, and sailed up to Nantes. Eirik left and then set out in a bold campaign to take Aachen, Charlemagne’s capital in Austrasia, in 784.

Eirik sailed up the Rhine, intending to take Cologne. He succeeded, but an unexpectedly high Frankish force inflicted heavy casualties. Eirik wasn’t deterred though, leaving a small force to hold Cologne while he led the majority to take Aachen. An attempt to take Aachen quickly resulted in a failed assault, and Eirik was forced to settle down into a siege. Meanwhile Ragnar had sailed his forces up the Loire to try and take Tours.

However, fortunes turned against the Norse. Charlemagne had quickly abandoned Saxony to reinforce Aachen. In a lightning march, Charlemagne’s forces closed on Cologne. Eirik’s forces learned of the march, but failed to flee in time. They were forced to hold Cologne against Charlemagne till the forces besieging Aachen returned. They did so barely but even then, the Norse weren’t capable of holding. After a vicious battle, Eirik was forced to lead the ragged remains of his forces in a flight down the Rhine. Meanwhile, Ragnar’s attempt to take Tours failed. Three assaults resulted in heavy casualties, and a subsequent counterattack retook Nantes.

The war fully turned, with the Norse never regaining their early momentum. Some estimates say that the Norse forces were fully cut in half from these defeats, and a number abandoned the campaign, led by Ragnar. Eirik however refused to flee, and gathered the remains of his forces. He landed his forces, and then marched them near Tournai. There he took a strong defensive position that all but abandoning any hope to escape. Charlemagne took the offer of battle that would remove the Norse from the conflict. The Battle of Tournai officially lasted six days, four of a standoff and then a furious assault by Frankish forces that the Norse held off for a full day before being overwhelmed the second. The Norse were slaughtered, the Franks took heavy casualties, and Eirik was captured. Charlemagne then had Eirik executed in Aachen in the winter of 774.

The Franks were surprised to find Eirik was a young man, reportedly only eighteen by the time of his execution. Many historians subscribe to the belief that Eirik was a son of Gunnar Rolfson, the legendary warlord who largely overran Alt Clut. It would explain both how such a young warrior could lead such a large force, and just where the Norse forces had come from. The fall of Alt Clut in 782 would have left many Norse warriors either to join the war against Northumbria or search for battles elsewhere to fight.

Early folklore and culture during the Norse Renaissance would immortalize Eirik as a pagan champion against the onslaught of Christianity, hence his name of Eirik the Pagan. He would also popularly be portrayed as the great contemporary rival of Charlemagne. Another popular story plot regarding Eirik is a theorized betrayal of Eirik by Widukind and Sigfred. The Saxons and Danes had stayed concentrated in Saxony and the east, Sigfred overrunning the Obotrites and Widukind waging war against the Christian Saxon tribes while gathering the pagan Saxons and fortifying northern Saxony. The most popular story states that the Saxons and Danes were supposed to send forces to meet Eirik at Cologne to help him take Aachen, but withheld their forces to focus on defeating the remaining Franks in Saxony when Charlemagne went west. The Battle of Tournai is in turn portrayed as a heroic sacrifice by the Norse forces under Eirik to both draw Charlemagne further from Saxony for a time and inflict heavy casualties on the Franks even if it meant their destruction to assist the Saxons and Danes.

History, how it so often is, presents a more dismal picture of Eirik. Rather than Charlemagne’s greatest rival, Eirik is rarely mentioned by name at the time. The only known decree by Charlemagne regarding the Norse calls them ‘bands of heathen raiders’, and simple numbers made them little more than a minor threat to Charlemagne. While certainly their ability to promote rebellions throughout the Frankish kingdoms was dangerous, the Norse themselves were limited in numbers enough that they could have defeated ten times their numbers and the Franks could have easily replaced their losses. After the war the only acts Charlemagne took against the Norse were a basic series of defenses against future Norse incursions or raids, that were partly successful later although ultimately irrelevant, and reopening trade with King Offa of Mercia in exchange for Mercia refusing to trade with the Norse. Ultimately little for a man of Charlemagne’s power and influence.

More evidence exists that portrays the image that Charlemagne viewed Widukind and Sigfred as the true threats of the Saxon Wars. Indeed, after Eirik’s execution Charlemagne signed the Treaty of Hamburg in 786 that split Saxony in two, northern pagan Saxony under Widukind and southern Christian Saxony under himself. Charlemagne seemingly believed Widukind and Sigfred too strong too easily defeat by this point and instead prioritized putting down the rebellions caused by the Norse campaigns and conquering territories to the east and south that would likely prove simpler and less contentious.

Eirik is instead generally viewed by historians in two ways. The first, and worse, view is that he was little more than a brutal and vicious raider. He primarily focused on sacking Frank towns and plundering the countryside, and refused to flee even if it meant destruction. The other version is that a young Norse eager to live up to his father’s achievements by winning battles and plunder, and sometimes considered little more than a pawn of Widukind and Sigfred to force Charlemagne to devote his attention to the west. The Battle of Tournai in turn is generally viewed as a result of poor communication or naivety, Eirik either not receiving permission to retreat by Widukind and Sigfred and thus fighting to the end or not receiving the permission in time to avoid destruction.

In fact, while beneficial to the Saxons and Danes, many historians view the Norse participation in the Saxon Wars as a serious strategic blunder for the Norse. If the Norse forces sent against Charlemagne were instead devoted to the war with Northumbria, there is genuine reason to believe that the Norse could have decisively defeated Northumbria and overrun all of northern England. If so, then Eirik would likely have severely harmed the Norse in the long term by participating in the Saxon Wars. So, if he joined for any other reason than the defense of paganism, one could argue that Eirik was an unsuccessful leader of the Norse.

Regardless of his actual historical importance or impact, much like the Raid of Lindisfarne is used to mark the beginning of the Viking Age, Eirik’s death is often used as the point by which the Norse Age of Settlement ended. The feverish, almost manic, expansion of the Norse largely came to an end, and with it the almost constant conflict. While the Norse would settle and conquer more land in the future, it was a more calculated and opportunistic type of expansion compared to the vicious butchery the early Norse conducted against the Pits of Pictland, Britons of Alt Clut, Gaels of Dal Riata, and Anglo-Saxons of Northumbria.

Instead, the Norse Age of Trade began in 885.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

This is what you need to know of the northern kingdoms of Britain before the Norse arrived.

This is roughly the borders of the kingdoms of Britain at the end of the Norse Age of Settlement. Obviously, everything light blue is Norse territory. Remember that Scotland has roughly a fifth or sixth of the arable land as England, so the disparity in territory isn't quite as huge as the borders might imply. Northumbria was able to largely hold off the Norse.

I believe Mercia was the greatest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms at the time, and was probably the equal of the Norse.

I didn't define all the Irish Gaelic kingdoms as I'm having difficulty finding any maps from before 900 AD. If anyone wants, I'll do my best to give a rough map with as much accuracy as possible.

Last edited: