The Philippine Revolution (1824 - 1827)

Hey guys, so I'm rebooting this again, again. Here's the previous iteration, if y'all are interested. The main Point of Divergence is 1823, but as I wrote before, little changes have made this world a bit different from ours. Many thanks to those who encouraged me from the beginning to write this story, and to @ramones1986 for making the original flags.

Los Hijos del Pais v4

The Revolutionary Period (1823 – 1827)

The year is 1824, and it is the day of Saint Valentine in the Philippine Islands. Tensions between the Filipino Criollos and the Spanish government have been boiling for years, with many of the former feeling bitterness at being replaced by Peninsulars who know not the first thing of life on these isles, who have done nothing to earn their positions beyond being born two oceans away and connected to men in high places. There is a rot in Philippine society, from the Church controlled by Peninsular friars to the Civil Guard and bureaucracy whose highest officers are no longer sons of the land born and bred but distant and paranoiac proconsuls appointed by ignorant courtiers from Spain, themselves appointed by the Bourbon Ferdinand VII of Spain, a selfish, grasping figure unworthy of the title 'king', a man who makes his many fawning courtiers look positively enlightened. The liberal Cadiz Constitution of 1812, with all the rights and liberties that he promised to all citizens of the Spanish empire, was betrayed to absolutist rule, and since the Felon King's abysmal restoration in 1813, most of the Americas were lost to him, with only Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines left by 1823.

Yet even these distant isles would be lost to the Bourbon king, for as the years of his reign continued and the Americas were torn apart by revolution and civil war, the East Indies too boiled in tension against the Spaniards. In the north, the Ilocanos led by Salarogo Ambaristo and Pedro Mateo revolted against the wine monopoly imposed by the Spanish government in 1807, continuing a tradition of dissent begun by Diego and Gabriela Silang back in the days of the British occupation of Manila in the 1760s, and though it is ultimately crushed by 1808, the people of the region remember and resent the Spanish yoke. In the hills of Bohol, the revolt begun by Francisco Sendrijas, known more widely as Francisco Dagohoy, continued to fester as it had for decades since before Silang's revolt, and the banners of its Bohol Free State continue to fly in secret. And in 1820, an outbreak of cholera had caused riots and a massacre of foreigners in Manila and Cavite. But above all, a movement had risen among the Filipino Criollos and Tagalogs in the 1810s, a movement inspired by the hope of the Cadiz Constitution and sparked into organization and action by the outrages inflicted by the Peninsulars upon them since the restoration of King Ferdinand. This movement, begun by the Filipino patriot Count Luis Rodiguez Varela, given shape in the weekly publications of the Ramilette Patriotico, and most succinctly expressed in the 1821 tract El Indio Agraviado, had by the beginning of the 1820s hardened into a secret political organization called the Sons of the Nation, Los Hijos del Pais.

And this group, composed of many disenchanted Criollos and mestizos such as the Palmeros, the Bayots, and the Aranetas, had become stronger as the Spanish government continued to replace its officials and military officers with Peninsulars, driving many into the arms of the Sons of the Nation even as the governor-generals tried to root them out. This came to a head with the demotion of the Filipino-Mexican criollo Captain Andres Novales in 1823, a man of honor born in 1800 who fought with distinction in the Napoleonic wars as a teenager – rising to the position of Captain – but was demoted and commanded to fight against the Moro pirates in the south with a diminished station. This particular betrayal of a loyal Criollo in favor of supposedly more loyal men from the motherland was a turning point for the young man who had fought for King and Country, and he fell in with the Sons of the Nation on the way to his new assignment, supposedly meeting with the Palmero brothers in the days before his assignment.

And so, we return to the 14th of February 1824. It is the feast day of Saint Valentine, a day of lovers, and the day the once more promoted Captain Novales returns from campaigning in the south alongside Juan Fermin de San Martin, brother of the Argentine liberator Jose de San Martin. He brings with him his fellow soldiers and officers to celebrate the recovery of his former station. Unbeknownst to the Spanish government, however, he has also sent ahead of himself a number of messages to the Sons of the Nation, messages to prepare for the happenings of that day. The troops and officers he had gathered with him were among the disgruntled by the changes in the government of the East Indies, and they too were preparing.

And in the early morning of that day, the conspirators began their movements, seizing control of the armories and military posts within Intramuros and arresting key members of the Spanish government, including the incumbent governor-general Juan Antonio Martinez himself, and blessedly for the Sons of the Nation, the Valentine’s Day Coup goes quite smoothly. By high noon of that day, Fort Santiago had fallen with the help of Novales' brother Antonio, Martinez was in chains, the Spanish civil government had found itself decapitated, and Novales was promptly acclaimed Emperor of the Philippines, with his first decrees of independence and the founding of an Insular Assembly sent across the archipelago.

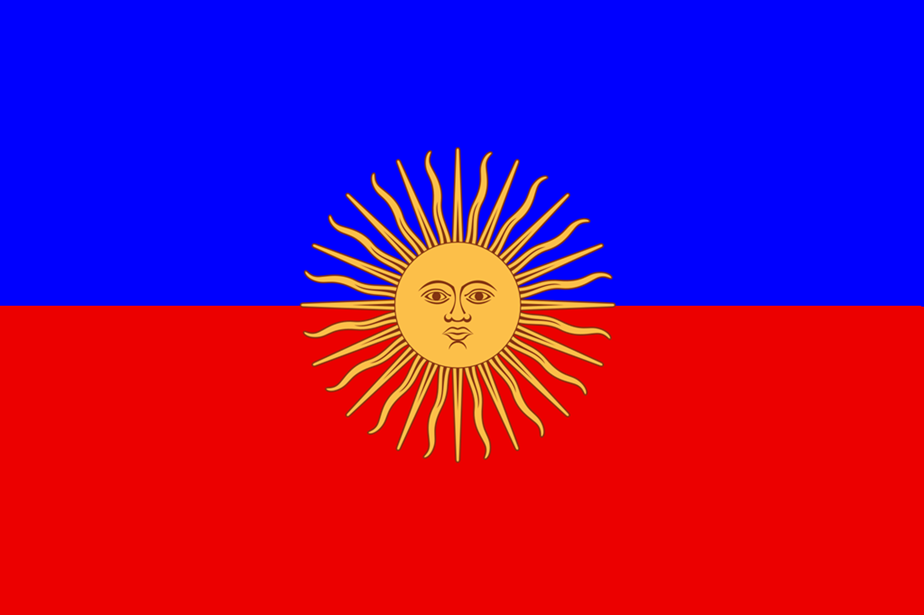

In the next couple of weeks which would be known as Bloody February, Martinez is executed alongside a number of the prominent loyalists taken into custody by the revolutionaries. As the flag of Spain is taken down from the flagpoles of Manila and its suburbs, two new flags rise in its place: that of a silver merlion bearing a sword on a red field, the flag of the Empire of the Philippines; and that of the golden Sun of May on a bicolor field of blue and red, the flag of the newly declared Insular Assembly, the flag of the Sons of the Nation, the flag of what would be the Republic of the Philippine Islands.

Flag of the First Empire of the Philippines (1824 - 1826)

Flag of the First Republic of the Philippines (1826 - ????)

Novales appoints the skilled administrator Marcelo Palmero as his prime minister to assemble his government and cabinet as the Insular Assembly prepares to write a constitution based on the Cadiz Constitution and gathers members and delegates from across the archipelago, most of them criollos and mestizos, but many of them natives or representatives of the Chinese community. In the meanwhile, the newly acclaimed Emperor assembles his fellow officers and marches north with the bulk of his forces to establish control of the Tagalog-Pampango heartland and the Cagayan valley as he sends his subordinate Alfonso Ruiz to secure the city of Cavite, itself already in revolt. Over the course of the next few weeks and months and all over the archipelago, those who receive the decrees of Novales are divided between a few loyalists and a number of revolutionary factions gaining momentum. Juan Fermin begins a revolt in Zamboanga, establishing the Zamboanga Free State, but is driven out from the city itself, forcing him to decamp in the hills and build support in the countryside. The region of Ilocos, which had been pacified less than two decades ago, once more convulses under the flag of the Basi revolt. The chaos in Luzon leads to a surge of Boholano rebels taking over their whole island in the name of the First Republic of Bohol, even as a few other principalia families assemble in other regions to establish their own local assemblies and send delegates to Manila, even as peasant farmers build their own communes and fight loyalist principalia families. And while the various revolutionary factions secure their regions, mutinies begin on the various squadrons and fleets as some agitate to fight for the revolution and its forces, the most notable being the mutiny of Venancio Adlao, a humble Indio seaman from the Visayas who would come to establish the Revolutionary Fleet and be the most famed naval commander of the Philippine Revolution.

In the midst of this chaos, loyalist leaders rally their forces in a contested Bicol and on the Central Plains of Luzon, and the Imperial Revolutionary Army of Novales fights a campaign to grind the latter loyalist force down by driving it to the west into Tarlac, culminating in the Battle of Camiling, which ends in a revolutionary victory. The Revolutionary Army of Southern Luzon assembled by Ruiz, on the other hand, prepares for a long slog in Bicol. By the end of the year, the Empire of the Philippines effectively controls most of central and southwestern Luzon, and many of the various free states and republics established by revolutionary forces have sent delegates to help assemble the 1824-1825 Federal Articles, which serve as a draft for the formal 1826 Constitution which itself takes as its model the Cadiz Constitution promulgated by Spain a few years before, as well as the American Constitution of the late 18th century.

As the nation convulses and fights itself, Palmero and his cabinet turn to deal with the Church, which is divided between friars and bishops of Spanish blood and the native secular priests. Some of the secular priests, already ill-trained and suspected of sedition by the organized Church, end up abandoning their vocation and joining the revolutionaries. More of them end up establishing lay brotherhoods and confraternities to maintain order in the confusion. The higher-ups in the Church are themselves divided between the Peninsular friars who remain loyal to Spain and the bishops, criollos, and mestizos who fight to keep the nation Catholic through the chaos of the revolution. The chaos of revolution even leads some to unorthodox practices and beliefs, with a few isolated mobs killing friars and despoiling monasteries suspected of abuse. In the first weeks of the revolution, the ruling Archbishop of Manila, the Dominican Juan Antonio Zulaibar, had passed away, and though there were accusations of foul play thrown by Spanish loyalists, Emperor Novales and his prime minister Palmero allayed fears by attending Mass performed by the interim Archbishop and guaranteeing for now the rights of the bishops, especially against the friars who would become the main pillar of resistance against the revolutionaries.

As 1825 begins, Novales marches northeast into the Cagayan Valley after securing the Ilocano Republic's loyalty to the Insular Assembly with a few communications with their delegates, while Ruiz marches east into Bicol, where he fights a campaign against the loyalists, culminating in the Battle of Naga. In Cagayan Valley, on the other hand, the emperor clears out the loyalists, including the friar orders who lead the resistance against the revolutionaries, and seizes their land. By the middle of the year, the valley is secure, and the emperor returns to Manila alongside Ruiz where the two are acclaimed for their triumphs against the tyrannical Spaniards. And so, the emperor begins learning of all the dealings of Palmero and the Assembly since his campaigns against the Spaniards. Here he decrees more laws and proclamations with the advice of Palmero and the Bayot family.

While Luzon is fully secured, Juan Fermin continues to fight the loyalists in Zamboanga, eventually retaking the city in April, and the Revolutionary Fleet ferries soldiers and delegates around the archipelago where they are needed. Cebu remains contested territory, its Spanish loyalists rendered impotent by the chaos in the city, while the Aranetas of Iloilo secure Panay island's loyalty to the revolutionary cause.

In the midst of all this, the Spanish government had sent a squadron to the Philippines to reinforce the few loyalists who yet remained, and by September the squadron has reached Philippine waters, but by then Venancio Adlao, now admiral of a sizable Revolutionary Fleet, has learned enough and gathered enough resources to meet them in battle. Still, Adlao fights a few difficult battles against the somewhat formidable Spanish squadron, but as if inspired by Our Lady of La Naval de Manila, the Revolutionary Fleet is able to defeat the squadron in the Battles of La Naval and proves victorious. And though the Dominicans seem shocked by the defeat of the loyalists, the people of Manila are jubilant at the sight of the Sun of May triumphant, and Adlao and his men walk barefoot to the shrine of Our Lady of the Rosary in thanks.

After this display of piety, Palmero himself organizes a sort of triumphal parade for the Emperor, his general, and his admiral, the three marching in glorious procession down the Calle Real del Palacio to the Cathedral of Manila and the Hall of the Insular Assembly which had once been the Governor's Palace. And here in the dying days of October, the delegates of the Assembly and Palmero's cabinet once more meet with the military officers who had fought for the independence of the nation, with their Emperor at their head. And here, the Emperor gives up his sword to Palmero, symbolically offering up his victories and acclamations to the Insular Assembly and abdicating his place as Emperor. He swears his allegiance to the Assembly alongside Ruiz and Adlao, and so ends the Empire of the Philippines.

Palmero thus becomes the head of the Provisional Government of the Philippines, which lasts a few months as the delegates and representatives draft the new constitution in Spanish and Tagalog and reorganize the various provinces and free states of the Philippines into more rational regions. The Revolutionary Fleet of Adlao, now flying the Sun of May standard, splits into several squadrons which are sent in different directions: one squadron, ferrying a criollo embassy headed by the Ilonggo criollo Buenaventura Araneta y de Dios, is sent to Europe; another, ferrying an embassy with more indios, is sent south to accept the surrender of the remaining loyalist garrisons after the defeat of the Spanish squadron, as well as to parley with the southern sultanates on their ambiguous status; and the last is sent with a small force to subjugate the Spanish garrisons of the Marianas and pick up Filipino exiles to return them to Manila.

By the end of the year, the 1826 Constitution is written in Spanish and Tagalog and signed into law, establishing the Republic of the Philippines, with delegates from across the archipelago ratifying it. Marcelo Palmero, the head of the Provisional Assembly, is elected as the head of government, the first President of the Philippines, and his first decrees, made with the advice of his peers, involve the establishment of the new order on the islands, and the disestablishment of the old order. With the establishment of a Bill of Rights, many of the old systems of tribute and forced labor are abolished alongside religious restrictions once enforced by the Catholic Church, and free trade slowly introduces the Philippines to the world market. By the 15th of March 1827 and after a long journey and weeks of negotiation, the embassy sent to Europe signs the Treaty of London, where – among other important countries – Britain, France, and the United States formally acknowledge the independence of the Republic, alongside many other Latin American countries. The Araneta Embassy also hires a number of merchants, teachers, and technical experts in various fields to help reform and rebuild the Philippine economy and society in the wake of the war of independence, even getting assistance from the Pope to assemble a number of teachers for a new system of public education in the republic in exchange for reestablishing the erudite Company of Jesus (or the Jesuits) on the Philippine Islands to balance out the conservative friar orders that had long become corrupt and in need of correction by the Holy Father.

While the Araneta Embassy accomplishes these tasks over the course of 1826 to 1827, the squadron carrying the Embassy to the Moros is able to spread the news of the Spanish defeats in Manila Bay and gather the surrenders of many remaining Spanish garrisons, most notably that of Zamboanga, which was one of the two major holdouts against the revolutionaries, the other being Cebu. Following these surrenders, the embassy makes its way to the Muslim south, where they plan to negotiate with the two sultans, Jamalul Kiram of Sulu and Iskandar Qudrallah Muhammad Zamal Ul-Azam – or Untong – of Maguindanao. Though both have a history of signing treaties of friendship with the Spaniards, there are tensions between the representatives of the newly independent government of Manila and the Muslims of the south, thus beginning weeks of hard negotiation and drafting of treaties. In the end, however, fear of other foreign powers like the British and the Dutch trump fear of the old devil that is the Manila government, and the two sultanates agree to become protectorates of the new republic. With this came the end of revolutionary period and the beginning of the experiment that is the Philippine Republic.

Los Hijos del Pais v4

The Revolutionary Period (1823 – 1827)

The year is 1824, and it is the day of Saint Valentine in the Philippine Islands. Tensions between the Filipino Criollos and the Spanish government have been boiling for years, with many of the former feeling bitterness at being replaced by Peninsulars who know not the first thing of life on these isles, who have done nothing to earn their positions beyond being born two oceans away and connected to men in high places. There is a rot in Philippine society, from the Church controlled by Peninsular friars to the Civil Guard and bureaucracy whose highest officers are no longer sons of the land born and bred but distant and paranoiac proconsuls appointed by ignorant courtiers from Spain, themselves appointed by the Bourbon Ferdinand VII of Spain, a selfish, grasping figure unworthy of the title 'king', a man who makes his many fawning courtiers look positively enlightened. The liberal Cadiz Constitution of 1812, with all the rights and liberties that he promised to all citizens of the Spanish empire, was betrayed to absolutist rule, and since the Felon King's abysmal restoration in 1813, most of the Americas were lost to him, with only Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines left by 1823.

Yet even these distant isles would be lost to the Bourbon king, for as the years of his reign continued and the Americas were torn apart by revolution and civil war, the East Indies too boiled in tension against the Spaniards. In the north, the Ilocanos led by Salarogo Ambaristo and Pedro Mateo revolted against the wine monopoly imposed by the Spanish government in 1807, continuing a tradition of dissent begun by Diego and Gabriela Silang back in the days of the British occupation of Manila in the 1760s, and though it is ultimately crushed by 1808, the people of the region remember and resent the Spanish yoke. In the hills of Bohol, the revolt begun by Francisco Sendrijas, known more widely as Francisco Dagohoy, continued to fester as it had for decades since before Silang's revolt, and the banners of its Bohol Free State continue to fly in secret. And in 1820, an outbreak of cholera had caused riots and a massacre of foreigners in Manila and Cavite. But above all, a movement had risen among the Filipino Criollos and Tagalogs in the 1810s, a movement inspired by the hope of the Cadiz Constitution and sparked into organization and action by the outrages inflicted by the Peninsulars upon them since the restoration of King Ferdinand. This movement, begun by the Filipino patriot Count Luis Rodiguez Varela, given shape in the weekly publications of the Ramilette Patriotico, and most succinctly expressed in the 1821 tract El Indio Agraviado, had by the beginning of the 1820s hardened into a secret political organization called the Sons of the Nation, Los Hijos del Pais.

And this group, composed of many disenchanted Criollos and mestizos such as the Palmeros, the Bayots, and the Aranetas, had become stronger as the Spanish government continued to replace its officials and military officers with Peninsulars, driving many into the arms of the Sons of the Nation even as the governor-generals tried to root them out. This came to a head with the demotion of the Filipino-Mexican criollo Captain Andres Novales in 1823, a man of honor born in 1800 who fought with distinction in the Napoleonic wars as a teenager – rising to the position of Captain – but was demoted and commanded to fight against the Moro pirates in the south with a diminished station. This particular betrayal of a loyal Criollo in favor of supposedly more loyal men from the motherland was a turning point for the young man who had fought for King and Country, and he fell in with the Sons of the Nation on the way to his new assignment, supposedly meeting with the Palmero brothers in the days before his assignment.

And so, we return to the 14th of February 1824. It is the feast day of Saint Valentine, a day of lovers, and the day the once more promoted Captain Novales returns from campaigning in the south alongside Juan Fermin de San Martin, brother of the Argentine liberator Jose de San Martin. He brings with him his fellow soldiers and officers to celebrate the recovery of his former station. Unbeknownst to the Spanish government, however, he has also sent ahead of himself a number of messages to the Sons of the Nation, messages to prepare for the happenings of that day. The troops and officers he had gathered with him were among the disgruntled by the changes in the government of the East Indies, and they too were preparing.

And in the early morning of that day, the conspirators began their movements, seizing control of the armories and military posts within Intramuros and arresting key members of the Spanish government, including the incumbent governor-general Juan Antonio Martinez himself, and blessedly for the Sons of the Nation, the Valentine’s Day Coup goes quite smoothly. By high noon of that day, Fort Santiago had fallen with the help of Novales' brother Antonio, Martinez was in chains, the Spanish civil government had found itself decapitated, and Novales was promptly acclaimed Emperor of the Philippines, with his first decrees of independence and the founding of an Insular Assembly sent across the archipelago.

In the next couple of weeks which would be known as Bloody February, Martinez is executed alongside a number of the prominent loyalists taken into custody by the revolutionaries. As the flag of Spain is taken down from the flagpoles of Manila and its suburbs, two new flags rise in its place: that of a silver merlion bearing a sword on a red field, the flag of the Empire of the Philippines; and that of the golden Sun of May on a bicolor field of blue and red, the flag of the newly declared Insular Assembly, the flag of the Sons of the Nation, the flag of what would be the Republic of the Philippine Islands.

Flag of the First Empire of the Philippines (1824 - 1826)

Flag of the First Republic of the Philippines (1826 - ????)

Novales appoints the skilled administrator Marcelo Palmero as his prime minister to assemble his government and cabinet as the Insular Assembly prepares to write a constitution based on the Cadiz Constitution and gathers members and delegates from across the archipelago, most of them criollos and mestizos, but many of them natives or representatives of the Chinese community. In the meanwhile, the newly acclaimed Emperor assembles his fellow officers and marches north with the bulk of his forces to establish control of the Tagalog-Pampango heartland and the Cagayan valley as he sends his subordinate Alfonso Ruiz to secure the city of Cavite, itself already in revolt. Over the course of the next few weeks and months and all over the archipelago, those who receive the decrees of Novales are divided between a few loyalists and a number of revolutionary factions gaining momentum. Juan Fermin begins a revolt in Zamboanga, establishing the Zamboanga Free State, but is driven out from the city itself, forcing him to decamp in the hills and build support in the countryside. The region of Ilocos, which had been pacified less than two decades ago, once more convulses under the flag of the Basi revolt. The chaos in Luzon leads to a surge of Boholano rebels taking over their whole island in the name of the First Republic of Bohol, even as a few other principalia families assemble in other regions to establish their own local assemblies and send delegates to Manila, even as peasant farmers build their own communes and fight loyalist principalia families. And while the various revolutionary factions secure their regions, mutinies begin on the various squadrons and fleets as some agitate to fight for the revolution and its forces, the most notable being the mutiny of Venancio Adlao, a humble Indio seaman from the Visayas who would come to establish the Revolutionary Fleet and be the most famed naval commander of the Philippine Revolution.

In the midst of this chaos, loyalist leaders rally their forces in a contested Bicol and on the Central Plains of Luzon, and the Imperial Revolutionary Army of Novales fights a campaign to grind the latter loyalist force down by driving it to the west into Tarlac, culminating in the Battle of Camiling, which ends in a revolutionary victory. The Revolutionary Army of Southern Luzon assembled by Ruiz, on the other hand, prepares for a long slog in Bicol. By the end of the year, the Empire of the Philippines effectively controls most of central and southwestern Luzon, and many of the various free states and republics established by revolutionary forces have sent delegates to help assemble the 1824-1825 Federal Articles, which serve as a draft for the formal 1826 Constitution which itself takes as its model the Cadiz Constitution promulgated by Spain a few years before, as well as the American Constitution of the late 18th century.

As the nation convulses and fights itself, Palmero and his cabinet turn to deal with the Church, which is divided between friars and bishops of Spanish blood and the native secular priests. Some of the secular priests, already ill-trained and suspected of sedition by the organized Church, end up abandoning their vocation and joining the revolutionaries. More of them end up establishing lay brotherhoods and confraternities to maintain order in the confusion. The higher-ups in the Church are themselves divided between the Peninsular friars who remain loyal to Spain and the bishops, criollos, and mestizos who fight to keep the nation Catholic through the chaos of the revolution. The chaos of revolution even leads some to unorthodox practices and beliefs, with a few isolated mobs killing friars and despoiling monasteries suspected of abuse. In the first weeks of the revolution, the ruling Archbishop of Manila, the Dominican Juan Antonio Zulaibar, had passed away, and though there were accusations of foul play thrown by Spanish loyalists, Emperor Novales and his prime minister Palmero allayed fears by attending Mass performed by the interim Archbishop and guaranteeing for now the rights of the bishops, especially against the friars who would become the main pillar of resistance against the revolutionaries.

As 1825 begins, Novales marches northeast into the Cagayan Valley after securing the Ilocano Republic's loyalty to the Insular Assembly with a few communications with their delegates, while Ruiz marches east into Bicol, where he fights a campaign against the loyalists, culminating in the Battle of Naga. In Cagayan Valley, on the other hand, the emperor clears out the loyalists, including the friar orders who lead the resistance against the revolutionaries, and seizes their land. By the middle of the year, the valley is secure, and the emperor returns to Manila alongside Ruiz where the two are acclaimed for their triumphs against the tyrannical Spaniards. And so, the emperor begins learning of all the dealings of Palmero and the Assembly since his campaigns against the Spaniards. Here he decrees more laws and proclamations with the advice of Palmero and the Bayot family.

While Luzon is fully secured, Juan Fermin continues to fight the loyalists in Zamboanga, eventually retaking the city in April, and the Revolutionary Fleet ferries soldiers and delegates around the archipelago where they are needed. Cebu remains contested territory, its Spanish loyalists rendered impotent by the chaos in the city, while the Aranetas of Iloilo secure Panay island's loyalty to the revolutionary cause.

In the midst of all this, the Spanish government had sent a squadron to the Philippines to reinforce the few loyalists who yet remained, and by September the squadron has reached Philippine waters, but by then Venancio Adlao, now admiral of a sizable Revolutionary Fleet, has learned enough and gathered enough resources to meet them in battle. Still, Adlao fights a few difficult battles against the somewhat formidable Spanish squadron, but as if inspired by Our Lady of La Naval de Manila, the Revolutionary Fleet is able to defeat the squadron in the Battles of La Naval and proves victorious. And though the Dominicans seem shocked by the defeat of the loyalists, the people of Manila are jubilant at the sight of the Sun of May triumphant, and Adlao and his men walk barefoot to the shrine of Our Lady of the Rosary in thanks.

After this display of piety, Palmero himself organizes a sort of triumphal parade for the Emperor, his general, and his admiral, the three marching in glorious procession down the Calle Real del Palacio to the Cathedral of Manila and the Hall of the Insular Assembly which had once been the Governor's Palace. And here in the dying days of October, the delegates of the Assembly and Palmero's cabinet once more meet with the military officers who had fought for the independence of the nation, with their Emperor at their head. And here, the Emperor gives up his sword to Palmero, symbolically offering up his victories and acclamations to the Insular Assembly and abdicating his place as Emperor. He swears his allegiance to the Assembly alongside Ruiz and Adlao, and so ends the Empire of the Philippines.

Palmero thus becomes the head of the Provisional Government of the Philippines, which lasts a few months as the delegates and representatives draft the new constitution in Spanish and Tagalog and reorganize the various provinces and free states of the Philippines into more rational regions. The Revolutionary Fleet of Adlao, now flying the Sun of May standard, splits into several squadrons which are sent in different directions: one squadron, ferrying a criollo embassy headed by the Ilonggo criollo Buenaventura Araneta y de Dios, is sent to Europe; another, ferrying an embassy with more indios, is sent south to accept the surrender of the remaining loyalist garrisons after the defeat of the Spanish squadron, as well as to parley with the southern sultanates on their ambiguous status; and the last is sent with a small force to subjugate the Spanish garrisons of the Marianas and pick up Filipino exiles to return them to Manila.

By the end of the year, the 1826 Constitution is written in Spanish and Tagalog and signed into law, establishing the Republic of the Philippines, with delegates from across the archipelago ratifying it. Marcelo Palmero, the head of the Provisional Assembly, is elected as the head of government, the first President of the Philippines, and his first decrees, made with the advice of his peers, involve the establishment of the new order on the islands, and the disestablishment of the old order. With the establishment of a Bill of Rights, many of the old systems of tribute and forced labor are abolished alongside religious restrictions once enforced by the Catholic Church, and free trade slowly introduces the Philippines to the world market. By the 15th of March 1827 and after a long journey and weeks of negotiation, the embassy sent to Europe signs the Treaty of London, where – among other important countries – Britain, France, and the United States formally acknowledge the independence of the Republic, alongside many other Latin American countries. The Araneta Embassy also hires a number of merchants, teachers, and technical experts in various fields to help reform and rebuild the Philippine economy and society in the wake of the war of independence, even getting assistance from the Pope to assemble a number of teachers for a new system of public education in the republic in exchange for reestablishing the erudite Company of Jesus (or the Jesuits) on the Philippine Islands to balance out the conservative friar orders that had long become corrupt and in need of correction by the Holy Father.

While the Araneta Embassy accomplishes these tasks over the course of 1826 to 1827, the squadron carrying the Embassy to the Moros is able to spread the news of the Spanish defeats in Manila Bay and gather the surrenders of many remaining Spanish garrisons, most notably that of Zamboanga, which was one of the two major holdouts against the revolutionaries, the other being Cebu. Following these surrenders, the embassy makes its way to the Muslim south, where they plan to negotiate with the two sultans, Jamalul Kiram of Sulu and Iskandar Qudrallah Muhammad Zamal Ul-Azam – or Untong – of Maguindanao. Though both have a history of signing treaties of friendship with the Spaniards, there are tensions between the representatives of the newly independent government of Manila and the Muslims of the south, thus beginning weeks of hard negotiation and drafting of treaties. In the end, however, fear of other foreign powers like the British and the Dutch trump fear of the old devil that is the Manila government, and the two sultanates agree to become protectorates of the new republic. With this came the end of revolutionary period and the beginning of the experiment that is the Philippine Republic.

Last edited: