Update: I've made a few more tweaks to the timeline, including a new image and captions for the photos.

I don't have time to put all of this into the Wiki page (thanks to E of Pi for setting that up). But "newbies" or veteran readers wanting to get up to speed on just what's happened in the first two decades of this timeline before the launch of Part III later today can rely on this for a quick assessment of where things stand. Of course, there's no complete substitute for reading the actual installments themselves at the Wiki page:

http://wiki.alternatehistory.com/doku.php/timelines/list_of_eyes_turned_skyward_posts

If it is not obvious, actual events of

our own timeline are placed in italics; events of the ETS timeline are in regular typeface. American manned missions are in

boldface; Soviet missions of note are in

red typeface. Per the authors' clarifications, I'm assuming no butterflies to avert the major events in subsequent years (Fall of Saigon, Fall of Berlin Wall, Gulf War, etc.), a few of which I have added here and there to put these Space Race developments in context.

If I have made any mistakes, I look forward to being corrected. Hope this helps everyone get a quick idea of where things stand as Part III picks up in the middle of the first Bush Administration (ca. 1990).

______________________________________________

Eyes Turned Skywards:

A Timeline

"When once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return."

--Commonly attributed to Leonardo da Vinci

1967

Jan 1967:

Apollo I crew of Gus Grissom, Roger Chaffee, and Ed White is killed by fire caused by faulty wiring during a "plugs-out" test on launchpad, triggering a two month investigation and thorough redesign of the Apollo command module

Apr 1967:

Soyuz I ends in disaster as V. Komarov is killed when his troubled Soyuz capsule crashes on landing, forcing a reassessment of the Soyuz program to parallel Apollo's trial

Nov 1967:

Apollo 4 - First test launch of Saturn V rocket

Dec 1967: Successful flight of Europa F07, a test launch for the Coralie upper stage carrying a dummy third stage

[AUXILIARY POINT OF DEPARTURE]

1968

Jan 1968:

Apollo 5 - First unmanned, Earth orbital flight test of LM, launched on Saturn IB

Apr 1968:

Apollo 6 - unmanned test flight of Saturn V; Debut of Stanley Kubrick's groundbreaking "2001: A Space Odyssey"

Aug 1968:

NASA Director James Webb halts production of the Saturn V after AS-515 as a response to congressional budget cuts, especially to the Apollo Applications Program (AAP)

Sep 1968:

Soviet Union successfully launches and recovers unmanned Zond 5 for circumlunar flight, sending tortoises where no chelonian has ever gone before

Oct 1968:

Apollo 7 successfully tests Apollo CM and SM in Earth orbit (Schirra, Cunningham, Eisele). NASA Director James Webb steps down after shepherding NASA through its eight most critical years; Thomas Paine is appointed interim Administrator of NASA by the outgoing Johnson Administration

Oct 1968:

Soyuz 3 orbital mission (G. Beregovoi)

Nov 1968:

Election of Richard M. Nixon as President of the United States; Successful launch of Europa F08 on Nov. 26, the first test of the complete Europa 1 vehicle by ELDO, the European Launcher Development Organization;

Zond 6 unmanned mission on circumlunar flight, crashes on reentry

Dec 1968:

Apollo 8 becomes the first manned mission to leave Earth orbit, returning after completing ten orbits around the Moon on Christmas Day (Borman, Lovell, Anders)

The New Boss Takes Charge

The first Apollo 11 sample return container, containing lunar surface material,

arrives at Ellington Air Force Base, held by new NASA Administrator George Low (far left)

1969

Jan 1969:

Soyuz 4 and Soyuz 5 achieve docking in low earth orbit (V. Shatalov, A. Yeliseyev, Ye. Khrunov, B. Volynov)

Jan 1969:

New Director of the Bureau of the Budget, Robert Mayo, writes a government-wide letter to those heads of agencies on January 23, asking them to review their portions of President Johnson's FY 1970 budget and to propose areas where spending might be reduced. Outgoing Administrator Paine urges a budget increase for NASA; [/i]other NASA chiefs, including George Low, are concerned that this is unrealistic

Feb 1969:

Incoming President Richard Nixon decides to appoint NASA Deputy Administrator Dr. George M. Low as Administrator of NASA to replace Interim Administrator Thomas Paine [POINT OF DEPARTURE]

Feb 1969:

NBC announces cancellation of "Star Trek" television series, citing low ratings

Mar 1969:

Apollo 9 successfully tests out Lunar Module (LM) in low earth orbit (McDivitt, Scott, Schweickart)

Apr 1969:

New Air Force Secretary Robert Seamans urges examination of a reusable space plane option to George Low, who reacts skeptically, concerned about its feasibility and cost

May 1969:

Apollo 10 successfully tests out LM in lunar orbit, flying to within 8.4 nm of lunar surface (Stafford, Young, Cernan)

Jun 1969: George Low officially confirmed as new Administrator of NASA by U.S. Senate; President Nixon asks the National Aeronautics and Space Council, chaired by his Vice-President Spiro Agnew, to develop and present a plan for NASA's future; Low begins drafting post-Apollo plans for NASA in earnest, focusing increasingly on space station options: Air Force cancels Manned Orbiting Laboratory military space station project, allowing seven of its 14 designated astronauts to join NASA

Jun 1969:

Soviet Luna E-8-5 No.402 makes first attempt at lunar sample return, destroyed after upper stage failure

Jul 1969:

Explosion of Soviet N-1 booster 9 seconds into test flight at Baikonur launch facility, resulting in one of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions in human history

July 1969:

Apollo 11 performed the first manned landing on the Moon in the Sea of Tranquility, fulfilling the mandate of President Kennedy (Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins); Final plan for AAP (Skylab) tentatively decided: one Saturn-V, three Saturn IB rockets for launch and crew delivery of "dry" orbital workshop

Aug 1969:

Mariner 6 and 7 successfully complete flybys of Mars

Oct 1969:

Joint Mission of Soyuz 6, 7 and 8 in low earth orbit (G. Shonin, V. Kubasov, A. Filipchenko, V. Volkov, V. Gorbatko, V. Shatalov, A. Yeliseyev)

Nov 1969:

Apollo 12 performed the first precise manned landing on the Moon in the Ocean of Storms near the Surveyor 3 probe. (Conrad, Gordon, Bean)

1970

Jan 1970:

NASA decides that Apollo 20 will be cancelled, allowing SA-514 to be assigned to launch Skylab, America's first space station, in 1972

Apr 1970:

Apollo 13 aborted after an SM oxygen tank exploded on the trip to the moon, causing the landing to be cancelled, leading to a dramatic "successful failure" recovery of the crew (Lovell, Swigert, Haise); People's Republic of China launches its first satellite, Dongfanghong I on a Long March I rocket (CZ-1)

Jun 1970:

Soyuz 9 attempts endurance test in low earth orbit (A. Nikolayev, V. Sevastyanov); Vladimir Chelomei finally able to obtain a formal go-ahead for development of the TKS ferry to Almaz military space stations

Aug 1970:

Soviet Venera 7 becomes first spacecraft ever to land on another planet, touching down on Venus, going silent shortly after touchdown

Sep 1970: NASA decides that Apollo 15 will be cancelled, allowing SA-515 to be assigned to the followup space station to Skylab; Apollo 16, 17, 18, and 19 are renumbered 15-18, all "J-Class" Missions

Oct 1970: Having decided to focus future NASA manned efforts on low earth orbit space stations, Administrator George Low receives approval to begin design work on

Saturn IC, the successor to the Saturn IB and V rockets, using upgraded F1-A engine; as well as approval to begin design work for

Apollo CM Block III and Autonomous Automated Rendezvous and Docking Vehicle (

AARDV) for station resupply. Soviet Academy of Sciences president Mstislav Keldysh responds to NASA Administrator George Low letter proposing a project about a cooperative space mission, eventually to become the Apollo-Soyuz Test Projects

1971

Jan 1971:

Apollo 14 landed successfully at Fra Mauro, delivering first color video images from the surface of the Moon, first materials science experiments in space, and one legendary golf shot (Shepard, Roosa, Mitchell)

Apr 1971:

Soyuz 10 attempts failed docking with Salyut 1, the world's first space station (V. Shatalov A. Yeliseyev, N. Rukavishnikov)

Jun 1971:

Soyuz 11 succeeds in docking with Salyut 1, but all three astronauts die tragically on reentry (G. Dobrovolski, V. Patsayev, V. Volkov); third Soviet N-1 rocket test launch fails

July 1971:

Apollo 15 lands at Hadley-Apennine as the first "J series" mission with a 3-day lunar stay and extensive geology investigations; First use of the Lunar Roving Vehicle (Scott, Worden, Irwin)

1972

??? 1972: European Space Research Organization (ESRO) and the European Launcher Development Organization (ELDO) merge to form the European Space Agency

Mar 1972:

Launch of Pioneer 10 space probe to Jupiter

Apr 1972:

Apollo 16 lands in the Descartes Highlands, completing 3 lunar EVAs using lunar rover and deep space EVA (Young, Mattingly, Duke). President Nixon and Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev sign Agreement Concerning Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes, clearing the way for Apollo Soyuz missions

May 1972:

Wernher von Braun retires as head of the Marshall Space Flight Center

Nov 1972:

Fourth and final Soviet N-1 rocket test fails

Dec 1972:

Apollo 17 lands at Taurus-Littrow after first night launch, completing three EVAs using lunar rover (Cernan, Evans, Engle); Vasiliy Mishin is replaced as head of Soviet space program efforts by Valentin Glushko, who consolidates Soviet space efforts into a new agency, NPO Energia, and promptly cancels the struggling N-1 program

Farewell to the Moon - For Now

Lunar Module Pilot Harrison "Jack" Schmitt loads soil samples

into his lunar rover during Apollo 18, July 17, 1973

1973

Jan 1973:

Soviet Union cancels N-1 rocket program; Paris Peace Treaty ending the Vietnam War signed

Apr 1973:

Launch of Pioneer 11 space probe to Jupiter

July 1973:

Apollo 18 successfully lands at Hyginus Crater, mounting three EVAs using lunar rover and setting new records for lunar exploration, including first scientist astronaut, geologist Harrison Schmitt; evidence found on EVA's of possible lunar lava tubes (Gordon, Brand, Schmitt)

July 1973:

Soviet Mars 4 and Mars 5 probes stage flyby and orbit of Mars

Sep 1973:

Soyuz 12, low earth orbit test of redesigned two-person Soyuz craft (V. Lazarev O. Makarov)

Oct 1973: Yom Kippur War

Dec 1973: Soyuz 13, low earth orbit mission carrying Orion observatory (V. Lebedev, P. Klimuk);

closest approach of much-anticipated Comet Kohoutek disappoints skywatchers around the world

1974

Jan 1974:

Skylab I launches on one of final two Saturn Vs, suffering serious damage to solar panels and micrometeoroid shield/sun shade.

Skylab 2 mounts successful repair and first long duration (28 day) space station mission (Conrad, Weitz, Kerwin)

Mar 1974:

Soviet Mars 6 and Mars 7 landers fail to return usable data

Jun 1974:

Skylab 3 launches for a successful 59 day mission aboard Skylab (Bean, Lousma, Garriott)

July 1974:

Soyuz 14 visits Salyut 3 space station (Yu. Artyukhin, P. Popovich)

Aug 1974:

President Richard M. Nixon resigns from office, and is succeeded by Vice President Gerald R. Ford

Aug 1974:

Soyuz 15 mission fails to dock with Salyut 4 space station (L. Dyomin, G. Sarafanov)

Nov 1974:

Skylab 4 launches for a successful 84 day mission aboard Skylab (Carr, Pogue, Gibson)

Dec 1974:

Soyuz 16 mission tests redesigned Soyuz spacecraft

1975

Jan 1975:

Soyuz 17 mission visits Salyut 4 space station for 29 day mission (G. Grechko, A. Gubarev)

Jan 1975: Defense Department commences Expendable Launch Vehicle Replacement Program to service military launch needs, eventually resulting in selection of Delta 4000

Jan 1975: Valentin Glushko finalizes new Soviet space program, centered around new

Vulkan booster system, a large space modular station,

MOK (later to be named "Mir"), serviced and crewed in turn by Chelomei's

TKS space vehicle

Apr 1975:

Fall of Saigon, South Vietnam to communist forces

Apr 1975:

Soyuz 18 mission fails in docking attempt at Salyut 4 (V. Lazarev, O. Makarov)

July 1975:

Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) I completes first joint U.S.-Soviet manned mission in space, conducting experiments over three days after rendezvous and docking with Soyuz 19 (Stafford, Brand, Slayton, and Leonov, Kubasov); Foundation of National Space Organization, the first major space advocacy organization in the world

1976

Jan 1976: First test launch of AARDV

Jun 1976: Space Station

Salyut 5 launched into orbit by Soviet Union

July 1976:

Skylab 5 launches aboard first Apollo Block III CSM for successful 60 day mission to Skylab, demonstrating successful docking and use of first AARDV as resupply vehicle, and first live interview with press from space as part of American bicentennial celebration (Schweikert, Lind, Lenoir); Viking 1 and 2 successfully land on surface of Mars, returning photographs and sample analysis from Martian surface;

launch of Soyuz 21 mission to Salyut 5 space station (B. Volynov, V. Zholobov)

Aug 1976: Successful deorbit of Skylab over Pacific Ocean, using AARDV engine

Aug 1976: With final launch of Saturn Ib complete, Mobile Launcher Platforms #1 and #3 as well as Launch Pad LC-39B at KSFC commence conversion for the use of the Saturn IC

Oct 1976: Launch of

Soyuz 23 mission to Space Station Salyut 5; mission aborted when Soyuz capsule failed in docking attempts

Nov 1976:

Jimmy Carter is elected President of the United States

1977

??? 1977: NASA announces selection of eighth astronaut group, known as the "Twenty Freaking New Guys," including first women and minority astronaut selections; Congress approves Voyager Uranus program for two follow-up interplanetary probes in the Voyager program, designed to explore the Jupiter and Uranus systems

May 1977:

Debut of George Lucas's "Star Wars"

Jun 1977:

Death of Wernher von Braun

July 1977: First successful test of Saturn IC rocket at Cape Canaveral

Aug 1977: Voyager 2 space probe launched from Cape Canaveral

Sep 1977: Voyager 1 space probe launched from Cape Canaveral; Launch of Soviet

Salyut 6 space station; launch of "Star Trek: The New Voyages" television series on NBC, resurrecting Gene Roddenberry's Star Trek franchise

Nov 1977:

Debut of Steven Spielberg's first contact movie, "Close Encounters of the Third Kind"

A New Era For NASA

First manned launch of NASA's new Saturn IC rocket

from pad LC-39B, Spacelab 2, April 17, 1978

1978

Apr 1978:

Spacelab space station launches into orbit on final Saturn V;

Spacelab 2 crew successfully rendezvouses and docks with station for activation and 28 day mission (Brand, Truly, Musgrave)

July 1978:

Spacelab 3 crew (Young, Cripped, Henize) receives 2 man crew of

Soyuz 29 (N. Rukavishnikov, V. Ryuminas) part of

Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) II for tension-filled international 60 day mission of experiments, successfully receiving AARDV logistics module

Fall 1978: Escalating "Seat Wars" controversy between NASA and ESA is resolved by approval in the FY 1979 NASA budget of Rockwell International proposal for development of a modified

Block III+ Apollo CSM including two additional astronaut seats and a new Mission Module to expand Apollo capability to five man crews

Nov 1978

Spacelab 4 completes extended mission including AARDV logistics flight, and first modular assembly operation in spaceflight history with docking of Airlock Module (Roosa, Fullerton, Thornton)

1979

Jan 1979:

Spacelab 5 arrives for first space station mission overlap, seeing off crew of Spacelab 4, and presence of first ESA astronaut Wubbo Ockels (Engle, Bobko, Ockels); Pioneer Mars launched to Mars

Mar 1979:

Voyager 1, Jupiter Flyby

May 1979:

Spacelab 6 mission (Haise, Overmyer, Allen)

July 1979:

Voyager 2 makes successful flyby of Jupiter

Sep 1979:

Spacelab 7 mission completes record-breaking 120 day mission (Lousma, Hartsfield, Merbold); Mariner Jupiter-Uranus probes launched from Cape Canaveral

Oct 1979: Launch and docking of the European Research Module to Spacelab, the first major ESA contribution to the American program, completed by crew of Spacelab 7; Launch of Voyager 3

Nov 1979: Launch of Voyager 4

Dec 1979:

Soviet Union begins armed military intervention into Afghanistan, escalating Cold War tensions

1980

Jan 1980:

Spacelab 8 mission concludes final flight of the Block III, phased out after this mission in favor of the Block III+ (Weitz, Peterson, Chapman); Launch of first Delta 4000 from Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 40

Jun 1980:

Spacelab 9 mission (Crippen, Hunt, Wood)

July 1980:

Summer Olympics held in Moscow; many Western nations boycott over the invasion of Afghanistan, further eroding detente

Sep 1980:

Spacelab 10 mission successfully employs first flight of Block III+ with 5 persons and with the first French astronaut in space; infamous for the "Garlic Incident';

launch of Carl Sagan's COSMOS program on PBS

Nov 1980: Voyager I flyby of Saturn;

Ronald Reagan is elected President of the United States

1981

Jan 1981:

Spacelab 11 mission includes Peggy Barnes as first US woman in space and first EVA by a Woman in space; NASA and Dept of Defense finally agree to shared development cost of

Saturn Multibody launcher system as a successor to NASA's Saturn IC and the Air Force's Delta 4000; NASA added to EVLRP program as junior partner

Jun 1981:

Spacelab 12 mission: Japanese researcher Katsuyama Hideki was selected to fly in the “short stay” opportunity created by F. Story Musgrave’s double-rotation stay on Spacelab; Voyager 3 flyby of Jupiter

Aug 1981:

Voyager 2, Saturn Flyby

Sep 1981:

Spacelab 13 mission; Voyager 4 flyby of Jupiter

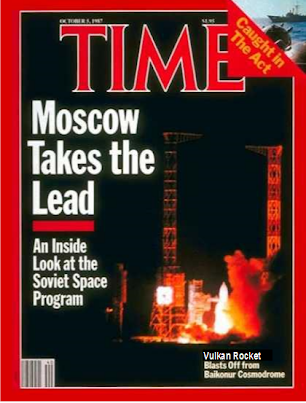

The Cold War Heats Up

"Vulkan Panic" hits American media: Time Magazine, Oct. 8, 1982

1982

Jan 1982: Launch of first Vulkan booster, carrying unmanned TKS spacecraft on a resupply mission to

Salyut 6 - beginning of

"Vulkan Panic" in the West

??? 1982:

Spacelab 14 mission

Mar 1982: Launch of second Vulkan booster, carrying military communications satellite Cosmos 1366 into space

??? 1982:

Spacelab 15 mission

May 1982: President Reagan announces the Strategic Defense Initiative, a national effort to build a comprehensive missile defense shield

July 1982: Responding to Soviet Vulkan launches, President Reagan directs NASA to begin planning a large station to follow up on the successes of Skylab and Spacelab, with possible plans to return to the Moon in the post-1990 timeframe, and announces a large increase in military spaceflight R&D spending, particularly on the Strategic Defense Initiative, resulting in a 20% real increase in funding for FY 1983: Reagan announces that the new U.S. space station will be called "

Freedom"

??? 1982:

Spacelab 16 mission

Nov 1982: Launch of

Salyut 7’s first DOS core module and the first Soviet crew on first manned TKS capsule to the station on third and fourth Vulkan launches, ratcheting up "Vulkan Panic";

death of Leonid Brezhnev, followed by election of Yuri Andropov as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

1983

Feb 1983:

DOS-8 core module launched to complete

Salyut 7 assembly; Soviet Union announces that the name for its new modular space station will be

Mir (Russian for "peace")

??? 1983:

Spacelab 17 mission

??? 1983:

Spacelab 18 mission

??? 1983:

Spacelab 19 mission

Sep 1983:

Shootdown of KAL Flight 007 airliner by Soviet air defense forces

Oct 1983: Debut of movie adaptation of Tom Wolfe's "The Right Stuff", energizing Sen, John Glenn's presidential aspirations;

U.S. invasion of Grenada

Nov 1983:

Able Archer 83 NATO exercise and nuclear crisis

1984

??? 1984:

Spacelab 20 mission: teacher Laura Kinsley becomes the first American non-astronaut to fly in space, visiting Spacelab

Feb 1984:

Death of Yuri Andropov, followed by election of Konstantin Chernenko as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

??? 1984:

Spacelab 21 mission

Apr 1984: Rakesh Sharma becomes first Indian astronaut, visiting

Salyut 7; Final episode of "Star Trek: The New Voyages" is aired on NBC after a successful 154 episode run

July 1984:

Summer Olympics held in Los Angeles; many East Bloc nations refuse to attend in retaliation for 1980 Olympics boycott

Aug 1984: Democratic Presidential nominee Walter Mondale selects Mercury veteran Sen. John Glenn as running mate

??? 1984:

Spacelab 22 mission

Nov 1984: Landslide re-election of Ronald Reagan as President of the United States, defeating Walter Mondale and running mate John Glenn

Dec 1984: Debut of Peter Hyams' "2010: The Year We Make Contact"

1985

??? 1985:

Spacelab 23 mission

Mar 1985:

Election of Mikhail Gorbachev as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

??? 1985:

Spacelab 24 mission

July 1985: Launch of Kirchoff comet probe

??? 1985:

Spacelab 25 mission

??? 1985: Launch of Hubble Space Telescope

1986

Jan 1986:

Voyager 2 makes first-ever flyby of Uranus, discovering 11 new moons and Uranus's tilted magnetic field

??? 1986:

Spacelab 26 mission

Mar 1986: Newton, Suisei/Sakigake, and Gallei cometary probes conduct close encounter with Halley's Comet

Apr 1986:

Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine

??? 1986:

Spacelab 27 mission

Aug 1986: Japan launches first flight of its H-1 rocket, a Delta 4000-derived vehicle with an entirely Japanese-developed Centaur replacement upper stage using a natively-developed LE-5 engine

Sep 1986:

Spacelab 28 mission: Apollo CSM under Cmdr. Don Hunt forced to abort during launch when F1-A engine loses gimble lock; stand-down of Apollo-Spacelab program is immediately announced, pending investigation of accident

Oct 1986:

Reykjavik, Iceland Summit between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev

Nov 1986: Completion of Review Board investigation into launch abort of Spacelab 28 mission

A Last Soviet Hurrah

Spacewalk of Aleksandr Viktorenko during first TKS mission to Mir, April, 1987

(Image: ITAR/TASS TV)

1987

Jan 1987: Launch of Soviet

Space Station Mir's first MOK core module, followed by the first

DOS Lab and

first Soviet Mir crew mission

Feb 1987:

Spacelab 29 mission resumes occupation of Spacelab

Mar 1987: First Saturn Multibody core acceptance-tested; last crew departs Space Station

Salyut 7 in preparation for its deorbit

Apr 1987: The Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) is established by Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Great Britain, and the United States in order to curb the spread of unmanned delivery systems for nuclear weapons, specifically delivery systems that could carry a minimum payload of 500 kg a minimum of 300 km

July 1987: Galileo Probe arrives at Jupiter, releasing probe into Jovian atmosphere., commencing seven year mission to the fifth planet

??? 1987:

Spacelab 30 mission

??? 1987:

Spacelab 31 mission

Nov 1987: Inaugural launch of the Saturn M02, bearing the final Block I AARDV; final testing of functional models of AX-4 and A9 space suits on board Spacelab by astronauts Chris Valente and Peggy Barnes

??? 1987:

DOS-8 'Kvark" Module is added to

Mir as its second intended laboratory module, despite a failure by its Strela-1 robotic crane

Dec 1987:

Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev sign final INF Treaty in Washington, DC, reducing Cold War tensions

1988

Jan 1988:

Spacelab 32 mission: final manned mission to Spacelab, with a three man crew commanded by Don Hunt; deorbit of space station over Indian Ocean follows shortly thereafter using AARDV-14 thrusters; Valentin Glushko begins several months of shuttling between Moscow and Baikonur, trying to secure funding for the continued operations of the Soviet space program

??? 1988: Venus Orbiting Imaging Radar (VOIR) probe is launched to Venus, returning detailed data of Venus's topography and atmosphere

Jun 1988: Voyager 2 completes flyby of Pluto and its moon Charon, heading out into the outer regions of the Solar System

July 1988: Test launch of Saturn H03; Flyby of Kirchoff probe by Comet Tempel-2; Soviets launch Mars 12 and 13 probes to Mars, both dispatching successful landers to Martian surface

Oct 1988: Launch of

Challenger module of U.S.

Space Station Freedom on Saturn H03; First flight of

Apollo Block IV on

Freedom Expedition 1 under Cmdr. Jack Bailey to activate station and complete addition of first truss

Nov 1988:

George H.W. Bush is elected President of the United States

1989

Feb 1989: President George Bush selects Harrison Schmitt, Apollo 18 veteran moonwalker, as new Administrator of NASA;

Soviet Union withdraws from Afghanistan;

DOS-10 Izdelia is added to Soviet Space Station

Mir as its third laboratory module;

Node 1 and

Truss 1 added to U.S. Space Station Freedom

Apr 1989:

Freedom Expedition 2 is launched, completing addition of

Discovery and

Columbus laboratory modules, along with second truss segment, over next few months, to U.S. Space Station Freedom; Death of Valentin Glushko; Vladimir Chelomei is appointed to take his place, and soon begins aggressively pushing his Buran space plane program

May 1989: Maiden flight of Europa 4 booster

July 1989: President Bush and Administrator Schmitt announce a new space initiative,

Project Constellation, announcing a planned return to the Moon; Exploration Report is commenced by the Office of Exploration, outlining a $50 billion plan for a return to the Moon over the next 20 years, with three options considered (A,B,and C) leading up to permanent lunar bases and manned missions to Mars;

Mikhail Gorbachev gives his "Europe as a Common Home" speech in Strasbourg, announcing that the Warsaw Pact nations would be free to decide their own futures

Aug 1989:

Freedom Expedition 3 launched, increasing station crew to 10; U.S. Space Station Freedom officially reaches "Initial Operational Capacity"

Aug 1989:

Voyager makes first-ever flyby of Neptune, discovering its "Great Dark Spot"

Oct 1989:

Freedom Expedition 4 launched

Nov 1989:

Fall of the Berlin Wall and the Revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe

Dec 1989:

Malta Summit between President George Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev recognizes the end of the Cold War

Three Moons In Space

Famous "Triple Moon" photo of space stations Freedom and Mir, Nov. 9, 1989

passing in front of the Moon - the day the Berlin Wall fell

1990

Jan 1990:

Freedom Expedition 5 launched

Feb 1990: Voyager 1 takes the first ever "family portrait" of the Solar System as seen from outside, which includes the famous image known as "Pale Blue Dot"; Soviet space authorities curtail flights to Mir, leaving only a skeleton crew of three cosmonauts to occupy Mir alone for up to eight months at a stretch

Mar 1990: ESA-built Node 2

Harmony added to Space Station Freedom, containing 4 additional CADS ports, and boosters for the station’s life support systems, air and water supplies, and hygiene facilities, as well as the Canadian-built

Cupola;

East Germany holds first free elections

Apr 1990:

Freedom Expedition 6 launched

May 1990: First arrival of a Minotaur cargo vehicle at Space Station Freedom;

East and West Germany sign a treaty agreeing on monetary, economic and social union

??? 1990: Mars Reconnaissance Pioneer probe arrives on Mars

July 1990: Launch of

Freedom Expedition 7, with Alan Shepard, America’s first astronaut and Freedom 7 veteran, sits in as CAPCOM for famous connection with Freedom crew

Aug 1990:

Iraqi invasion and occupation of Kuwait, beginning of Operation Desert Shield

Late 1990: Approval by Congress of

Project Constellation of NASA's Exploration Report's "Option A," limited to lunar sorties and studies of eventual lunar bases; Administrator Schmitt creates two new offices,

Artemis for the planned lunar return program, and

Ares for reviewing existing and developing technologies with an eye towards Mars exploration

Fall 1990: Robert Zubrin mounts vigorous but unsuccessful campaign to replace Exploration Report lunar-focused recommendations with a Mars First program;

Bank of Japan slashes interest rates, leading to the long Japanese recession, "the Lost Decade," of the 1990's; Soviet authorities order remaining military satellite launches on the Soyuz rocket transferred to the more secure Plesetsk launch site in northern Russia

Oct 1990:

Freedom Expedition 8 launched;

Germany officially reunifies, and begins the long and costly task of rejuvenating the Eastern German economy

Nov 1990:

Centrifuge Gravity Lab Module, a unit to test the effects of simulated gravity, is added to Space Station Freedom, and quickly becomes known as "McDonald's Farm"

1991

Jan 1991:

Freedom Expedition 9 launched

Feb 1991:

Iraq defeated in four day Persian Gulf War

Apr 1991:

Freedom Expedition 10 launched

Jun 1991: Japanese

Kibo Module attached to Space Station Freedom, now served by a constant rotation of Japanese crewmembers flying to the station on American Apollo capsules; the attachment of

Kibo completes the assembly of Space Station Freedom

July 1991: Disastrous fire at Baikonur cosmodrome destroys Site 1, including the famous Gagarin's Start launch pad, providing another ominous sign of Soviet collapse;

Freedom Expedition 11 launched

Aug 1991:

Attempted hardline coup in Soviet Union; Soviet republics rapidly announce their independence from the USSR

Oct 1991:

Freedom Expedition 12 launched

Dec 1991:

Dissolution of the Soviet Union; resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev as Soviet leader on Christmas Day

1992

Jan 1992:

Freedom Expedition 13 launched

??? 1992: Launch of Near Earth Asteroid Pioneer probe

??? 1992: Mars Traverse Rovers (Liberty, Independence) arrive on Mars

??? 1992: India reaches agreement with Russia to develop a new clustered-core booster and hosting of sveral Indian astronauts on spapce station Mir

Apr 1992:

Freedom Expedition 14 launched

July 1992:

Freedom Expedition 15 launched

Oct 1992:

Freedom Expedition 16 launched

Nov 1992:

Election of Bill Clinton as President of the United States

Late 1992: China reaches agreement with Roscosmos, the new Russian space agency, and Energia on a proposal to offer support for Chinese development of rockets and capsules and Chinese completion and crewing of final DOS module to space station Mir

1993

Feb 1993: Launch of Piazzi asteroid probe

??? 1993: Robert Zubrin announces the creation of a new organization, On To Mars, with the sole goal of promoting a Mars mission as the next logical step for the American space program

1994

May 1994: Galileo space probe observes spectacular impact of elements of comet Galileo on Jupiter, reprogrammed to reenter Jovian atmosphere shortly thereafter

1995

Jan 1995: Hubble Space Telescope finally reenters Earth atmosphere after nearly ten years of enormously fruitful service in orbit

??? 1995: Vladimir Chelomei forced to retire from NPO Mashinostroyenia in 1995