Welcome to the thread, the goal here is to try and outline the real history of pre colonial Australia and to discuss potential avenues for alternative history and the challenges there-in. Before we begin in earnest I would like to note I have read the Lands of Red & gold and enjoyed it, but that its understanding of Pre Colonial Australia and First Nations cultures is rather outdated, which is probably the best place to start, IE, what is know about Pre Colonial Australia? (My main sources for this are Dark Emu, the Biggest Estate on Earth and William, Alan (24 April 2013). "A new population curve for prehistoric Australia". Proceedings of the Royal Society.)

A common recurring element I see when this topic comes up is that Australia was too environmentally desert-ous and lacking in both beasts of burdens and domesticable crops for much to easily change. This stance lines up with older historical records and revisions, but isn't actually reflective of the current archeological, or historical understanding of the continent anymore. I obviously cannot transcribe the entire books, though I can link a useful YouTube video that covers some additional points, but I can provide a rundown of some major points:

Some examples include:

This of course doesn't mean one can't do alt histories, or not create radically different cultures and societies, it simply means the process involves different challenges than in other locales or times. Australia has a rich and extremely long history and while the land is incredibly hard to work, there are plenty of alternative paths one can create with some creativity and a lot of luck.

A common recurring element I see when this topic comes up is that Australia was too environmentally desert-ous and lacking in both beasts of burdens and domesticable crops for much to easily change. This stance lines up with older historical records and revisions, but isn't actually reflective of the current archeological, or historical understanding of the continent anymore. I obviously cannot transcribe the entire books, though I can link a useful YouTube video that covers some additional points, but I can provide a rundown of some major points:

- There's little to no archeological evidence of large-scale warfare which influenced tool design and was likely informed by the need to large-scale cooperation to effectively manage the land.

- Colonial explorers often compared Australia's environment to that of an expansive park, but claimed it was natures clumsy hand when in fact it was land management on an epic scale designed to create vast herding grounds and forests, which also protected crop growing spaces and settlements from wild animal incursions and made them easy to manage.

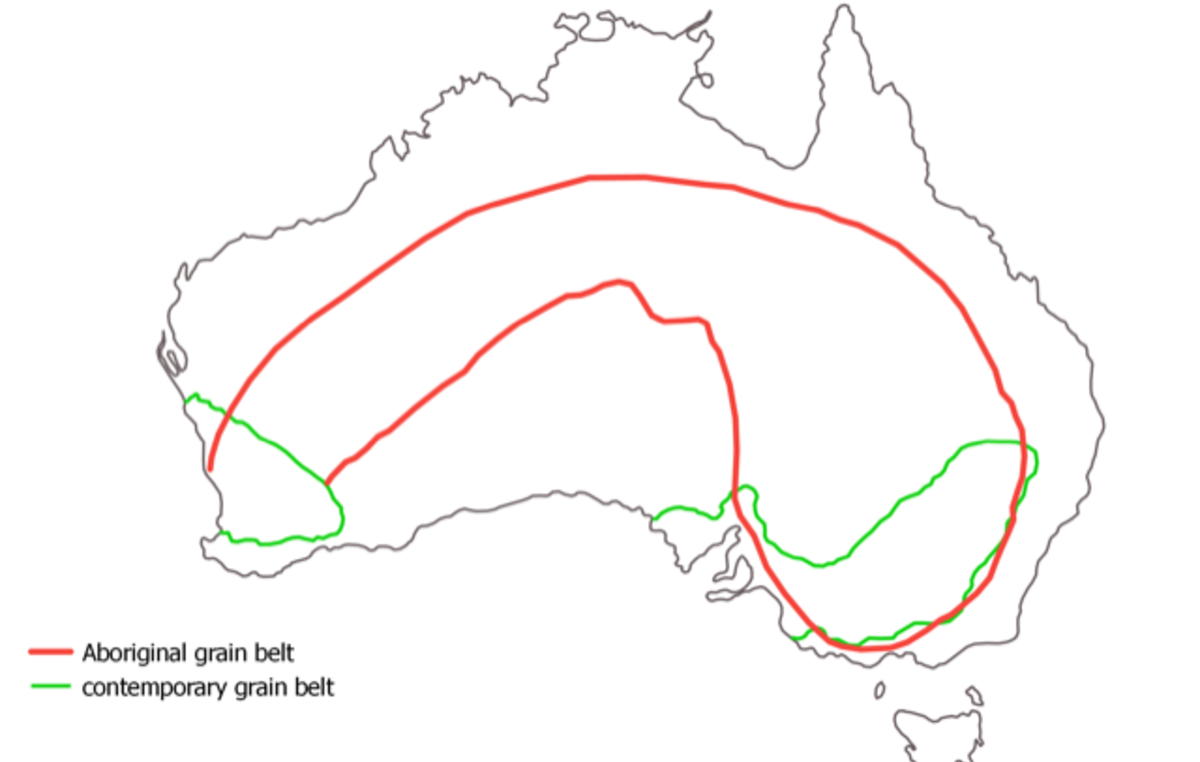

- The different language groups were not isolationist or cut off from one another, records show of items from the Far East making their way through trade networks far into the middle country and the wheatbelt took up more than half the country and stretched from the far South East being grown in the North West. We know that the 'Message Stick' was a widely respected tool for communication across the lands. There is confirmed records of Macassan contact with Australia, as well as evidence of the Sama-Bajau and & the Kilwa Sultanate engaging in trade with the First Nation, along with Javanese contact with Australia which references their sailors going passed Tasmania!. Plus possibly a Chinese settlement given the Chinese statue of Shou Lao, the Chinese god of longevity dug up in 1879 near Darwin, its theorized this one is tied to the expeditions of Cheng Ho. (This article discusses it more, though I am unsure on some of its reliability.)

- We know that stone houses and monolithic stone structures akin to those seen across the world were present but the former were destroyed by invaders and the latter were usually destroyed and or attributed to some mysteriously missing white people. There were also various types of automated fishing structures such as fish traps in rivers that are over 8000 years old at least and exist at different levels that work like a maze to trap fish; as well as larger structures that funneled water & fish into basins for catch and use.

- Large-scale cooperation across national and language lines was seen when it came to orchestrating burning offs of forests to prevent forest fires, manage the herds and improve the soil. there was also much coordination in the construction of large kennels to herd thousands of kangaroos into for culling to control the population, as well as many other such events.

- Indigenous communities actually had several examples of domesticated crops, not just the nuts, but also vast fields of wheat that were formed into bails that stretched on further than the eye could see and was used to make an extremely soft and fluffy flower for cakes. They also had yam farms and several fruit crops, the latter of which were turned into an edible paste and more, with many of these being extremely ancient practices. They also discovered a way to engage in long term food storage for some of these products and overall produced a surplus which would be stored, traded or gifted; they also had rows and rows of massive enclosed cooking stoves.

- The current estimates for the overall population pre the introduction of foreign diseases or invasion is 1.2 million. Most structures and settlements however were designed with the purpose of not damaging or disrupting the land long term, or designed to just be temporary for the more nomadically inclined, which lessened their archeological footprint.

- Attached here is a good radio interview discussing how horrible of Australia's native wildlife are for sedentary domestication. But in the short term, they dig, they run, they rarely have a hierarchal structure, they can be very violent and they don't breed super efficiently and are incredibly hard to pen even by modern standards.

Some examples include:

- Vast tracks of grassland that seemed ideal for grazing being completely unable to handle cloven hooved animals, which compacted them down so much the land became bone dry.

- Indigenous communities warning colonizers to do burn offs but being chased away, leading to massive forest fires within a year along with the animals and invasive weeds quickly growing out of control.

- This one isn't directly from the books, but its been observed that detrimental environmental changes have caused many great lakes to become salt lakes and there isn't a convenient way to fix that once it happens.

- Knock on effects from these and other factors caused mass die offs at incredibly quick rates, leading to advancing deserts and large-scale ecological collapse; factors like these and overcoming these challenges can be reasoned to inform a great deal about the First Nations cultures and practices.

This of course doesn't mean one can't do alt histories, or not create radically different cultures and societies, it simply means the process involves different challenges than in other locales or times. Australia has a rich and extremely long history and while the land is incredibly hard to work, there are plenty of alternative paths one can create with some creativity and a lot of luck.

Last edited: