@Miss Construction, in her alt-20th century TL, has talked about domestication of Grevy’s Zebra. In @Salvador79’s thread on alt-Neolithic/Bronze Age SE Europe, Equid domestication came up and it was stated (by @Salvador79 himself?), that horse genetics show that mares were widely domesticated, but very few stallions ever were (in the thread this was used to butterfly away horse domestication by PIE steppe dwellers). Given the behaviour of stallions in wild Equids, this seems very plausible - a captured wild-reared stallion would probably be impossible to tame. I suggested that it was likely that any progenitor stallions for domestic horses were probably hand-reared, and likely to be offspring of captured pregnant mares, and that even then it would probably need a hand-reared stallion with an unusually docile temperament to pass on genes allowing full domestication. I wonder to what extent this is true, and how it might relate to the perceived difficulty of Zebra domestication?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Cool Potential Domestications

- Thread starter DG Valdron

- Start date

I'm no expert on Zebras, but I imagine the way Zebras are like today owes to the absence, historically, of great necessity to domesticate them. But I'm not sure of course.

You don't necessarily always need captive stallions for breeding purposes. Many early domestications took in a great deal of stock, inadvertently and intentionally, from wild males (and females added to the herd). It might seem counter-intuitive to 'domestication' at first but is a great step to keeping numbers up and getting the ball rolling to more directed breeding. A notably unruly stallion can easily be turned into a more manageable gelding, but in general having a slightly temperamental male wouldn't be a big problem, especially if you're using him to guard the herd. I do agree that bringing in wild adult males as a permanent addition to the herd probably isn't going to happen.@Miss Construction, in her alt-20th century TL, has talked about domestication of Grevy’s Zebra. In @Salvador79’s thread on alt-Neolithic/Bronze Age SE Europe, Equid domestication came up and it was stated (by @Salvador79 himself?), that horse genetics show that mares were widely domesticated, but very few stallions ever were (in the thread this was used to butterfly away horse domestication by PIE steppe dwellers). Given the behaviour of stallions in wild Equids, this seems very plausible - a captured wild-reared stallion would probably be impossible to tame. I suggested that it was likely that any progenitor stallions for domestic horses were probably hand-reared, and likely to be offspring of captured pregnant mares, and that even then it would probably need a hand-reared stallion with an unusually docile temperament to pass on genes allowing full domestication. I wonder to what extent this is true, and how it might relate to the perceived difficulty of Zebra domestication?

Zebra domestication was perceived as 'difficult' because the people saying so were already used to domestic horses that already had the 'kinks' sorted out, plus they didn't have as big a grasp on the difference between domesticating and taming something. Despite the complaints in these early accounts, taming a zebra is quite far from an impossible task -- they just take a little more TLC and perhaps a slightly different approach than a domestic animal.

In any case, nobody's going to jump straight to riding and driving during domestication. Even the first horses were probably meat animals, and at best pack animals.

That's actually essentially how nearly every animal got domesticated in ancient times, in a manner of speaking. No animal is a domestication magnet; nothing ever automatically finds its way into human life just because it's a 'perfect candidate'. Not even dogs and cats. If this were true we'd find evidence of independent domestication events in nearly every area where humans and that species overlap, which would be absurd.I'm no expert on Zebras, but I imagine the way Zebras are like today owes to the absence, historically, of great necessity to domesticate them. But I'm not sure of course.

Whether or not a population of animals winds up in a close, positive association with humans is perhaps partly up to environmental conditions, but ultimately up to the culture; the technicalities of their lifestyle as well as choice, influenced by their philosophies. The people that shared land with zebras weren't in a physical position to tame them, didn't have much of a need to do so and the concept probably was alien or contrary to their worldviews. In another time maybe some group of people would have developed a closer relationship to zebras in some way, and that leading to more intensive management, but they'd need a reason, whatever it is, to be doing all of this.

Domestication of these animals would have been really interesting:

Tapir. I'd love to see tapirs as very common animals in farms and even free-roaming in cities across the world like sika deer in one of Japanese cities.

Asian elephant. I know they're semi-domesticated, but they could have been fully-domesticated if people had domesticated them much earlier and removed musth in all elephants, making them much more peaceful.

Some species of ground sloth. They would be useful in having bony armor that could be made for armor to protect people.

Chalicotherium. Imagine seeing these being farmed for their clawed fingers and for milk and meat production.

Ancylotherium. Chalicotherium's close relative and another cool candidate for domestication, probably could be used for meat and milking production.

Diprotodon. If they were not even aggressive and were tame enough, they could have been domesticated by early people for their meat and milk as alternatives for cattle.

Tapir. I'd love to see tapirs as very common animals in farms and even free-roaming in cities across the world like sika deer in one of Japanese cities.

Asian elephant. I know they're semi-domesticated, but they could have been fully-domesticated if people had domesticated them much earlier and removed musth in all elephants, making them much more peaceful.

Some species of ground sloth. They would be useful in having bony armor that could be made for armor to protect people.

Chalicotherium. Imagine seeing these being farmed for their clawed fingers and for milk and meat production.

Ancylotherium. Chalicotherium's close relative and another cool candidate for domestication, probably could be used for meat and milking production.

Diprotodon. If they were not even aggressive and were tame enough, they could have been domesticated by early people for their meat and milk as alternatives for cattle.

Last edited:

mojojojo

Gone Fishin'

S.M.Stirling's LOC series had riding animals on Venus that were the descendants of transplanted Chalicotherium. They were described as "Horse sized dogs with a pig's digestive track"Domestication of these animals would have been really interesting:

Chalicotherium. Imagine seeing these being farmed for their clawed fingers and for milk and meat production.

.

Everyone who plays ARK knows you can easily tame them with beer!S.M.Stirling's LOC series had riding animals on Venus that were the descendants of transplanted Chalicotherium. They were described as "Horse sized dogs with a pig's digestive track"

However they were extinct long H.sapiens showed up.Chalicotherium. Imagine seeing these being farmed for their clawed fingers and for milk and meat production.

This is a giant wombat, right? Milking marsupials would be a challenging task, one that I severely doubt would happen.Diprotodon. If they were not even aggressive and were tame enough, they could have been domesticated by early people for their meat and milk as alternatives for cattle.

However they were extinct long H.sapiens showed up.

I understand that, I'm just saying if Chalicotherium did managed to survive in the longer run, humans could have domesticated them.

This is a giant wombat, right? Milking marsupials would be a challenging task, one that I severely doubt would happen.

Maybe humans would manage to do this complicated task over time and would successfully milk Diprotodons. I also understand that Diprotodon is a giant wombat.

Last edited:

Did you mean to say 'could'?I understand that, I'm just saying if Chalicotherium did managed to survive in the longer run, humans would have domesticated them.

Either way there's plenty of variables we don't know about them.

This is a giant wombat, right? Milking marsupials would be a challenging task, one that I severely doubt would happen.

Still, in the other hand, you could milk them in all seasons, rain or snow, and never get cold fingers. For me that would be worth something.

John Mortimer

Banned

How about the world's largest rodent? The Capybara.

They're social animals living in groups of 100. Some people even have them as pets.

Casteroides is another option. Not sure what would be the function of a 270lb beaver though. They didn't eat wood. They were predators. Maybe they could have been some sort of hunting companion, or a shepherd.

They're social animals living in groups of 100. Some people even have them as pets.

Casteroides is another option. Not sure what would be the function of a 270lb beaver though. They didn't eat wood. They were predators. Maybe they could have been some sort of hunting companion, or a shepherd.

Last edited:

Found this tumblr post on the domestication effect and figured it might be relevant/useful for this thread.

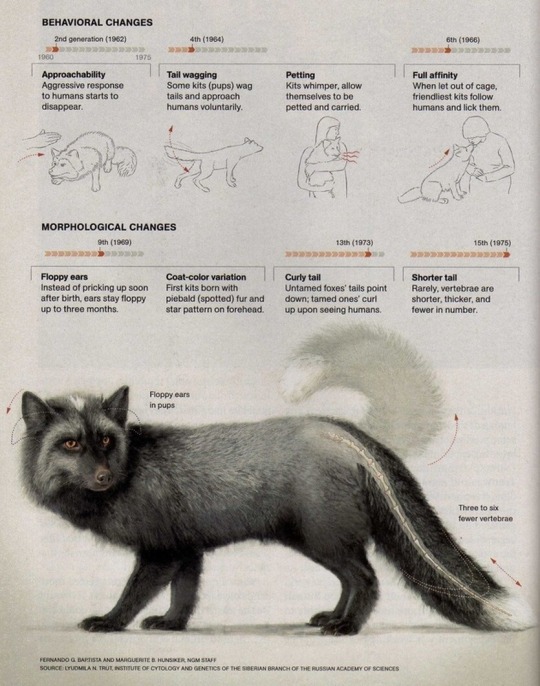

curlicuecal@tumblr.com said:Basically scientists have found that if you start selecting for people-friendly animals, you see a bunch of hypothetically unrelated traits start showing up in all sorts of mammal species: floppy ears, piebald/patterned coats, etc.

This is true for everything from cows to dogs to rats! One of the coolest long term studies on this has been the Russian fox experiments.

So essentially the science goes like this:

You have two copies of every genes, one from each parent.

We tend to simplify genetics, and say that for every single gene you have it is random,l coin flip which copy you pass on to you offspring. We also tend think of genes as a 1:1 ratio of genes—>traits.

But! This is not quite the case.

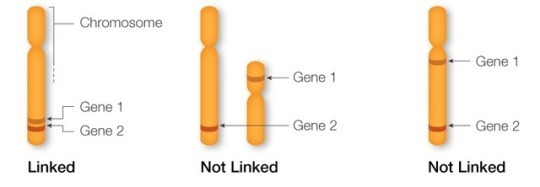

Genes have a specific physical location and order relative to each other on your chromosomes, and the chance of genes being inherited together goes up the closer together they are located. This means random, unrelated traits can wind up being more commonly inherited together in specific patterns just because those genes are located close together, and you don’t get that completely random reshuffling of two parent’s traits. Some of them tend to stay “stuck” together.

This is called linkage, and it’s why you often see red hair, pale skin, and freckles together, for example.

The second factor that plays into this is that a lot of times 1 gene affects several different traits (or several different genes affect 1 trait). This means that sometimes you really *can’t* untangle two traits because they have a similar cause. For example, say genes for increased aggression are responsible both for making a spider a better hunter (pro) and making a spider more likely to eat its offspring (con). Because the same gene is the cause of both things, natural selection can’t really untangle them.

Circling back to the redhead/freckles/pale skin example, these traits are affected by a number of different genes, but also one gene in particular: MCR1, a gene that changes how your body responds to hormones promoting melanin production. Again, one gene related to pigment production can affect a BUNCH of different traits. (And also skin cancer risk. Fun!)

Domestication Syndrome in mammals turns out to be due to both linkage and genes affect by multiple traits!

See, when we domestic animals we want them to be friendlier/less aggressive, which normally translates to less FEARFUL.

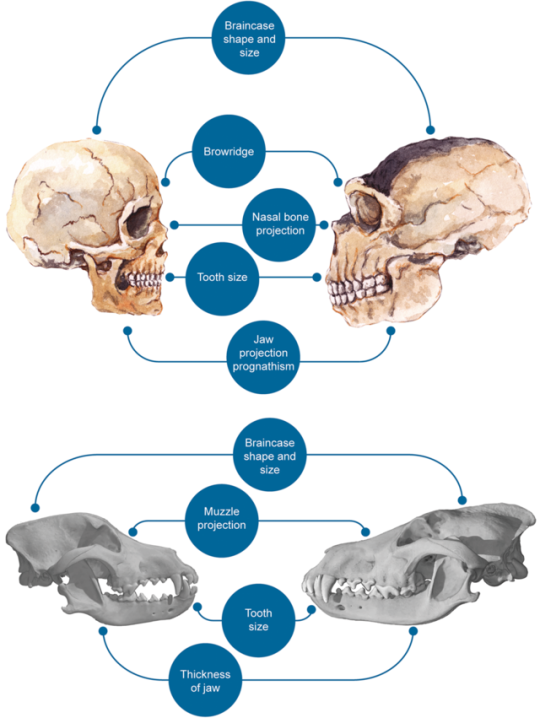

And it turns out that the same genes involved in adrenal responses and other stress reactions are also involved in melanin, cartilage, and bone production. So when we domesticate animals we get these recurring changes in pigmentation (white patches, piebald costs), floppy ears (cartilage), shorter muzzles and other changes in physical stature (bone growth), etc.

We also wind up selecting for a lot of neotenic genes in general— that is, retention of childhood traits into adulthood. That’s because baby animals tend to have lots of friendly/trusting/biddable/curious traits we are looking for.

And honestly, who can say no to a face like this?

ps, since it was mentioned:

the same genes involved in domestication probably help animals form social groups in general. if you need to get along with and trust strangers you need a decrease in the panic/aggression genes.

cats, for example, probably domesticated themselves when they started living close to each other and to humans to feed off of pests in grain silos.

and yeah, some some recent theories suggest humans may have ‘domesticated’ themselves:

sainatsukino@tumblr.com said:so basically you’re saying that when we breed animals to be friends, they become friend-shaped.

Driftless

Donor

Found this tumblr post on the domestication effect and figured it might be relevant/useful for this thread.

.sainatsukino@tumblr.com said:

so basically you’re saying that when we breed animals to be friends, they become friend-shaped

Not too far of a reach from the idea that "we create God in man's image".... And make that fit domesticated animals as you choose...

The problem with Asian elephants is that they live a long time, and have a really slow, 20 to 25 year maturation process. So you need one of two things to domesticate Asian elephants:

1) A really fast-breeding subspecies of Asian elephants that can reach maturity inside of four or five years.

2) An isolated population with no better alternatives that is stable enough to want to invest in a domesticate with a 25 year life cycle.

As for Tapirs, I seem to recall looking into them. As I recall, one of the issues was finicky diets. But possibly, with the right culture, it might maybe have happened.

1) A really fast-breeding subspecies of Asian elephants that can reach maturity inside of four or five years.

2) An isolated population with no better alternatives that is stable enough to want to invest in a domesticate with a 25 year life cycle.

As for Tapirs, I seem to recall looking into them. As I recall, one of the issues was finicky diets. But possibly, with the right culture, it might maybe have happened.

While I'm not contesting a potential link between aggression and fur colors, I think piebaldism is incidental to domestication and not necessarily directly linked to docility. There's plenty of animals that don't express that phenotype but are still perfectly approachable. Maybe the neural crest mutation (which is what the tumblr post is talking about) leads to a more available radiation of fur patterns, but even without it a few phenotypes would still be available for selection. People who breed exotics like reptiles and invertebrates have managed to create morphs with striking color variation, but it doesn't seem to be linked with docility.Found this tumblr post on the domestication effect and figured it might be relevant/useful for this thread.

Piebaldism, melanism and leucism are all incredibly common (mostly) recessive mutations, and all occur in the wild at least some point in time for most species. However, they're usually never advantageous and are selected against so they don't show up. When humans are involved, sticking out doesn't matter, in fact being uniquely colored like that might be positive. So that's selected for along with other factors like aggression.

But I'm much more inclined to believe the connection between cartilage (lop-ear) and docility. Every lop-eared animal I've seen appears to be much more calm and laid-back than animals with wildtype ears. I've seen plenty of articles linking the neural crest to the ears, and also to sociability - humans have a similar neural crest mutation called Williams' Syndrome which basically gives you big ears and makes you hyper-friendly. So there's definitely something to that.

Also very slow reproduction rate and growth period.As for Tapirs, I seem to recall looking into them. As I recall, one of the issues was finicky diets. But possibly, with the right culture, it might maybe have happened.

Replacing cattle? Displacing bison? Or supplementing?mamoth farms from Novosibirsk to Newfoundland.

As a supplement to cattle/bison for North America: ostriches. Or, if we can reach back a bit farther, elephant birds.

Re-engineered dwarf Cretan mammoths might be able to actually replace cattle assuming their small size entails a brief gestation period. But a massive part of any mammoth agriculture is going to be, at least in the beginning, tourism.Replacing cattle? Displacing bison? Or supplementing?

Would the dwarf elephants in Borneo and Sumatra work, they are smaller thus requiring less food but is their gestation period the same as regular sized elephants?

P.S has anyone suggested Platypuses, I think with their milk and egg production as well as lack of direct competition with humans over food, they could make excellent domesticates

P.S has anyone suggested Platypuses, I think with their milk and egg production as well as lack of direct competition with humans over food, they could make excellent domesticates

Share: