1ST BATTLE OF MIDWAY -: 17-21 June 1942

Prologue

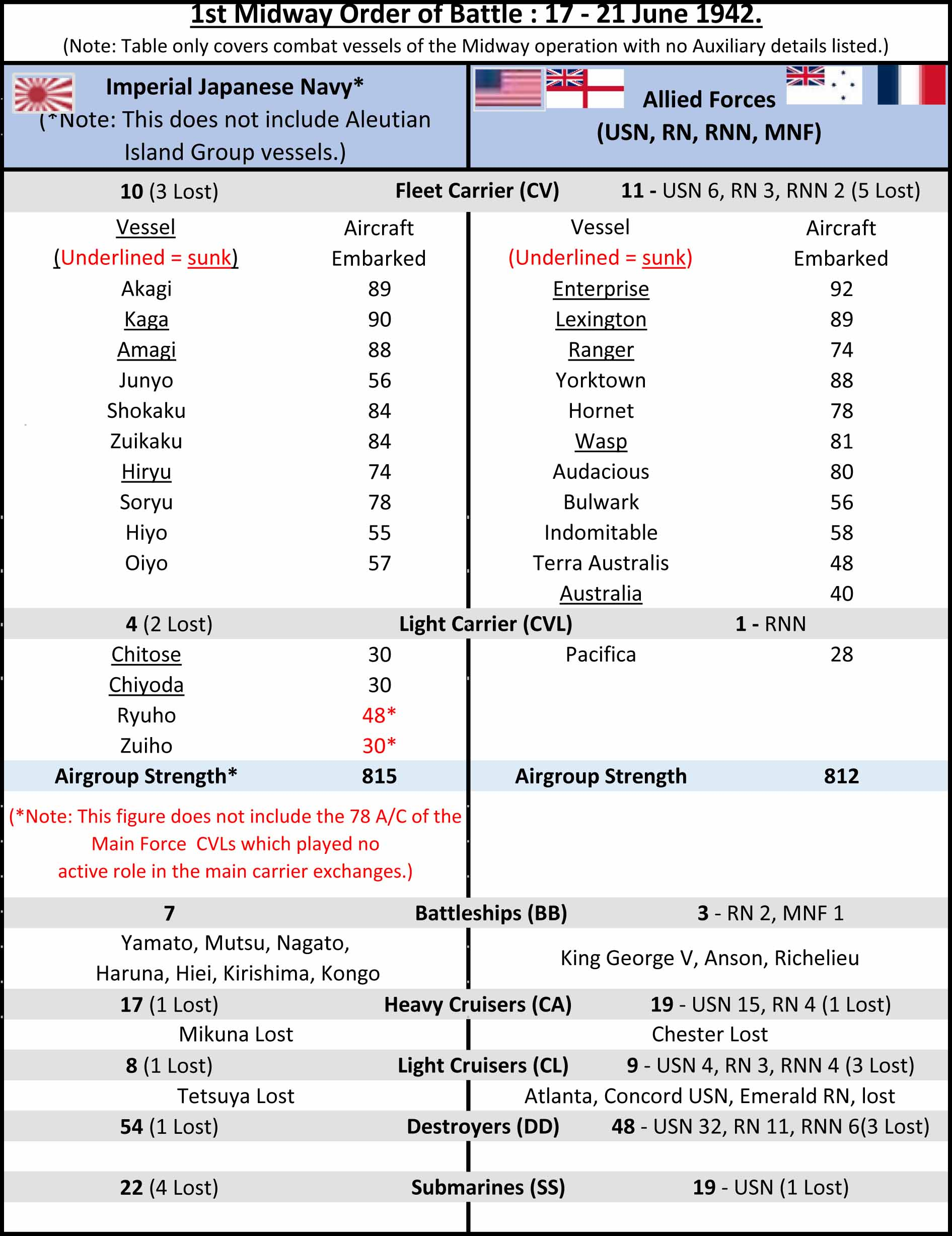

Greetings all. I originally started to post this on the "Create the Largest Naval Battle you can sometime after the start of WW1" thread, but then had second thoughts and decided to post it as a new thread, hopefully to generate a lot of Battle specific response. It would have fitted the first thread fine due to the large change in force levels involved, but being such a pivotal battle it always seems to generate its own momentum and responses. Look closely and you will see that this includes 26, yes 26 aircraft carriers! Before you collectively blow a raspberry and assume that I've plucked these figures out of my #rs@, the scenario is an amalgam of concepts and force structure from four other timelines to form a logical progression in achieving this, and for AH purposes, plausible AU. I'll do my best to put how we arrived at this force level and show these in context to establish how I arrived at this battle, and hopefully you can look at this and the referenced TL to get a less knee-jerk initial reaction. Trust me I hope you will find it enjoyable and basically interesting exercise to change perspective on a classic conflict when I get it done. Regardless the pleasure is mine in seeing other responses to the scenarios I present, and I look forward to and value your feedback. Tangles.

To put this in context and the shape and structure of the forces involved I'll present other AU TL that shaped the context of this offering and brief synopsis of why they are relevant.

Firstly, there are the works of David Rowe, in particular his Book 3 title 'Holding the line" of the 'Whale has Wings' Series. This is the basis of the inclusion of Allied TF58 into the 'Mare Americanus' of the Pacific Campaign. The combined Allied BB/CV force structure presented and its involvement in Midway is a direct crib of that AU. In his narrative the Atlantic Campaign has developed in the favor of the UK, so that Britain has been able to shake free large force elements for involvement against Japan, changing the shape of the DEI battle and retaining Singapore. His scenario directly sees 3xBB, and 3CV supporting the USN ops in Midway, though with a different Battle structure. Note the reduced threat in the Atlantic means that the USN have the option to free the Wasp and Ranger to be available for employment in the Pacific to face the increased Japanese threat. This is basis for inclusion of these additional elements of the larger force structure.

Secondly, A Moscow Option by David Downing shapes the concept of battle, were the IJN becomes aware that the USN is reading their signals and Yamamoto reshapes the concept of the Midway operation to take advantage of this. The operational changes involved in this result in the changed date of battle, with the deferment resulting in Halsey's medical release and involvement in the conduct of the battle as to be detailed. I could elaborate more here on the importance of this but will save that for presentation of the actual battle thread soon.

Thirdly is the work of John Hardinge and his works on an AU where Australia and NZ are a single Dominion State of Britain and its impacts, which form a basis for my own TL.

This lastly leads to my own Nieustralis AU of which this will be a component chapter. How this shapes the force structure arises from changes to the WNT post WW1, where the BB provisions are detailed with more vigor, but less so for the carriers. Arising from this historic change both the USN and IJN can retain four not two hulls of their existing capital ship hulls under construction. The result is that both forces are starting the Pacific campaign from a higher base line naval aviation force, the USN with four Saratoga's, with the addition of Constellation and Independance, while the IJN have the Tosa and Amagi ITTL. Subsequently for the IJN the Junyo class is actually three vessels with the third vessel Oiyo added ITTL. Also, the WNT Carrier changes mean that both Ranger and Wasp are completed as a single class prior to the Yorktown's, but with the same historic weakness implicit in their original designs. This change also means that the USN will eventually construct five Yorktown class carriers ITTL, thought the last two, Ticonderoga and Bonhomme Richard, are still nearing completion and commissioning ITTL as the battle commences. From these historic alterations there are several knock-on effects. Again, drawing on David Row's work, the British raid on Taranto is a multiple carrier operation, resulting in the extension of the target list to include the tank farms and submarine base, with assistance of RAF Wellingtons from Malta. As IRL the IJN closely studies the British operation leading to their changing the Pearl Harbor attack to reflect this. Also, the impact of an eight carrier Kido Butai for the Pearl Harbor raid is vital. Avoiding the old 'third strike at PH saw" with the additional carrier strength the attack still has only the historic two waves involved. But both as a result of the changes are far stronger, and with the example of the British ITTL, target base facilities resulting in far more infrastructure damage, loss of the fuel storage and Submarine base for example. This has introduced logistical and support issues for the USN leading up to the 1st Midway I am presenting.

The second flow on ITTL regards the Nieustralis navy (RNN). Here the dominion is a separate observer for WNT purposes, with its two BCs ITTL demilitarized and not scrapped as occurred IRL. Post war as a result, it goes down the naval aviation development line in conjunction to the theme developed by David Rowes AU. By getting two Hawkins class carrier conversions as CVLs instead of the acquiring the two County class CAs as occurred IOTL. With the invasion of Manchuria in 1932 they convert their BCs to small CVs (think HMS Furious analog), and after 1937 IOT replace the Hawkins approach Britain for the T-class CV (think something between the Colossus and Illustrious, HMS Indomitable lite, single hanger, much lighter side armor etc.). This means that with the reduced tempo of the Atlantic they agitate to move greater forces to the Pacific campaign. IRL this applied to the infantry forces deployed in the Western Desert, but it is realistic to extend this premise to the RNN carriers ITTL. This will result in a number of smaller carriers also in the Pacific theatre and it will play its part in the scenario developing.

The net result of these changes will lead to a longer and more attritional Pacific campaign in this AU, and this will represent the first of four major carrier battles in the Pacific, and by far the largest naval battle of WW2 to date. First Midway will represent the first and as can be seen by the table tendered, far the largest carrier battle of World War Two to date, where the size and power of the naval aviation represents a major change in the conduct of naval warfare.

This is the logical basis for the evolution of the seemingly outrageous force levels involved in this battle concept. But I hope you will see that there is a progression behind the events leading to the battle detailed. If you are interested, please look at the relevant stories mentioned as a basis, and this can help frame further critique when I get back and present my offering. I hope this preamble isn't too long winded and has whet your appetite for what is to come. There might be some initial delay as I'm going to be coming off a surgical procedure shortly, but still wanted to start this to have something to distract me whan I get back.

Regards T.

Prologue

Greetings all. I originally started to post this on the "Create the Largest Naval Battle you can sometime after the start of WW1" thread, but then had second thoughts and decided to post it as a new thread, hopefully to generate a lot of Battle specific response. It would have fitted the first thread fine due to the large change in force levels involved, but being such a pivotal battle it always seems to generate its own momentum and responses. Look closely and you will see that this includes 26, yes 26 aircraft carriers! Before you collectively blow a raspberry and assume that I've plucked these figures out of my #rs@, the scenario is an amalgam of concepts and force structure from four other timelines to form a logical progression in achieving this, and for AH purposes, plausible AU. I'll do my best to put how we arrived at this force level and show these in context to establish how I arrived at this battle, and hopefully you can look at this and the referenced TL to get a less knee-jerk initial reaction. Trust me I hope you will find it enjoyable and basically interesting exercise to change perspective on a classic conflict when I get it done. Regardless the pleasure is mine in seeing other responses to the scenarios I present, and I look forward to and value your feedback. Tangles.

To put this in context and the shape and structure of the forces involved I'll present other AU TL that shaped the context of this offering and brief synopsis of why they are relevant.

Firstly, there are the works of David Rowe, in particular his Book 3 title 'Holding the line" of the 'Whale has Wings' Series. This is the basis of the inclusion of Allied TF58 into the 'Mare Americanus' of the Pacific Campaign. The combined Allied BB/CV force structure presented and its involvement in Midway is a direct crib of that AU. In his narrative the Atlantic Campaign has developed in the favor of the UK, so that Britain has been able to shake free large force elements for involvement against Japan, changing the shape of the DEI battle and retaining Singapore. His scenario directly sees 3xBB, and 3CV supporting the USN ops in Midway, though with a different Battle structure. Note the reduced threat in the Atlantic means that the USN have the option to free the Wasp and Ranger to be available for employment in the Pacific to face the increased Japanese threat. This is basis for inclusion of these additional elements of the larger force structure.

Secondly, A Moscow Option by David Downing shapes the concept of battle, were the IJN becomes aware that the USN is reading their signals and Yamamoto reshapes the concept of the Midway operation to take advantage of this. The operational changes involved in this result in the changed date of battle, with the deferment resulting in Halsey's medical release and involvement in the conduct of the battle as to be detailed. I could elaborate more here on the importance of this but will save that for presentation of the actual battle thread soon.

Thirdly is the work of John Hardinge and his works on an AU where Australia and NZ are a single Dominion State of Britain and its impacts, which form a basis for my own TL.

This lastly leads to my own Nieustralis AU of which this will be a component chapter. How this shapes the force structure arises from changes to the WNT post WW1, where the BB provisions are detailed with more vigor, but less so for the carriers. Arising from this historic change both the USN and IJN can retain four not two hulls of their existing capital ship hulls under construction. The result is that both forces are starting the Pacific campaign from a higher base line naval aviation force, the USN with four Saratoga's, with the addition of Constellation and Independance, while the IJN have the Tosa and Amagi ITTL. Subsequently for the IJN the Junyo class is actually three vessels with the third vessel Oiyo added ITTL. Also, the WNT Carrier changes mean that both Ranger and Wasp are completed as a single class prior to the Yorktown's, but with the same historic weakness implicit in their original designs. This change also means that the USN will eventually construct five Yorktown class carriers ITTL, thought the last two, Ticonderoga and Bonhomme Richard, are still nearing completion and commissioning ITTL as the battle commences. From these historic alterations there are several knock-on effects. Again, drawing on David Row's work, the British raid on Taranto is a multiple carrier operation, resulting in the extension of the target list to include the tank farms and submarine base, with assistance of RAF Wellingtons from Malta. As IRL the IJN closely studies the British operation leading to their changing the Pearl Harbor attack to reflect this. Also, the impact of an eight carrier Kido Butai for the Pearl Harbor raid is vital. Avoiding the old 'third strike at PH saw" with the additional carrier strength the attack still has only the historic two waves involved. But both as a result of the changes are far stronger, and with the example of the British ITTL, target base facilities resulting in far more infrastructure damage, loss of the fuel storage and Submarine base for example. This has introduced logistical and support issues for the USN leading up to the 1st Midway I am presenting.

The second flow on ITTL regards the Nieustralis navy (RNN). Here the dominion is a separate observer for WNT purposes, with its two BCs ITTL demilitarized and not scrapped as occurred IRL. Post war as a result, it goes down the naval aviation development line in conjunction to the theme developed by David Rowes AU. By getting two Hawkins class carrier conversions as CVLs instead of the acquiring the two County class CAs as occurred IOTL. With the invasion of Manchuria in 1932 they convert their BCs to small CVs (think HMS Furious analog), and after 1937 IOT replace the Hawkins approach Britain for the T-class CV (think something between the Colossus and Illustrious, HMS Indomitable lite, single hanger, much lighter side armor etc.). This means that with the reduced tempo of the Atlantic they agitate to move greater forces to the Pacific campaign. IRL this applied to the infantry forces deployed in the Western Desert, but it is realistic to extend this premise to the RNN carriers ITTL. This will result in a number of smaller carriers also in the Pacific theatre and it will play its part in the scenario developing.

The net result of these changes will lead to a longer and more attritional Pacific campaign in this AU, and this will represent the first of four major carrier battles in the Pacific, and by far the largest naval battle of WW2 to date. First Midway will represent the first and as can be seen by the table tendered, far the largest carrier battle of World War Two to date, where the size and power of the naval aviation represents a major change in the conduct of naval warfare.

This is the logical basis for the evolution of the seemingly outrageous force levels involved in this battle concept. But I hope you will see that there is a progression behind the events leading to the battle detailed. If you are interested, please look at the relevant stories mentioned as a basis, and this can help frame further critique when I get back and present my offering. I hope this preamble isn't too long winded and has whet your appetite for what is to come. There might be some initial delay as I'm going to be coming off a surgical procedure shortly, but still wanted to start this to have something to distract me whan I get back.

Regards T.