Edward VI of England

As Edward Tudor, King of England, lay sickly in his bed, most feared the worst. His Regent, the Duke of Northumberland, had devised a scheme to marry his son to Jane Grey, and thus have his own family rise to the throne, as a Dudley dynasty. However, as the Regent had a miracle doctor brought to the capital to prolong the King’s life through potions made of arsenic, a miracle occurred. Having been deadly ill, the young man seems to have fallen into a severe fever, and all hope seemed lost. However, within days, the fever broke, and recovery could begin.

Now, it was not until April that the King of England could leave his bed, and even then only for short periods of time. But as Edward recovered, he found the tide had turned against his Regent. The Lady Mary, his sister, had been turned away during is illness and, later, his recovery. Now unable to find any excuse to leave her out, the Duke of Northumberland hoped his continual talk of her as an unfaithful subject would hold. However, it was not to be.

The two embraced upon meeting each other for the first time in months, although the Lady Mary was forced to undergo the appropriate formalities as any English subject would to meet the King. But once they had been gone through, the young man had her rise and the siblings found a common ground as they hadn’t in many years. The talk of religion was left out, and instead, they spoke to the King’s illness and his recovery. It was a joyous occasion for the two of them, and when the King’s sister left the court again to attend to her own lands and issues, she did so laden with gifts, and with confidence that all was well between the two.

It took until July for the King of England to welcome his other sister to court, at by which time he was walking and attending the councils meetings again. As they had before is illness, the two shared a sense of formality, although there was talk of the Lady Elizabeth crying when her brother told her the story of how he had seen Heaven briefly. This was a story that the King would repeat often to guests, to remind them how close he had been to death. He often remarked that, despite how sickly he had been, God himself had willed him to live, and he had listened. Nevertheless, Elizabeth Tudor left his court as her sister had, laden with gifts and comfortable that her brother was safe.

The young King did not immediately agree to take action against the Regent that now was so unpopular he could not move safely without a full guard on employ. The affection Edward had towards the man who had taken over from his uncle was still apparent. In late July, seemingly without reason, the King gifted Northumberland with two very large grants, that seemed to many to be the next step on the continual rise for the Dudley family. The first was the grant to John Dudley to the tune of $734, as a sort of bonus for his care of the King during his illness. The second, and much more grand gift, was the bestowal of the Earldom of Leicester to the Regent’s son Guildford, who had married the Lady Jane Grey.

However, these proved not to be the next step on the ladder to greatness for the Duke, but a parting gift of sorts. The King of England would, for now, keep Northumberland close to him, but as of his 16th birthday, in October, the King felt sufficiently mature enough to take his place as the King of England with his full powers and responsibilities. Northumberland thus fell into place as his primary advisor, with his sons as members of the King’s entourage. In particular, the Earl of Leicester found himself given certain privileges, as he and his wife joined in on the revelry that became an important part of the King’s new, unrestricted court.

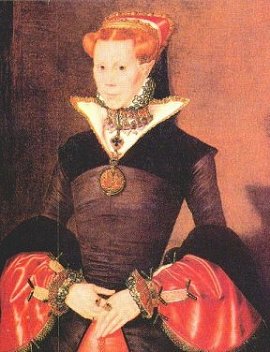

The King’s sisters also found themselves drawn into the merriment that marked the October celebrations of the King’s majority. Mary, initially, seems to have questioned her brother’s choice to begin his reign unhindered, particularly as it removed her one argument legally that kept her ignoring of his religious policies. However, the celebrations for the King’s sixteenth birthday was a chance for the 37 year old Lady Mary to dress well and dance, a pastime she enjoyed. And as religion remained a topic untouched by either of them, she felt comfortable enough.

The Lady Elizabeth, meanwhile, found that King Edward’s majority meant two things for her. An excuse to wear nice clothes and dance, and the beginning of the end of her freedom as a single woman. While the King did not immediately demand she agree to the proposed Danish match that had been proposed months previously, he agree to take the negotiations further, ending the stall they had been placed under since prior to his illness. While not pleased, the 19 year old Elizabeth found little to actually say as to the betrothal, which was yet to actually be formalized. And as the Lady Mary had found her own proposed marriage voided by the lack of funds to her dowry, the young woman remained confident that it might pass, and she might continue her freedom.

One engagement that was not in danger at this time was the proposed marriage between the King of England and the French Princess, Elisabeth de Valois. The daughter of the French King Henri II was only eight at this time, but had been betrothed to Edward since 1550, and was thus referred to by her court as the Queen of England, as Catherine of Aragon had been during her youth. The King of France sent a reminder of this to Edward VI of England, in the form of a gift to the young King: a portrait of is betrothed, standing next to a portrait of Edward. The English King returned the favour with a portrait of himself next to the portrait of Elisabeth, next to the portrait of Edward. The joke was not lost on Henri II, who commented that the likeness to the original portrait was striking.