Post 4: Skylab

“I wanted to stay up there longer. When you’re up there the thing you have the least time to do is what you like to do the most – look out the window at the earth going by at five miles per second.”

- Astronaut Jack Lousma, Commander, Skylab 5

++++++++++++++++++++

As the Soviets lauded the success of Zarya 3, the US response was already in advanced preparation. Following the landing of the Space Shuttle Columbia on its third Orbital Flight Test mission in May 1982, attention at the Cape turned to the fourth mission of the Space Transportation System: STS-4C, the first flight of the Shuttle-C heavy lifter, and its payload, Skylab-B.

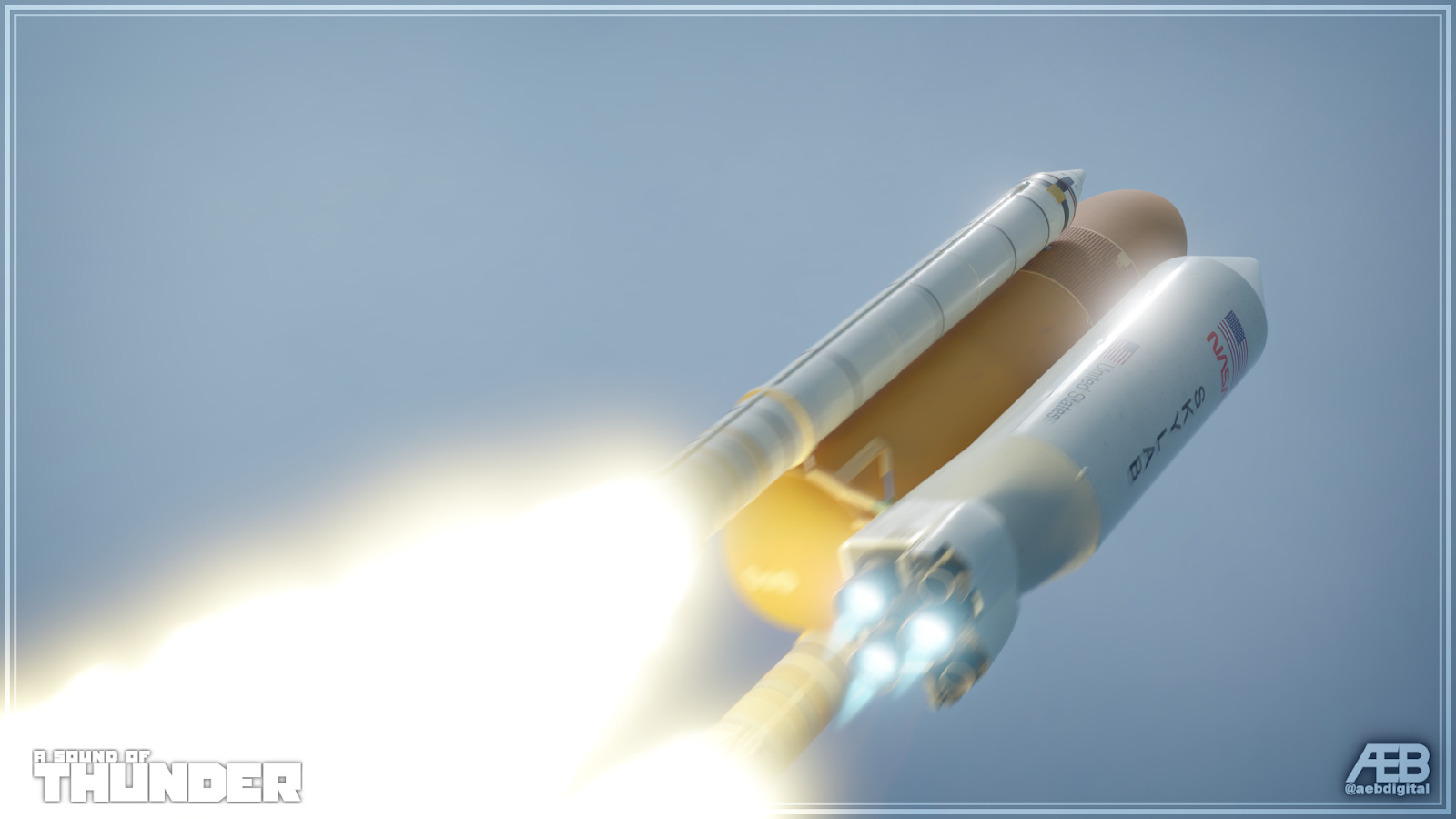

NASA had initially intended to launch the first Shuttle-C mission with a dummy payload, rather than risk their one-and-only Skylab module on the first flight. However, a combination of growing confidence in the STS stack from the first three Orbiter missions, political pressure to respond to the Soviet achievements as quickly as possible, and budget pressure from the divergence of funds to the initial phases of the Moonbase Freedom Program, led to a decision to go directly to an operational launch. This gamble paid off, and STS-4C lifted from Pad 39A on 8th July.

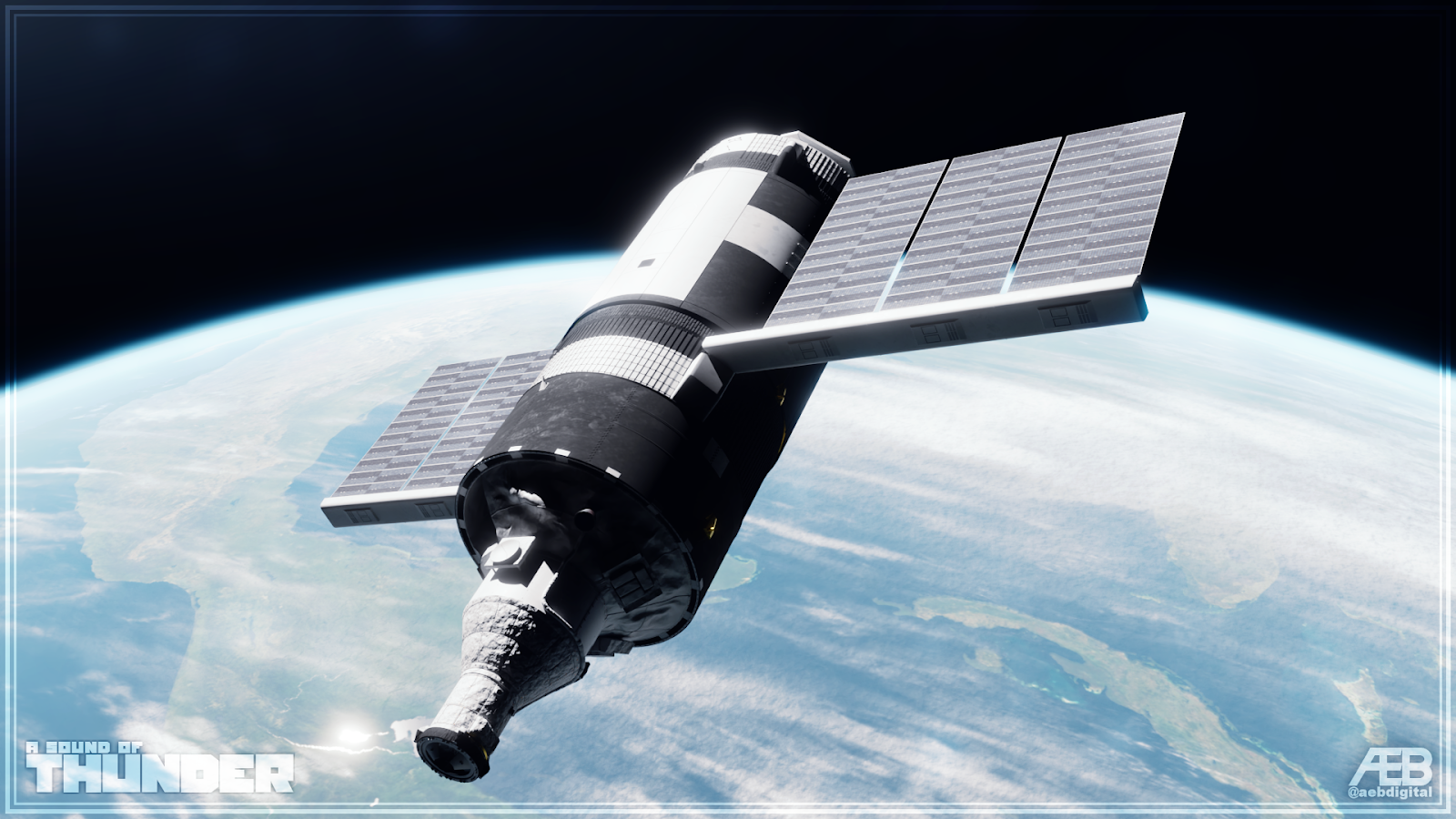

The payload module’s oversized fairing generated some dramatic shock clouds as the stack passed through Max-Q, but the structure held up, protecting the station from a repeat of the problems of Skylab-A’s launch. Eight minutes after launch, the three main engines shut down, completing their first and last mission, and the orange External Tank separated for destruction. The Propulsion Module and Payload Module continued together with the station (which was now exposed to space after the jettisoning of the Payload Module’s upper fairing) for another half-orbit, after which the Orbital Manovering System engines circularised their orbit. Following separation of the station, the OMS was fired again, putting the husk of STS-4C on course for a burial at sea in the western Pacific. Meanwhile, 400km above the surface, Skylab-B deployed its solar wings and meteoroid shield to await its crew.

That crew was carried aloft by the orbiter Columbia on what was planned to be the fourth Orbital Flight Test mission. Like the three OFTs before it, this mission would carry a crew of two, both seated in ejection seats should there be any problems with their brand new spaceship. Commanding the mission was Jack Lousma, who in addition to his involvement in the Space Shuttle test programme had spent 59 days aboard Skylab-A as part of the 1973 Skylab 3 mission. He was backed up in the pilot’s seat by Henry Hartsfield, a rookie astronaut who had been involved in the Air Force’s Manned Orbital Laboratory space station project before its cancellation. Their primary objective was to test the Shuttle’s rendezvous and docking capabilities, with a secondary objective to start the activation of Skylab-B, with both Lousma’s and Hartsfield’s experience with earlier stations expected to prove valuable in this aspect of the mission[1]. At Lousma’s insistence, NASA agreed to continue the station mission naming sequence begun with Skylab-A, and so the mission would finally have three separate designations: STS-5, OFT-4 and Skylab-5.

Columbia launched on 10th September 1982, maintaining the four month turnaround time between missions seen with the orbiter’s first three flights. After climbing to orbit, Lousma and Hartsfield spent a day in low orbit, starting up a number of experiments in the orbiter’s mid-deck and activating and checking the External Airlock and Docking System. With everything showing green, flight day 2 saw Columbia phase orbits with Skylab and begin a slow approach to bring the orbiter within 1000 feet of the station. A flyaround of the station showed it to be in good shape, with Lousma expressing particular satisfaction that the meteoroid shield had apparently deployed with no problems and both solar arrays were fully extended and undamaged. He also noted that the absence of an Apollo Telescope Mount with its windmill-like solar arrays made the station appear more compact and less cluttered than the original Skylab.

With the flyaround complete, Lousma piloted the ship on a slow approach to the station’s Docking Module. At just over 90 tonnes, Columbia actually massed more than Skylab-B, and the crew were taking no chances on this, only the fourth flight of the shuttle orbiter. The final approach speed was less than a foot per second, as Lousma eased the docking rings together, the joined spacecraft flexing slightly under the loads of contact. The docking mechanism then cranked into action, locking the two into a single entity, the heaviest structure America had ever assembled in orbit.

Columbia spent the next three days docked with Skylab, as Lousma and Hartsfield worked to activate the station. This included a transfer of 500kg of consumables and almost 200kg of experiments from the Shuttle’s mid deck to Skylab’s interior, where they would be left running for retrieval by the next mission. This task was made challenging by the tight spaces of the EADS and Skylab’s Docking Module, but once through to the main Orbital Workshop, the two astronauts found themselves presented with an abundance of room. With Skylab operating in a crew-tended mode, at least for the first few missions, the station had been launched without crew quarters or support equipment beyond the basic life support requirements. Visiting crews would live on the Shuttle orbiter, with the Workshop prioritised for experiments, similar to the way the Soviets operated Zarya with crews living out of their Slava FGBs. On this first mission, before much experiment hardware had been installed, this meant a huge volume for the two astronauts to stretch out in, a fact that they eagerly showed off during rest periods by bouncing off the Workshop walls for the cameras.

With the station activated and the first experiments installed, Columbia undocked from the station on 15th September, gliding down to a landing at Edwards Air Force Base. Officially, this marked the end of the Orbital Flight Test programme, and there was considerable pressure from both within NASA and the White House to start quickly ramping up operational missions to justify the lofty claims that had been made for the economics of the spaceplane. Administrator Borman and his Director of Shuttle Operations, Chester M. Lee, were resistant to this push, with Borman in particular remaining uncomfortable at the way the OFT programme had been cut from six flights identified in 1979 to just four. NASA Public Affairs removed the term “Operational” from their descriptions of the next few missions, using instead the nebulous term “Pre-Operational”. Although this made little practical difference - Shuttle was still declared ready to support commercial and national security customers - it had the desired effect of focusing minds within the agency on the fact that this remained an experimental vehicle, and that complacency should not be allowed to creep in.

Columbia flew again in December on STS-6, this time with a crew of four supporting the launch of two commercial communications satellites and demonstrating the first spacewalk from the Shuttle. This was followed in April 1983 by Columbia returning to Skylab on STS-7/Skylab-6, supported for the first time by the European Space Agency’s Spacelab module and an Extended Duration Orbiter pallet. Authorised for development at the start of the Skylab-B project, the EDO carried additional hydrogen and oxygen for the orbiter’s fuel cells to extend the time Columbia could remain aloft, a capability considered vital to get the most value out of station visits. The crew for this mission was expanded to six, including ESA astronaut Ulf Merbold, and America’s first woman in space, Sally Ride. The crew spent ten days docked with Skylab, performing joint experiments in the Spacelab and Orbital Workshop modules, retrieving data samples from the Skylab-5 experiments, and setting up equipment for the next period of uncrewed operations. Even with the larger crew, the workload was punishing, and many items ended up being dropped from the checklist as delays to early tasks had knock-on effects throughout the schedule.

June 1983 saw the debut of the orbiter Challenger on STS-8, delivering another two commercial satellites and an experimental Department of Defense payload. The introduction of Challenger provided a welcome breather for Columbia to undergo a more extensive maintenance period, while Challenger returned to space in September, launching a NASA data relay satellite before continuing on to Skylab-B for a stay of twelve days, with Columbia returning to flight in November.

1984 saw another five Shuttle missions, with OV-103 Discovery joining the fleet at the end of the year. However, this was still not enough to meet the commitments that had been made to the Shuttle’s various customers and stakeholders. With the final two orbiters, Atlantis and Enterprise, expected to enter service in 1985, the White House was pressuring NASA to launch at least once a month. With a long list of anomalies still occurring on every mission, Borman continued to push back on these demands, leading to frequent clashes with his political masters.

In an attempt to ease the pressure, Borman backed a DoD proposal to maintain the existing stable of expendable launch vehicles as a supplement to the Shuttle, enabling high priority national security payloads to be launched without having to wait for a slot on the Shuttle. To make the business case close with the contractors, Borman went further and agreed with a White House proposal to formally end Shuttle’s monopoly on US commercial launchers, enabling Atlas and Titan rockets to carry commercial satellites. This marked a reversal of the longstanding policy of relying solely on Shuttle, and was hugely controversial within NASA and Congress.

The ranks of Borman’s enemies grew, and he faced growing attacks in the press for a perceived sluggishness in NASA’s response to continued Soviet success. Project Freedom, NASA’s plan to return to the Moon, was moving forward, but while NASA was signing contracts and conducting reviews, the Soviets were continuing with ever-more-impressive Zvezda missions. As NASA made brief sorties to Skylab-B every few months, the Soviets had kept Zarya 3 permanently crewed for almost three years. At a time of ballooning US deficits, what the hell was NASA doing with all that money, anyway?

By the time Reagan began campaigning in earnest for re-election in the summer of 1984, Borman had already privately decided to leave NASA. The constant political battles, both internal and external, had taken their toll, and the prospect of another four years of the same was not appealing. With the Shuttle now launching regularly (even if not as frequently as some liked), with Borman’s safety-first culture bedded in, and with the Freedom lunar programme off to a good start, the Administrator felt that he had done all he could to put the agency back on track. Following Reagan’s re-election in November, Borman informed the President of his decision, and in January 1985 he formally left his role as NASA Administrator.

++++++++++++++++++++

[1] IOTL Lousma commanded STS-3 while Hartfield was the pilot on STS-4. Lousma was also in the frame to

pilot the shuttle on the Skylab rescue mission STS-2A.