You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Most Glorious Revolution: Savoyard Spain

- Thread starter morbidteaparty

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 24 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The Eagle and the Bull: The Americas and Spain, 1884-1885 A Surprising Spirit of Radicalism: The Second Cánovas Ministry and Initial Domestic Policy, 1884-1885 Both of the Centre and the Periphery, 1884-86 Scandal, Sedition and Strife: The Collapse of the Cánovas Ministry Turbulence and Turmoil, 1887 The King is Dead, Long Live the King 1887-88 A Year of Lead: Colonial Pogroms and Metropole Repression, 1888 The Return to Stability: The Evergreen Cánovas, 1888

Both of the Centre and the Periphery, 1884-86

Initially concerned with domestic matters upon his return to the premiership, Cánovas found himself increasingly drawn into matters concerning Spain’s overseas territories. The economic crisis which had hit Cuba showed no signs of abating, and the moribund nationalists who had gone into exile following the Historic Compromise had begun to return to eminence. The abolition of slavery in the 1870s had seen a shift in demographics as former slaves joined the rural classes in large numbers, while a significant minority migrated to the expanding cities. As a result, the number of campesinos and tenant farmers began to increase, while the old colonial elite began to move to the cities, joining the burgeoning middle classes. The collapse of the sugar price in the aftermath of the volatile tariff wars between Spain and the United States in the 1880s saw the number of sugar mills decline, with production increasingly concentrated in the hands of a smaller number of producers. The increasing influence of American capital in the island’s economy, mainly in sugar, tobacco and mining concerned the Spanish government, with tensions between the American investors and the Cuban colonial government increasing tensions between Washington and Madrid. [1] Spain’s continued involvement in the Americas further soured Hispano-American relations, as President Iglesias of Mexico sought to strengthen the burgeoning metallurgical industries which were sprouting in the north, while seeking a counterweight to the influence of the Americans, which saw him turn to the Franco-Spanish businessmen who had established themselves in Mexico during the 1870s. While Spanish influence remained small, the presence of Spanish capital in Baja California was a cause of concern to the Cleveland administration, who like previous administrations viewed the continued Spanish presence in the Caribbean as a block to American territorial ambitions.

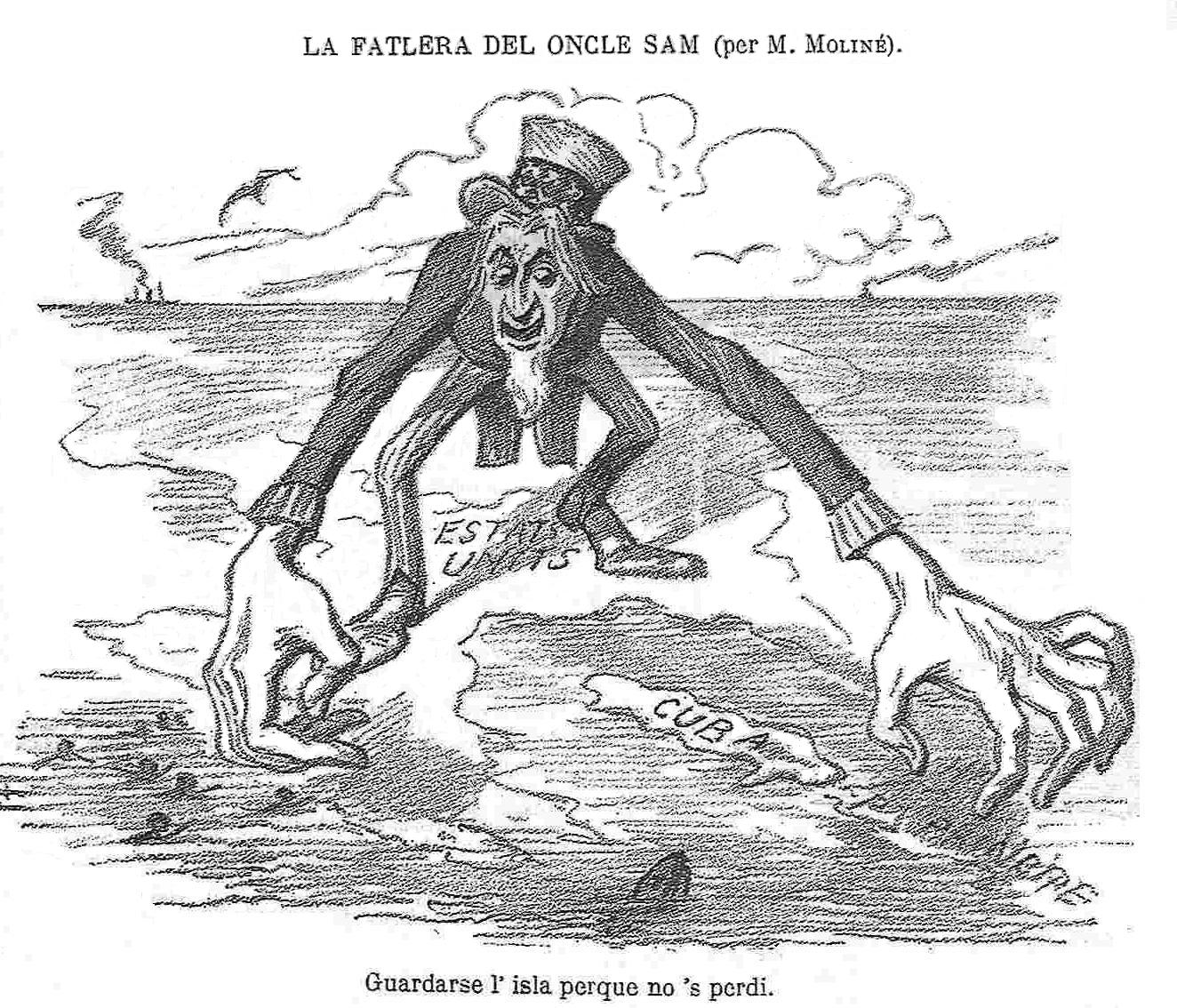

A Catalan cartoon (1886) satirising American interest in Cuba

In the Philippines, the situation had begun to stabilise following the suppression of the revolt in Mindanao during the early 1880s, with the Captain-Generalcy of Carlos María de la Torre having secured a degree of limited reform in the colony. Tentative moves had been made towards granting the archipelago a limited degree of autonomy under the previous Liberal ministries, though plans to secularise the churches were abandoned under Cánovas. The colonial authorities, under the broad supervision of Colonial Secretary Antonio Maura, were granted a large degree of autonomy in regards to their running of the archipelago’s affairs. Maura, a reformist supporter of Cánovas, adapted what became known as the Maura Law which established municipal government [2] in the Philippines, establishing municipal councils with a degree of power over local affairs, though stopping well short of granting Home Rule, as had begun to be increasingly demanded by local reformers. The colonial government under de la Torre had begun several infrastructure projects, including the construction of a railway network in Luzon. In Manila, a tramcar network was gradually developed, though its progress was marked by corruption and pressganged labour, as thousands of Chinese and Malay workers arrived alongside mass arrivals from the poorer parts of the archipelago, increasing ethnic tensions within the capital itself. [3] These developments in Spain’s long held possessions in the Caribbean and Asia were mirrored somewhat by developments in its newer territories in Africa. Spain’s territory in Rio Muni remained largely underdeveloped, though San Amadeo gradually began to grow in size as a trade hub for the Congo Basin. In Morocco, the Spanish military found itself fighting small skirmishes with the local Rif tribesmen, though there were no real plans in the government to fully pacify the area.

19th Century Manila

Cánovas continued the broad consensus in terms of foreign policy, which generally pursued neutrality in regards to continental affairs. Spain’s reputation as a mediator, saw her arbitrate (alongside Germany) the 1886 Treaty of London which saw Portugal and Britain reach a settlement over the status of Zambezia. [4] Spain’s warm relations with Italy saw it join the Latin Monetary Union, having generally pursued the union’s currency policies since the early 1870s, though this would later lead to currency problems given the Union’s policies. [5] The increasing economic ties between Spain and the union, saw an increasing split over foreign policy as the cabinet began to split into Anglophile and Francophile wings [6], with smaller minorities in favour of closer ties with Germany and Italy. Cánovas, despite his strong favour for neutrality began to view the relations with Italy as crucial to Spain’s interests given their mutual concerns in the Mediterranean and their previous cooperation in international affairs, as well as the family ties between the two kings. While no formal treaty of alliance was proposed, the strengthening of ties between the two was viewed favourably by both Cánovas and Italian Prime Minister Agostino Depretis, for different reasons. [7] While a man who wished to be defined by his political acumen in building a Spanish state, Cánovas found himself increasingly drawn into foreign affairs, as Spain gradually began to shed her insularity.

BRIEF NOTES

[1] The colonial government’s enforcement of stringent commercial regulations on foreign capital and investment in both Cuba and Puerto Rico were aimed to reduce American influence and dependence in both islands domestic economies. The increasing monopolisation of the depressed sugar economy in Cuba by American capital alarmed Madrid who imposed stricter protectionist measures as a result. While the tensions were mostly due to economic concerns, Spain’s wariness around American expansionist ambitions ensured that the local garrisons were well manned, while the presence of a detachment of the Armada Española was aimed as a deterrent.

[2] The law established a tripartite system of local governance: tribunals which were to oversee local legal matters, the municipalities and provincial councils who were granted some moderate powers in regards to local administration.

[3] The influx of imported labourers as well as arrivals from culturally distinct areas such as Mindanao caused tensions in Luzon, particularly over employment with several anti-Chinese organisations establishing themselves as a result. While not yet threatening to break out into violence, the simmering tensions remained a source of concern for the colonial authorities.

[4] Serpa Pinto, who had led Portuguese expeditions around Lake Nyasa and the Zambezi had established treaties with several of the tribes in the Lake Nyasa region given Portugal some claims to that area. While the issue had not been resolved at the Berlin Conference, several rounds of negotiations eventually saw the territories around the Shire Highlands and Lake Nyasa ceded to the Portuguese in exchange for renunciation of all claims on the territories in the Zambezi. While the treaty was not viewed popularly by the Portuguese public, who viewed the renunciation of the claims as a capitulation to British interests, the government viewed it as a success as it extended Portuguese territory at minimal cost.

[5] Fluctuations in the value of the French franc, to which the member currencies were pegged stressed the currency union, as did the respective fluctuations in both gold and silver, for while the union was de facto gold standard it had originated with policies of bimetallism. The failure of the union to outlaw the printing of paper money based on the bimetallic currency was exploited by both France and Italy who printed banknotes based on it to fund their own endeavours, forcing other member nations to bear some of the cost of their fiscal extravagances by issuing notes backed by their own currencies.

[6] The split was largely between those who favoured closer relations with the United Kingdom, as British investment had played a significant role in Spain’s industrial development and those who favoured a military alliance with France in order to secure Spain’s colonial interests, particularly as France had re-emerged as a major power on the international scene, having finally stabilised by the 1880s. These cabinet tensions would dog Cánovas and his ministry, though for the moment his policy of neutrality remained the dominant voice of Spanish interactions with the European powers.

[7] Cánovas viewed closer relations with Italy as a useful buffer to France, who he viewed with suspicion, particularly in the aftermath of the tariff wars of the late 1870s. The Italian establishment in Eritrea had proven useful for Spanish shipping to the Philippines, as it became a coaling station on the Red Sea. For Depretis, closer ties to Spain ensured that Italy remained less isolated and less dependent on France or Germany, allowing him to pursue a more independently minded foreign policy than previous governments.

A Catalan cartoon (1886) satirising American interest in Cuba

In the Philippines, the situation had begun to stabilise following the suppression of the revolt in Mindanao during the early 1880s, with the Captain-Generalcy of Carlos María de la Torre having secured a degree of limited reform in the colony. Tentative moves had been made towards granting the archipelago a limited degree of autonomy under the previous Liberal ministries, though plans to secularise the churches were abandoned under Cánovas. The colonial authorities, under the broad supervision of Colonial Secretary Antonio Maura, were granted a large degree of autonomy in regards to their running of the archipelago’s affairs. Maura, a reformist supporter of Cánovas, adapted what became known as the Maura Law which established municipal government [2] in the Philippines, establishing municipal councils with a degree of power over local affairs, though stopping well short of granting Home Rule, as had begun to be increasingly demanded by local reformers. The colonial government under de la Torre had begun several infrastructure projects, including the construction of a railway network in Luzon. In Manila, a tramcar network was gradually developed, though its progress was marked by corruption and pressganged labour, as thousands of Chinese and Malay workers arrived alongside mass arrivals from the poorer parts of the archipelago, increasing ethnic tensions within the capital itself. [3] These developments in Spain’s long held possessions in the Caribbean and Asia were mirrored somewhat by developments in its newer territories in Africa. Spain’s territory in Rio Muni remained largely underdeveloped, though San Amadeo gradually began to grow in size as a trade hub for the Congo Basin. In Morocco, the Spanish military found itself fighting small skirmishes with the local Rif tribesmen, though there were no real plans in the government to fully pacify the area.

19th Century Manila

Cánovas continued the broad consensus in terms of foreign policy, which generally pursued neutrality in regards to continental affairs. Spain’s reputation as a mediator, saw her arbitrate (alongside Germany) the 1886 Treaty of London which saw Portugal and Britain reach a settlement over the status of Zambezia. [4] Spain’s warm relations with Italy saw it join the Latin Monetary Union, having generally pursued the union’s currency policies since the early 1870s, though this would later lead to currency problems given the Union’s policies. [5] The increasing economic ties between Spain and the union, saw an increasing split over foreign policy as the cabinet began to split into Anglophile and Francophile wings [6], with smaller minorities in favour of closer ties with Germany and Italy. Cánovas, despite his strong favour for neutrality began to view the relations with Italy as crucial to Spain’s interests given their mutual concerns in the Mediterranean and their previous cooperation in international affairs, as well as the family ties between the two kings. While no formal treaty of alliance was proposed, the strengthening of ties between the two was viewed favourably by both Cánovas and Italian Prime Minister Agostino Depretis, for different reasons. [7] While a man who wished to be defined by his political acumen in building a Spanish state, Cánovas found himself increasingly drawn into foreign affairs, as Spain gradually began to shed her insularity.

BRIEF NOTES

[1] The colonial government’s enforcement of stringent commercial regulations on foreign capital and investment in both Cuba and Puerto Rico were aimed to reduce American influence and dependence in both islands domestic economies. The increasing monopolisation of the depressed sugar economy in Cuba by American capital alarmed Madrid who imposed stricter protectionist measures as a result. While the tensions were mostly due to economic concerns, Spain’s wariness around American expansionist ambitions ensured that the local garrisons were well manned, while the presence of a detachment of the Armada Española was aimed as a deterrent.

[2] The law established a tripartite system of local governance: tribunals which were to oversee local legal matters, the municipalities and provincial councils who were granted some moderate powers in regards to local administration.

[3] The influx of imported labourers as well as arrivals from culturally distinct areas such as Mindanao caused tensions in Luzon, particularly over employment with several anti-Chinese organisations establishing themselves as a result. While not yet threatening to break out into violence, the simmering tensions remained a source of concern for the colonial authorities.

[4] Serpa Pinto, who had led Portuguese expeditions around Lake Nyasa and the Zambezi had established treaties with several of the tribes in the Lake Nyasa region given Portugal some claims to that area. While the issue had not been resolved at the Berlin Conference, several rounds of negotiations eventually saw the territories around the Shire Highlands and Lake Nyasa ceded to the Portuguese in exchange for renunciation of all claims on the territories in the Zambezi. While the treaty was not viewed popularly by the Portuguese public, who viewed the renunciation of the claims as a capitulation to British interests, the government viewed it as a success as it extended Portuguese territory at minimal cost.

[5] Fluctuations in the value of the French franc, to which the member currencies were pegged stressed the currency union, as did the respective fluctuations in both gold and silver, for while the union was de facto gold standard it had originated with policies of bimetallism. The failure of the union to outlaw the printing of paper money based on the bimetallic currency was exploited by both France and Italy who printed banknotes based on it to fund their own endeavours, forcing other member nations to bear some of the cost of their fiscal extravagances by issuing notes backed by their own currencies.

[6] The split was largely between those who favoured closer relations with the United Kingdom, as British investment had played a significant role in Spain’s industrial development and those who favoured a military alliance with France in order to secure Spain’s colonial interests, particularly as France had re-emerged as a major power on the international scene, having finally stabilised by the 1880s. These cabinet tensions would dog Cánovas and his ministry, though for the moment his policy of neutrality remained the dominant voice of Spanish interactions with the European powers.

[7] Cánovas viewed closer relations with Italy as a useful buffer to France, who he viewed with suspicion, particularly in the aftermath of the tariff wars of the late 1870s. The Italian establishment in Eritrea had proven useful for Spanish shipping to the Philippines, as it became a coaling station on the Red Sea. For Depretis, closer ties to Spain ensured that Italy remained less isolated and less dependent on France or Germany, allowing him to pursue a more independently minded foreign policy than previous governments.

Hope we get a chapter soon exploring the relationship between Spain, and Italy. Would love to see how the brother monarchs relationship evolves.

I'm loosing track of my "Glorious (x)" Spain timelines, did the Dominican Republic rejoin Spain in this one or was that just in the Hohenzollern Spain ones?

I'm loosing track of my "Glorious (x)" Spain timelines, did the Dominican Republic rejoin Spain in this one or was that just in the Hohenzollern Spain ones?

The Dominican Republic joined Spain in the Hohenzollern ones

In this Savoyard World, she merely suffered some gunboat diplomacy

The Dominican Republic joined Spain in the Hohenzollern ones

In this Savoyard World, she merely suffered some gunboat diplomacy

Cheers, sorry if that question was seen as offensive to be confusing such timelines.

Scandal, Sedition and Strife: The Collapse of the Cánovas Ministry

While secure in his parliamentary majority, Cánovas would find his government beset by scandal and crisis as Spain approached the 1890s. While the effects of the agrarian depression had been mitigated in the south somewhat by the introduction of agrarian subsidies, the anarchist movement remained deeply ingrained in the south, despite widespread state repression. An increase of rents by landowners in Huelva province in Andalusia provided the spark for a series of demonstrations, as peasant squatters seized land and large crowds demonstrated for work and against local misgovernment, while the hated tax offices were burnt down. The violence was greeted with outrage within the government, who under intense pressure from the local landowners ordered the deployment of the army to reinforce the embattled Guardia Civil. Clashes between soldiers and peasants in the city of Huelva resulted in thirteen deaths, and in response anarchist bombings in Andalusia increased. The uprising would eventually be suppressed by the army, with its leaders arrested and sentenced under a military tribunal. The sentences imposed were lengthy, with each defendant sentenced to twelve years in prison, which provoked an angry response in the radical press, and angered many with liberal sympathies, as the spectre of land reform returned to haunt the political establishment.

Clashes between police and protestors, Huelva

The government, and the Liberal opposition, would further be hit by the revelation of a financial scandal which implicated leading members of both parties, as it was revealed that both Herrera and Cánovas had suppressed a report which investigated a major bank, Banco Madrid. The report had found that the bank had serious irregularities in its administration and accounts, while the bank had further been hit by the liabilities it incurred through its loaning of large sums to several industrial enterprises and property developers, who had subsequently bankrupted following the collapse of the speculative bubble in late 1886. The report had also found that the bank had made substantive payments to various politicians including leading members of both parties, though Cánovas himself was not directly implicated. The scandal was gleefully published in the radical press, and was soon being widely published across the country’s newspapers, forcing the government to form a commission to investigate the ailing bank. Their report confirmed the seriousness of the bank’s situation, as it had vast debts and cooked accounts. The publication of the report would see the bank’s president and directors arrested and tried for embezzlement and other fraudulent practices, following the bank’s liquidation in late 1887.

A cartoon satirising both the Liberals and the Conservatives in anarchist magazine El Porvenir

While Cánovas himself was not implicated, the scandal would both topple his government and wound the opposition as leading members of his government and the Liberal ministries of Sagasta and Herrera were revealed to have accepted bribes in the form of election expenses. The embroilment of the opposition in the scandal had initially secured his survival in the Cortes, his dogged refusal to sanction a parliamentary inquiry into the scandal, and the revelation that he had suppressed the initial report provoked widespread anger, and he eventually resigned following a vote of no confidence triggered by the abstention of several Conservative MPs, a slight Cánovas never forgot. The scandal, and the uproar surrounding bribes and cover-ups that had appeared in its wake, discredited both the Liberals and Conservatives and the banks, and substantially tarnished the reputations of both Cánovas and Sagasta who would find their respective political influence curtailed.

Clashes between police and protestors, Huelva

The government, and the Liberal opposition, would further be hit by the revelation of a financial scandal which implicated leading members of both parties, as it was revealed that both Herrera and Cánovas had suppressed a report which investigated a major bank, Banco Madrid. The report had found that the bank had serious irregularities in its administration and accounts, while the bank had further been hit by the liabilities it incurred through its loaning of large sums to several industrial enterprises and property developers, who had subsequently bankrupted following the collapse of the speculative bubble in late 1886. The report had also found that the bank had made substantive payments to various politicians including leading members of both parties, though Cánovas himself was not directly implicated. The scandal was gleefully published in the radical press, and was soon being widely published across the country’s newspapers, forcing the government to form a commission to investigate the ailing bank. Their report confirmed the seriousness of the bank’s situation, as it had vast debts and cooked accounts. The publication of the report would see the bank’s president and directors arrested and tried for embezzlement and other fraudulent practices, following the bank’s liquidation in late 1887.

A cartoon satirising both the Liberals and the Conservatives in anarchist magazine El Porvenir

While Cánovas himself was not implicated, the scandal would both topple his government and wound the opposition as leading members of his government and the Liberal ministries of Sagasta and Herrera were revealed to have accepted bribes in the form of election expenses. The embroilment of the opposition in the scandal had initially secured his survival in the Cortes, his dogged refusal to sanction a parliamentary inquiry into the scandal, and the revelation that he had suppressed the initial report provoked widespread anger, and he eventually resigned following a vote of no confidence triggered by the abstention of several Conservative MPs, a slight Cánovas never forgot. The scandal, and the uproar surrounding bribes and cover-ups that had appeared in its wake, discredited both the Liberals and Conservatives and the banks, and substantially tarnished the reputations of both Cánovas and Sagasta who would find their respective political influence curtailed.

Turbulence and Turmoil, 1887

The aftermath of the Banco Madrid scandal saw Sagasta return to the premiership at the head of the “Progressist coalition” between the Liberal Party and the Radicals, led by the ever-unpredictable Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla. [1] Relations between the two parties in government would remain tense for the duration of Sagasta’s ministry, fuelled primarily through the personal enmity of Sagasta and Zorrilla, as well as historical grievances derived from the splits of the Progressive Party.

The new government instituted a new penal code under the supervision of Cristino Martos [2] which recognised the right to strike and abolished forced labour as a criminal sentence outside of wartime, while the garrotte which had been used in executions since the 1820s was outlawed, though capital punishment itself was not abolished. [3] Local government reform built upon the 1833 administrative divisions of Javier de Burgos, establishing elected provincial councils and replacing the previous system of appointment by central government. Plans to reform the constitution and strengthen the power of the executive at the expense of parliament were abandoned following heavy opposition from the Radical contingent in government, who viewed such an attempt as harkening back to the old days of enlightened despotism, which had marred the Isabelline period.

Cristino Martos, author of the legal reforms of the late 1880s

Acutely aware of the deep resentment towards the imposition of martial law in Andalusia, Sagasta ended the military campaign against anarchists in the region, and pardoned and released many of the accused anarchists from prison, though this period of clemency was not extended to its leaders. Under pressure from the radical elements in his government, Sagasta proposed further land reforms, which would build upon the limited reforms introduced by earlier governments in the decade. The Land Acts (colloquially known as the Canalejas Code after José Canalejas the Minister for Agriculture) proposed to increase the security and rights of tenants through several measures:

· That tenants had the right to a reasonable security of tenure so long as they paid rent, while also granting them the right to sell their holding to another tenant acceptable to the landlord.

· Uncultivated land and large estates with absentee landowners would be taken over by the state.

· These new lands would be rented out on long leases in medium sized holdings, while leaseholders would be given reduced credit and tax concessions.

The legislation angered both the landowners and the Conservative opposition, headed by Marcelo Azcárraga who had succeeded Cánovas as party leader. While the parliamentary debate turned heated, with Socialist deputy Francisco Ferrer [4] censured for declaring that the Conservative opposition had “no convictions, for if they had they would declare this chamber null and void and raze it to the ground!” The land reform was eventually defeated in the senate, which held a Conservative majority. [5] The failure of the reform resulted in mass protests, and the spectre of violent instability which had coloured the country throughout the decade appeared to have reappeared. The government’s problems were further compounded by the threat of a mutiny in the Philippines over the low pay for colonial troops.

While these troubles convulsed the government, it would be greeted by worse news, news that would be a source of great mourning. Amadeus, whose reign had seen him become a widely popular monarch despite his initial status as an outsider, had died at the young age of forty-two from tuberculosis, which was greeted with widespread shock throughout the country.

Amadeus I, King of Spain (1870-1887)

The king’s death and funeral saw widespread mourning, with large crowds turning out to pay their respects in Madrid as he was interred in a specially built crypt. A calm man, who had arrived as a young foreigner to take the throne in 1870, his patience and support of the constitutional order secured for him a degree of fondness not extended to his predecessor. For many, looking at the carriage as it passed carrying his remains, it felt like the end of an era, one that Spain might no longer be able to navigate.

BRIEF NOTES

[1] Zorrilla, who had served in the governments of both Serrano and Prim during the early years of the Savoyard state had long been known to hold radical republican views, which often put him at odds with the “constitutionalist parties” who had alternated government since 1870. Nevertheless he was a friend of Amadeus and despite his own personal republicanism had supported Prim’s offer of the Spanish crown to the Italian prince. His personal enmity with Sagasta would ensure that the coalition formed between the two to form a government of unity was fraught with tensions.

[2] Martos, a jurist and radical had long been an ally of Zorrilla, though the two men were not personally close. A committed democrat he had also served as Mayor of Madrid from 1874-1880, and had argued persuasively in cabinet for the democratisation of local politics, leading to the reform of local governance undertaken by the Sagasta government.

[3] The list of crimes for which capital punishment could be used as a sentence for were reduced to treason and murder, while the use of the garrotte was phased out and replaced by shooting or hanging as forms of execution, while public executions were banned (making de jure practices which had largely evolved during the post-revolutionary period.

[4] Ferrer, an educator and committed anarchist had joined the PSE in Barcelona in the early 1880s, and had been elected as a deputy in the 1887 election. Known for his fiery oratory, his anarchist beliefs often put him at odds with the predominately Marxist socialists.

[5] The senate’s fierce opposition to the bill would see tensions between the Conservative led upper house and the government reach boiling point with reports of violence between Liberal and Conservative senators, and the arrest of a Radical senator for attempting to carry a pistol into a debate. While the senate had less power than the lower house, the Conservative majority in the upper house would ensure that Sagasta’s legislative ambitions would be hard to fulfil.

The new government instituted a new penal code under the supervision of Cristino Martos [2] which recognised the right to strike and abolished forced labour as a criminal sentence outside of wartime, while the garrotte which had been used in executions since the 1820s was outlawed, though capital punishment itself was not abolished. [3] Local government reform built upon the 1833 administrative divisions of Javier de Burgos, establishing elected provincial councils and replacing the previous system of appointment by central government. Plans to reform the constitution and strengthen the power of the executive at the expense of parliament were abandoned following heavy opposition from the Radical contingent in government, who viewed such an attempt as harkening back to the old days of enlightened despotism, which had marred the Isabelline period.

Cristino Martos, author of the legal reforms of the late 1880s

Acutely aware of the deep resentment towards the imposition of martial law in Andalusia, Sagasta ended the military campaign against anarchists in the region, and pardoned and released many of the accused anarchists from prison, though this period of clemency was not extended to its leaders. Under pressure from the radical elements in his government, Sagasta proposed further land reforms, which would build upon the limited reforms introduced by earlier governments in the decade. The Land Acts (colloquially known as the Canalejas Code after José Canalejas the Minister for Agriculture) proposed to increase the security and rights of tenants through several measures:

· That tenants had the right to a reasonable security of tenure so long as they paid rent, while also granting them the right to sell their holding to another tenant acceptable to the landlord.

· Uncultivated land and large estates with absentee landowners would be taken over by the state.

· These new lands would be rented out on long leases in medium sized holdings, while leaseholders would be given reduced credit and tax concessions.

The legislation angered both the landowners and the Conservative opposition, headed by Marcelo Azcárraga who had succeeded Cánovas as party leader. While the parliamentary debate turned heated, with Socialist deputy Francisco Ferrer [4] censured for declaring that the Conservative opposition had “no convictions, for if they had they would declare this chamber null and void and raze it to the ground!” The land reform was eventually defeated in the senate, which held a Conservative majority. [5] The failure of the reform resulted in mass protests, and the spectre of violent instability which had coloured the country throughout the decade appeared to have reappeared. The government’s problems were further compounded by the threat of a mutiny in the Philippines over the low pay for colonial troops.

While these troubles convulsed the government, it would be greeted by worse news, news that would be a source of great mourning. Amadeus, whose reign had seen him become a widely popular monarch despite his initial status as an outsider, had died at the young age of forty-two from tuberculosis, which was greeted with widespread shock throughout the country.

Amadeus I, King of Spain (1870-1887)

The king’s death and funeral saw widespread mourning, with large crowds turning out to pay their respects in Madrid as he was interred in a specially built crypt. A calm man, who had arrived as a young foreigner to take the throne in 1870, his patience and support of the constitutional order secured for him a degree of fondness not extended to his predecessor. For many, looking at the carriage as it passed carrying his remains, it felt like the end of an era, one that Spain might no longer be able to navigate.

BRIEF NOTES

[1] Zorrilla, who had served in the governments of both Serrano and Prim during the early years of the Savoyard state had long been known to hold radical republican views, which often put him at odds with the “constitutionalist parties” who had alternated government since 1870. Nevertheless he was a friend of Amadeus and despite his own personal republicanism had supported Prim’s offer of the Spanish crown to the Italian prince. His personal enmity with Sagasta would ensure that the coalition formed between the two to form a government of unity was fraught with tensions.

[2] Martos, a jurist and radical had long been an ally of Zorrilla, though the two men were not personally close. A committed democrat he had also served as Mayor of Madrid from 1874-1880, and had argued persuasively in cabinet for the democratisation of local politics, leading to the reform of local governance undertaken by the Sagasta government.

[3] The list of crimes for which capital punishment could be used as a sentence for were reduced to treason and murder, while the use of the garrotte was phased out and replaced by shooting or hanging as forms of execution, while public executions were banned (making de jure practices which had largely evolved during the post-revolutionary period.

[4] Ferrer, an educator and committed anarchist had joined the PSE in Barcelona in the early 1880s, and had been elected as a deputy in the 1887 election. Known for his fiery oratory, his anarchist beliefs often put him at odds with the predominately Marxist socialists.

[5] The senate’s fierce opposition to the bill would see tensions between the Conservative led upper house and the government reach boiling point with reports of violence between Liberal and Conservative senators, and the arrest of a Radical senator for attempting to carry a pistol into a debate. While the senate had less power than the lower house, the Conservative majority in the upper house would ensure that Sagasta’s legislative ambitions would be hard to fulfil.

Gasp*

Amedeos Nooooooo! well there goes a mighty fine fellow, I hope we get to see his successor im the next chapter.

Amedeos Nooooooo! well there goes a mighty fine fellow, I hope we get to see his successor im the next chapter.

The King is Dead, Long Live the King 1887-88

While the coronation of the new king had provided a brief lull for Sagasta, his government would soon find embroiled in various quagmires. Attempts to resolve the parliamentary standoff over the proposed land reforms had ended in a defeat which had brought mobs onto the streets, and further increased the strain on the marriage of convenience between himself and Zorrilla. A financial crisis caused in part by the collapse of the Banco de Madrid further exacerbated the situation, leaving the government with a high budget deficit. The Finance Minister, Segismondo Moret [1] introduced higher taxation on alcohol and cotton while imposing an increased tariff on cereals, while simultaneously cutting public expenditure which gradually reduced the deficit, though it drew strong criticism from the more radical elements within the government, as well as a private rebuke from Sagasta who wished to pursue a programme of public works which soured the relationship between himself and Moret. [2]

Segismondo Moret, Minister of Finance

In the Philippines, long simmering resentments on the part of colonial troops over their low pay and poor treatment at the hands of Spanish officers [3] erupted into open mutiny as troops stationed in the island of Mindanao seized control of their barracks on the outskirts of the city of Zamboanga, executing two of the most hated officers and taking the bulk of the Spaniards stationed there as prisoners. Due to the poverty of communications in the area, the news of the mutiny reached Manila four days later, sparking fears amongst the colonial authorities that the largely unpacified region had erupted into insurrection. An expeditionary force under the command of Filipino colonel Ferdinand La Madrid [4] besieged the fort eventually forcing a surrender, though wary of enflaming similar discontent amongst the broader ranks of the colonial garrisons, summary executions [5] were not enforced. The majority of the mutineers were instead imprisoned for varying terms on the islands of Yap and Guam. While the mutiny itself was successfully suppressed it did provide the catalyst for the colonial authorities (tacitly supported by Madrid) to enact several reforms in regards to military reorganisation and colonial administration. [6]

Sagasta’s attempts to force through his legislative agenda were frustrated by both the upper house and his government’s small and fractious majority. Having failed to pass legislation on social welfare and faced with the prospect that the left of his party would rebel and ally with the opposition in voting against Moret’s proposed budget, pre-empted the collapse of his government by resigning and asking the young king to dissolve the Cortes for the first time in his reign.

As he left the royal residence he reflected wryly it probably would not be the last.

BRIEF NOTES

[1] Moret had gradually built a power base amongst the rightist faction of the Liberals and had emerged as a threat to Sagasta’s hold over the party. His appointment as Finance Minister was largely viewed as a sop to the rightists at the expense of the party’s left and exposed the depths of the party’s factionalism.

[2] Moret famously criticised the general reliance on public works as a way to solve financial crises, stating in a parliamentary debate that “to construct railways where there is no trade is like giving a spoon to a man who has nothing to eat.”

[3] This included a refusal to grant Muslim troops the same religious status as their Christian counterparts, while both pay and promotion prospects remained low. The general lack of officers who spoke the same language as their troops also hindered relations.

[4] La Madrid had been one of the first native Filipinos to advance to a high rank amongst the officer corps and was widely respected within the colonial establishment as a man of action.

[5] While De La Torre’s earlier reforms had aimed to restrict the practice it as widely used in the often-brutal colonial wars that scarred the archipelago during the period.

[6] The reforms included increased pay for local troops and the granting of equal religious rights to Muslim and Buddhist soldiers. The civil service and colonial bureaucracy were opened up to the local population resulting in an increased Filipino middle class within the colonial cities.

Segismondo Moret, Minister of Finance

In the Philippines, long simmering resentments on the part of colonial troops over their low pay and poor treatment at the hands of Spanish officers [3] erupted into open mutiny as troops stationed in the island of Mindanao seized control of their barracks on the outskirts of the city of Zamboanga, executing two of the most hated officers and taking the bulk of the Spaniards stationed there as prisoners. Due to the poverty of communications in the area, the news of the mutiny reached Manila four days later, sparking fears amongst the colonial authorities that the largely unpacified region had erupted into insurrection. An expeditionary force under the command of Filipino colonel Ferdinand La Madrid [4] besieged the fort eventually forcing a surrender, though wary of enflaming similar discontent amongst the broader ranks of the colonial garrisons, summary executions [5] were not enforced. The majority of the mutineers were instead imprisoned for varying terms on the islands of Yap and Guam. While the mutiny itself was successfully suppressed it did provide the catalyst for the colonial authorities (tacitly supported by Madrid) to enact several reforms in regards to military reorganisation and colonial administration. [6]

Sagasta’s attempts to force through his legislative agenda were frustrated by both the upper house and his government’s small and fractious majority. Having failed to pass legislation on social welfare and faced with the prospect that the left of his party would rebel and ally with the opposition in voting against Moret’s proposed budget, pre-empted the collapse of his government by resigning and asking the young king to dissolve the Cortes for the first time in his reign.

As he left the royal residence he reflected wryly it probably would not be the last.

BRIEF NOTES

[1] Moret had gradually built a power base amongst the rightist faction of the Liberals and had emerged as a threat to Sagasta’s hold over the party. His appointment as Finance Minister was largely viewed as a sop to the rightists at the expense of the party’s left and exposed the depths of the party’s factionalism.

[2] Moret famously criticised the general reliance on public works as a way to solve financial crises, stating in a parliamentary debate that “to construct railways where there is no trade is like giving a spoon to a man who has nothing to eat.”

[3] This included a refusal to grant Muslim troops the same religious status as their Christian counterparts, while both pay and promotion prospects remained low. The general lack of officers who spoke the same language as their troops also hindered relations.

[4] La Madrid had been one of the first native Filipinos to advance to a high rank amongst the officer corps and was widely respected within the colonial establishment as a man of action.

[5] While De La Torre’s earlier reforms had aimed to restrict the practice it as widely used in the often-brutal colonial wars that scarred the archipelago during the period.

[6] The reforms included increased pay for local troops and the granting of equal religious rights to Muslim and Buddhist soldiers. The civil service and colonial bureaucracy were opened up to the local population resulting in an increased Filipino middle class within the colonial cities.

Hey everyone,

I spoke a little rashly when I said I was aiming for weekly updates largely since I've recently started a new project based job which consumes a great deal of my time and efforts. However thank you all for patience and I should have something updated here (and some other projects in the pipeline) by either tomorrow or Sunday. Also thanks all for either nominating this or voting for it in the Turtledoves which was a profoundly humbling surprise for myself, and I'm glad people are enjoying this as much as I am writing it.

Regards,

morbidteaparty (o alternativamente fiesta del té morboso)

I spoke a little rashly when I said I was aiming for weekly updates largely since I've recently started a new project based job which consumes a great deal of my time and efforts. However thank you all for patience and I should have something updated here (and some other projects in the pipeline) by either tomorrow or Sunday. Also thanks all for either nominating this or voting for it in the Turtledoves which was a profoundly humbling surprise for myself, and I'm glad people are enjoying this as much as I am writing it.

Regards,

morbidteaparty (o alternativamente fiesta del té morboso)

Felipe VI and no he's an adult and reigning freely at this point.So what's the name of the new king and what's he Like?

Is he under a regent ?

Felipe VI and no he's an adult and reigning freely at this point.

Isn't that the same name as the current King of Spain?

Why has the name come back into fashion earlier ITTL? Or is it just luck and happenstance?

Threadmarks

View all 24 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The Eagle and the Bull: The Americas and Spain, 1884-1885 A Surprising Spirit of Radicalism: The Second Cánovas Ministry and Initial Domestic Policy, 1884-1885 Both of the Centre and the Periphery, 1884-86 Scandal, Sedition and Strife: The Collapse of the Cánovas Ministry Turbulence and Turmoil, 1887 The King is Dead, Long Live the King 1887-88 A Year of Lead: Colonial Pogroms and Metropole Repression, 1888 The Return to Stability: The Evergreen Cánovas, 1888

Share: