Chase, a financial expert, could be tapped later as Secretary of Treasury once Simon Cameron is out - Cameron would not last long due to his corruption, just like IOTL as War Secretary. In addition, Cameron actually preferred staying home so that he could maintain his grip over his Pennsylvania political machine.I take it Chase won’t be in Seward’s cabinet if he wins. I’m curious to see how the Democrats take the Seward nomination.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A House Divided Against Itself: An 1860 Election Timeline

- Thread starter TheRockofChickamauga

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 67 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

XLVIII: March on Managua XLIX: The Road to Groveton XLX: The Groveton Races Groveton Order of Battles Maps for the Battle of Groveton XLXI: Once More Unto The Breach, Dear Friends, Once More Map for the Battle of Warrenton XLXII: Their Souls Are Rolling On!Maybe we are presuming a bit too much that the Republicans will win. It might not be so in TTL!

Chase as an Independent candidate? EDIT - I mean, maybe he will do it just out of spite.

Last edited:

All very good points, but as will soon become clear, the 1860 election ITTL will transpire very different from the OTL one.At worst, Seward would only lose California (4 electoral votes), Oregon (3), Illinois (11), and the four electoral votes Lincoln got in New Jersey (Lincoln won these states with close margins IOTL) - which would not be enough to deny him an Electoral College majority.

Seward would carry New York, since he had home state advantage there and he was rather popular among immigrants as well - his pro-immigration stance if any would help him in New York. Also, IOTL, Lincoln beat a Fusion ticket with 7.4 points in NY IOTL, and back in 1856 NY also went for Fremont. The Reps also won NY in 1858 as well.

As for Pennsylvania, the Democratic Party there was already wrecked in 1858 elections.

So, the issue here would be Indiana, but IOTL Lincoln also carried the state with over 8 points.

After that bitter nomination, Seward certainly has no place in mind for Chase within his cabinet. The Democrats, meanwhile, still have to nominate their own candidate, and let's just say their convention might be described as even more divided and contentious than the Republican one (or maybe not, depending on how you view it).I take it Chase won’t be in Seward’s cabinet if he wins. I’m curious to see how the Democrats take the Seward nomination.

He could, but that requires a magnanimous leader who is willing to look past previous slights, strife, and conflict and instead focus on the greater good. Seward does not exactly fit that mold.Chase, a financial expert, could be tapped later as Secretary of Treasury once Simon Cameron is out - Cameron would not last long due to his corruption, just like IOTL as War Secretary. In addition, Cameron actually preferred staying home so that he could maintain his grip over his Pennsylvania political machine.

Always a possibility, especially considered that this TL's election is going to be more fractious than the OTL (if that is even possible!)Maybe we are presuming a bit too much that the Republicans will win. It might not be so in TTL!

Chase as an Independent candidate? EDIT - I mean, maybe he will do it just out of spite.

They are going to have issues all their own, as they are certainly sitting on a powder keg with their convention.Can't wait to see what the Democrats are up to!

Last edited:

III: The New Democratic Party

III: The New Democratic Party

Formerly the unstoppable force of American national politics, the once tightly unified fabric of the Democratic Party had begun to fray. Never before had they had to undergo this experience. Unlike their recently vanquished Whig rivals, ideology and political stances had never really served to divide the party. On occasion, conflicts between certain figures had produced this effect, most notable between Jackson and Calhoun in 1832 and Lewis Cass and Martin Van Buren in 1848, but those had been temporary and rapidly resolved when one figure stood triumphant over the other and party coherence was restored. By 1860, however, a new Democratic Party was being birthed, and there were certainly pains in the process. Previously, the Northern wing of the Democratic Party had been headed up by the so-called "Doughfaces", or men pliable to the will of their Southern constituents. One such man was James Buchanan, and another was the permanent chair of the convention, former attorney general Caleb Cushing.

By 1860, however, the Doughfaces began to dwindle within the Democratic Party, and a new faction arose, replacing them throughout their previous bastion of the North. Led by Stephen A. Douglas, they refused to be bullied into meek submission by their Southern compatriots, instead demanding their voice by heard by the party. Ultimately, their revolt and rupture with the Southern half of the party had occurred when the Lecompton Constitution had been brought to a vote before Congress. The constitution, drafted by a pro-slavery convention in the Kansas Territory, petitioned for entry into the Union with slavery being allowed to remain in Kansas. Backed by President Buchanan, the bill was expected to easily pass in the Senate. Standing in opposition, however, was Douglas, who promised to "resist it to the last." as he believed the elections had been fraudulent and popular sovereignty not properly enacted. Ultimately, he would rally his followers to side with the Republicans, despite the fact that the Republican motivation of free soil stood juxtaposed against his support of popular sovereignty. Even together, however, the two forces were unable to prevent its passage, if only barely. He had delayed it enough, however, for a new anti-slavery legislature to be elected in Kansas, who promptly withdrew the Lecompton Constitution and submitted a new one that ensured Kansas would become a free state. Despite not having strong feelings one way or the other on whether slavery was allowed in Kansas, the more radical Southerners in the nation quickly branded Douglas' stand against the Lecompton Constitution as proof that he was a closet abolitionist and secretly conniving with the Republicans, even though most knew the allegations to be false.

In his stand, Douglas, who to many prior had seemed a likely shoo-in for the 1860 presidential nomination, had undercut his candidacy. While he remained generally popular within the Northern wing of the party, he had earned the ire of both Buchanan and the radical Southerners, whose combined influence could likely deny him the nomination he so desired. Combined with a close run Senate re-election campaign in 1858, and Douglas was seeming to be a less and less viable candidate for a unified Democratic Party to rally around.

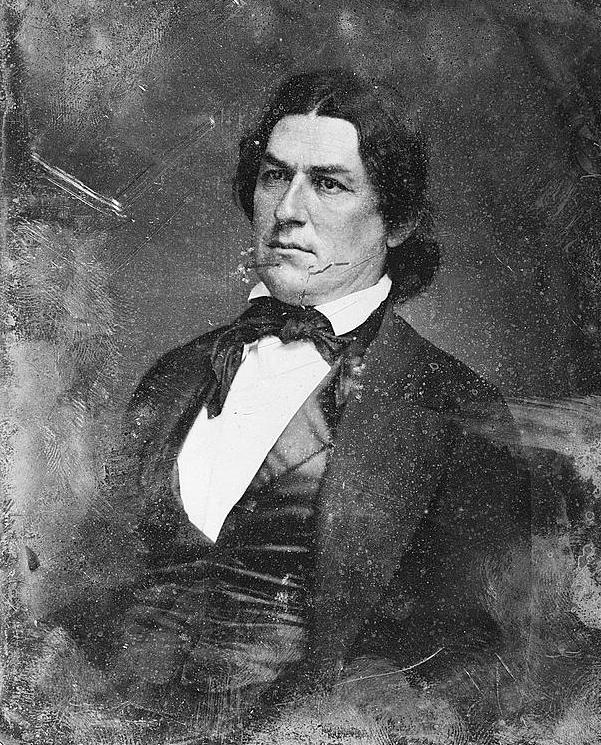

Senator Stephen A. Douglas, a man of passion, principles, and probable Democratic division

Douglas' two primary opponents at the convention would prove to be former House Speaker and current Virginia Senator Robert M.T. Hunter and Former Secretary of the Treasury James Guthrie. Although by no means a Fire-Eater in the vein of William L. Yancey, Hunter was certainly the candidate of the South, or at least what remained represented of it following a walk out of the delegates representing Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. A former Whig, Hunter switched to the Democratic Party in 1844 when he perceived a shift within the tone of the Whigs, which he believed was threatening slavery as an institution and its expansion into the West. Since then, he had rapidly climbed the Democratic party ranks and was currently seated in the Senate, where he had defended slavery, promoted the Lecompton Constitution, and made a name for himself for being a generally capable and skilled politician. With the absence of the Deep South to back a rabid Fire-Eater, Hunter was a solid choice by the remaining Southerners, if one almost certainly doomed to defeat by the walkout of the Deep South delegations. Despite this, he held a firm grasp over remaining Southern delegates.

Hoping to strike a middle tone between Douglas and Hunter was Guthrie. Having served with distinction as Secretary of the Treasury, he had also managed to avoid miring himself in the struggles and strife of sectional politics since then by staying out of national politics. Seen by supporters as a return to traditional Jacksonism and the age where slavery was not tearing the country asunder, he had an appeal to both Northerners and Southerners, which he was hoping would work to his advantage in a deadlocked convention. Rounding out of the field of minor candidates, alongside Dickinson would be Oregon Senator Joseph Lane--a Doughface--, and Tennessee Senator Andrew Johnson--a moderate like Guthrie.

Douglas' primary rivals for the nomination: Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, Robert M.T. Hunter of Virginia, and James Guthrie of Kentucky

The issue of reaching this count was only made even more unachievable when Chairman Cushing ruled that two-thirds total had to include the Southern delegates who had walked out of the convention, bringing the number of necessary delegates up from 169 to 202. When word of this reached Douglas' camp, which was currently in the midst of negotiations with Guthrie's, it blasted a gaping hole in their plan. Now, even if Douglas could convince Guthrie to endorse him, which now seemed less of a possibility with Guthrie getting cold feet from the rule clarification (or change, according to some), their totaled delegates would not reach the necessary 202, and certainly Hunter, Dickinson, and Lane could not be convinced to drop out in favor of the despised Douglas.

And so the endless balloting continued, with all realizing that realistically no one was going to be nominated. Nevertheless, the Democrats hopelessly persevered, with Cushing stubbornly refusing to acknowledge the need to change the delegate count to reflect the walkout of the Fire-Eaters. And thus, nothing was decided. In the end, after the 60th ballot, Cushing called for an adjournment of the convention, which was to reconvene in Baltimore 7 weeks later. By the time this was called, everyone's temper were fried, and even the promise of a break seemed unlikely to smooth over the now deeply sown and proven differences within the Democratic Party, now permanently fractured, at least until some conclusion on the slavery issue could be reached (which seemed impossible in the current circumstances). Douglas' men and the northern stalwarts had come to despise Guthrie's, Dickinson's, and Lane's camp from blocking their rightful nomination of their hero, and the Southerners, both the moderates under Hunter and the Fire-Eaters, had come to perceive the convention as rigged in the favor of Douglas, as proved, they believed, by the fact that he had consistently led on every ballot with well over a hundred more delegates than the runner-up, Hunter.

When the time had come for the next convention in Baltimore, it was clear that the Democratic Party was no longer a single entity. Instead, it had broken up into the followers of Douglas, who had tired of catering to the whims of the South, and the followers of the South, including the Doughfaces, who were increasingly turning to secession as the only way to protect their way of life.

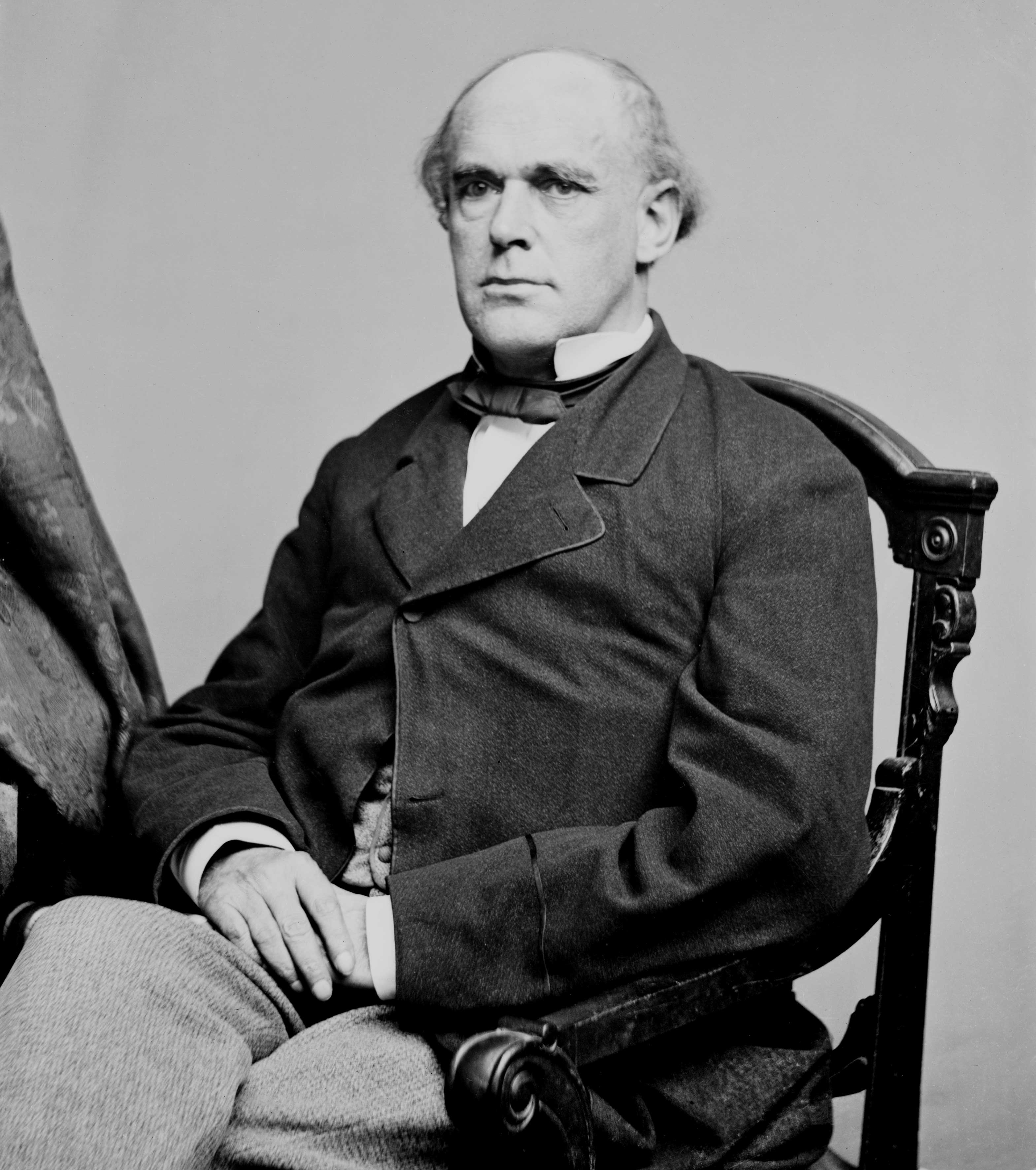

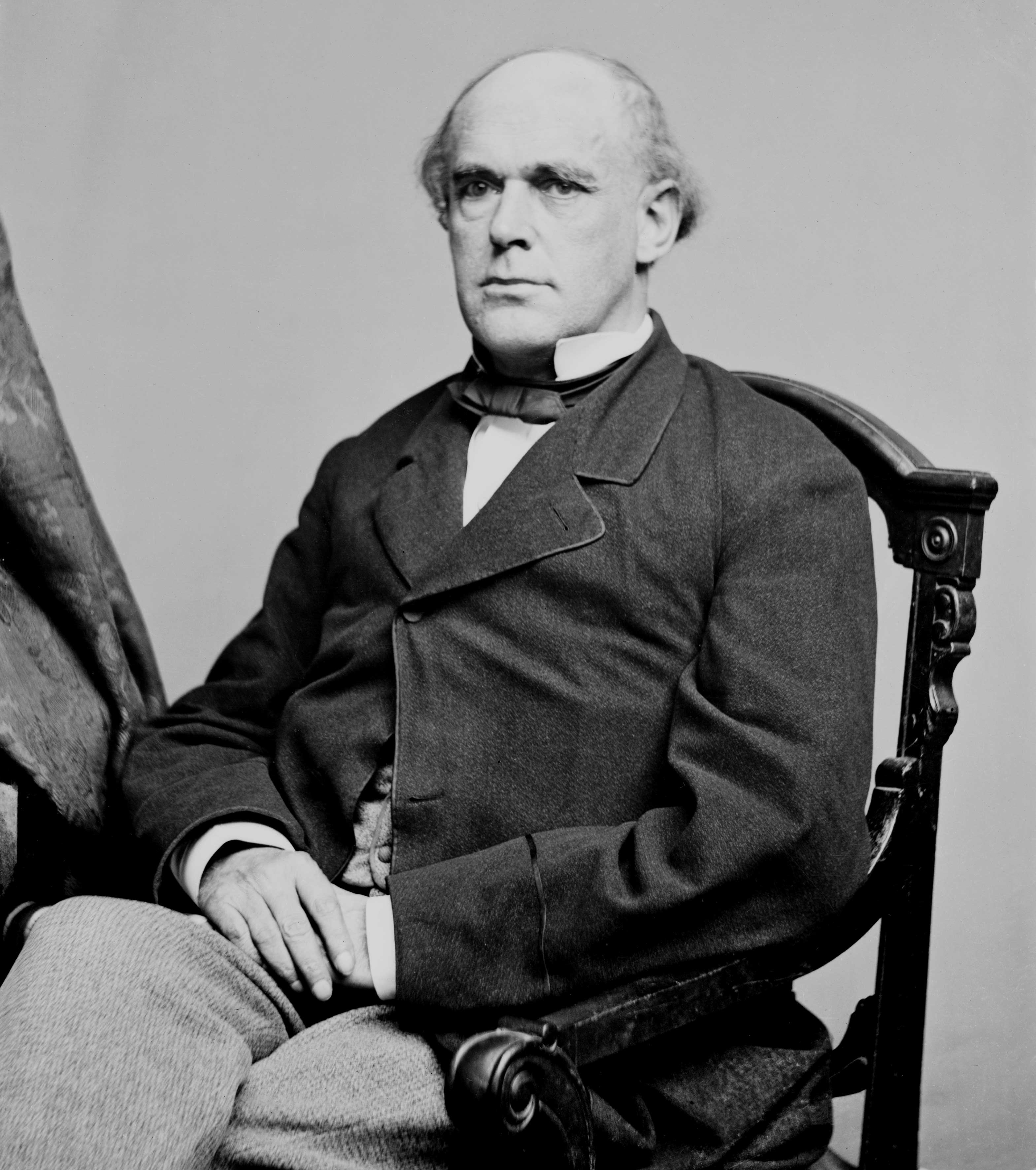

Caleb Cushing, the man who would unintently destroy the Democratic Party.

Last edited:

And I thought the Republicans were screwed in TTL.

Nice chapter! Now wondering what will happen in 7 weeks in Baltimore...

Nice chapter! Now wondering what will happen in 7 weeks in Baltimore...

Let's just say that both of OTL's major political party is going down a worst path ITTL.And I thought the Republicans were screwed in TTL.

Nice chapter! Now wondering what will happen in 7 weeks in Baltimore...

I sense a Constitutional Union victory coming on.Let's just say that both of OTL's major political parties are going down a worse path ITTL.

Well, John Bell might be able to get moderate Democrats to throw the House to him, though the Republicans wouldn't be happy with itI sense a Constitutional Union victory coming on.

I sense a Constitutional Union victory coming on.

Who says John Bell is going to be the Constitutional Union candidate? Although I'll admit it is going to be someone similar to him.Well, John Bell might be able to get moderate Democrats to throw the House to him, though the Republicans wouldn't be happy with it

So Crittenden agrees to run, then.Who says John Bell is going to be the Constitutional Union candidate? Although I'll admit it is going to be someone similar to him.

My apologies if I have missed this in the posts so far, but what exactly is the PoD for this TL? It has to be something well before the conventions themselves, such that Lincoln and Breckenridge (and possibly others) do not or cannot run.

There isn't one exact P.O.D. for this TL. If I had to pinpoint something, then I would just say that Lincoln is less ambitious than IOTL, so he doesn't position himself to receive the nomination and do his backroom dealings. Overall, though, this TL is focusing more on several different things going differently with some connection to each other rather than a domino trail where the P.O.D. creates all the differences (if that makes sense).My apologies if I have missed this in the posts so far, but what exactly is the PoD for this TL? It has to be something well before the conventions themselves, such that Lincoln and Breckenridge (and possibly others) do not or cannot run.

(Also love your profile picture and username. Always appreciate another George H. Thomas fan, and am I correct your username is in reference to Chickamauga?)

Maybe a Sam Houston candidacy ?There isn't one exact P.O.D. for this TL. If I had to pinpoint something, then I would just say that Lincoln is less ambitious than IOTL, so he doesn't position himself to receive the nomination and do his backroom dealings. Overall, though, this TL is focusing more on several different things going differently with some connection to each other rather than a domino trail where the P.O.D. creates all the differences (if that makes sense).

(Also love your profile picture and username. Always appreciate another George H. Thomas fan, and am I correct your username is in reference to Chickamauga?)

Fair enough then. Those types of starting points can lead to far more diverse scenarios than sticking to a single PoD, and I do look forward to where you are going with this.There isn't one exact P.O.D. for this TL. If I had to pinpoint something, then I would just say that Lincoln is less ambitious than IOTL, so he doesn't position himself to receive the nomination and do his backroom dealings. Overall, though, this TL is focusing more on several different things going differently with some connection to each other rather than a domino trail where the P.O.D. creates all the differences (if that makes sense).

(Also love your profile picture and username. Always appreciate another George H. Thomas fan, and am I correct your username is in reference to Chickamauga?)

A hundred times over yes, my (recently changed) username refers to Chickamauga and extends the homage to Thomas. Anything to help correct the injustice of him being the most unknown, unacclaimed, and unappreciated Civil War figure (relative to his overall rank) (and with this site being something of an exception) at the expense of Grant and especially Sherman.

Sam Houston will make an appearance soon.Maybe a Sam Houston candidacy ?

Glad to have found another Thomasite on this site! I do hope you can enjoy my TL!A hundred times over yes, my (recently changed) username refers to Chickamauga and extends the homage to Thomas. Anything to help correct the injustice of him being the most unknown, unacclaimed, and unappreciated Civil War figure (relative to his overall rank) (and with this site being something of an exception) at the expense of Grant and especially Sherman.

IV: Return and Revenge

IV: Return and Revenge

Despondent and devastated over his defeat at the Republican National Convention, and enraged by Seward's camp not directly reaching out to him to voice his opinion in the selection of a running-mate, Chase began brooding on his next move. Although he had fully expected to become the Republican presidential nominee, he had kept a back up plan in the back of his mind should he fail to be nominated. Feeling slighted by the party, and egged on by his ever ambitious daughter Kate, Salmon P. Chase decided to implement that plan. Since the 1840 election, a very minor party known as the Liberty Party had been running candidates for the presidency, although their candidates had never received more than 2.3% of the vote nationwide. Soon after their rise to some prominence in the 1844 presidential election, other parties had arisen, most notably the Free-Soil Party, and had taken key portions of the platform and the corresponding voter base. Despite their sudden fall from the limelight, they still managed to hold together somewhat, and had plans to gather in Syracuse, New York to nominate a candidate for the presidency.

Seeing them as a good starting base for his bid, Chase announced that he would be seeking to win the presidency by being nominated by the Liberty Party. Officially, however, he still remained affiliated with the Republican Party. He would encourage others to do likewise, claiming (accurately) that the Republican Party had no intent on forcing an end to slavery in the South in the near future, and that a new party had to rise to fight for abolition. His call was heeded by few Republicans within the national government, with only three representatives (Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, Owen Lovejoy of Illinois, and Martin F. Conway of Kansas) and three senators (John P. Hale of New Hampshire, Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, and Jacob Collamer of Vermont) joining him in his exodus to the Liberty Party.

Despite the relatively small number of incumbents Chase's revolt brought with him, plenty of others outside of government were eager to come, as they had nothing to lose. Among their number were former Indiana representative George W. Julian, former New York representative Horace Greeley, former Kentucky state representative Cassius M. Clay, and former mayor of Portland Neal S. Dow--who had made an almost national name for himself by passing the first prohibition law in a major city during his tenure. Greeting them would be a shocked former New York representative named Gerrit Smith, who was the perennial candidate for the Liberty Party and was fully expecting another nomination. Eager for the influx of support, but also privately bitter when it soon became revealed no one was serious considering him for the presidential nomination or even vice-presidential nomination now, he decided to accept the temporary chairmanship of the convention, hoping to be brought back into national politics back by backing a successful bid by a major politician.

Gerrit Smith, temporary chairman of the convention and key figure within the Liberty Party

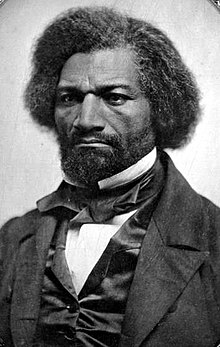

A look at the delegate rolls for the convention would reveal a surprising mix of men, including those even not traditional associated with electoral politics. Among their number, besides the previously mentioned ones, would be Frederick Douglass, the former slave turned voice of the abolitionist movement. Interestingly, he had already been part of the convention before Chase swept in with his cohorts. Well-known and popular with abolitionists, Chase was glad for him to be there, and even tried earn his favor by seeing to it that he was nominated for the chairmanship of the Rules Committee. Also present was Henry W. Beecher, who had made himself one of America's best known citizens abroad with his erudite sermons and firm stance for abolition. Even Walt Whitman, of poetic fame, served as a delegate from New York, as he had earlier done with the Free-Soil Party.

Perhaps most surprising, however, was that all six members of the so-called "John Brown's Secret Six" would also serve as delegates, with Thomas W. Higginson, Samuel G. Howe, Theodore Parker, Franklin B. Sanborn, and George L. Stearns all representing Massachusetts, and Gerrit Smith of course representing New York. A potential crisis relating to them arose when word arrived at the convention that federal marshals were riding for Syracuse to arrest Sanborn for his involvement with John Brown. Acting quickly, Smith saw to it that he was quietly spirited off to Canada to lay low until tempers fell and the matter passed. Most of the delegates present tried all they could to aid in the effort, providing Sanford with well over a hundred dollars before he escaped. Chase, however, was irritated that his plans had been disrupted, and made sure to hasten Sanford out the door so official duties could resume.

The delegates to the Liberty Party National Convention--which included the above-pictured Douglass, Whitman, Higginson, Beecher, and Dow--came from a variety of backgrounds and lived diverse lifestyles

Finally having received a nomination for the presidency, Chase turned to selecting a running-mate. Being himself a former Whig, Chase hoped Hale, at one time a Democrat before switching his affiliation to various opposition parties (including at one point the Liberty Party), would agree to run with him. Hale, who himself had run for president with the Free-Soil Party in 1852, declined the offer, fearing that being Chase's running-mate might permanently severe him from the Republican Party, in which he held much sway. Charles Sumner would similarly turn him down, claiming to prefer legislative to executive work. Finally, the last incumbent senator present at the convention, Jacob Collamer, would agree to the offer. Collamer had solid credentials as a politician, having served as a senator from 1855 and before that having been Postmaster General under Zachary Taylor and a United States Representative for Vermont. Altogether, Chase and the Liberty Party presented as strong of a ticket as they could have hoped for considering the circumstances. With his bid, Chase seemed likely to make the Republicans as divided, if not even more so, than the Democratic Party.

Salmon P. Chase and Jacob Collamer, candidates of the Liberty Party

Last edited:

The plot thickens. My hat off to you sir. Totally loving this timeline.IV: Return and RevengeDespondent and devastated over his defeat at the Republican National Convention, and enraged by Seward's camp not directly reaching out to him to voice his opinion in the selection of a running-mate, Chase began brooding on his next move. Although he had fully expected to become the Republican presidential nominee, he had kept a back up plan in the back of his mind should he fail to be nominated. Feeling slighted by the party, and egged on by his ever ambitious daughter Kate, Salmon P. Chase decided to implement that plan. Since the 1840 election, a very minor party known as the Liberty Party had been running candidates for the presidency, although their candidates had never received more than 2.3% of the vote nationwide. Soon after their rise to some prominence in the 1844 presidential election, other parties had arisen, most notably the Free-Soil Party, and had taken key portions of the platform and the corresponding voter base. Despite their sudden fall from the limelight, they still managed to hold together somewhat, and had plans to gather in Syracuse, New York to nominate a candidate for the presidency.

View attachment 638543

Seeing them as a good starting base for his bid, Chase announced that he would be seeking to win the presidency by being nominated by the Liberty Party. Officially, however, he still remained affiliated with the Republican Party. He would encourage others to do likewise, claiming (accurately) that the Republican Party had no intent on forcing an end to slavery in the South in the near future, and that a new party had to rise to fight for abolition. His call was heeded by few Republicans within the national government, with only three representatives (Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, Owen Lovejoy of Illinois, and Martin F. Conway of Kansas) and three senators (John P. Hale of New Hampshire, Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, and Jacob Collamer of Vermont) joining him in his exodus to the Liberty Party.

Despite the relatively small number of incumbents Chase's revolt brought with him, plenty of others outside of government were eager to come, as they had nothing to lose. Among their number were former Indiana representative George W. Julian, former New York representative Horace Greeley, former Kentucky state representative Cassius M. Clay, and former mayor of Portland Neal S. Dow--who had made an almost national name for himself by passing the first prohibition law in a major city during his tenure. Greeting them would be a shocked former New York representative named Gerrit Smith, who was the perennial candidate for the Liberty Party and was fully expecting another nomination. Eager for the influx of support, but also privately bitter when it soon became revealed no one was serious considering him for the presidential nomination or even vice-presidential nomination now, he decided to accept the temporary chairmanship of the convention, hoping to be brought back into national politics back by backing a successful bid by a major politician.

View attachment 638546With the convention now in his hands, Chase began orchestrating his nomination. For permanent chairman, John P. Hale was selected. A respectable choice and a man who would provide legitimacy to the proceedings, Chase would eagerly ensured his position. It also surely helped that Hale and Chase had a good working relationship from their time in the Senate together. Smith was perturbed, and even according to some, by being overlooked by the party he had held together almost entirely by his own force of will, but he would ultimately once again hold his peace for the good of the party.

Gerrit Smith, temporary chairman of the convention and key figure within the Liberty Party

A look at the delegate rolls for the convention would reveal a surprising mix of men, including those even not traditional associated with electoral politics. Among their number, besides the previously mentioned ones, would be Frederick Douglass, the former slave turned voice of the abolitionist movement. Interestingly, he had already been part of the convention before Chase swept in with his cohorts. Well-known and popular with abolitionists, Chase was glad for him to be there, and even tried earn his favor by seeing to it that he was nominated for the chairmanship of the Rules Committee. Also present was Henry W. Beecher, who had made himself one of America's best known citizens abroad with his erudite sermons and firm stance for abolition. Even Walt Whitman, of poetic fame, served as a delegate from New York, as he had earlier done with the Free-Soil Party.

Perhaps most surprising, however, was that all six members of the so-called "John Brown's Secret Six" would also serve as delegates, with Thomas W. Higginson, Samuel G. Howe, Theodore Parker, Franklin B. Sanford, and George L. Stearns all representing Massachusetts, and Gerrit Smith of course representing New York. A potential crisis relating to them arose when word arrived at the convention that federal marshals were riding for Syracuse to arrest Sanford for his involvement with John Brown. Acting quickly, Smith saw to it that he was quietly spirited off to Canada to lay low until tempers fell and the matter passed. Most of the delegates present tried all they could to aid in the effort, providing Sanford with well over a hundred dollars before he escaped. Chase, however, was irritated that his plans had been disrupted, and made sure to hasten Sanford out the door so official duties could resume.

With the crisis behind him, Chase once again set the gears in motion for his nomination. When the call came for presidential nominations, he would be the only one nominated, and he was almost unanimously chosen on the first ballot. Two delegates from New York, forgotten to history, would cast their votes for Smith, much to the chagrin of Chase. On the second ballot to make his nomination unanimous, unanimity was achieved, which somewhat assuaged Chase's pride. especially when he remembered that the same luxury had been denied to Seward by his stubborn refusal to release his delegates.

View attachment 638550

View attachment 638550

The delegates to the Liberty Party National Convention--which included the above-pictured Douglass, Whitman, Higginson, Beecher, and Dow--came from a variety of backgrounds and lived diverse lifestyles

Finally having received a nomination for the presidency, Chase turned to selecting a running-mate. Being himself a former Whig, Chase hoped Hale, at one time a Democrat before switching his affiliation to various opposition parties (including at one point the Liberty Party), would agree to run with him. Hale, who himself had run for president with the Free-Soil Party in 1852, declined the offer, fearing that being Chase's running-mate might permanently severe him from the Republican Party, in which he held much sway. Charles Sumner would similarly turn him down, claiming to prefer legislative to executive work. Finally, the last incumbent senator present at the convention, Jacob Collamer, would agree to the offer. Collamer had solid credentials as a politician, having served as a senator from 1855 and before that having been Postmaster General under Zachary Taylor and a United States Representative for Vermont. Altogether, Chase and the Liberty Party presented as strong of a ticket as they could have hoped for considering the circumstances. With his bid, Chase seemed likely to make the Republicans as divided, if not even more so, than the Democratic Party.

Salmon P. Chase and Jacob Collamer, candidates of the Liberty Party

Threadmarks

View all 67 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

XLVIII: March on Managua XLIX: The Road to Groveton XLX: The Groveton Races Groveton Order of Battles Maps for the Battle of Groveton XLXI: Once More Unto The Breach, Dear Friends, Once More Map for the Battle of Warrenton XLXII: Their Souls Are Rolling On!

Share: