38. Domestic Affairs. #2. Life at peace

38. Domestic Affairs. #2. Life at peace

RIP - the end of the 1st constitutional experiment

Just in an unlikely case that somebody still remember or cares about Catherine’s first major attempt to do something good for her subjects, the Codification Commission officially never was closed. It just was slowly dying from an exhaustion. The heated arguments never produced anything and a task of codifying the existing Russian laws never moved from the level zero. From five meetings per week it went to four, then to seven per month, then, officially, to two per week, then, due to the war (many of the members were on active army duty and happy to exchange the meetings to something more exciting and not requiring the boring things like thinking and reading ), the general commission was temporarily put on hold (its meetings were postponed first until May 1, then until August 1 and November 1, 1772, and finally until February 1, 1773) and never resurrected. Agony of the special commissions lasted longer but they also died not producing any noticeable results. The only end product were the honorary titles granted to Catherine at the opening.

Well, it was definitely fun while it lasted and the lesson learned was that for doing something productive you need small committees of 3 - 5 people. But this discovery Catherine kept to herself.

The domestic affairs

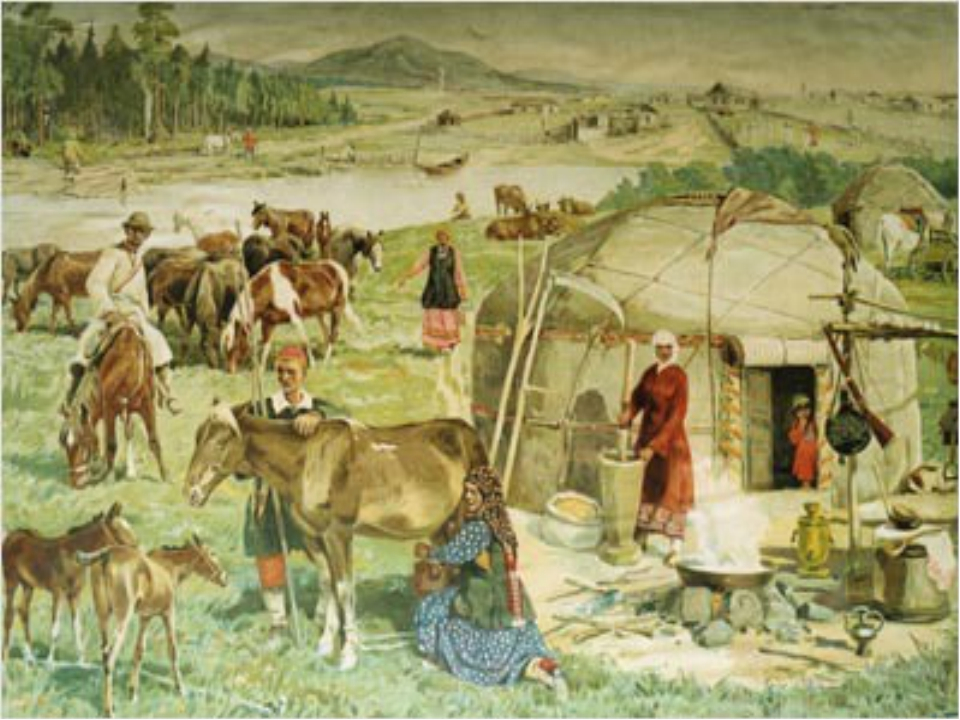

Above is the administrative map of the Russian Empire before the Ottoman War and Partition. It was created by Peter I and survived into 1770s with the minimal changes. As you can see, to the East of the Volga and Yaik (Ural) Rivers there were few huge gubernias which, due to their sizes combined with the rudimentary communications, were pretty much unmanageable. Which was extremely unfortunate both because at least some of them started playing increasingly important role in the Russian economy and because situation on a map did not quite reflected situation on a ground.

“It’s economy, stupid”

Obviously, Tsardom and then Empire needed a foreign trade. Initially, it was the only source of the precious metals [1] and then, with nomenclature of the imports expanding, the volume and nomenclature of the exports had to grow. Fortunately, the state was well positioned on that account having something that the outsiders with the money not just wanted but could not live without.

Traditionally, Russia, had virtually a natural monopoly of hemp [2] and flax and retained this position as long as sailing ships navigated the world's oceans [3]. England was totally dependent on Russian flax and Russian hemp, taking more than two-thirds of Russia's hemp exports and half its flax exports. More than 75% of England's flax imports was coming from Russia, and so, as a rule, did 97-98% of its hemp imports. The greater part of all the flax and hemp moving through the Sound in the eighteenth century was coming from Riga, that traditional emporium for Russian flax and hemp, and partly from St Petersburg. The lesser but still very important traditional export items also were related to the naval needs, tallow, leather, timber; in these products Russia had a competition but a consumption market still had been big enough for all Baltic (plus Norway) producers.

But in the 1720s a new important export item kicked in, increasingly squeezing a traditional main producer, Sweden. It was iron. Bar-iron production recorded by the Russian Council of Mines was 6,200 tons in 1722, 14,100 tons in 1736-38 and 21,800 tons in 1750. Then followed a rapid increase to 37,200 tons in 1760, 52,200 tons in 1770. In 1773 export of bar iron from St.Petersburg was 41,900 tons and between 55 and 75% were going to England.

Of course, in terms of value, Russian bar iron represented about 10% of the total value of Russian exports, i.e. less than one quarter of the value of hemp and flax products.

Intermission. To get a general picture, of total Russian exports, England was taking between three-quarters and four-fifths of the iron, nine-tenths of the timber products, two-thirds of the flax and hemp, and four-fifths of the tallow. England's share of St. Petersburg's exports was nine-tenths of the iron, between two-thirds and three-quarters of the tallow, and between three-quarters and four-fifths of the flax and hemp. Grain formed only 8 per cent of Russia's total exports and so far it was mostly rye.

So, as an export item, iron was still remote third to flax and hemp but with a share steadily growing. For the domestic purposes it was extremely important, taking into an account the growing needs of the Army and Navy. Civilian consumption remained quite low.

On the map above the main metallurgical plants in the European part of the empire are shown as the black squares [3]. Understandably missing are metallurgical plants in Baikal area producing silver and led. Anyway, it is obvious that the great concentration of these plants was in the Ural region. It is also obvious that, due to the importance of that region the government was paying a growing attention to it, which was a mixed blessing, taking into an account that “attention” and “competence” are not the synonyms.

All enterprises, state and private, were under jurisdiction of the Berg Collegium, which was giving permissions to open the new plants, allocating territories for them (accessibility of the water sources and forests was critical), and collecting all needed statistics about their production for the taxation purposes.

“Unhappy, unhappy, very, very, very unhappy!”

Bashkirs (Башкиры), being the biggest local ethnic group, had been the most squeezed one. Their initial habitat was the whole region between the Kama and Yaik (Ural) rivers and it was a bad luck that at least its northern part became the center of the Ural mining and metallurgical industry.

The plants had been built on their lands, which were either bought or just grabbed and later the peasants of the private plants often tried a land grab of their own. There were regulations and some purchases were officially acknowledged as illegal but the process kept going on because, among other considerations, the metallurgy was run on a charcoal and needed a lot of wood. There already were few uprisings earlier in the century and the minor “adjustments” were not solving the fundamental need of a final clear definition of the territorial issues and Bashkirs’s social status within the Empire.

To be fair, while considering the plants and the people related to them as a major evil, some of the Bashkirs started adopting to the new situation, even going into the mining business by collecting the copper ore from the surface deposits, selling it to the plants and getting the officially confirmed mining rights.

Yaik (Ural) Cossacks lived in the region between the Bashkirs on the North and Caspian Sea (and Kalmyks) on the South, mostly along the Yaik River with the Kazakh Minor Juz on the other side of it.

With the exception of the Zaporizhian Cossacks, they were considered the least disciplined and obedient to the central power with the said power rarely missing a chance to screw things up even more. Since the 1720s they were under jurisdiction of the Military Collegium and if before Catherine it was mostly let them be, Zaakhar Chernyshov decided that this is a wrong attitude. Election of the local commanders-administrators were replaced with the appointments, which was the general practice, but, this being a relatively small and not critically important host, he let the local (appointed) leadership to run the show without any serious oversight.

The additional twist had been added by Catherine when she established state monopoly on the salt. On the second map you can see a small empty square slightly to the left from the lower Volga. It is Baskunchak lake, one of the major places of the salt extraction.

For the Yaik Cossaks, who lived by fishing and selling the salted fish, the resulting increase of the salt’s cost was a serious hit on a pocket made even more serious because their leaders were buying from the state distribution rights thus adding more to the already raised price. Besides, by the uncontrollable appointments of their relatives to the previously elective position, they were also managing to squeeze the ordinary cossacks from the best fishing areas.

Then, there were coming the minor lapses from Military Collegium, which were adding to the irritation. For example, the state was supplying the host with the lead and gunpowder but, in his zeal to achieve uniformity, Chernyshov ordered to send them the ready cartridges, which would make sense for the troops with the uniform firearms but not those who had them of all imaginable calibers and systems. Then there was a rumor that the Cossacks sent to the fighting army are going to have their beards saved. True or not, it caused a loud uproar among the Old Believers amounting to a big part of the host.

All complaints to the Collegium were, so far, ignored and Catherine was provided with a picture of an unruly mob disrespecting her authority, which produced a predictable reaction.

Management of the plants

The state plants had been run by the managers who, most often, had been the mining or metallurgy specialists combining professional and administrative activities. Their ranks within Berg Collegium were not incorporated into the Table of the Ranks leaving them in a social limbo, which made this service unattractive to the noble class and most of them belonged to the taxable classes. Typically, they did not possess any land assets and had to exist on their salary so, as a result there was a tendency to pass position from father to son as a guarantee of family’s income and quite understandable attempts to squeeze some “extras” to augment their salaries.

For the state plants there were strict regulations regarding use of the work force, which were routinely violated causing regular problems warranting direct involvement of the government ending up, quite often, with the dismissal of the local administrators. So, basically, administration on that level had been squeezed between their superiors and the workers (for whom they were enemies #1) while, their job was very complicated and not too rewarding socially or financial.

Workers of the state plants were state peasants, aka personally free people who were, however, under obligation to perform certain amount of work for the state. Each state plant had villages assigned to it by Berg Collegium, often without too much attention being paid to the trifles like distances. With the low-skilled labor force being on something like rotation or simply allowed to get back to home for ploughing and harvesting seasons, these people sometimes had to travel hundreds versts in one direction.

Their pay was not too bad. For example, an apprentice was getting 12 rubles per year (3 1/3 kopeck daily), skilled worker - 18 (5 kopecks) and master - 30 (8 1/3 kopecks). In a daily purchasing power in Ekaterinburg it meant, correspondingly, 10 - 12, 16 - 20, 27 - 32 kilograms of rye. But it also involved the working day of 11 - 15 hours, depending upon a season. Officially, there were 248 working (for the state) days per year with the breaks for the religious holidays and 20 days for “vacations” to attend to their households.

Needless to say that there were numerous fines cutting into the official income and administration always could cheat the illiterate workers in other ways so, regardless their attitudes toward specific administrator, they tended to see the office with its books as the evil incarnate.

The surroundings were not too friendly and quite often the plants had been built as the fortresses with their own artillery. On a lower level, the Bashkir raids of the villages were rather routine and so were the clashes over the land.

Workers of the private plants were the serfs with no rights whatsoever and their only advantage was that they tended to live close to the plant. However, the mandatory religious and other holidays were enforced and the owners were not interested in their workers dying from starvation so there were allowances for the agricultural work.

Local Government. A need to keep the huge areas under control was not well backed by the administrative structure. The governors resided far away from the potentially troublesome areas living too much to the local low level officials or garrison commanders who did not have in their possession too much in the terms of enforcement. Most of the military force available in the peripheral gubernias were the small garrison units of the border forts. These garrisons usually were packed with the elderly or handicapped officers and soldiers or the officers sent there as a punishment. For the communication purposes each of them had a small Cossack unit and the Cossacks considered this a burdensome duty from which the rich ones tended to buy themselves out.

Basically, this was a dead end career-wise, the living conditions and supplies were not too good and the forts were holding mostly due to a fear of the retribution, or just inadequate military skills of the potential assailants rather than their real military value.

A governor had in his disposal some higher quality troops but not too much and in the case of something serious would need an outside help. As with the garrisons, a great importance was in prestige and advantages of the “regularity” over “irregularity”. Also, it was convenient to have numerous hating each other groups ready to help in suppressing rebellions of their enemies. But if these groups managed to get together, there would be a big trouble.

What will get first, the problem or the reform, was anybody’s guess.

______

[1] In a complete absence of the domestic sources of gold and silver, Tsardom was buying the silver thalers, melting them, making something like a silver wire out of which the tiny sliver kopecks had been cut. The bigger foreign silver and gold coins had been used as the state awards.

[2] Tempting as it is to insinuate, no, the Brits needed it not as a recreational drug but for the ropes and cables used by their navy. Weren’t they rather weird and boring even then? Missing such a great chance to have a happy nation.

[3] This environmentally-friendly wind-powered transportation was being destroyed by the greedy Anglo-Saxons. 😢

[4] I don’t think that this is in any way related to Malevich or that he got inspiration from a similar map. It is just that the good ideas may come to many people independently.

“Business is a combination of war and sport.”

“A friendship founded on business is better than a business founded on friendship.”

“Good business is business with profits for both sides.”

Various authors

“…During Tamerlane times, one Don Cossack named Vasily Gugnya, with 30 Cossack comrades and one Tatar, withdrew from the Don for robbery to the east. He made boats, went to the Caspian Sea, reached the mouth of Yaik and, finding its surroundings uninhabited, settled in them.”

P.A.Rychkov, recorded legend regarding foundation of the Yaik Cossack recorded in 1748

“… Where would he find those cossack criminals, order to torture, execute and hang them.”

Ivan IV (the Terrible), order to voyevoda Ivan Murashkin, 1577

“Possession of the Yaik River, with its rivers and tributaries, and with all the lands on the right and left sides, from the confluence of the Ileka River to the mouth.”

Tsar Michail Fedorovich Romanov, territorial grant to the Yaik Cossacks, 1615

“Let your name be known to the important people.”

Chinese curse.

“A friendship founded on business is better than a business founded on friendship.”

“Good business is business with profits for both sides.”

Various authors

“…During Tamerlane times, one Don Cossack named Vasily Gugnya, with 30 Cossack comrades and one Tatar, withdrew from the Don for robbery to the east. He made boats, went to the Caspian Sea, reached the mouth of Yaik and, finding its surroundings uninhabited, settled in them.”

P.A.Rychkov, recorded legend regarding foundation of the Yaik Cossack recorded in 1748

“… Where would he find those cossack criminals, order to torture, execute and hang them.”

Ivan IV (the Terrible), order to voyevoda Ivan Murashkin, 1577

“Possession of the Yaik River, with its rivers and tributaries, and with all the lands on the right and left sides, from the confluence of the Ileka River to the mouth.”

Tsar Michail Fedorovich Romanov, territorial grant to the Yaik Cossacks, 1615

“Let your name be known to the important people.”

Chinese curse.

RIP - the end of the 1st constitutional experiment

Just in an unlikely case that somebody still remember or cares about Catherine’s first major attempt to do something good for her subjects, the Codification Commission officially never was closed. It just was slowly dying from an exhaustion. The heated arguments never produced anything and a task of codifying the existing Russian laws never moved from the level zero. From five meetings per week it went to four, then to seven per month, then, officially, to two per week, then, due to the war (many of the members were on active army duty and happy to exchange the meetings to something more exciting and not requiring the boring things like thinking and reading ), the general commission was temporarily put on hold (its meetings were postponed first until May 1, then until August 1 and November 1, 1772, and finally until February 1, 1773) and never resurrected. Agony of the special commissions lasted longer but they also died not producing any noticeable results. The only end product were the honorary titles granted to Catherine at the opening.

Well, it was definitely fun while it lasted and the lesson learned was that for doing something productive you need small committees of 3 - 5 people. But this discovery Catherine kept to herself.

The domestic affairs

Above is the administrative map of the Russian Empire before the Ottoman War and Partition. It was created by Peter I and survived into 1770s with the minimal changes. As you can see, to the East of the Volga and Yaik (Ural) Rivers there were few huge gubernias which, due to their sizes combined with the rudimentary communications, were pretty much unmanageable. Which was extremely unfortunate both because at least some of them started playing increasingly important role in the Russian economy and because situation on a map did not quite reflected situation on a ground.

“It’s economy, stupid”

Obviously, Tsardom and then Empire needed a foreign trade. Initially, it was the only source of the precious metals [1] and then, with nomenclature of the imports expanding, the volume and nomenclature of the exports had to grow. Fortunately, the state was well positioned on that account having something that the outsiders with the money not just wanted but could not live without.

Traditionally, Russia, had virtually a natural monopoly of hemp [2] and flax and retained this position as long as sailing ships navigated the world's oceans [3]. England was totally dependent on Russian flax and Russian hemp, taking more than two-thirds of Russia's hemp exports and half its flax exports. More than 75% of England's flax imports was coming from Russia, and so, as a rule, did 97-98% of its hemp imports. The greater part of all the flax and hemp moving through the Sound in the eighteenth century was coming from Riga, that traditional emporium for Russian flax and hemp, and partly from St Petersburg. The lesser but still very important traditional export items also were related to the naval needs, tallow, leather, timber; in these products Russia had a competition but a consumption market still had been big enough for all Baltic (plus Norway) producers.

But in the 1720s a new important export item kicked in, increasingly squeezing a traditional main producer, Sweden. It was iron. Bar-iron production recorded by the Russian Council of Mines was 6,200 tons in 1722, 14,100 tons in 1736-38 and 21,800 tons in 1750. Then followed a rapid increase to 37,200 tons in 1760, 52,200 tons in 1770. In 1773 export of bar iron from St.Petersburg was 41,900 tons and between 55 and 75% were going to England.

Of course, in terms of value, Russian bar iron represented about 10% of the total value of Russian exports, i.e. less than one quarter of the value of hemp and flax products.

Intermission. To get a general picture, of total Russian exports, England was taking between three-quarters and four-fifths of the iron, nine-tenths of the timber products, two-thirds of the flax and hemp, and four-fifths of the tallow. England's share of St. Petersburg's exports was nine-tenths of the iron, between two-thirds and three-quarters of the tallow, and between three-quarters and four-fifths of the flax and hemp. Grain formed only 8 per cent of Russia's total exports and so far it was mostly rye.

So, as an export item, iron was still remote third to flax and hemp but with a share steadily growing. For the domestic purposes it was extremely important, taking into an account the growing needs of the Army and Navy. Civilian consumption remained quite low.

On the map above the main metallurgical plants in the European part of the empire are shown as the black squares [3]. Understandably missing are metallurgical plants in Baikal area producing silver and led. Anyway, it is obvious that the great concentration of these plants was in the Ural region. It is also obvious that, due to the importance of that region the government was paying a growing attention to it, which was a mixed blessing, taking into an account that “attention” and “competence” are not the synonyms.

All enterprises, state and private, were under jurisdiction of the Berg Collegium, which was giving permissions to open the new plants, allocating territories for them (accessibility of the water sources and forests was critical), and collecting all needed statistics about their production for the taxation purposes.

“Unhappy, unhappy, very, very, very unhappy!”

Bashkirs (Башкиры), being the biggest local ethnic group, had been the most squeezed one. Their initial habitat was the whole region between the Kama and Yaik (Ural) rivers and it was a bad luck that at least its northern part became the center of the Ural mining and metallurgical industry.

The plants had been built on their lands, which were either bought or just grabbed and later the peasants of the private plants often tried a land grab of their own. There were regulations and some purchases were officially acknowledged as illegal but the process kept going on because, among other considerations, the metallurgy was run on a charcoal and needed a lot of wood. There already were few uprisings earlier in the century and the minor “adjustments” were not solving the fundamental need of a final clear definition of the territorial issues and Bashkirs’s social status within the Empire.

To be fair, while considering the plants and the people related to them as a major evil, some of the Bashkirs started adopting to the new situation, even going into the mining business by collecting the copper ore from the surface deposits, selling it to the plants and getting the officially confirmed mining rights.

Yaik (Ural) Cossacks lived in the region between the Bashkirs on the North and Caspian Sea (and Kalmyks) on the South, mostly along the Yaik River with the Kazakh Minor Juz on the other side of it.

With the exception of the Zaporizhian Cossacks, they were considered the least disciplined and obedient to the central power with the said power rarely missing a chance to screw things up even more. Since the 1720s they were under jurisdiction of the Military Collegium and if before Catherine it was mostly let them be, Zaakhar Chernyshov decided that this is a wrong attitude. Election of the local commanders-administrators were replaced with the appointments, which was the general practice, but, this being a relatively small and not critically important host, he let the local (appointed) leadership to run the show without any serious oversight.

The additional twist had been added by Catherine when she established state monopoly on the salt. On the second map you can see a small empty square slightly to the left from the lower Volga. It is Baskunchak lake, one of the major places of the salt extraction.

For the Yaik Cossaks, who lived by fishing and selling the salted fish, the resulting increase of the salt’s cost was a serious hit on a pocket made even more serious because their leaders were buying from the state distribution rights thus adding more to the already raised price. Besides, by the uncontrollable appointments of their relatives to the previously elective position, they were also managing to squeeze the ordinary cossacks from the best fishing areas.

Then, there were coming the minor lapses from Military Collegium, which were adding to the irritation. For example, the state was supplying the host with the lead and gunpowder but, in his zeal to achieve uniformity, Chernyshov ordered to send them the ready cartridges, which would make sense for the troops with the uniform firearms but not those who had them of all imaginable calibers and systems. Then there was a rumor that the Cossacks sent to the fighting army are going to have their beards saved. True or not, it caused a loud uproar among the Old Believers amounting to a big part of the host.

All complaints to the Collegium were, so far, ignored and Catherine was provided with a picture of an unruly mob disrespecting her authority, which produced a predictable reaction.

Management of the plants

The state plants had been run by the managers who, most often, had been the mining or metallurgy specialists combining professional and administrative activities. Their ranks within Berg Collegium were not incorporated into the Table of the Ranks leaving them in a social limbo, which made this service unattractive to the noble class and most of them belonged to the taxable classes. Typically, they did not possess any land assets and had to exist on their salary so, as a result there was a tendency to pass position from father to son as a guarantee of family’s income and quite understandable attempts to squeeze some “extras” to augment their salaries.

For the state plants there were strict regulations regarding use of the work force, which were routinely violated causing regular problems warranting direct involvement of the government ending up, quite often, with the dismissal of the local administrators. So, basically, administration on that level had been squeezed between their superiors and the workers (for whom they were enemies #1) while, their job was very complicated and not too rewarding socially or financial.

Workers of the state plants were state peasants, aka personally free people who were, however, under obligation to perform certain amount of work for the state. Each state plant had villages assigned to it by Berg Collegium, often without too much attention being paid to the trifles like distances. With the low-skilled labor force being on something like rotation or simply allowed to get back to home for ploughing and harvesting seasons, these people sometimes had to travel hundreds versts in one direction.

Their pay was not too bad. For example, an apprentice was getting 12 rubles per year (3 1/3 kopeck daily), skilled worker - 18 (5 kopecks) and master - 30 (8 1/3 kopecks). In a daily purchasing power in Ekaterinburg it meant, correspondingly, 10 - 12, 16 - 20, 27 - 32 kilograms of rye. But it also involved the working day of 11 - 15 hours, depending upon a season. Officially, there were 248 working (for the state) days per year with the breaks for the religious holidays and 20 days for “vacations” to attend to their households.

Needless to say that there were numerous fines cutting into the official income and administration always could cheat the illiterate workers in other ways so, regardless their attitudes toward specific administrator, they tended to see the office with its books as the evil incarnate.

The surroundings were not too friendly and quite often the plants had been built as the fortresses with their own artillery. On a lower level, the Bashkir raids of the villages were rather routine and so were the clashes over the land.

Workers of the private plants were the serfs with no rights whatsoever and their only advantage was that they tended to live close to the plant. However, the mandatory religious and other holidays were enforced and the owners were not interested in their workers dying from starvation so there were allowances for the agricultural work.

Local Government. A need to keep the huge areas under control was not well backed by the administrative structure. The governors resided far away from the potentially troublesome areas living too much to the local low level officials or garrison commanders who did not have in their possession too much in the terms of enforcement. Most of the military force available in the peripheral gubernias were the small garrison units of the border forts. These garrisons usually were packed with the elderly or handicapped officers and soldiers or the officers sent there as a punishment. For the communication purposes each of them had a small Cossack unit and the Cossacks considered this a burdensome duty from which the rich ones tended to buy themselves out.

Basically, this was a dead end career-wise, the living conditions and supplies were not too good and the forts were holding mostly due to a fear of the retribution, or just inadequate military skills of the potential assailants rather than their real military value.

A governor had in his disposal some higher quality troops but not too much and in the case of something serious would need an outside help. As with the garrisons, a great importance was in prestige and advantages of the “regularity” over “irregularity”. Also, it was convenient to have numerous hating each other groups ready to help in suppressing rebellions of their enemies. But if these groups managed to get together, there would be a big trouble.

What will get first, the problem or the reform, was anybody’s guess.

______

[1] In a complete absence of the domestic sources of gold and silver, Tsardom was buying the silver thalers, melting them, making something like a silver wire out of which the tiny sliver kopecks had been cut. The bigger foreign silver and gold coins had been used as the state awards.

[2] Tempting as it is to insinuate, no, the Brits needed it not as a recreational drug but for the ropes and cables used by their navy. Weren’t they rather weird and boring even then? Missing such a great chance to have a happy nation.

[3] This environmentally-friendly wind-powered transportation was being destroyed by the greedy Anglo-Saxons. 😢

[4] I don’t think that this is in any way related to Malevich or that he got inspiration from a similar map. It is just that the good ideas may come to many people independently.