You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dream of the Poison King: A History of the Pontic Empire

- Thread starter Nassirisimo

- Start date

Well, the historical record doesn't really mention how Laodice exits the scene, but rest assured I have a fitting end planned for her.

It's a shame you've been so busy, because that would have made a perfect Mother's Day update.

Thanks!This is great!!

More of it will be coming. I should have a lot more free time for at least a month after next week so I intend to work on the TL more.Well written and looking forward for more of this TL!

You know, the thought never crossed my mind, but that would have been brilliant. Though if you're anything like me, you'll probably have a rather sick taste from how Laodice meets her end.It's a shame you've been so busy, because that would have made a perfect Mother's Day update.

Sinope, 415 AC

Those who followed Mithradates to Sinope were met with a scene of enormous celebration as the young king entered the city. From the rooftops, people cheered his name as he and his army made their way through the streets. All the people of the city and the villages near it had crowded the route to the royal palace hoping to catch a glimpse of their new ruler, whose exploits in Pontus and beyond had already gained him a larger-than life reputation. And for those who had not seen before, he was not a disappointment. Murmurs among the crowd compared him to a young Alexander, albeit one with black rather than blonde hair. His friends who had fled Sinope with him so many years ago rode alongside him, and had now developed reputations of their own.

It had been five years since the group had last seen Sinope, but it may have well have been a life time. The streets had changed little, though the city itself did not seem so impressive after they had seen many of the cities of Persia and Babylonia. A million things ran through Mithradates’ mind as he approached the palace. How many of the people he had known growing up were still there? He thought of how to react if his mother was waiting for him, or indeed if Rescuturme was still there. He felt as if his stomach was knotting as he wondered if his mother took her frustration out on poor Rescuturme. All would be resolved when he reached the palace it seemed.

As the palace of the Pontic king came into sight, Mithradates thought that it did not seem as large as it did when he was a child. Nevertheless, unlike the palaces he had visited in the East, this was unquestionably his. He had finally arrived at his proper station in life, and he made a quiet vow to himself never to be subservient to anyone else again. As he and his army approached the palace, he saw a man dragging a woman out the doors of the palace. He recognized the man as Holophernes, the commander of the palace guard. The woman was none other than his own mother, Laodice. It appeared that she hadn’t had the opportunity to flee Pontus yet.

Holophernes shouted out to Mithradates. “My king! We have apprehended your treacherous snake of a mother, and have the other rebels in our custody”

Finishing his sentence, he threw Laodice at the feet of Mithradates. After taking a second to pick herself up from the dust, Laodice looked at Mithradates with something that he had never seen before in her. The look of fear. For all her plotting to achieve power and luxury, she was now powerless and covered in dust at the feet of the son she had tried to kill many lives. Her fate would not be decided at this moment though. Mithradates commanded Holophernes to take her to the dungeon with the rest of the rebels. For now, celebrations were in order.

The festivities were extravagant, but Mithradates felt rather out of place for much of it. Part of this was that he felt used to living rough with friends rather than making small talk with the potentates of Sinope. In ordinary circumstances he enjoyed attending a symposium but with his mother in prison and a number of other questions left unanswered, he could not enjoy himself. Halfway through the event, he made his excuses and left, making his way to the harem. When he arrived at the doors, he said a single word to the guard at the doors. “Rescuturme?”

The guard shook his head with a pained look in his eye.

“How did it happen?”

“Not long ago sire. I think she had hoped to use her as a pawn when you were marching your army toward Sinope. When it became apparent that you would not negotiate, your mother flew into a rage that I had never seen before. One would not think it from a woman like her but she smashed furniture and cursed the Gods. Then a break came in the rage and we’d all hoped that she had calmed down. But she turned toward us with a glimmer of madness in her eye, and told us to bring Rescuturme. We refused, so she simply got one of those Galatian dogs to do her dirty work. To his credit, he did not make her death a painful one, but all the same…”

Mithradates nodded, devastated at the news but unwilling to betray the deep sadness and loss that he felt inside him. No, if he was going to express his emotions, it would have to be through the medium of revenge. With this thought, he made his way to the dungeon of the palace. Kleon was there, as was his mother and a number of courtiers who had unambiguously sided with them. This was not the mother that he knew as a child. The calculating look in her eyes had been replaced with a maddened fear, as if she had not adapted well to her changed circumstances.

“So, come to gloat in your triumph my son? I do not want your mercy and I shall expect none”

Her tone was almost self-pitying, and Mithradates would have none of it. “I can expect your hostility to me as a block on your road to power, but why did you have to hurt her?”

“That mad Dacian bitch? She only desired the same thing, but through you my son. I couldn’t let the little bitch have her reward…”

With that, Mithradates struck Laodice so fiercely that the sound of a couple of her teeth falling on the floor could be heard. Blood started running from her mouth and she turned away from her son, whimpering. Mithradates grabbed her by the chin and turned towards her. “Rest assured, you will meet the same fate as Rescuturme, but you shall not do so in the same way. Your death will not be quick, it shall not be free of pain and it shall be remembered for as long as I live. That is the legacy that you will leave to this world” He left the dungeon which was almost entirely silent, save for the pained cries of his mother.

When it came to the method of death his mother would suffer, Mithradates harked back to hallowed antiquity, and used a method that had been employed in the days of the Achaemenids. When it came to her turn to be executed, a grim silence overtook all who watched it. His mother was stripped naked and placed in the trunk of a tree which had been hollowed out, with only her head, hands and feet protruding. Mithradates could see the attempt at a resolved look on her face, but could see the deep fear behind this. A slight smile came to his face.

After this, she was force fed milk and honey until she had developed a rather severe case of diarrhea. With this horrific show, most who were watching the execution left, and for many the event became a conveniently forgotten part of the new king’s rise to power. Laodice was covered in honey and left in a stagnant pond which attracted insects which began to live inside her. In the end, she took almost fourteen days to die, almost all of which was spent in complete agony as her flesh was corrupted while she still lived. For the Greeks of Sinope, this punishment represented the worst excesses of Persian barbarism, but for Mithradates, this was simply justice. [1]

******

Sarosh Shahzad; The Life and Times of Mithradates the Great (Awal Academy Press, 2459)

The First Years of Mithradates' Reign

Sarosh Shahzad; The Life and Times of Mithradates the Great (Awal Academy Press, 2459)

The First Years of Mithradates' Reign

Upon the conquest of Sinope, Mithradates began establishing the building blocks of his future Empire, and in doing this there had to be serious thought invested into what kind of Kingdom he was to rule. Immediately, he had two examples based on his predecessors and other rulers in history. Both his father and mother had pursued policies that were pro-Roman, even going so far as to aid Rome against the rebellion of Aristonicus in Pergamum. As a reward from this, Rome demanded territories which Pontus had been rewarded with after proving support, which Mithradates’ mother had acquiesced to. While Rome had proven to be a very capable power in defeating those opposed to her, Mithradates could see very little benefit in allying himself to Rome. It is probable that Mithradates was only a young teenager when he decided that Pontus would follow an independent foreign policy.

Mithradates instead looked to the examples of other great Empire builders such as Alexander the Great, and the Persian king Cyrus. Both had taken on the dominant powers of their day and conquered much of the world, though it was apparent to Mithradates that these achievements were not just built on the individual genius of these two. After all, hadn’t Hannibal been as great a genius and lost? It is likely that the official story of the Pontic chronicles that Mithradates first concentrated on building up the resources available to Pontus are telling the truth. Mithradates would concentrate on turning the Pontic army from a rag-tag levy into a world-class army, as well as expanding well outside the attention of Rome. This would be an easy task, as it would be less than a decade after Mithradates coming to the throne that Rome would be mortally threatened by the arrival of the Cimbri and Teutones.

The first few years of Mithradates reign were actually fairly quiet in terms of expansion and reform. Much of his time and effort were spent setting up his own court (which was radically different in terms of makeup from that of his predecessors) [2], as well as refilling the treasury that had been drained by his mother. Luckily, with major trade routes coming through Pontus in light of warfare to the south, this task was easier than it would have otherwise been. In addition to this, there is compelling evidence that Mithradates received something in the way of subsidies from the Parthian Kingdom, which may have been part of a strategy by Mithradates II of Parthia to build up buffers to Roman expansion east. The bad years of his mother were soon forgotten as Pontus once again became a prosperous kingdom. This started to endear the Greeks of the coast, many of whom depended on trade, to Mithradates as well, and stories of his able stewardship began to spread outside of Pontus.

With the finances of Pontus looking healthy once again, Mithradates could turn to the second part of building his power base, which was an effective army. Although he had won the Battle of Sinope, the king was well aware that the levies that won him his kingdom would not be adequate for battles outside of it. Many of the men had joined up out of personal choice rather than obligation, and they would be unlikely to be willing to fight far away from home. In addition to this, they were undisciplined and ill-equipped. Mercenaries had also proven that their loyalty on the battlefield could be limited in life-or-death situations, which filled Mithradates with some discomfort about relying on them as his predecessors had. Mithradates likely came to the conclusion that a professional army was needed only a few years into his reign, but this still left the question of what form such an army would take.

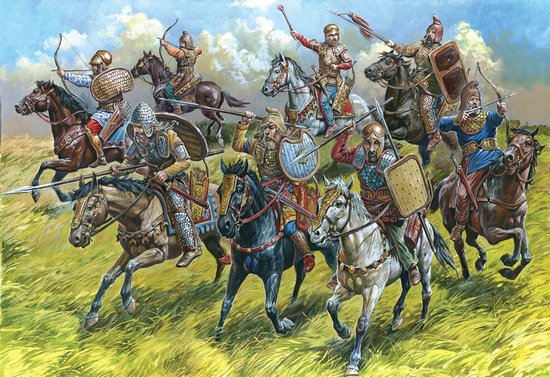

The Macedonian model of Pikemen in a phalanx formation supported by cavalry had been dominant in the centuries following Alexander, had been discredited a number of times in the past century. In battles such as Magnesia in the West and Ecbatana in the East, the rigid phalanxes of Alexander’s successors had been consistently defeated by more mobile forces, and this was a lesson that had not been lost on Mithradates [3]. Mithradates encouraged veterans from the Greek, Roman and Parthian worlds to advise him on creating a new army which he hoped would combine all the most useful features from each. To a large extent, he was successful. Although he did not create a force of cataphracts that both the Parthians and Armenians utilised, he formed Pontus’ nobles into a heavy cavalry force supplemented by horse archers from the steppes north of the Pontic Sea. His infantry were based partly on Roman legions, though later observers noted that Pontic infantry could not properly go toe to toe with Roman legions on equal footings, nor were they capable of the strategic mobility of the legions.

These two would be the base of the Pontic army, though these were not the only troops that Mithradates would use. In departure from his usual policy, Mithradates continued to hire archers from Crete as his predecessors had done, perhaps a testament to the excellent abilities of these troops. Mercenaries from Scythia and Sarmatia supplemented the cavalry of Pontus, and gave at least part of the Pontic army an unrivalled tactical mobility that would be useful in certain terrains. Mithradates was also the first Pontic monarch who appears to have seriously considered the navy as a force. Pontus was famous for its forests, and the Pontic navy built by Mithradates would be built with boxwood from the kingdom itself [4].

It was the building of a navy as much as anything that indicates that Mithradates’ “Pontic Sea Strategy” was not merely propaganda. The idea of turning the land surrounding the sea into united empire in which trade could take place would not only improve the prosperity of the Kingdom of Pontus, but ensure that a lot of new revenue would flow into the coffers of the Pontic Kingdom. In addition to this, much of the land surrounding the Pontic Sea was out of the notice of Rome, ensuring that Mithradates could expand there without making the Romans fear of his intentions. Pontic domination over areas like Cappadocia would not be pursued, and Mithradates would greatly increase the power of his Kingdom.

Even before Mithradates began his chain of conquests around the Black Sea, there is considerable evidence that he enacted deep economic reforms within Pontus. He improved infrastructure, making sure that more roads were paved and that banditry was combated. He removed various internal tariffs, which earned him the enmity of some provincial governors and nobles, but made him even more popular among townsfolk. However, his own personal popularity was able to offset much of the dissent that appeared among the ruling classes when these reforms were implemented. Thus Mithradates was able to encourage trade, weaken the power of the landed nobility in relation to himself and still keep the treasury full. The increase in prosperity seen in the first part of Mithradates’ rule was noted even by Roman travellers, who contrasted it with the increasing desolation seen in Roman Asia.

This is not to say that the increase in Pontus’ prosperity was down to Mithradates. In fact, the biggest single factor encouraging the movement of trade through Pontus was the fact that traditional routes in Mesopotamia and Syria were unsafe due to the on-off warfare that followed in the wake of Seleucid power. There appears to have been little awareness of this in Pontus, and an assumption that Pontus’ place as a trade hub was permanent. If history had gone differently and Pontus stayed a middle-sized kingdom, it would have almost certainly encountered fiscal crises later on in the 5th century as trade patterns shifted away from Pontus and toward more convenient routes in the South. As it was though, Mithradates’ policies would ensure that the wealth would flow through Pontus, and that it would fund the creation of a very powerful state.

Mithradates quietly bided his time and built his army for the first few years after he came to the Throne, and it was around four years after he entered Sinope that he received a request for help from the Greek cities of Taurica and the Bosporan Kingdom. They were under increasing pressure from Scythian chieftains, whose raids of Greek towns and villages became more and more frequent. Mithradates saw this as the golden opportunity he needed to gain glory from conquest, as well as to embark on his project of an Empire on the Pontic Sea. In the spring of 419, Mithradates and around 15,000 Pontic soldiers sailed north to be the saviours of the beleaguered Greeks of the Taurican Peninsula.

******

[1] - As far as I'm aware, the sources for Scaphism as a punishment come from Greek and Roman sources. Still, as Mithradates would have had knowledge of the punishment, I don't consider it too inaccurate for him to have picked on it as a fitting punishment. It isn't the way I'd like to die though...

[2] - In OTL, of around 80 important governors and commanders in Mithradates' court, around 4 or 5 of them had been in his father's regime. This represents a big change in terms of who's in charge.

[3] - The successor states had all been steadily evolving away from the simplistic phalanx + cavalry model of Alexander for centuries, and incorporating more mobile soldiers into their armies.

[4] - The navy would be so useful that it would be one of the concessions demanded by Sulla when drawing up his first truce with Mithradates in OTL.

What a way to go...wonder why the people at Netherrealm never thought of this...

So the objective is now to gain the Cimmerian Bosporus through their war with the Scythians? Should seem like a challenge, even more so since he doesn't go after the resources of Colchis first.

So the objective is now to gain the Cimmerian Bosporus through their war with the Scythians? Should seem like a challenge, even more so since he doesn't go after the resources of Colchis first.

[1] - As far as I'm aware, the sources for Scaphism as a punishment come from Greek and Roman sources.

On the other hand, the Greek sources typically attribute it to the Persians - one of the things that make me wonder whether the stories of scaphism might be three parts propaganda - and no doubt Mithridates will have heard of what Artaxerxes (allegedly) did to his namesake soldier in BC 401.

But... yeesh. No, that's not the way to go.

So after taking the Crimea. Mithradates marches round the Black Sea, up the Danube, across the Alps and attacks Italy. All the while recruiting mercenaries to his banner. The Roman Republic is destroyed in epic fashion.

guinazacity

Banned

Now this would be one hell of a mother's day update.

Great story nassir, i love to see you writing again hahah

Great story nassir, i love to see you writing again hahah

I hope it will one day be the equal of Crescent, but we will see.Great TL so far nassir! This looks like its going to be exciting

Also, holy shit! Thats not a pleasant way to die!i mean, Mithradates's mother may have been unlikable, but still, wow.

And yeah, it's a method of execution that makes stoning look like the height of civilized behavior in comparison.

Well, part of the reason I put it on was as the first sign of Mithradates' often brutal disregard for other people that he had in OTL as well as TTL. While there was certainly much to admire about him, one also has to keep in mind that his actions would make him one of the most "evil" people of the 20th century.Ouch, scaphism! Truly a brutal, brutal punishment, esp. for one's own (biological) mother.

Looking forward to more.

In OTL, Mithradates was actually able to conquer Taurica with very few men in comparison to his later campaigns. Part of this was just fudging of numbers, but another part of it may have been due to Parthian support. When I was doing my research for the TL, there was an article which put forward the viewpoint that Mithradates' resources were so impressive during the Mithradatic war because the Parthians had been funding his battle against the Romans. I think this as well as other question marks really throw into balance where Mithradates got much of his resources from.What a way to go...wonder why the people at Netherrealm never thought of this...

So the objective is now to gain the Cimmerian Bosporus through their war with the Scythians? Should seem like a challenge, even more so since he doesn't go after the resources of Colchis first.

The fact that (at least to my knowledge) only Greeks and Romans mention it leads me to think that part of it may be embellishment on the part of the Greeks to make the Persians look like cruel barbarians. That Mithradates would have heard about it from Greeks was my main consideration when deciding whether or not it would be an appropriate punishment. It's certainly a good way to showcase his cruelty to those who oppose and betray him though.On the other hand, the Greek sources typically attribute it to the Persians - one of the things that make me wonder whether the stories of scaphism might be three parts propaganda - and no doubt Mithridates will have heard of what Artaxerxes (allegedly) did to his namesake soldier in BC 401.

But... yeesh. No, that's not the way to go.

Well, he has started around about the same time he did in OTL, which was probably in his teenage years. It becomes a plot point a bit later on, so watch this space.So when does the poison King begin his mithridatic regime upon his body?

That was actually a plan of his later in life, after defeat in the Mithradatic wars. It didn't get very far as his son rebelled and forced Mithradates to commit suicide. Mithradates' aims in regards to Rome will likely be set in a few years, when on schedule with OTL, Mithradates is visited by a chap named Gaius Marius.So after taking the Crimea. Mithradates marches round the Black Sea, up the Danube, across the Alps and attacks Italy. All the while recruiting mercenaries to his banner. The Roman Republic is destroyed in epic fashion.

If it came with a tagline, I imagine it would be something like "Don't try and kill your kids mom. It pays off".Now this would be one hell of a mother's day update.

Great story nassir, i love to see you writing again hahah

Barita Drustan; The Most Important Campaigns of History (Bibracte Academy Press, 2310)

The Pontic Conquest of Taurica

When it took place at the time, the Pontic conquest of the Taurican peninsula was a rather insignificant event, and went little noticed by the wider world. In the two expanding empires of the world, Rome and China, the visit of the king Jugurtha and the conquest of Nanyue were the most significant events. The petty war of a petty king outside of Rome’s attention seemed even to bother the paranoid Romans little. However, the conquest of the Taurican peninsula by the later Mithradates the Great of Pontus was the first in a long line of wars that would see the balance of power in the Western half of Eurasia turned upside down. It was one of the most significant acquisitions of Mithradates before his war with the Romans and even at an early point in his reign dwarfed the achievements of his predecessors.

The campaign had its origins in the long-time woes of the Greek cities of the Taurican peninsula.Mithradates comes into the picture when the citizens of the Greek cities of Taurica, in theory ruled by a king from the Spartocid line, sent a request for aid to the king of Pontus [1]. They cited the increasing threat of Scythian raids to life and property, and the inability of their own king to face down the Scythian chieftains. Over previous centuries the Scythians on the peninsula had expanded their power at the expense of the Greeks in the Bosporan kingdom. Some cities decided to ally with the Scythians instead of their fellow Greeks, partly because unity in the face of danger was hardly a Greek virtue, but partly because the Scythians often left Greek cities in alliance with them alone. The breaking point for the Greeks came when Chersonesus was sacked by the Scythians. This drove the various heads of the Bosporan cities to send the aforementioned request to Mithradates.

Mithradates, who was planning an expedition to somewhere for a few years by this point, grasped the opportunity. He set sail from Sinope with around fifteen thousand of his own men. He and his army arrived at the capital of the Bosporan Kingdom, Panticapaeum. There, the people of the city welcomed his arrival as if he had been king. The actual king, holed up in his palace in a fit of depression, did not react when the people of the city declared Mithradates as their king and protector. His armies had not yet killed a single enemy combatant and he had already legitimized himself as the ruler of the Taurican peninsula.

Despite this, Mithradates wasted no time. His own force was well equipped and trained; though it lacked recent combat experience and rumours from the interior suggested that as many as a hundred thousand Scythian warriors were now operating in Taurica under the command of the Scythian king, Scilurus. This seems like an excessive number, though it was probably that Mithradates was seriously outnumbered by his foes on the peninsula. He began integrating the part-time militias the Greeks of Taurica had formed into his own army increasing his number by around five thousand. Cities which had been acting independently of the king in Panticapaeum now pledged their allegiance to Mithradates, on the condition that he took decisive action against the Scythians. The Pontic army would soon take to their task with gusto, attacking the weakened Scythians nearer to the Greek towns.

Many of these weakened Scythian bands had no answer to the light cavalry employed by Pontus, which was able to catch up to the Scythian horse archers and defeat them in and to hand combat. Eventually, this encouraged the Scythian king himself to bring his army in opposition of Mithradates. The Scythian army was larger, though Pontus had the advantages of training and organization, and the battle was a resounding victory for Pontus, with much of the Scythian army being scattered, and Scilurus himself being captured by Pontic forces. Mithradates had already cut the head off the Scythian serpent, and had gained a magnificent prize to parade around the Greek cities of Taurica in demonstration of his greatness. However, what should have been the end of the Scythian threat did not materialise as it.

From the ashes of Scilurus’ regime in Scythia, something new emerged. Historians name a new Scythian king named Mazaspar and note that he was a brilliant warrior. Many Scythians banded to him, seeing the new king as a strong challenge to the emerging Pontic order in the peninsula. However, other details about the nature of his rule are sparse on the ground, save for the desire to push Mithradates off of Taurica and restore the usual order of business there.

Needless to say, this conflicted with Mithradates’ goal of making the Taurican peninsula a part of his Black Sea Empire. If Mithradates was to achieve his aim, than Mazaspar would have to be defeated. In the campaign season of 420, Mithradates set out to catch Mazaspar and decisively defeat him. However, although the Scythians had begun to settle in the decades prior to the war, they still found it easy enough to abandon their settlements rather than fight against the odds. As they retreated, they pursued a “scorched earth” policy against Mithradates, hoping to weaken his army steadily by denying it supplies. Eventually, Mithradates was forced to give up the pursuit of Mazaspar by his starving armies. He would winter in Panticapaeum, marshal his resources, and set out against Mazaspar once again in 421.

This time, he managed to pin down the new Scythian king. Although the Scythian king attempted an encirclement of the Pontic army with his mobile cavalrymen, they once again found the Pontic cavalry an able foe, and Mazaspar’s army crumbled. Unlike with Scilurus though, there would be no enemy king captured to parade around the Greek towns of Taurica. Pontic records note Mazaspar as dying “manfully”, surrounded by Pontic dead. Mithradates treated the body with respect and allowed it to be buried with worldly goods, as per Scythian custom. As Mithradates had just vanquished the last serious resistance to him on the Taurican peninsula, he had room to be generous to his defeated enemies. Now even Scythian chiefs swore allegiance to Mithradates as king.

Originally, the cities of the Bosporan kingdom had sent a request to Mithradates in the hopes that he would be a saviour rather than a ruler. However, the thorough nature of his defeat of the Scythians ensured that he would simply be too powerful in the peninsula to have to take the wishes of the cities into consideration. Not only this, but he was now personally popular in many of these places, and for centuries later he would be known by the Bosporans as “Soter”, or saviour [2]. Mithradates would thus not leave with a simple alliance with the Greeks of Taurica. Instead it would become the first appendage of Mithradates’ Pontic Empire.

Mithradates actually took time to institute a relatively close form of control in Taurica. Cities would be provided a limited measure of autonomy, but most power would lie in a bureaucracy that was loyal to Pontus, and indeed was drawn mostly from cities such as Sinope and Amestris. Taurica would be governed by a man personally appointed by Mithradates, and would be replaced once every two years to prevent said governor from building a power-base in the area. This would allow Mithradates to make the most of the resources in the region without risking his authority. It kept the Scythians happy, who found employment in Mithradates’ armies rather than harassing the Greek cities, which in turn made the Greek population rather satisfied with the arrangement.

Thus Mithradates had managed to make the most of the opportunity which had presented itself three years earlier. His army was now battle hardened and had gained Scythian auxiliaries. The Greek cities of the Taurican peninsula grew in prosperity now that more resources could go into trade and production rather than fighting off the Scythian menace, and thus found the taxes paid to the King of Pontus to be a comparatively light burden. Mithradates had found a relatively easy solution that had increased his own power and kept all parties on the peninsula reasonably satisfied [3]. When it came to his future conquests, such uncomplicated and beneficial settlements would be elusive at best and impossible at worst, but the conquest of Taurica represented something of a game-changer in Pontic history. It gave the kingdom resources vastly superior to any other kingdom in Asia Minor, and would in time give Pontus the ability to challenge the greater powers of the Mediterranean basin. For this reason, Mithradates’ campaign in Taurica can deservedly be called a campaign of enormous importance.

******

[1] - The sources for the situation in Taurica are contradictory at best. Some point the way toward the Bosporan Kingdom still being an actual thing, others treat the Greek city states as separate entities. So I went for the boring middle road in representing them.

[2] - This dies out with cultural shifts that come in waaaay down the line. But we'll cross that bridge when we come to it.

[3] - Mithradates strikes it lucky here. Most of his subsequent conquests will bring just as many headaches as they solve, and much of the Pontic Empire really isn't going to look like the core regions. Again, more of this later.

And thus Mithridates is crowned King of the Cimmerian Bosporous.

Nice update, though I know for sure that control of the Black Sea would have to continue at the expense of other Black Sea states.

Nice update, though I know for sure that control of the Black Sea would have to continue at the expense of other Black Sea states.

Who are Mithridates' naval rivals at this point? His control over Taurica seems precarious if he doesn't have supremacy in the Black Sea.

Who are Mithridates' naval rivals at this point? His control over Taurica seems precarious if he doesn't have supremacy in the Black Sea.

Only groups I can think of is the Odrysian Kingdom and Colchis.

The Inevitable Mithradatid Caliphate will grow!Ooo Taurica

He will likely do this as he did OTL, incorporating Greek cities into his Empire and making non-Greek peoples submit to him. All of this will encourage trade along the coast, making Pontus richer and building his resources for the future wars he'll be involved in. However, it won't be as easy as the conquest of Taurica was.And thus Mithridates is crowned King of the Cimmerian Bosporous.

Nice update, though I know for sure that control of the Black Sea would have to continue at the expense of other Black Sea states.

Who are Mithridates' naval rivals at this point? His control over Taurica seems precarious if he doesn't have supremacy in the Black Sea.

These don't really present enough of a threat to be rivals to Mithradates. In OTL, the Pontic navy was actually stronger than the Roman navy in the First Mithradatic War. It isn't quite up to those levels yet but is unquestionably the strongest in the Pontus Euxine at this time. Not only does this enable Mithradates to strike anywhere on the coast that he wants, but helps combat piracy and encourage trade in the region. In contrast, the weak Roman naval presence in the Mediterrenean lead to pirates becoming so powerful that they were actually able to seize cities and hold them to ransom. At least until Pompey came along.Only groups I can think of is the Odrysian Kingdom and Colchis.

This is where Pontus' brilliant navy comes in useful. Troops can be ferried fairly easily, and Taurica is easily defendable anyway. As of the moment the area isn't too rich, but prosperity is artificially lowered by the long-standing unrest. It is likely that under Mithradates rule, provided he can keep it from being attacked, the place will become far richer. And again, the propaganda value of being seen as a defender of Hellenism is valuable too.Interesting that Mithridates went to Taurica... what does he have to gain there? A long march to defend, marginally prosperous subjects... I guess there's always prestige...

Sarosh Shahzad; The Life and Times of Mithradates the Great (Awal Academy Press, 2459)

Mithradates and his Coastal Empire

Mithradates and his Coastal Empire

The Pontic Sea Empire was very much the Empire that Mithradates had consciously aimed for since he ascended to the throne. The great historians of the pre-modern age often characterised the Empire he built later on as an accident, and there is some truth to this. The policies that he instituted in his territories surrounding the Pontic Sea suggest that he had a solid idea for what place these territories would take in his empire. He saw these areas as natural extensions of the Pontic Kingdom he inherited, ensuring that the king of Pontus would be the highest authority in the territories. Internal tariffs were all but non-existent to encourage trade, agriculture and urban life all flourished. If Mithradates had been in the mould of his forefathers, he might have been satisfied with Pontus and his addition of the Taurican peninsula, but he was significantly more ambitious than they had been.

The campaign in Taurica would be the last campaign Mithradates would personally be involved with for some time. Indeed, it was the most important conquest that Pontus made around the Pontic Sea, but it was followed with many more. Many Greek colonies that surrounded the Pontus Euxine proved quite happy to declare their loyalty to Mithradates, who allowed them significant internal autonomy. In return for taxes, they were virtually guaranteed a measure of freedom as well as protection from peoples such as the Sarmatians, Thracians and other “barbarian” peoples. However, many of these so-called barbarians were far less willing to swear fealty to the Pontic king, and a number of them mounted impressive resistance against his armies. [1]

However, in the end many of these native chieftains were forced out of Pontic territory, which by 422 had left Pontus the master of much of the coastline. Pontus grew rich as Sinope became a major center of trade. Silk, amber, grain and timber all flowed through it while being exported to places as far away as Rome. This made Pontic merchants notoriously wealthy, and gave Mithradates the epitaph of a second Croesus among those less enchanted with his rule. At a time when most surrounding lands were falling prey to various kinds of depredation, the prosperity of Pontus stood out as a heartening example. This would not go unnoticed by the inhabitants of other states in Anatolia, who began to view Mithradates as a possible deliverer from their own corrupt kings and Roman domination. [2]

It was at this time that Mithradates began perfecting his infamous propaganda machine. A number of influential and notoriously anti-Roman philosophers had made their home in Sinope, fleeing the Roman-dominated Greek mainland as well as the crumbling Diadochi kingdoms. The most famous of these was Metrodorus of Scepsis, commonly known as the “Rome Hater”. These, along with a number of his friends, helped craft the image that Mithradates wanted. This was an image of a fair and just king, appealing to both Persian and Greek alike, and willing to preserve the “old world” from the ravenous Roman wolf. Although hostilities between Mithradates and Rome were still many years away, even at this early point Mithradates portrayed himself as a king hostile to Rome. Thiswas rather untrue in the light of trading links between the two; it would help prepare the ground for future efforts.

It should be noted that it is unclear as to how much Mithradates saw himself as bridging the Hellenic and Persian worlds. Certainly, he seemed as eager to keep Greek company as Persian, and was reportedly a keen patron of Greek theatre. However, it is telling that his festivals tended to be held in the Persian rather than Greek manner, and that sacrifices to important Persian deities as well as Ahura Mazda are recorded far more than sacrifices at Greek temples. Perhaps most importantly, Mithradates had chosen to give all of his sons Persian rather than Greek names. Whether this was something conscious, or simple a window into Mithradates’ Persian internal identity is unclear, though may serve as an explanation for some of his later actions.

As well as the active propaganda campaign, Mithradates also aimed to improve his diplomatic position in the wider world. By now the growth of his kingdom had started to attract the attention of other monarchs, particularly his erstwhile protector Mithradates II of Parthia. Whatever enmity the men had harboured toward each other previously was set aside as the two recognized each other as useful. If Parthia could be persuaded not to threaten Pontus’ Eastern flank, Mithradates of Pontus could feel more secure in his efforts of empire-building. Similarly, Mithradates of Parthia saw Pontus as a potentially vital buffer between himself and the Romans. A number of important pacts were made between the two kings. Both would cooperate when it came to the Kingdom of Armenia, and agreed to the succession of the Prince Tigranes upon the death of the current Armenian king. Mithradates of Parthia also promised Mithradates secret monetary support in the event of a war with Rome. Both parties were satisfied with the treaties pulled up. [3]

By 431, Mithradates had comfortably established Pontus as the major middle power of the Mediterranean basin. The Kingdom was increasingly prosperous; the army had built up a wealth of experience at turning the Pontus Euxine into a Pontic lake. The Eastern flank was secured with the revival of close relations with Parthia and with the exception of Rome, and there were few powers that could present more than a minor irritation to Pontus. However, Rome was indeed a serious concern for Pontus. Roman politicians looked toward Pontus as a potential bonanza in terms of loot and taxes, which made Mithradates keen to build up anti-Roman sentiment in Pontus. With this background, it is rather astonishing that Mithradates received a most unusual visitor in 431. A man who came to his court with a significant retinue was none other than the legendary Roman General, Gaius Marius.

******

The Visit of Gaius Marius, Sinope, 431 AC

The Visit of Gaius Marius, Sinope, 431 AC

Sinope was already gaining a reputation even as far as the Western Mediterranean as being a hotbed of anti-Roman sedition. Perhaps this was the reason why the visit of the Roman general Marius was such a surprise to many in Pontus. Marius was renowned as a heroic general for his part in beating off an invasion of Germanic nomads a few years earlier. Not only had he saved Rome from doom, but he was the vanguard of reform within Rome’s army himself, moulding the Roman army into a professional one. [4]

On the face of it, his visit was a friendly one to visit a rising power and remind the king Mithradates of his family’s tradition of friendship with Rome. However, Marius and his friends in Rome had an ulterior motive in planning the trip. Partially, it was to be a not too subtle hint that Rome had noticed the expansion of Mithradates around the Pontus Euxine, and that any attempt to interfere with the status quo in Asia Minor would not be tolerated.

However, with this in mind he was still received with great civility from the Pontic court and Mithradates in general. He saw it as an important opportunity to know his future enemy as best as possible. And indeed, there was some curiosity surrounding Marius himself, the man who had saved Rome from immense peril at the hands of wandering barbarians. He enjoyed the Greek celebrations held to honour his arrival, and manage to ingratiate himself with those at the court who did not harbour anti-Roman sentiments. But even they could not deny the attractiveness of his personality. And Mithradates coolly observed the Roman. It was not until the last night of Marius’ visit that the two would discuss matters of any significance.

“I must confess” Mithradates tried as best he could to act slightly tipsy, giving the impression to Marius that he was letting his guard down. “I have always been most surprised at the rapid expansion of Rome. A city that comes out of nowhere in the space of a hundred years and turns the world upside down…”

“Success comes in a short time often, it is true. But it is the result of years of hard work. To use an example, Alexander’s great conquests were possible only through the army his father had built. Or indeed, Rome’s greatness has come only at the cost of centuries of struggle”

“Or through a magical property conferred by the She-wolf’s milk” Mithradates tried to offer a humorous explanation. It served only to wear away Marius’ mask and reveal the rather tired man underneath.

“That would not explain why we Italians have done so well though. Rome conquers us and a few generations, we are one of them. Except the Samnites I would guess, but even they will give up one day. This is why Rome cannot and will not be stopped, since she absorbs her enemies into herself, and if they will not submit, they will be wiped off the face of the world”

Mithradates’ thoughts turned to Carthage, Rome’s great rival in the Western Mediterranean. Despite the genius of the general Hannibal, Rome had ground Carthage to the ground and had utterly destroyed the city. “It would certainly be that way. It appears that only the Gauls have successfully stood against Rome and won”

Marius shook his head. “If indeed they have won. I would say that a long time in the future, maybe the Gauls of the lands beyond the Alps may find themselves ruled by us, like their cousins on our side of the Alps do now. As I said, Rome may be slow but in the end there are none who stand in her way forever”

Marius’ voice itself seemed to be stung by Rome’s resilience to challenge. He had never really considered himself to be an ally of the failed Gracchi though he was sometimes associated with them in the minds of others. No matter how hard he tried to break into the ranks of the political elites, he was disappointed. His military success had not afforded him political dominance as he had once hoped, and even now his erstwhile pupil Sulla was threatening to overshadow all he had accomplished.

Mithradates challenged Marius “Nothing in history lasts forever. Empires in Mesopotamia dominated the world until the people of Media and Persia rose against them, and they in turn were defeated by the Greeks. Rome may stand up to her challengers for now, but she will one day meet her match. Such is the way of things”

“I warn you Mithradates, that you are not Rome’s match. You are a formidable king, and are evidently going to rule well. But I tell you that Rome is mightier than you can imagine. If you choose to do battle with her, you will die on the run and broken as Hannibal did. Opposition to us may be a pleasing fantasy but the reality will shock you to be sure. I know the faults of Rome better than any man so believe me when I say that in the end, resistance is futile”

Mithradates was taken aback at the unfiltered nature of what Marius was saying, but he thought it appropriate to respond in kind. “So what would you have me do Marius? How would you advise me to deal with your countrymen?”

“The answer is simple Mithradates. You either make yourself stronger than the Romans, or obey them!” [5]

******

[1] - In OTL, Appian notes that Mithradates was defeated by a people named the "Achaeans" and their stratagem. What this stratagem is wasn't explained.

[2] - Some sources claim that Roman rule wasn't really much worse than the rule of native kings.

[3] - There is considerable evidence that Mithradates and Parthia cooperated this way in OTL. At least one historian notes Parthia as a possible source of funding for Mithradates' wars against Rome.

[4] - The image of Marius single-handedly changing the Roman Army isn't an unchallenged one, and I have seen it argued that he was really the culmination of decades of change.

[5] - Fun fact, Marius reportedly said this to Mithradates in real life too!

Share: