Chapter Fourty: The Best Lack All Conviction

Extract from Imperial Matters: Britain in the Early 20th Century

By Sir William Crowe, Published Oxford University Press 1955

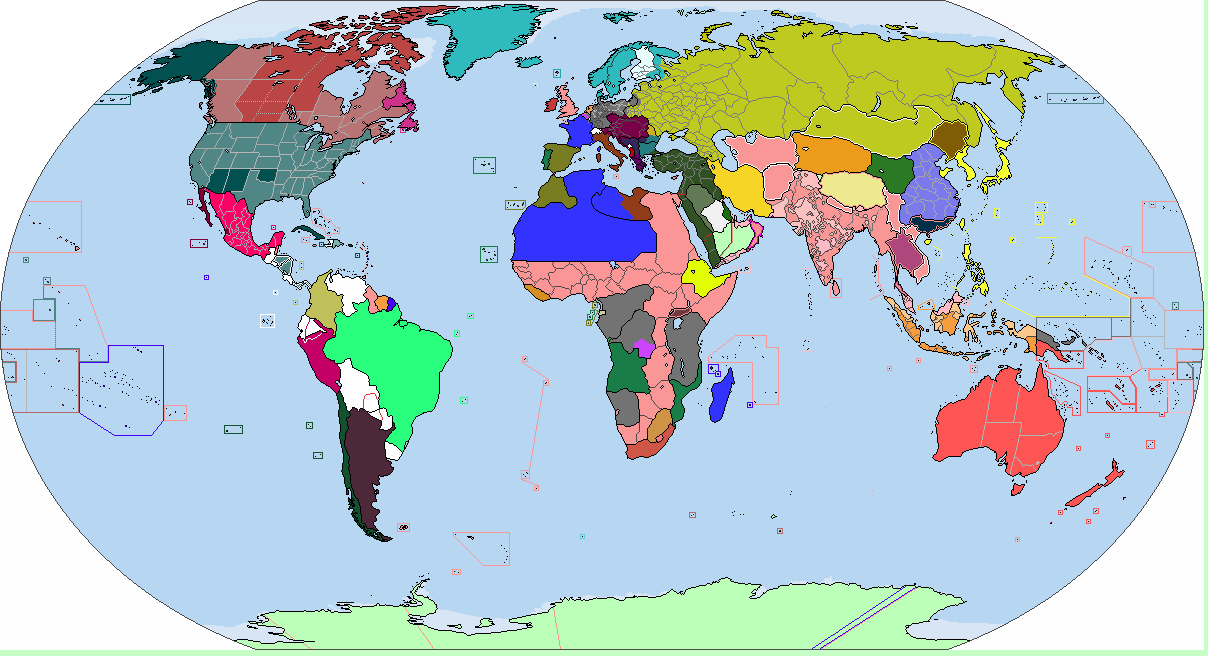

Lloyd George’s ministry was undoubtedly a moderate one, but made one majorly progressive change that would shape the world for years to come. The borders of Britain’s west African Colonies had been a point of contention to many and their drawing had been questioned regularly. Some wanted a more logical, easy to manage redrawing whilst others wished to maintain the tribal borders that had been achieved. Lloyd George reached a compromise. By working with Oyo, Hausa, and other tribes, the Liberal Government redrew the colonial borders with none of the straight line nonsense of the previous government and based new borders only on local allegiance. This allowed the British to work with and through local leaders more effectively and won a good deal of favour among the locals. The move is praised as one of Lloyd George’s best and created a stable environment within which Mr Gandhi's Charity, Global Progress, was able to expand its schooling programs, bolstered by another £1 million of funding from the British government and even more from private donors. As Britain’s Africa flourished, so too did her colonies across the Atlantic.

The Yoruba formed an essential part of Britain's West African Tribal Network

Newfoundland is undoubtedly something of an oddity within the British Empire. As the Australasians had absorbed even the distant New Zealanders and the Canadians rules as far as British Columbia, many expected the Newfoundlanders to fall in fast behind the rest of Britain’s North American colonies and attach themselves to the prosperous dominion. However in 1909, following a referendum planned a few years previously under Britain’s Imperial Socialist Government, the Colony declared its independence as an autonomous Dominion. The Commonwealth of Newfoundland held its first elections in the September of that year, its House of Assembly forming the single body legislature, and became the first British Territory to elect a Fabian Majority. The Newfoundlander Fabian Party (making official what had only been a nickname across the Atlantic) swept 26 of the 50 seats available and stood against only 19 Conservative, 3 liberal and 2 independents in opposition. The election was, in truth, mostly missed by the British and even Canadians, whose priorities were firmly fixed on the conflict in Europe but its importance should not be understated. The Fabian victory is largely due to their support for the prominent fishing industry, their promise to root out corruption and a devotion to democracy that allowed them to carry the working class vote. Of course though, much of the world was focused on other matters…

Extract from Austria's War

By Franz Berman, Published Hamburg University Press, 1989

The Austrian Silesian Offensive of late 1909 was meant to be one of those grand advances that was meant to be a death knell for the German Empire. It was very much not. The Austro-Hungarian Army had based much of its strategies of the last few decades on wars in the Balkans or perhaps against Russia, the Austro-German Split having one as a great shock. This lead to a general lack of preparedness among the Austrian High Command that would take a great deal of time to overcome. So it was that when General von Straussenburg came to make the invasion, he was doing so largely with strategies he developed on the fly. Nevertheless, his 220,000 men crossed into Northern Silesia on the 1st of October and were able to capture the region unopposed, supposing that the rest of the area would soon follow suit. There were very few German forces in the region and von Straussenburg made the rather erroneous decision to split his army into three, so that he could more rapidly gain a strong foothold, assuming that he would have a week at the very least for any meaningful response to come from the Germans. He was wrong. As a 77,000 strong contingent of the Austrian army marched south to recapture Southern Silesia and perhaps secure some territory within German-occupied Poland, they were quite surprised to come across the equally bemused German 8th Army. The Germans had been only recently deployed to the Southern Polish front and consisted in large part of raw recruits. They had, however, been ordered to reinforce Silesia some two weeks earlier, when the Austrian threat made itself known. This accidental confrontation would end in disaster for the Austrians as the full strength, 200,000 man German Army crushed the Austrian contingent and forced its surrender with only minimal casualties. The 8th made an immediate march North, to dislodge von Straussenburg and meet up with another German force coming in from the North. Von Straussenburg panicked and, in order to prevent himself and his armies being crushed between two superior forces he withdrew west into Austrian Bohemia. Germany was reluctant to risk an offensive into Austrian territory just yet and so relented, many Germans returning to the eastern front of Poland, where a minor Russian push was causing some difficulties. Von Straussenburg would spend the next month and a half assembling his army and finally struck again, this time through the south. When he met the German 8th Army a second time he outnumbered them almost 2:1 and was able to gain ground, however his inexperienced troops still had trouble forcing their way through the light trenches that the Germans had dug; an understocking of machine guns and artillery shells put the Habsburg forces heavily on the back foot.

Austrian Uniforms were still colourful when compared to those of their foes and caused issues throughout the war.

Elsewhere, the Austrians met with more success, though were forever hampered by general inexperience and inferior equipment. In Serbia, they met with age old foes who were distracted in the east, making quick and clear gains in the opening weeks of their invasion. However the Serbs rapidly pulled men west, allowing the Bulgarians to pick up the slack, this meant that by November the front had boiled to a the same slog the Austrians faced in the North. The Serbians also made extensive use of their own Skyfleet, scouting out Austrian positions in a way that simply could not be matched. The Serbs mirrored these techniques against the Greeks in the south and though the Greeks had focused primarily on the Albanians in their assault, their veteran army had made the very same advance less than a decade before and had little trouble pushing the Serbs back. Meanwhile the Bulgarians had been able to close off the Romanian front, preventing a collapse, and were dealing with the Ottomans as rapidly as they could. The Turks were still gaining ground at a breakneck pace but took casualties every step of the way.

In Italy, things were different indeed. The Austrians had made short work of Italian territory east of the Alps and the Italians, in turn, had done little to resist. The Austro-Hungarians found that their true challenge lay in the mountains themselves. Every single pass from Austria to Italy had been lined with more than 3 miles of trenches. The was the first wartime use of trenches on such a colossal scale and the Italians had completely blocked any Austrian strike into their homeland. The Battle of Ampezzo, a 430,000 man Austrian Army hoped to break the 190,000 strong Italian Fifth Army and push south into mainland Italy, knocking them out of the war completely. Within the first hour of the battle, the Austrians suffered more than 10,000 casualties, running directly into machine gun fire and artillery shelling. As the hours passed on the Austrians gave men every step of the way. It was later found that Austrian Artillery was not correcly calibrated and had been consistently missing the Italian positions. This meant that wave after wave of infantry had almost no effect on the Italians lines and only at nightfall were the Austrians able to claim a single line of the trenches. They had lost more than 100,000 men to claim this small area of land and took the chance to rest and recover. During the night, the Italians struck back. Having lost not even a tenth of what their foes had, the Italians struck with anger and skill. The Austrians had few machine guns and the fleeing Italians had made sure to destroy or bring with any machine guns they had control of. The Italian Counterattack swept into the trenches and dislodged the Austrians entirely. Habsburg forces went into full retreat and, with 120,000 men less than just two days before, left the alpine passes. Italy was safe, for now.

This Photo, taken before the Battle, shows Austrian Soldiers. All but one would die in the days to come.

On the Western Front, things continued to escalate. The final Great Movement of the Western War, the Race to the Sea, had begun. German-Dutch forces struck on October 13th, moving from positions in Western Holland they attempted to capture a chunk of Belgium and get around the Entente line, allowing for a massive flanking maneuver. The Franco-Belgians responded and in turn, moved west of the Bloc armies. This one upmanship continued for two weeks, minor advances and skirmishes on the edge of trench lines until eventually, on November 2nd, the German Third and Dutch First armies marched into Belgium, hugging the coast tightly, and captured Antwerp. A cutting blow for Belgian morale, this allowed the Dutch to fill in the gaps, so to speak, and dictate the front line of the war for years to come. Though the French were able to get minor tracts of land in the south, the Germans were the first to come to a grave realisation; this was to be a war of attrition and soon these lines would be set in stone. As November turned into December and December into January, 1910 dawned. By the turn of the new year little had changed, armies had dug in and awaited the spring offensives. Across Europe people were starting to realise how long this war would be.

The Speed of the German Advance led to their Victory in the Race to the Sea

One of the few events of the Winter of 1909 was the shooting at Thionville, an event that captured the true tragedy of the war. On Christmas Day, on both sides of the trenches, German and French forces heard each other singing the same carols, celebrating the same holiday and even shouting messages to each other. Before long people were poking out of the trenches and waving, the conflict of days before faded to the back of people’s minds. At midday, one boy, Oscar Dietrich, waved a little white flag in one hand and held a football in the other. Oscar made his way into the trenches and called, in his best French, for a game. His friends called him mad but within a few minutes a Frenchman joined young Oscar. The two shook hands and it seemed as if peace might reign for one day. It would not. Angered by this seeming defection, French Colonel Michael Vellon climbed out of his trench, pistol in hand, and shot the pair of them. The Germans, outraged, immediately returned fire and though one or two Frenchmen bordered on defection after the betrayal from their commander, before long they too were forced to return to battle. The War was destructive and it would consume all.

Extract from Imperial Matters: Britain in the Early 20th Century

By Sir William Crowe, Published Oxford University Press 1955

Lloyd George’s ministry was undoubtedly a moderate one, but made one majorly progressive change that would shape the world for years to come. The borders of Britain’s west African Colonies had been a point of contention to many and their drawing had been questioned regularly. Some wanted a more logical, easy to manage redrawing whilst others wished to maintain the tribal borders that had been achieved. Lloyd George reached a compromise. By working with Oyo, Hausa, and other tribes, the Liberal Government redrew the colonial borders with none of the straight line nonsense of the previous government and based new borders only on local allegiance. This allowed the British to work with and through local leaders more effectively and won a good deal of favour among the locals. The move is praised as one of Lloyd George’s best and created a stable environment within which Mr Gandhi's Charity, Global Progress, was able to expand its schooling programs, bolstered by another £1 million of funding from the British government and even more from private donors. As Britain’s Africa flourished, so too did her colonies across the Atlantic.

The Yoruba formed an essential part of Britain's West African Tribal Network

Newfoundland is undoubtedly something of an oddity within the British Empire. As the Australasians had absorbed even the distant New Zealanders and the Canadians rules as far as British Columbia, many expected the Newfoundlanders to fall in fast behind the rest of Britain’s North American colonies and attach themselves to the prosperous dominion. However in 1909, following a referendum planned a few years previously under Britain’s Imperial Socialist Government, the Colony declared its independence as an autonomous Dominion. The Commonwealth of Newfoundland held its first elections in the September of that year, its House of Assembly forming the single body legislature, and became the first British Territory to elect a Fabian Majority. The Newfoundlander Fabian Party (making official what had only been a nickname across the Atlantic) swept 26 of the 50 seats available and stood against only 19 Conservative, 3 liberal and 2 independents in opposition. The election was, in truth, mostly missed by the British and even Canadians, whose priorities were firmly fixed on the conflict in Europe but its importance should not be understated. The Fabian victory is largely due to their support for the prominent fishing industry, their promise to root out corruption and a devotion to democracy that allowed them to carry the working class vote. Of course though, much of the world was focused on other matters…

Extract from Austria's War

By Franz Berman, Published Hamburg University Press, 1989

The Austrian Silesian Offensive of late 1909 was meant to be one of those grand advances that was meant to be a death knell for the German Empire. It was very much not. The Austro-Hungarian Army had based much of its strategies of the last few decades on wars in the Balkans or perhaps against Russia, the Austro-German Split having one as a great shock. This lead to a general lack of preparedness among the Austrian High Command that would take a great deal of time to overcome. So it was that when General von Straussenburg came to make the invasion, he was doing so largely with strategies he developed on the fly. Nevertheless, his 220,000 men crossed into Northern Silesia on the 1st of October and were able to capture the region unopposed, supposing that the rest of the area would soon follow suit. There were very few German forces in the region and von Straussenburg made the rather erroneous decision to split his army into three, so that he could more rapidly gain a strong foothold, assuming that he would have a week at the very least for any meaningful response to come from the Germans. He was wrong. As a 77,000 strong contingent of the Austrian army marched south to recapture Southern Silesia and perhaps secure some territory within German-occupied Poland, they were quite surprised to come across the equally bemused German 8th Army. The Germans had been only recently deployed to the Southern Polish front and consisted in large part of raw recruits. They had, however, been ordered to reinforce Silesia some two weeks earlier, when the Austrian threat made itself known. This accidental confrontation would end in disaster for the Austrians as the full strength, 200,000 man German Army crushed the Austrian contingent and forced its surrender with only minimal casualties. The 8th made an immediate march North, to dislodge von Straussenburg and meet up with another German force coming in from the North. Von Straussenburg panicked and, in order to prevent himself and his armies being crushed between two superior forces he withdrew west into Austrian Bohemia. Germany was reluctant to risk an offensive into Austrian territory just yet and so relented, many Germans returning to the eastern front of Poland, where a minor Russian push was causing some difficulties. Von Straussenburg would spend the next month and a half assembling his army and finally struck again, this time through the south. When he met the German 8th Army a second time he outnumbered them almost 2:1 and was able to gain ground, however his inexperienced troops still had trouble forcing their way through the light trenches that the Germans had dug; an understocking of machine guns and artillery shells put the Habsburg forces heavily on the back foot.

Austrian Uniforms were still colourful when compared to those of their foes and caused issues throughout the war.

Elsewhere, the Austrians met with more success, though were forever hampered by general inexperience and inferior equipment. In Serbia, they met with age old foes who were distracted in the east, making quick and clear gains in the opening weeks of their invasion. However the Serbs rapidly pulled men west, allowing the Bulgarians to pick up the slack, this meant that by November the front had boiled to a the same slog the Austrians faced in the North. The Serbians also made extensive use of their own Skyfleet, scouting out Austrian positions in a way that simply could not be matched. The Serbs mirrored these techniques against the Greeks in the south and though the Greeks had focused primarily on the Albanians in their assault, their veteran army had made the very same advance less than a decade before and had little trouble pushing the Serbs back. Meanwhile the Bulgarians had been able to close off the Romanian front, preventing a collapse, and were dealing with the Ottomans as rapidly as they could. The Turks were still gaining ground at a breakneck pace but took casualties every step of the way.

In Italy, things were different indeed. The Austrians had made short work of Italian territory east of the Alps and the Italians, in turn, had done little to resist. The Austro-Hungarians found that their true challenge lay in the mountains themselves. Every single pass from Austria to Italy had been lined with more than 3 miles of trenches. The was the first wartime use of trenches on such a colossal scale and the Italians had completely blocked any Austrian strike into their homeland. The Battle of Ampezzo, a 430,000 man Austrian Army hoped to break the 190,000 strong Italian Fifth Army and push south into mainland Italy, knocking them out of the war completely. Within the first hour of the battle, the Austrians suffered more than 10,000 casualties, running directly into machine gun fire and artillery shelling. As the hours passed on the Austrians gave men every step of the way. It was later found that Austrian Artillery was not correcly calibrated and had been consistently missing the Italian positions. This meant that wave after wave of infantry had almost no effect on the Italians lines and only at nightfall were the Austrians able to claim a single line of the trenches. They had lost more than 100,000 men to claim this small area of land and took the chance to rest and recover. During the night, the Italians struck back. Having lost not even a tenth of what their foes had, the Italians struck with anger and skill. The Austrians had few machine guns and the fleeing Italians had made sure to destroy or bring with any machine guns they had control of. The Italian Counterattack swept into the trenches and dislodged the Austrians entirely. Habsburg forces went into full retreat and, with 120,000 men less than just two days before, left the alpine passes. Italy was safe, for now.

This Photo, taken before the Battle, shows Austrian Soldiers. All but one would die in the days to come.

On the Western Front, things continued to escalate. The final Great Movement of the Western War, the Race to the Sea, had begun. German-Dutch forces struck on October 13th, moving from positions in Western Holland they attempted to capture a chunk of Belgium and get around the Entente line, allowing for a massive flanking maneuver. The Franco-Belgians responded and in turn, moved west of the Bloc armies. This one upmanship continued for two weeks, minor advances and skirmishes on the edge of trench lines until eventually, on November 2nd, the German Third and Dutch First armies marched into Belgium, hugging the coast tightly, and captured Antwerp. A cutting blow for Belgian morale, this allowed the Dutch to fill in the gaps, so to speak, and dictate the front line of the war for years to come. Though the French were able to get minor tracts of land in the south, the Germans were the first to come to a grave realisation; this was to be a war of attrition and soon these lines would be set in stone. As November turned into December and December into January, 1910 dawned. By the turn of the new year little had changed, armies had dug in and awaited the spring offensives. Across Europe people were starting to realise how long this war would be.

The Speed of the German Advance led to their Victory in the Race to the Sea