Olof Palme had fought his seventh election campaign in 1988, and while he was still a sharp politician - indeed, he won the election - some observators noted that he seemed more tired than usual during the campaign and expected that he would designate a successor and retire before the election. As expected, Palme did resign, but it was announced unexpectedly early, already in May the year after the election. Most people who speculated, and many did, expected Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Industry Ingvar Carlsson to be anointed but he ruled out the scenario with gusto immediately after Palme resigned. Carlsson would reveal several years in his memoirs that he declined when Palme asked him to succeed him as he didn't see himself as a potential Prime Minister. Following Social Democratic tradition, no one ever declared their interest in the party leadership until the nominating committee decided on a candidate, but several members of Palme's cabinet were rumored to be interested in succeeding him. In the end, Minister for Finance Kjell-Olof Feldt was elected leader despite internal protests from the party's more ideological members, that were only placated by a careful allocating of cabinet posts to make it "left-wing enough".

One month and one day after Kjell-Olof Feldt was inaugurated as party leader and Sweden's new Prime Minister, the real estate company

Nyckeln collapsed, setting the stage for a new episode in Swedish history - the crisis years.

Adelsohn's government had introduced relatively radical deregulation policies, including removing several limits on money lending and a more generous tax deduction for home mortgage interest. This would create a major housing bubble - indeed, students quit school early in droves during the late 80's to work in the construction industry - which burst with the collapse of

Nyckeln, bringing several other real estate companies as well as a few banks down to their knees. The coming years would be completely defined by the crisis and the government's response to it, which except for a couple of costly bank bailouts consisted of sticking to the rules of fiscal conservatism and presenting big and painful spending cuts that were deemed necessary to save the economy. Many of those who had not lost money or jobs through the financial collapse had to leave the public sector as its costs were rationalized. Many of these cuts had to be realized with the help of the centre-right parties, especially the People's Party, as the Left-Communists refused to support the government's "anti-worker" measures.

The cuts were not without controversy within the Social Democrats either, however. Feldt was never popular among a large segment of the party and especially its affiliated unions, and when Minister for Health Care Bo Holmberg resigned citing "fundamental differences with the Prime Minister on critical issues" in late 1990 the party essentially entered a civil war with several leading politicians demanding Feldt's resignation and a party leader who would not implement "neo-liberal Moderate policies". Feldt refused to resign citing the need for "strong leadership" and the Centre and People's Parties pledged to not support a motion of no confidence introduced by the Left-Communists to bring down the government or its Minister for Finance Erik Åsbrink in the name of keeping the country stable in tough times. In response, several Social Democrats declared that they would stand as an independent list in the 1991 election as a Social Democratic anti-austerity vehicle which would rejoin the party only upon Feldt's resignation and the party "recommitting to Social Democratic ideals". Several MPs defected to this new list, dubbed the "Workers' Union List for a new Social Democracy"

(Arbetarnas förbundslista för en ny socialdemokrati) and was headed by the chair of the Swedish Trade Union Confederation himself, Stig Malm, as well as Bo Holmberg and former Minister for Comunications Roine Carlsson along with other trade union bosses and defected MPs.

Unity among the right-wing parties was not much higher. After polls had shown the People's Party as the largest right-wing party during most of 1988, Adelsohn's Moderates were determined to win back voters by swiping as much at the People's Party as they attacked the government. The Moderates embraced its status as the most right-wing party in the Riksdag and attempted to rally the base by decrying especially the People's Party as all but traitors to the non-socialist cause by co-operating with the Social Democrats to combat the crisis and sticking to the "wishy-washy" and evidently failed policies of the old pre-crisis times. The Moderates instead presented their own policies, more radical and at times even populist, as strange as it would seem - the party's tax policies were simplified and could easily be used in zingers. Adelsohn himself did all he could to advocate a future "New Swedish Spring" of neoliberal policies that would begin when the crisis had been defeated by improving the business climate. He also competed with the People's Party in being the most pro-Europe party in the wake of the crisis and the events in the former East Bloc after the Berlin Wall fell in the fall of 1989, even as Sweden under Feldt applied for membership in the EC. Adelsohn did so while promising to advocate for limits and exceptions to the European Common Market to not threaten domestic jobs and also promised that immigration would be severely restricted as to not hurt Swedish jobs in the time of crisis, an argument which at times was presented with touches of nationalism and even resemblances of racism (or at least racial insensitivity, which Adelsohn was known for).

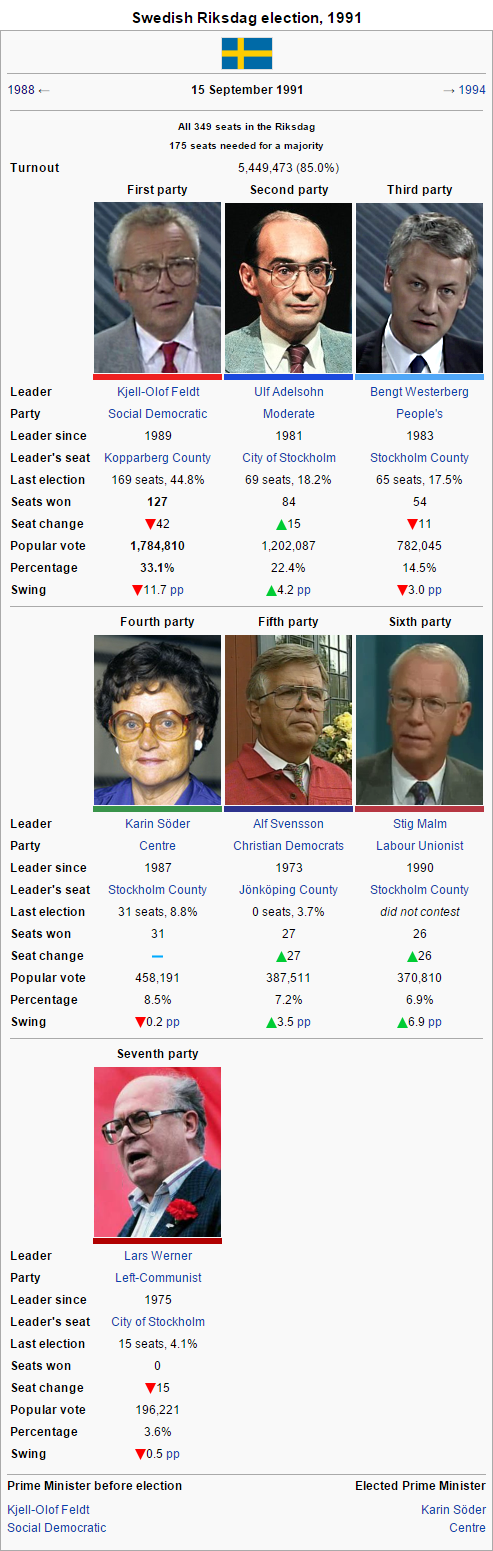

The people were hungry for populism in the wake of the crisis, and Adelsohn's strategy was thus successful, succeeding in capturing some of this sentiment. The Christian Democrats who spoke of values and family also became a popular voice among voters who felt unsafe and uneasy in the new reality. They along with the Workers' Union were the big benefactors of the crisis, the latter two entering the Riksdag with 7.2% (mostly taken from right-wing voters) and 6.9% of the vote (mostly Social Democrats but also surprisingly many Communists) respectively. The People's Party was hurt badly by the attacks from the Moderates but retained many voters who were alienated by Adelsohn's radicalism and who had started to identify with the party and Westerberg after voting for it twice. The Centre Party mostly stayed under the radar of Adelsohn's major attacks and while it lost a few voters to death and Adelsohn's populism it also gained some right-wing voters who preferred Karin Söder to the confrontative Westerberg and Adelsohn, although most of them voted for the Christian Democrats.

The big losers of the election were the Left-Communists, who were overshadowed by the Workers' Union and lost much credibility upon the fall of the Soviet Union. The party tried to campaign on the rights of women, immigrants and other minorities as well as the environment and workers' rights, but ended up short of 4% and were forced out of the Riksdag, having lost many (especially male) voters to the Workers' Union. The big focus on the economy also hurt the Greens, who gained a few protest votes but far from enough to enter the Riksdag (they ended up at 3.1%). Some leftist commentators called for the saner members of the Left-Communists to abandon the sunken ship and join with the Workers' Union to form a new party (despite the latter staying with their pledge to rejoin a Social Democratic Party that ended austerity, but the Communists' social justice emphasis meant bad relations with the male-dominated Workers' Union led by the chauvinist Malm (who once called the Social Democratic Women's League "a flock of c*nts" while in a taxi) and Left-Communist deputy party leader Gudrun Schyman told journalists that she would "rather die than be in the same party as Stig Malm".

With all votes counted, the Social Democrats had a historically low result on their hands with only 33.1% of the vote. They were far from commanding a majority even with the aid of the 26 MPs from the Workers' Union. Ulf Adelsohn's party was the largest right-wing one, but the Moderate campaign had destroyed the relations with the other right-wing parties and especially the People's Party. Bengt Westerberg declared that he would not join a coalition with the Moderates or support Adelsohn as Prime Minister again - mostly due to a desire for becoming Prime Minister himself, most people rightly speculated. Adelsohn expected to be shut out and prepared to absorb disgruntled centre-right voters in the future but also refused to let his bitter rival Westerberg become Prime Minister, hoping to force the election of another Liberal leader. In the end, the Christian Democrats solved the problem by proposing that Karin Söder of the Centre Party would be a compromise candidate. Adelsohn and Westerberg had to accept - the alternative of a coalition with the Social Democrats was not feasible for the centre-right with a clear right-wing majority in the Riksdag and all of them knew that a snap election would tarnish the right-wing parties for a generation - and Karin Söder would thus become Sweden's first woman Prime Minister, commanding "the Western world's least stable government" with pundits soon predicting how quickly it would fall.