yboxman

Banned

#1:The Fall

The year is 1356 and All Under Heaven Is Great Chaos. For 450 years a succession of Barbarian Nomadic people, first the Khitans, then the Jurchens, finally the Mongols, have encroached upon the Middle kingdom, carving out states in the North. In those states the traditional (1) leading role of the Confucian scholar gentry has been curtailed, overlain by a foreign military caste.

For unlike previous invaders, the more recent hordes have maintained control of their Steppe homeland, and have taken great pains to retain a separate identity and organization placing them above the conquered Han (2).

The last wave of conquerors, not content to rule over the plains of Northern China, have crushed the Song remnant over half a century of near constant warfare, and occupied the river valleys and hills of the south. Under Kublai Khan they have proclaimed themselves of the Yuan dynasty, and for a century have ruled over the largest empire, Chinese or otherwise, the world has ever known. Elsewhere, their Kin have swept across the entirety of Inner Asia, conquered the Muslim states of the Middle East, and ravaged and made tributaries of the East Slav principalities.

But now the Yuan dynasty has crumbled into infighting and the Han have had enough. Swept up by the messianical fervor of the prophecy of the coming Maitreya Budha, The Han stand united against their opressors!

Well… actually, not so much.

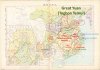

Map is somewhat misleading, as the southern Red turbans are not broken up yet, but it's the best representation of a confused situation I could find. Shaanxi and Henan held by Mongol warlords only nominally loyal to the Yuan court in Dadu, Northern Red turbans split between main, Song faction led by LIU FUTONG (刘福通) with Han Lin’er as figurehead and other regimes in Shandong and . Southern Red turbans still nominally "united" in empire of Tianwan under Xu Shouhui 徐壽輝. The split into Ming under ZHU YUANZHANG (朱元璋), Dahan under CHEN YOULIANG (陈友谅), and Daxia under MING YUZHEN (明玉珍) is already in the works though. FANG GUOZHEN (方国珍) is playing merry pirate in Fukien, and ZHANG SHICHENG (张士诚) has proclaimed the kingdom of Dazhhou in Jiangsu. Interesting times.

The initial outbreak of the Red turban rebellion in the Yellow river valley has suffered reverses at the hands of the Yuan and various Mongol warlords, splintering into three components. The rebel states of Yidu in the Shandong peninsula, and of Jin in the Liaodong peninsula are nominally subordinate to the self proclaimed latter Song dynasty in Anhui. This dynasty is officially ruled by Han Lnier, Son of the slain rebel and prophet Hong Shantong, but is effectively led by his former subordinate Liu Futong.

The situation of the Northern Red turbans would be desperate were it not for two things. First, the Yuan are just as divided and fractious. The Mongol warlord Koke Temur rules Henan and owns only nominal Alleigence to the fractious Yuan court in Dadu. Indeed, he might very well prefer to march on the capital and displace the current ineffectual emperor if only the Red Turbans would permit him. Bolad Temur, in Shaanxi, has few such inhibitions and is maneuvering for the time in which he might make his move.

Second, the northern rebellion sparked a copy-cat rebellion by the southern adherents of the same Millenarian sect following their own leaders and dogmatic prophecies. From his base in Hannyang Xu Shouhui has proclaimed the Tianwan empire and dominates the upper and middle Yangtze valley. Or rather, his fractious and nominal subordinates do. Chen Youliang, in addition to controlling his own base in Jiangzhou, rules Tianwan in all but name. He has rivals, however.

To the West, Ming Yuzhen , an adherent of Manichienism, is encroaching into Sichuan, vanquishing the weak Yuan and local forces in his path. To the east, Zhu Yuanzhang, a late-comer to the Red Turban movement who has joined his force to the insurgency (3) has just conquered Nanking and is busy establishing his own power base.

South of the Yangtze Valley, southern China is a maze of warlord fiefs, some are ruled by Han, others by Mongols. Some have proclaimed their own regimes, while others retain nominal subordination to the distant Yuan court. Of the latter, the foremost is the Principality of Lang in the far southwest, ruled by the Mongol prince Basalawarmi. In Fukien, Chen Youding, a Han commander loyal to the Yuan dynasty is batteling the Ispah rebels, an ecelectic coalition of Arab, Persian and native Chinese Muslims led by Saif ad-Din (赛甫丁) and Amir ad-Din (阿迷里丁). Fang Guozhen, who has the dubious honor of having launched the wave of rebellion against against Mongol rule in the 1340s dominates coastal Zhiejiang and every coast his fleet of pirates raids. No religious fanatic, he began his career by fleeing unjust accusations of outlawery. Naturally, he then proceeded to gather outlaws arounf him into a deadly pirate fleet with which the depleted navy of Yuan has proved unable to contend.

Since then he had alternately accepted bribes and official positions from the Yuan to end his raiding (4) and returned to his merry pirating ways. North of him is another opportunistic warlord. Unassuming and indolent Zhang Shicheng dominates Jiangsu and the Ynagtze delta, the richest and most advanced part of China, whose grain harvest regularly feeds the Yuan capital of Dadu. Or it did before Zhang cut off the Grand Canal. A salt trader in his origins, and with three capable and loyal brothers, Zhang stands out amongst the radical lower class warlords and rebels in having proven capable of attracting gentry and merchants to support his regime and Confucian scholars to serve as administrators.

Two years ago he felt sufficiently well established to proclaim himself king Tianyou (天佑) of Dazhou and his territory has greatly expanded since then. Now, however, ge is now facing the first serious Challenge to his regime. Where before he has been operating in the power vaccum of the collapsing Yuan and has been able to co-opt smaller rebel bands, the capture Nanking by the southern Red turbans under Zhu Yuanzhang (5), force him to firmly establish his Western Frontiers. Perhaps he can even take Nanking himself now that it's fortifications are breached!

It is as he rides in front of his gathered forces, prepared to lead them to for the greater glory of the kingdom of Dazhou, that his horse slips. Horrified, his brother Zhang Shide (张士德) dismounts and rushes towards him. It is no good, king Tianyou (天佑) of Dazhou is dead (6).

(1) Hmmm… Well, traditional under the Song. Tradition is usually another word for entrenched privilege, regardless of how old it actually is.

(2) "Every conqueror of China has inevitably been assimilated by it" my ass.

(3) Well, actually his father in law and commander did. But this is getting confusing enough as it is.

(4) His most recent appointment if supervisor of Grain transport. The bright Idea was that if he was supervising, and taxing, the transports to Dadu he wouldn’t raid them.

(5) Their seems to be some disagreement in sources as to whether Zhu Yuanzhang was a (nominal) follower of the Southern or Northern Red turbans. My take is that he switched his alleigence to han Lni'er only after Chen offed Xu Shouhui.

(6) And this is the POD. OTL it is Zhang Shide, one of the most capable and aggressive generals of this era, who fell off his horse, albeit a decade later, when Zhu Yuanzhang was moving in for the kill.

The year is 1356 and All Under Heaven Is Great Chaos. For 450 years a succession of Barbarian Nomadic people, first the Khitans, then the Jurchens, finally the Mongols, have encroached upon the Middle kingdom, carving out states in the North. In those states the traditional (1) leading role of the Confucian scholar gentry has been curtailed, overlain by a foreign military caste.

For unlike previous invaders, the more recent hordes have maintained control of their Steppe homeland, and have taken great pains to retain a separate identity and organization placing them above the conquered Han (2).

The last wave of conquerors, not content to rule over the plains of Northern China, have crushed the Song remnant over half a century of near constant warfare, and occupied the river valleys and hills of the south. Under Kublai Khan they have proclaimed themselves of the Yuan dynasty, and for a century have ruled over the largest empire, Chinese or otherwise, the world has ever known. Elsewhere, their Kin have swept across the entirety of Inner Asia, conquered the Muslim states of the Middle East, and ravaged and made tributaries of the East Slav principalities.

But now the Yuan dynasty has crumbled into infighting and the Han have had enough. Swept up by the messianical fervor of the prophecy of the coming Maitreya Budha, The Han stand united against their opressors!

Well… actually, not so much.

Map is somewhat misleading, as the southern Red turbans are not broken up yet, but it's the best representation of a confused situation I could find. Shaanxi and Henan held by Mongol warlords only nominally loyal to the Yuan court in Dadu, Northern Red turbans split between main, Song faction led by LIU FUTONG (刘福通) with Han Lin’er as figurehead and other regimes in Shandong and . Southern Red turbans still nominally "united" in empire of Tianwan under Xu Shouhui 徐壽輝. The split into Ming under ZHU YUANZHANG (朱元璋), Dahan under CHEN YOULIANG (陈友谅), and Daxia under MING YUZHEN (明玉珍) is already in the works though. FANG GUOZHEN (方国珍) is playing merry pirate in Fukien, and ZHANG SHICHENG (张士诚) has proclaimed the kingdom of Dazhhou in Jiangsu. Interesting times.

The initial outbreak of the Red turban rebellion in the Yellow river valley has suffered reverses at the hands of the Yuan and various Mongol warlords, splintering into three components. The rebel states of Yidu in the Shandong peninsula, and of Jin in the Liaodong peninsula are nominally subordinate to the self proclaimed latter Song dynasty in Anhui. This dynasty is officially ruled by Han Lnier, Son of the slain rebel and prophet Hong Shantong, but is effectively led by his former subordinate Liu Futong.

The situation of the Northern Red turbans would be desperate were it not for two things. First, the Yuan are just as divided and fractious. The Mongol warlord Koke Temur rules Henan and owns only nominal Alleigence to the fractious Yuan court in Dadu. Indeed, he might very well prefer to march on the capital and displace the current ineffectual emperor if only the Red Turbans would permit him. Bolad Temur, in Shaanxi, has few such inhibitions and is maneuvering for the time in which he might make his move.

Second, the northern rebellion sparked a copy-cat rebellion by the southern adherents of the same Millenarian sect following their own leaders and dogmatic prophecies. From his base in Hannyang Xu Shouhui has proclaimed the Tianwan empire and dominates the upper and middle Yangtze valley. Or rather, his fractious and nominal subordinates do. Chen Youliang, in addition to controlling his own base in Jiangzhou, rules Tianwan in all but name. He has rivals, however.

To the West, Ming Yuzhen , an adherent of Manichienism, is encroaching into Sichuan, vanquishing the weak Yuan and local forces in his path. To the east, Zhu Yuanzhang, a late-comer to the Red Turban movement who has joined his force to the insurgency (3) has just conquered Nanking and is busy establishing his own power base.

South of the Yangtze Valley, southern China is a maze of warlord fiefs, some are ruled by Han, others by Mongols. Some have proclaimed their own regimes, while others retain nominal subordination to the distant Yuan court. Of the latter, the foremost is the Principality of Lang in the far southwest, ruled by the Mongol prince Basalawarmi. In Fukien, Chen Youding, a Han commander loyal to the Yuan dynasty is batteling the Ispah rebels, an ecelectic coalition of Arab, Persian and native Chinese Muslims led by Saif ad-Din (赛甫丁) and Amir ad-Din (阿迷里丁). Fang Guozhen, who has the dubious honor of having launched the wave of rebellion against against Mongol rule in the 1340s dominates coastal Zhiejiang and every coast his fleet of pirates raids. No religious fanatic, he began his career by fleeing unjust accusations of outlawery. Naturally, he then proceeded to gather outlaws arounf him into a deadly pirate fleet with which the depleted navy of Yuan has proved unable to contend.

Since then he had alternately accepted bribes and official positions from the Yuan to end his raiding (4) and returned to his merry pirating ways. North of him is another opportunistic warlord. Unassuming and indolent Zhang Shicheng dominates Jiangsu and the Ynagtze delta, the richest and most advanced part of China, whose grain harvest regularly feeds the Yuan capital of Dadu. Or it did before Zhang cut off the Grand Canal. A salt trader in his origins, and with three capable and loyal brothers, Zhang stands out amongst the radical lower class warlords and rebels in having proven capable of attracting gentry and merchants to support his regime and Confucian scholars to serve as administrators.

Two years ago he felt sufficiently well established to proclaim himself king Tianyou (天佑) of Dazhou and his territory has greatly expanded since then. Now, however, ge is now facing the first serious Challenge to his regime. Where before he has been operating in the power vaccum of the collapsing Yuan and has been able to co-opt smaller rebel bands, the capture Nanking by the southern Red turbans under Zhu Yuanzhang (5), force him to firmly establish his Western Frontiers. Perhaps he can even take Nanking himself now that it's fortifications are breached!

It is as he rides in front of his gathered forces, prepared to lead them to for the greater glory of the kingdom of Dazhou, that his horse slips. Horrified, his brother Zhang Shide (张士德) dismounts and rushes towards him. It is no good, king Tianyou (天佑) of Dazhou is dead (6).

(1) Hmmm… Well, traditional under the Song. Tradition is usually another word for entrenched privilege, regardless of how old it actually is.

(2) "Every conqueror of China has inevitably been assimilated by it" my ass.

(3) Well, actually his father in law and commander did. But this is getting confusing enough as it is.

(4) His most recent appointment if supervisor of Grain transport. The bright Idea was that if he was supervising, and taxing, the transports to Dadu he wouldn’t raid them.

(5) Their seems to be some disagreement in sources as to whether Zhu Yuanzhang was a (nominal) follower of the Southern or Northern Red turbans. My take is that he switched his alleigence to han Lni'er only after Chen offed Xu Shouhui.

(6) And this is the POD. OTL it is Zhang Shide, one of the most capable and aggressive generals of this era, who fell off his horse, albeit a decade later, when Zhu Yuanzhang was moving in for the kill.